Edvard Munch:

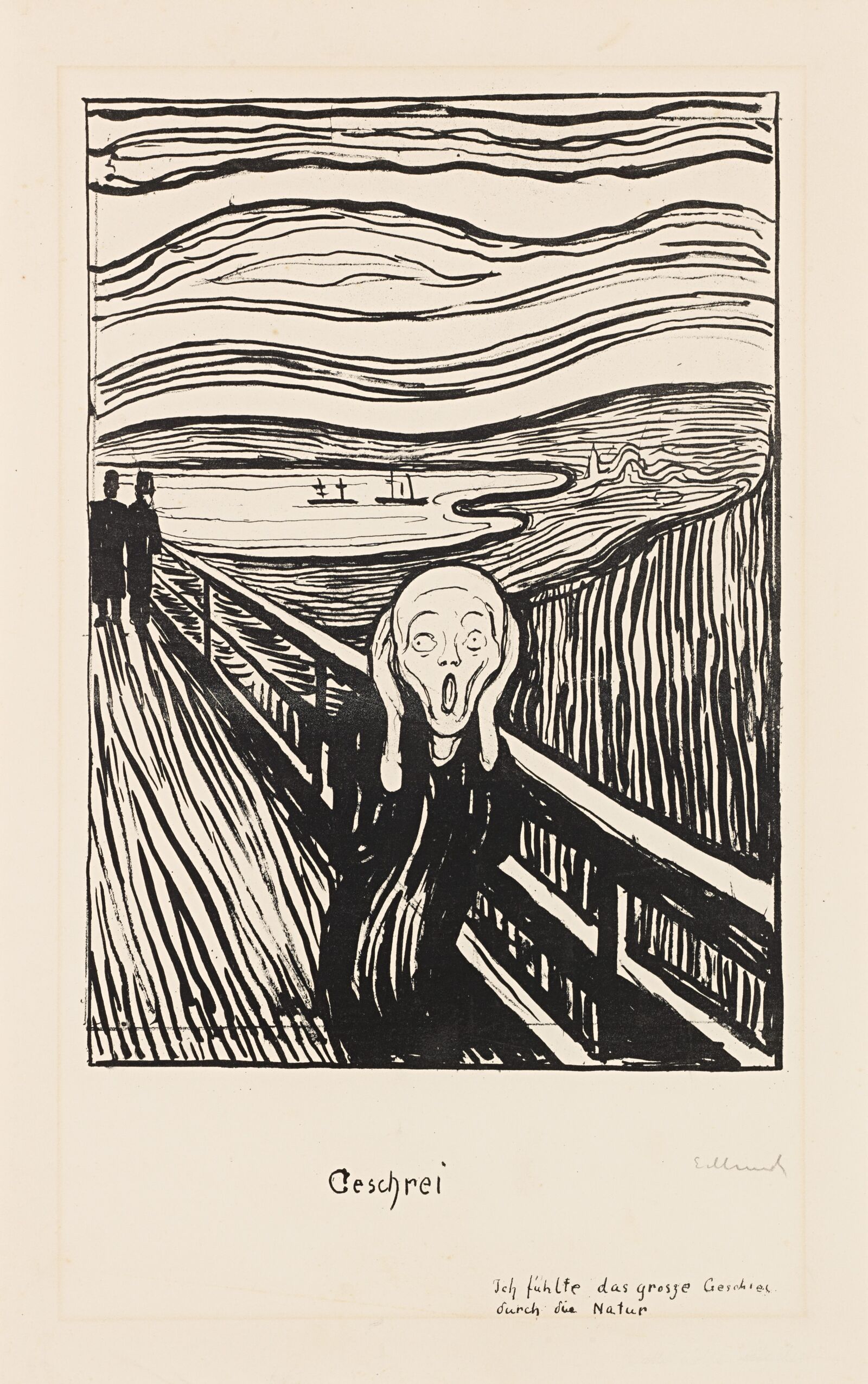

The Norwegian artist Edvard Munch is best known for his images of modern alienation and loneliness. Works like his famous painting The Scream not only monumentalize fear, but have also become a familiar part of modern pop culture. But as the exhibition Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth at the Museum Barberini shows, this perspective by no means does full justice to the work of Edvard Munch. This wide-ranging exhibition is the first to explore the Norwegian artist’s fascination with nature. As a multimedia website, the Barberini Prolog offers an overview of this new look at Munch, the works of art that will be on view in Potsdam until April 2024, and the themes addressed in the show.

Edvard Munch: Dark Spruce Forest, 1899, Munchmuseet, Oslo

In Munch’s painting Dark Spruce Forest, the green fir trees emanate a sense of calm.

They went into an opening in the forest [...] they walked up and down silently, heads bowed — they were enveloped in an atmosphere of solemnity, as though in a church.

