Clouds and Light

“I’m not painting cows, but the effects of light.” A surprising statement for Dutch artist Willem Maris and for Dutch art in general, with its great tradition of cow pictures. Why, in the mid-nineteenth century, would an artist in the Netherlands suddenly embrace light as his primary motif?

The exhibition Clouds and Light: Impressionism in Holland answers this and other questions. But first, to set the stage: in order to paint light, especially sunlight, Maris and his fellow artists had to spend a lot of time outdoors, under the open sky.

As early as 1863, nineteen-year-old Willem Maris, one of three painter brothers, created what is probably his most famous image of light on cows, Calves at a Trough. More than thirty years later, he painted Summer, a mature work marked by even greater luminosity.

The cow is there for the light, gliding over and past the animal—the light is not there for the cow.

Willem Maris: Summer, 1897, Dordrechts Museum, loan from Van Bilderbeek collection, 1951

The main motif is not the animals, but the light and the sky.

The exhibition Clouds and Light explores the development of Impressionism in Holland from 1850 to 1920. Here for the first time, audiences in Germany can experience a comprehensive view of this second great age of Dutch painting after the seventeenth century.

The exhibition traces the development of Dutch plein air painting—from its beginnings in the forest to the cloudy, silvery-gray light of the Hague School, the shimmering hues of urban Amsterdam Impressionism, and the expressive color of the movement known as Luminism.

Plein air painting in the forest

Boat, beach, water, clouds, seagulls: all in shimmering tones of gray

Urban everyday life, impressionistic.

Mill motifs and love of the homeland.

Impressionism in Holland features more than a hundred paintings by thirty-nine artists. Most are little known in Germany, since their work has not been collected by German museums.

The exhibition also sheds light on why windmills appear so often in Dutch art, and extends its view even into the modern period. Vincent van Gogh wasn’t the only artist in the Netherlands to be inspired, though in his own unique way, by the innovations of Impressionism. The new movement also shaped the work of another of the most famous artists in the world: the Amersfoort native Piet Mondrian.

Gerard Bilders: Pond in the Woods at Sunset, ca. 1862, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Nachlass J.B.A.M. Westerwoudt, Haarlem

The new developments in Dutch painting begin under the open sky. In the forest of Oosterbeek near Arnhem, a new artists’ colony has formed—just as in the French forest of Fontainebleau near Barbizon, where Camille Corot and many others are rediscovering nature. Later, the Oosterbeek artists will be joined by painters of the so-called Hague School such as Willem Roelofs and Jacob Maris. For the time being, they remain in the Netherlands.

One of the first painters in Oosterbeek to work outdoors is Johannes Bilders. His atmospheric, realistic scenes of ponds and trees, inspired by the seventeenth-century master Jacob van Ruisdael, set a new standard.

Johannes Warnardus Bilders: The Pond at Oosterbeek, 1831-1890, Groninger Museum / Photo: Marten de Leeuw

In the spirit of this new directness, Bilders’s twenty-three-year-old son Gerard, who is also an artist, observes:

Once one has resolved to become a landscape painter, one must live as much as possible out of doors, eat and drink, read and sleep beneath the trees and in the grass.

He’s right: the new open-air painting—plein air in French—no longer focuses on idealized compositions in which the landscape serves as a backdrop for mythical or biblical subjects. Instead, artists want to show what is really there: light and shadow, trees and streams, plants and animals.

Willem Roelofs: The Rainbow, 1875, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, gift of the Friends of Kunstmuseum Den Haag

Willem Roelofs’s rainbow spans a threateningly gloomy, cloud-filled sky—an unusual phenomenon of weather and light that rarely appears in Dutch painting.

Human figures are almost irrelevant in this Dutch exploration of open-air painting, which also influences later artists of the Hague School. From the 1840s onward, Johannes Bilders is joined in Oosterbeek by a throng of other artists including Willem Roelofs, Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël, Anton Mauve, and the Maris brothers Jacob, Matthijs, and Willem. In 1866, art collector Hendrik Willem Mesdag and his wife Sientje Mesdag-van Houten also arrive and begin training as artists.

Painting box of Camille Corot, bought after his death by Matthijs Maris, Kunstmuseum Den Haag

After the death of Camille Corot, Matthijs Maris purchases Corot’s paint box.

The new realism goes hand in hand with a new mobility. The advent of manufactured paint in tubes from 1840 on keeps artists’ pigments from drying out, and they can now go out into the landscape with a box of paints and brushes and a portable easel. Working on location, they find motifs that are deeply felt and touching, but also ordinary and unassuming. They convey a mood, or stemming in Dutch: an intimate experience of nature, embedded in the landscape.

Vincent van Gogh: Edge of a Wood, 1883, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo / Photo: Rik Klein Gotink

More modern than almost anyone else: Van Gogh is and remains the epitome of the avant-garde painter.

The Dutch forest landscape will flourish again in Van Gogh’s work of the 1880s and that of Jan Sluijters and Mondrian in the twentieth century. During the heyday of the Hague School, however, the focus shifts—to the broad expanse of the flat Dutch landscape.

Around 1870, many landscape painters move to The Hague, where a productive environment develops with a thriving art trade and artists’ organizations. The nearby coastline of the North Sea becomes a popular motif, as do the green polders— the flat land beyond the dikes. Meadows and cows, canals and windmills embody national pride in the everyday landscape of Holland.

Johan Barthold Jongkind: Ansicht von Delft, 1844, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague

Sky and light are the great sorcerers. The sky defines the painting. Painters can never look at the sky enough.

The mysterious darkness and the bluish, almost blackish green of the forest disappear from the paintings of the Hague School.

While images of the woods had been dominated by tree trunks and the forest floor—a genre known appropriately enough as sous-bois, or “undergrowth”—the paintings of the Hague School are generally marked by a low horizon, little ground, and a tall sky.

The artists of the Hague School capture the silvery-gray light of their northern homeland, creating a very different effect than the brilliant color of the French Impressionists. Among contemporaries, the Hague School is also known as the “Gray School” and is celebrated for its “poetry of gray.”

Jacob Maris: Vegetable Gardens near The Hague, um 1878, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague

An icon of the Hague School: cloudy winter sky over garden plots near The Hague.

The sky occupies nearly two thirds of the composition. The blanket of clouds culminates in shades of dark gray; the mood is hazy, misty, wet, and cold. There are kitchen gardens—and very little else. A painting could hardly be less spectacular. In comparison, Maris’s image of a fishing boat, while also very simple, seems to swarm with activity.

Jacob Maris: Fishing Boat, Kunstmuseum Den Haag

Boat, beach, water, clouds, seagulls: all in shimmering tones of gray

This picture, too, is a perfect example of why such artists were known as the “Gray School.” It also demonstrates why the Dutch painting of these years can be described as Impressionist: the scene is bathed in silvery light. The water and sand serve as a mirror, reflecting the silhouette of the ship and the gray of the sky, intensifying their luminosity.

The painters of the Hague School show little interest in the signs of emerging industrialization, such as railroads, factories, smokestacks, steamships, and telegraph lines. They also ignore the rapid expansion of the cities: between 1850 and 1900, the population of The Hague grew from 70,000 to 200,000 inhabitants.

Yet a handful of works do include features of the new industrial age. Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch’s View of Haarlem shows factory smokestacks with plumes of smoke, as well as clouds of steam from a locomotive traveling along the first railroad in the Netherlands: the line between Amsterdam and Haarlem, which opened in 1839.

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch: View of Haarlem, um 1845-1848, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, erworben von E.H. Crone mit Unterstützung der Vereniging Rembrandt

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch shows the far-reaching effects of industrialization in a cautious, almost unobtrusive way.

Some artists of the Hague School focus on images of the simple life. Jozef Israëls, a friend and role model of the German Impressionist Max Liebermann, sets his sights on the harsh existence of fishermen and farmers.

Jozef Israëls: After Dark, 1880-1896, Singer Laren, Sammlung Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed

In his dogged pursuit of real life—an approach especially valued by Liebermann—Israëls sparks a new trend: he is the first to paint the moorlands of Laren, a village easily accessible by train from Amsterdam. Soon Laren, like Oosterbeek before it, becomes an artists’ colony and attracts painters like Anton Mauve, who moves there in 1885 to depict the life of the farmers.

Meanwhile, Jacob Maris goes toe to toe with the sky: observing the heavens on an especially beautiful day, he reportedly exclaims:

Oh, what! I can do it better!

Almost all the artists of the Hague School spent a shorter or longer period of time in the forest of Oosterbeek. Around 1870, however, they turn their attention to the polder landscape in the environs of The Hague. But who are these artists?

In 1871, Jacob Maris returns to his home city of The Hague after six years in France. His brothers Willem and Matthijs also partly live and work there. Willem Mesdag and Sientje Mesdag-van Houten have already moved to The Hague in 1869, followed by Jozef Israëls and Anton Mauve in 1871.

Hendrik Willem Mesdag: Arrival of a Fishing Fleet, o.J., Dordrechts Museum, loan of the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency 2014

The white bonnets of the women of Scheveningen glow like points of light. Mesdag’s marine painting was highly sought-after, both in Holland and abroad.

Not every painter associated with the Hague School resides in The Hague. Willem Roelofs moves to Brussels in 1847, where he lives for forty years, returning to Holland in the summertime. Not until 1887, at the age of sixty-five, does he settle in The Hague.

Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël also lives in Brussels from 1860 on, only traveling to Holland to paint in the summers. Finally in 1884, he moves to Scheveningen near The Hague. How much he identifies with his paintings of the polder landscape is revealed by a description of himself noted in French in 1900: “Peintre Paysagiste des Polder Hollandais.”

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch: Polder Landscape with Windmills, 1890, Singer Laren, erworben von den Freunden des Singer Laren, 1974

The mills work to keep the polders dry.

And then there are artists like Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch—a native of The Hague, whose painting is more bright than gray—and Johan Barthold Jongkind, the great ambassador of Dutch art in Paris, who frequently travels to the coast of his homeland to paint.

The professional success of the Hague painters is strengthened by their decision to form an association, which they call “Pulchri Studio” (“For the Study of Beauty”). Although the art scene of their time and the accompanying gallery trade is only in its infancy, business rapidly expands, and soon the reputation of these new “Old Masters” of Holland extends as far as the United States.

With their echoes of tradition and of the revered seventeenth century, the works of the young Hague School are especially appealing to American industrialists, who are unable to afford great masters like Ruisdael or Rembrandt. Soon, however, even the young Hague painters command handsome prices: after the death of Anton Mauve in 1888, one of his paintings is auctioned in New York for the enormous sum of $11,000—around $400,000 in modern terms.