The perception of Munch as a fin de siècle artist drinking his nights away in Berlin is only part of the story. For most of his life he was a landscape painter, a student of nature, a pantheistic natural philosopher with a brush. It is no coincidence that over half of his pictures are landscapes: his expressive painterly approach, which supersedes Impressionism and anticipates Expressionism, seeks a path out of modernism and into the realm of the organic, cosmic, and spiritual.

In 1908, a nervous breakdown prompted Munch to leave Berlin and check into a clinic near Copenhagen. There he finally came to terms with his alcoholism, and shortly thereafter returned to his home in Norway.

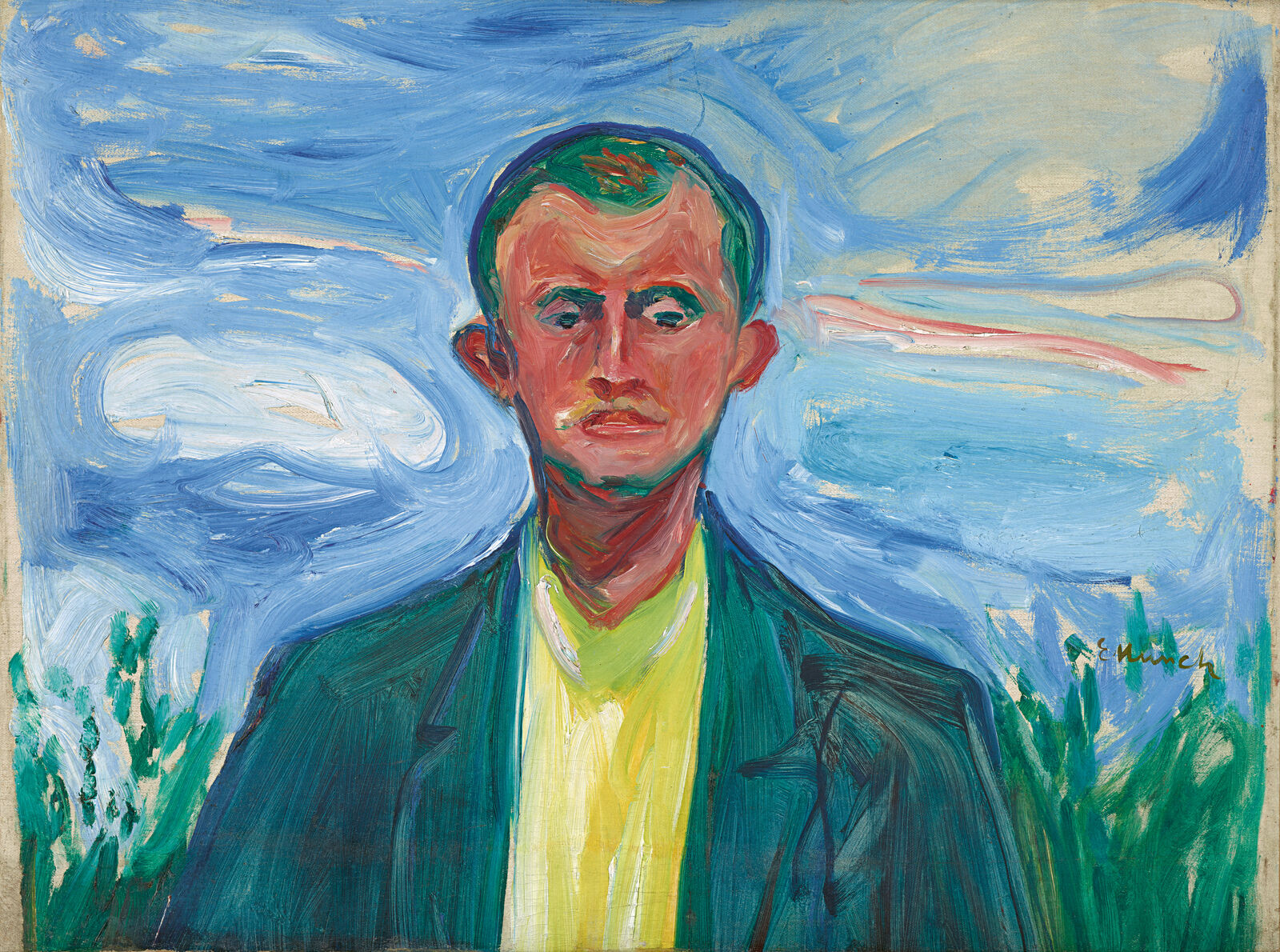

Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait against a Blue Sky, 1895, Munchmuseet, Oslo

In Self-Portrait Against a Blue Sky, Munch shows himself as part of nature, with an expressive sky that seems to embody his inner life.