Hendrik Willem Mesdag: Sonnenuntergang mit Krabbenfischern, o.J., Dordrechts Museum, art exchange with the artist 1902

Not surprisingly, the artists of Holland—a great nation of seafarers and fishermen—also paint impressive beach scenes, above all in the coastal town of Scheveningen near The Hague. Here, too, the dominant elements are the sky, the peaceful atmosphere, and the color gray.

Jongkind, who mostly lives in Paris but returns to his homeland to paint on a regular basis, captures coastal scenes so perfectly that Claude Monet praises him as the “only good painter of sea pictures.” Jongkind’s loose brushwork inspires Monet, who is twenty years his junior, thus making him a precursor of Impressionism in France.

Johan Barthold Jongkind: Cityscape of Rotterdam: Canal à Rotterdam , 1873, Museum Rotterdam

The tall format of the painting—about 115 cm in height—emphasizes the sense of verticality and seems tailor-made for a dominant sky.

Jongkind’s moonlit night scene is a pre-Impressionist tour de force. Although the motif of the full moon had degenerated into a cliché since Romanticism, Jongkind’s visible, energetic brushstrokes give his glittering nocturnal views, for which he is highly esteemed, a modern look.

Perhaps too modern? The jury of the 1873 Salon in Paris rejects his painting Cityscape Rotterdam: Canal à Rotterdam. Deeply offended, Jongkind resolves to never exhibit again—and so refuses the invitation to participate in the now-famous exhibition of 1874 in Paris that marks the birth of the Impressionist movement ...

Gray, realistic, alive.

The boats in the roughened sea, a hint of danger.

Isaac Israels: Mars’s Millinery Store on the Nieuwendijk in Amsterdam, 1893, Groninger Museum on loan from the J.B. Scholtenfonds foundation

An elegant woman walks directly past the viewer; we almost feel as if we could catch a whiff of her perfume. Glimpsing her delicate, veiled face, we see the massive city blocks of Amsterdam behind her; only an angular patch of pale gray sky is visible above. George Hendrik Breitner’s The Singel Bridge at the Paleisstraat in Amsterdam shows the life of the big city at close range. The picture has such a sense of immediacy that in 1896, a perplexed critic observed: “The placement of the figure—even if divided by the frame, with only half the body visible—is certainly intentional”; yet “the execution harms the intention.”

George Hendrik Breitner: The Bridge over the Singel at the Paleisstraat, Amsterdam, 1898, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Mr and Mrs Drucker-Fraser Bequest, Montreux

Big city life at close range

Breitner originally painted a lower-class woman. But when a critic dismisses her as an “Amsterdam street girl of the usual type,” Breitner’s dealer intervenes and asks the artist to change the provocative figure. And so with the addition of a fur coat, fashionable hat, and veil, the “street girl” becomes a bourgeois lady ...

The gray light of the Hague School now yields to the artificial illumination of the big city. An 1899 description by the writer and painter Jacobus van Looy conveys an almost expressionistic mood: “He saw great red lights, balloons carried on sticks, rocking to and fro like colored moons; they resembled bloody disks of fire in the dark waters of the canals.”

Jacobus van Looy: Orange Festival, 1890-1892, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, A. van Wezel Bequest, Amsterdam

The Amsterdam Impressionists celebrate the energy of urban life in all its facets. Under their brush, the city is transformed from a backdrop into the primary motif, especially in the work of two artists who began painting in Amsterdam in 1886–87: Breitner and Isaac Israëls, the son of Jozef Israëls. They become the pioneers of urban Impressionism, the first avant-garde movement in Dutch painting.

Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, gift of the Friends of Kunstmuseum Den Haag

George Hendrik Breitner: Girl in a Red Kimono (Geesje Kwak), 1893

Breitner creates nocturnal views of Amsterdam in which reflections of light—or rather, brushstrokes—flicker across the picture like flashes of lightning. His painting of a girl in a red kimono, on the other hand, seems much quieter—yet it too has a breathless quality, dashed onto the canvas wet-in-wet, without preliminary drawing.

This improvisational quality is visible in the girl’s face: the anatomy is barely suggested, the expression seems blank. But what is it meant to convey—ennui, arrogance, diffidence?

Floris Arntzenius: The Beach of Scheveningen, 1900, Dordrechts Museum, on loan from the Collection De Rietgors, Papendrecht, 2017

Urban Impressionism focuses primarily on human beings—as do the beach paintings from the same period. The tourists who discover the coastline as a holiday retreat, however, look different from their modern-day counterparts: the men wear suits, the women are clad in frilled dresses and hats. Bare skin appears only rarely, among the working class or in groups of young people. The ladies, incidentally, often hold parasols. Here, nobody wants a tan: pale skin is considered more genteel. And just as in the city pictures, the broad sky gives way to human figures.

Ferdinand Hart Nibbrig: At the Dunes, Zandvoort, 1891-92, Singer Laren, gift of P. J. Hart Nibbrig, 1981

The painter portrays his fiancée together with her sister.

The rapidly painted, spontaneous quality of Ferdinand Hart Nibbrig’s portrait of his fiancée also characterizes the café scene At Scheveningen by Anton Mauve.

Anton Mauve: At Scheveningen, um 1876, De Mesdag Collectie, Den Haag

Two middle-class women in the center of the picture gaze out toward the sea. The waiter, holding a tray with a white cloth over his arm, looks the other direction, toward his guests: a social reality, spontaneously sketched in oil. We can see the artist’s reworkings and the unfinished, sketch-like character of the image.

Isaac Isreals: Donkey Riding on the Beach, 1890-1901, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Mr and Mrs Drucker-Fraser Bequest, Montreux

Isaac Israëls’s Donkey Rides on the Beach also has a snapshot-like quality, the result of his rapid method of painting:

Above all, don’t work too much, no more than two hours on a piece, don’t think about it too much, then you’re no longer fresh.

Anton Mauve: In the Vegetable Garden, 1887, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Nachlass J.P. van der Schilden 1925

The poorer classes wear dark clothing and labor in the garden. The more well-heeled personages, generally dressed in light colors, immerse themselves in the sophisticated aesthetic of the brilliantly colored flowers—just like the painter.

Jacobus van Looy: July ("Summer Luxuriance"), 1900, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, gift of friends of the artist, on long-term loan to Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Lupine splendor in front, sweating farmers on hay wagons in the back

Jan Toorop: Trio fleuri, 1885, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague

Beauty in white dresses, with echoes of French Impressionism

Although Impressionism varies widely in different countries, paintings of flowers and women in white dresses often look quite similar, regardless of the painter’s nationality. Everywhere in Europe, the next aesthetic phase is beginning to emerge ... Why should artists keep painting flower gardens when they can dissolve the entire world into a bouquet of Pointillist colors?