As the first exhibition of its kind, Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth, a cooperation of the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, the Museum Barberini, and the MUNCH in Oslo, focuses on this imaginative, almost tender side of the artist, exploring the expansive imagination and keen perception that enabled Munch to find the human within the landscape and the cosmic within the human.

Painterly, atmospheric works like House in the Summer Night from 1902 evoke what might be called the poetry of existence. Here there is no civilizational anxiety; it is not the world that is ending, but only a day.

Edvard Munch: House in the Summer Night, 1902, Private collection

A clear, starry night, a silent house, a mysterious glow...

Munch’s conception of nature is pantheistic. He sees the universe in the world, the cosmos in human beings, and each human being as a cosmos:

A drop of blood is an entire world within its own sun and planets. The sea is but a drop of water from a tiny part of the body.

The art of Edvard Munch establishes a powerful connection between the human figures and the surrounding landscape. He paints anthropomorphic forms into trees, stones, sky, and water — as in View from Nordstrand, where the island in the vivid blue water resembles a mouth.

Edvard Munch: View from Nordstrand, 1900/01, Kunsthalle Mannheim

Photo: Margita Wickenhaus

Is it an island, or a giant mouth? Are those trees on the shore, or dark spirits? Only one thing is certain: the human figure is alone.

In the pale nights, the forms of nature have fantastical shapes. Stones lie like trolls down by the beach. They move.

With no protective greenery, the reddish ground of the forest seems almost organic, like a wound.

Edvard Munch: From Thüringerwald, 1904, Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., bequest of Mrs. Eugene McDermott