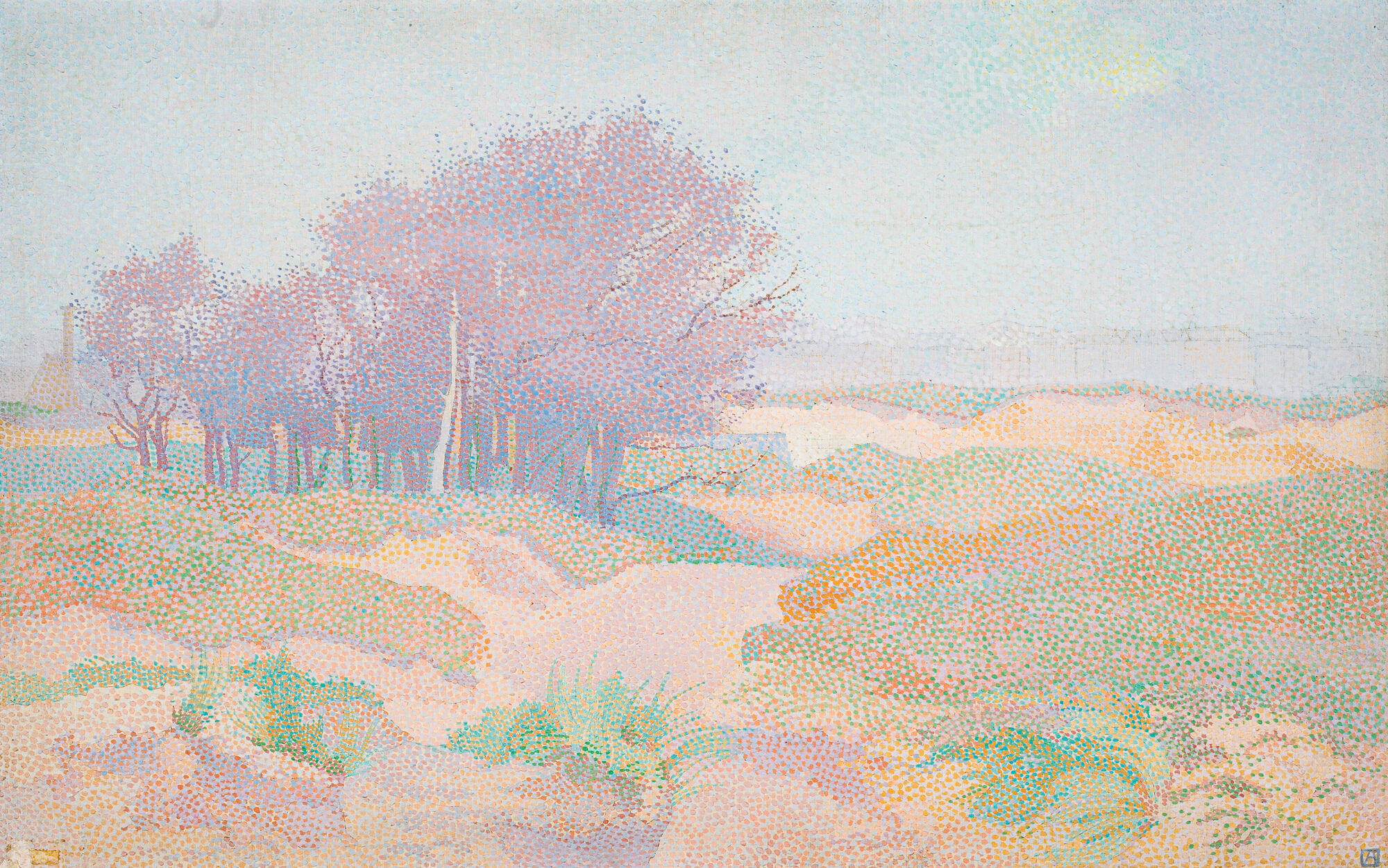

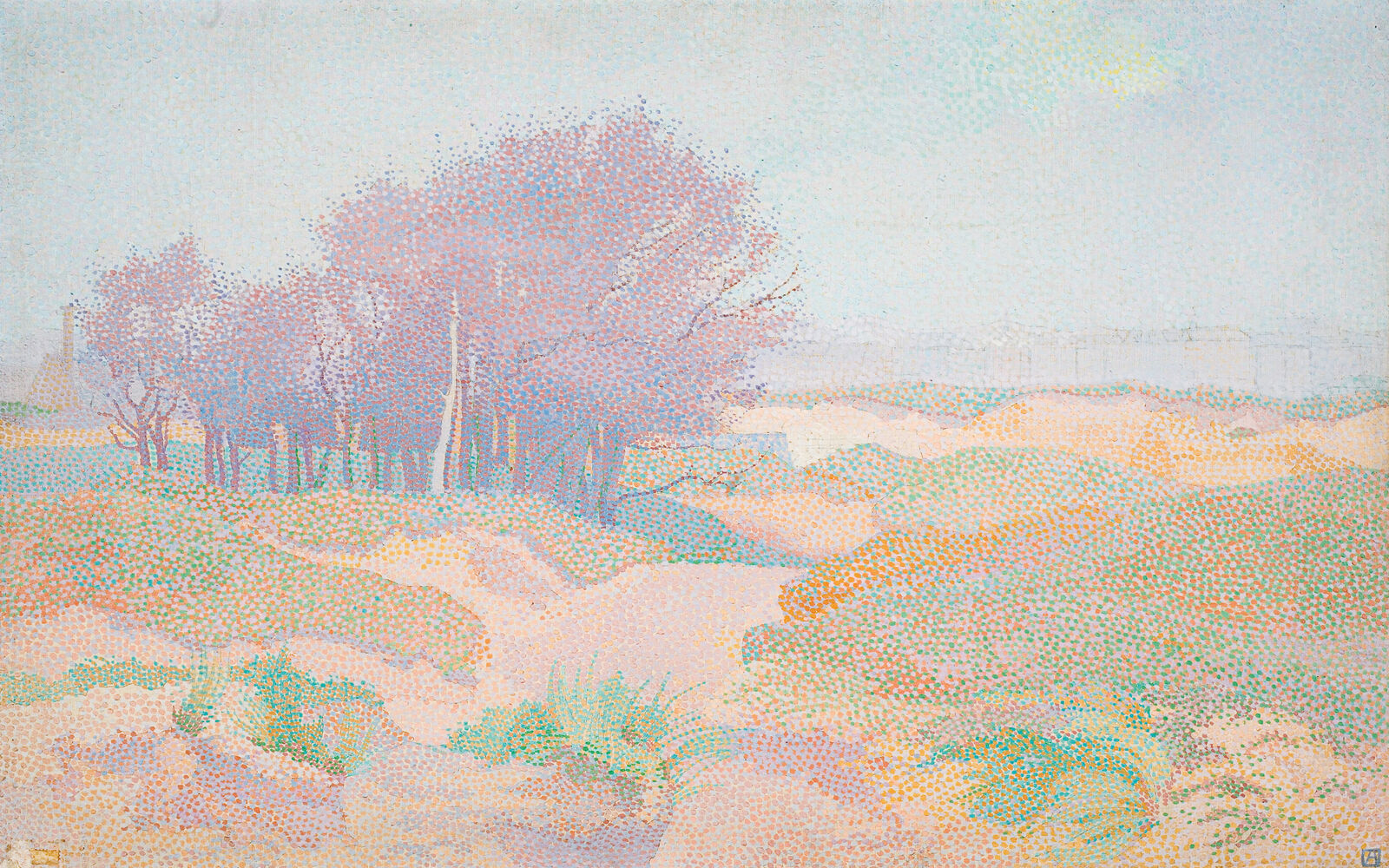

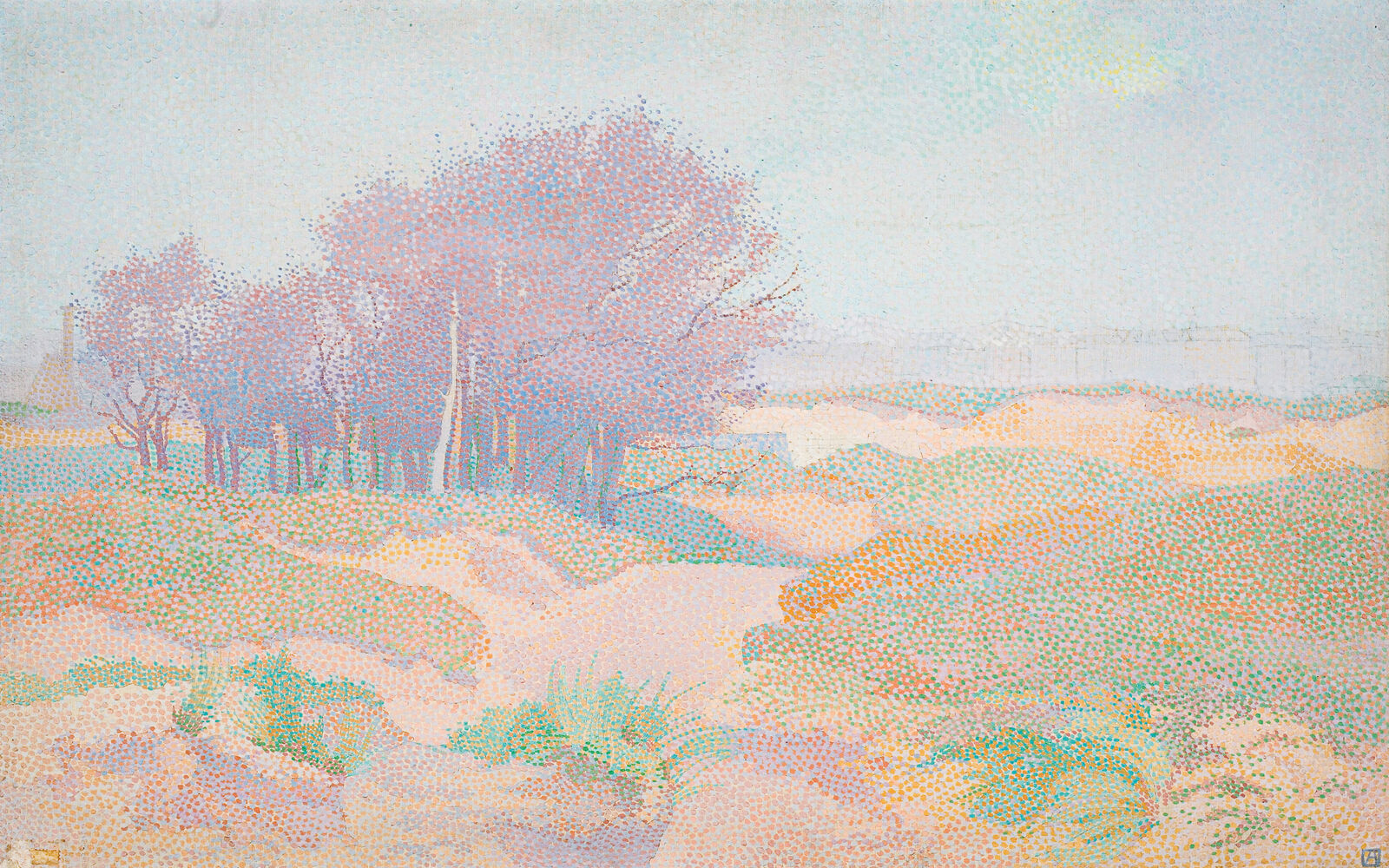

Johan Joseph Aarts: Landscape with Dunes, 1895, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo / Photo: Rik Klein Gotink

Pointillism is based on a (not entirely accurate) theory of optics. Between 1884 and 1886, the French artist Georges Seurat develops a painting technique in which he juxtaposes individual dots of differing colors. According to theories of the time, the mixed colors separated in this way combine again in the eye of the beholder. This approach also becomes widespread in the Netherlands, especially through the influence of Jan Toorop.

By 1892, Toorop has already moved on from this way of seeing and painting—but the artists he inspired, like Hendricus Petrus Bremmer, are just getting started.

Hendricus Petrus Bremmer: Trees Along the River Ijssel, 1901, John & Marine Fentener van Vlissingen Art Foundation, © Aleida Mosselman-Takens

If you squint your eyes, the dots blend together ...

Bremmer’s Pointillist work from the 1890s on accomplishes a decisive step toward modernism by introducing autonomous color. Increasingly, painters are turning their backs on realistic representation in favor of color and emotion.

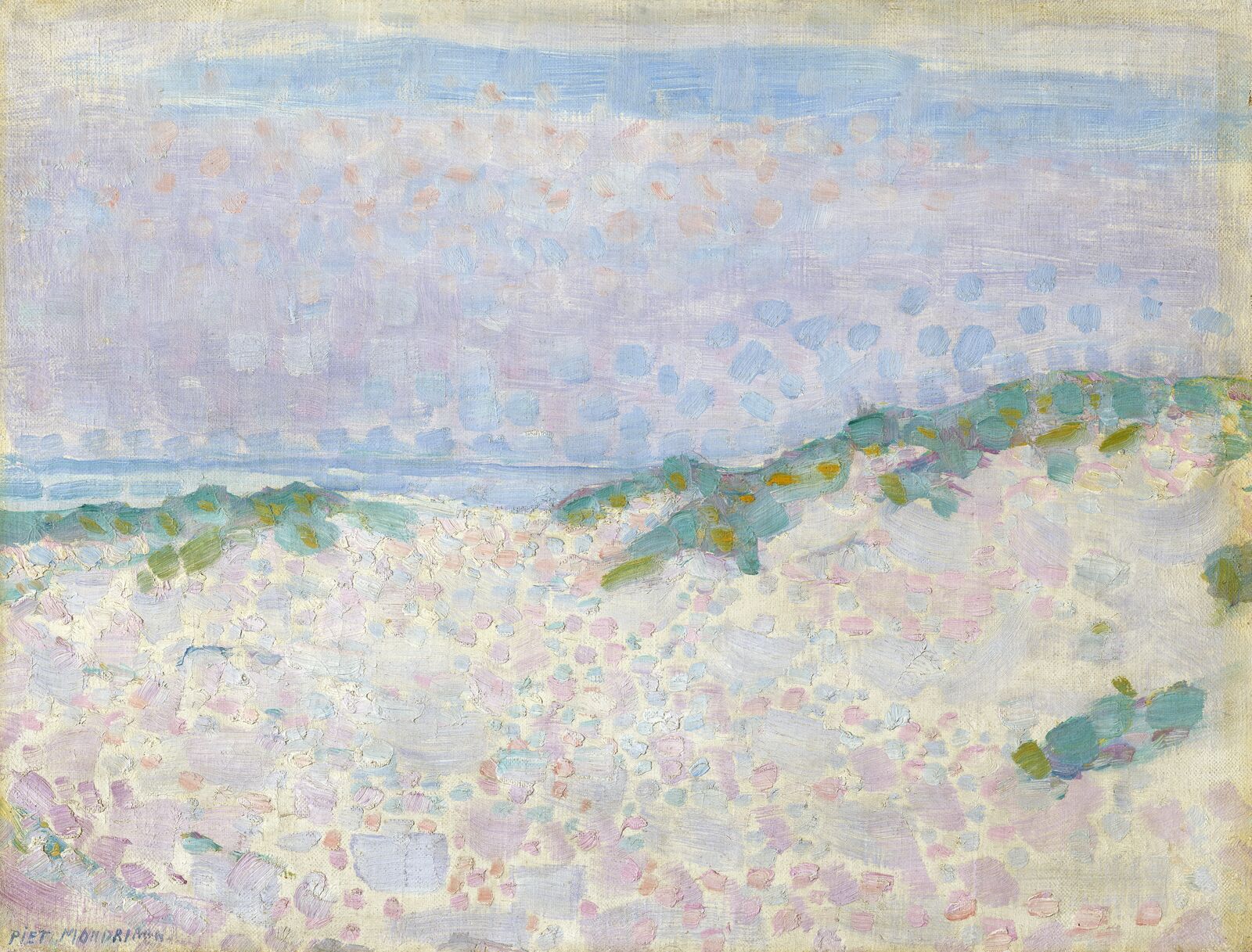

Piet Mondrian: Pointilistic Study with Dunes and Sea, 1909, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, long-term loan private collection

The “blue hour”: a painterly stroke of genius

Mondrian’s Pointillist study is a stroke of genius. He captures the mood of the so-called “blue hour” more profoundly and beautifully than almost anyone else: in this atmospheric moment, the world and the soul truly become one in the colors of the dusk.

Feel with me this flood, this brilliant glow ...

Piet Mondrian: Mill at Domburg, 1908, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague

Night takes on a life of its own and descends upon the earth—as color!

The emancipation of color reaches a high point in Mondrian’s Mill at Domburg, where he transports the quintessential Dutch windmill into the twentieth century in abstracted form. Paintings like this one cause a stir: critics are not prepared for such an excess of visual freedom. Another mill picture by Mondrian prompts the accusation that his outlandish colors are due to mental illness—a charge that is rejected as complete nonsense by the Israël Querido, who comes to Mondrian’s defense.

For Querido, the reign of the Hague School’s realism has lasted long enough:

Leave behind the sweet-summery, sleepy-sunny, beautifully painted day by Willem Maris with its white cows and bright milking scenes; leave behind the green-capricious duckweed ditches where delicate cygnets and ducklings swim; . . . Away with this art and with its cloying, yearning recollection ...

Jan Sluijters: Dumping Carts, 1907 Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam / Photo: Studio Tromp

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

Yellow and blue, red and green: brilliant contrasts of color

Jacoba van Heemskerck: Two Trees, 1910, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague

When I wanted ... to paint the sun on the landscape, I would first turn my back to this landscape and then, when I sensed the feeling in me caused by the glowing of the sun on the landscape, I would compose in yellow and blue and green.

Important players in the emancipation of color in Dutch painting are the stylistically versatile Toorop and, of course, Van Gogh. A woman collector gushes: “Vincent lives in color, he drinks color and exhausts all the possibilities of his ideal to its utmost consequences.” Toorop sets the process in motion, but from 1906 on is Jan Sluijters who advances the unleashing of color in the Netherlands. Between 1904 and 1906, Sluijters spends time in Paris, where he absorbs new artistic currents.

For the Parisian avant-garde, color is no longer a means of depicting light, but an autonomous element. In the painting of the Dutch Impressionists, the traditional principle of chiaroscuro now yields to contrasts of color. Mondrian’s poplars, for example, were originally composed in green and brown tones in the spirit of the Hague School. After an encounter with Toorop, however, Mondrian overpaints the image with energetic, vibrantly colored brushstrokes.

Piet Mondrian: Row of Eleven Poplars in Red, Yellow, Blue and Green, 1908, Museum de Fundatie, Zwolle und Heino/Wijhe

The flaming orange-red poplars in the center stand out against the clear blue sky, conveying the feeling of a radiant Dutch sunset.

This Dutch version of Pointillism, known as Luminism, is characterized above all by the spontaneous, intuitive application of color. The focus is not on the visible world, but on the emotions of the artist.

And so begins the explosion of twentieth-century styles. Now, only a few decades or even just a few years after the forest painters of Oosterbeek, the Hague School, and the Amsterdam Impressionists, everything they had achieved seems almost sentimental. Maris’s dictum “I’m not painting cows, but the effects of light”—unprecedented in the mid-nineteenth century—has now run its course; instead, avant-garde art throughout all of Europe seems to follow the pronouncement of the great Russian modernist Kasimir Malevich:

Color is also light, light is also color—depending on the circumstances.

Jan Sluijters: Moon Night II, Laren, 1911, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

Cubism creates multiple views of the object by dissecting it into geometric perspectives. Expressionism intensifies the world into all-embracing assertions of feeling. Abstraction reduces everything to nonrepresentational colors, forms, and elements of meaning. And all at the same time! Like a flood, the styles alternate, intersect, and influence one another.

Women artists also play an increasingly prominent role, with figures such as Hilma af Klint, Sonja Delaunay, or the Dutch painter Jacoba van Heemskerck, a student of Piet Mondrian.

Jacoba van Heemskerck: Bild Nr. 107, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague

Kandinsky’s compositional principles and expressionistic colorism are apparent here

By 1914, Mondrian is no longer satisfied with Expressionism. He goes in search of new solutions—and finds them. On the eve of World War I, he writes in a letter:

Nature (or the visible) inspires me, arousing in me the emotion that stimulates creation, no less than with any other painter, but I want to approach truth as closely as possible; I therefore abstract everything until I attain the essential of things.

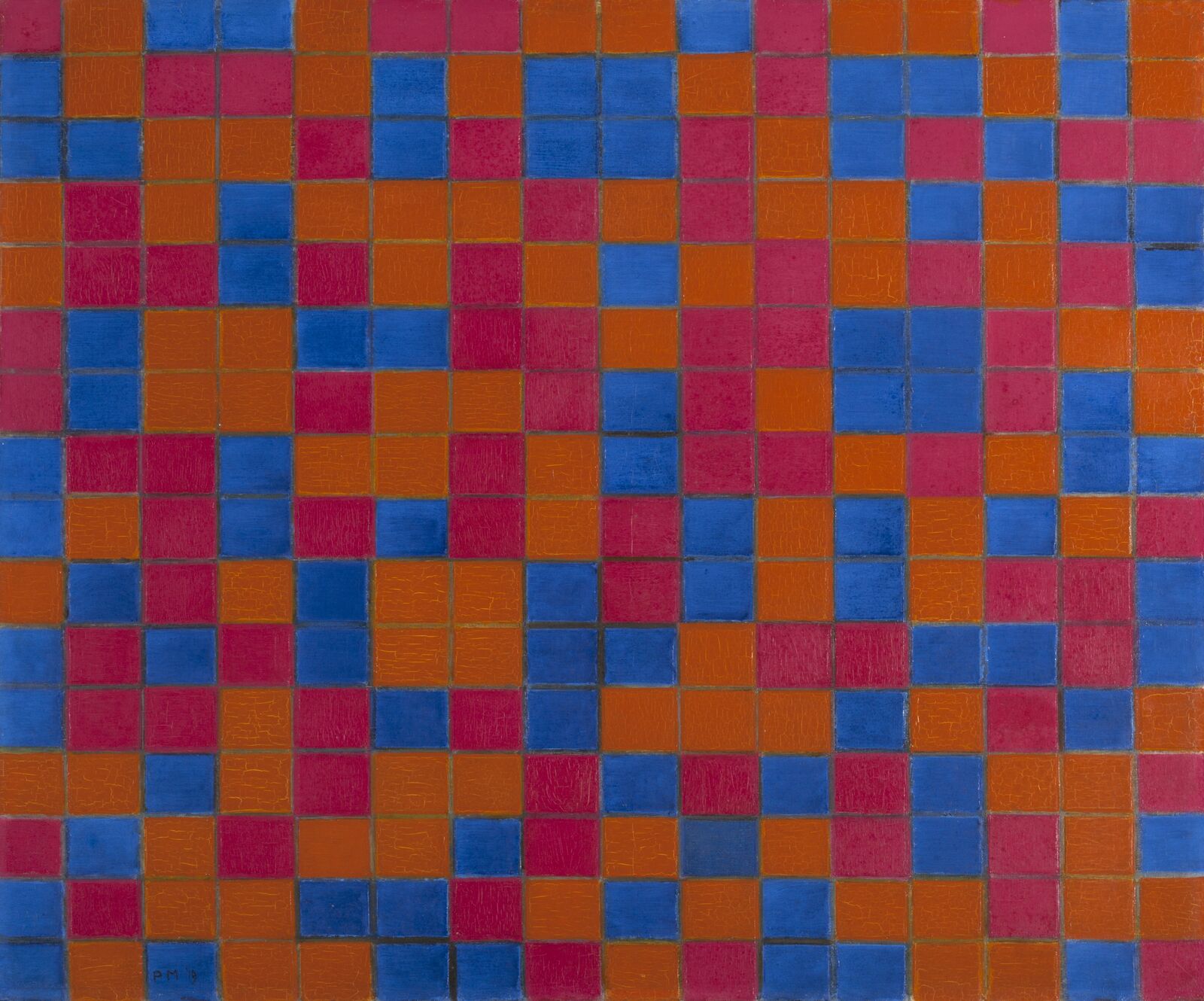

Piet Mondrian: Composition with Grid 8: Checkerboard Composition with Dark Colors, 1919, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, Nachlass Salomon B. Slijper

Abstraction and Modernity.

Mondrian’s grid paintings, reduced to the essentials of form and color, are an unprecedented aesthetic innovation and become icons of modernism.

But they did not come out of nowhere: within them are distant echoes of the gray brushstrokes of the Hague School, the brilliant, experimental color of urban Impressionism, and the bold, revolutionary spirit of Pointillism and Luminism.