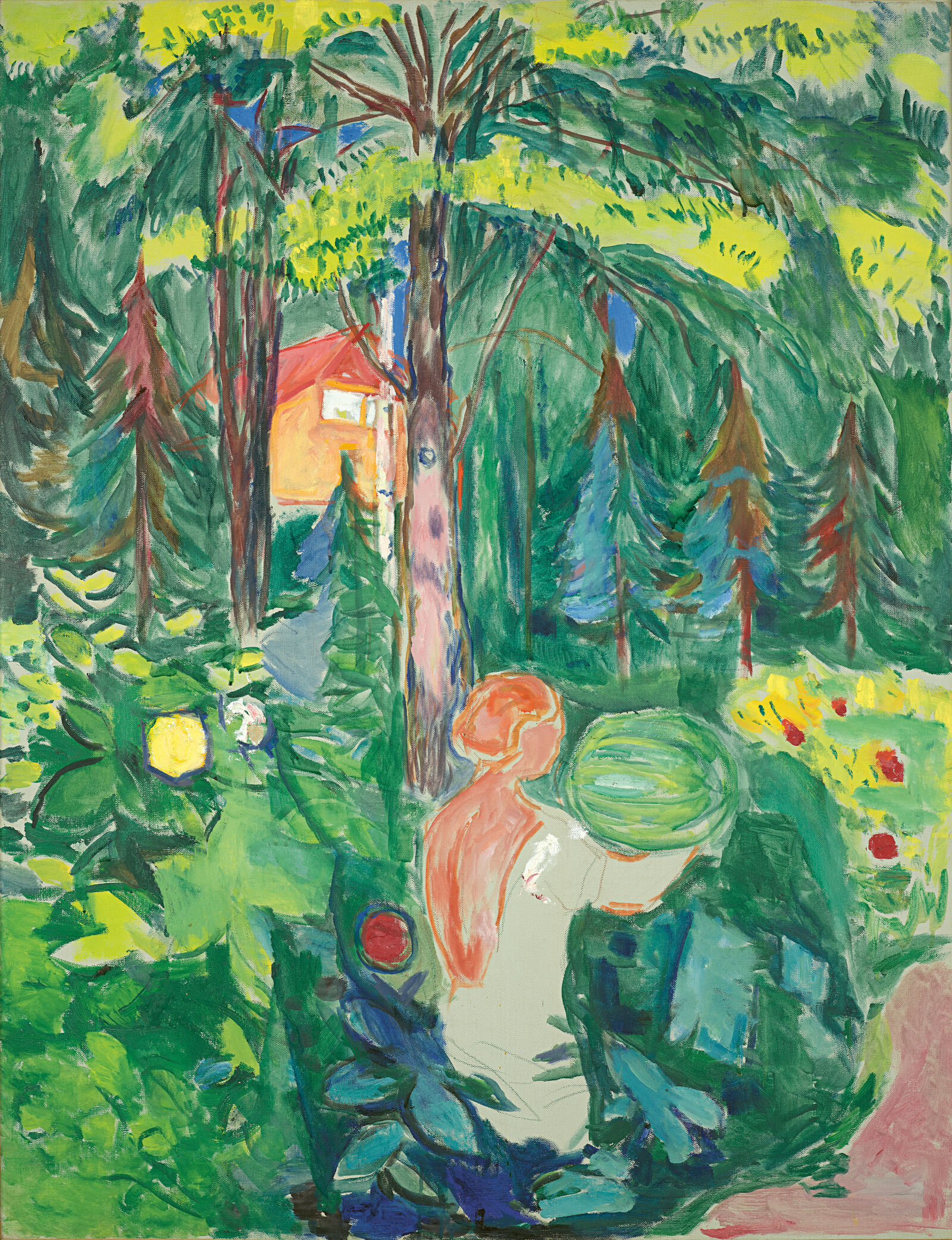

Edvard Munch’s life was marked by periods of psychological instability. Following a nervous breakdown in 1908 and repeated courses of treatment, he was finally able to overcome his depression and alcoholism. After years of turmoil, he moved to the Norwegian coastal town of Kragerø, where he lived from 1909 to 1915. At Skrubben, his house there, he worked in an open-air studio. Abandoning himself to nature, he gave up the city almost entirely as a motif.

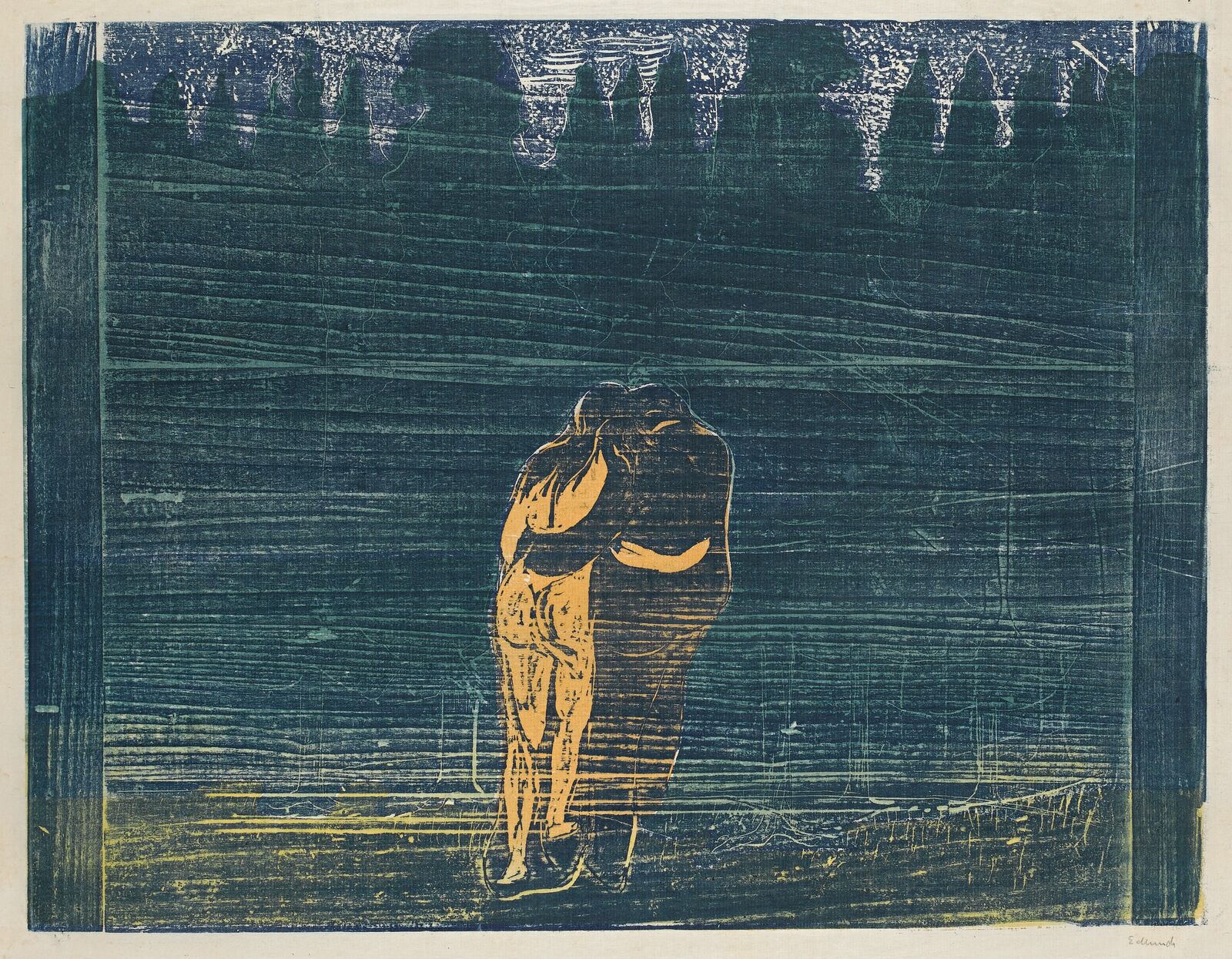

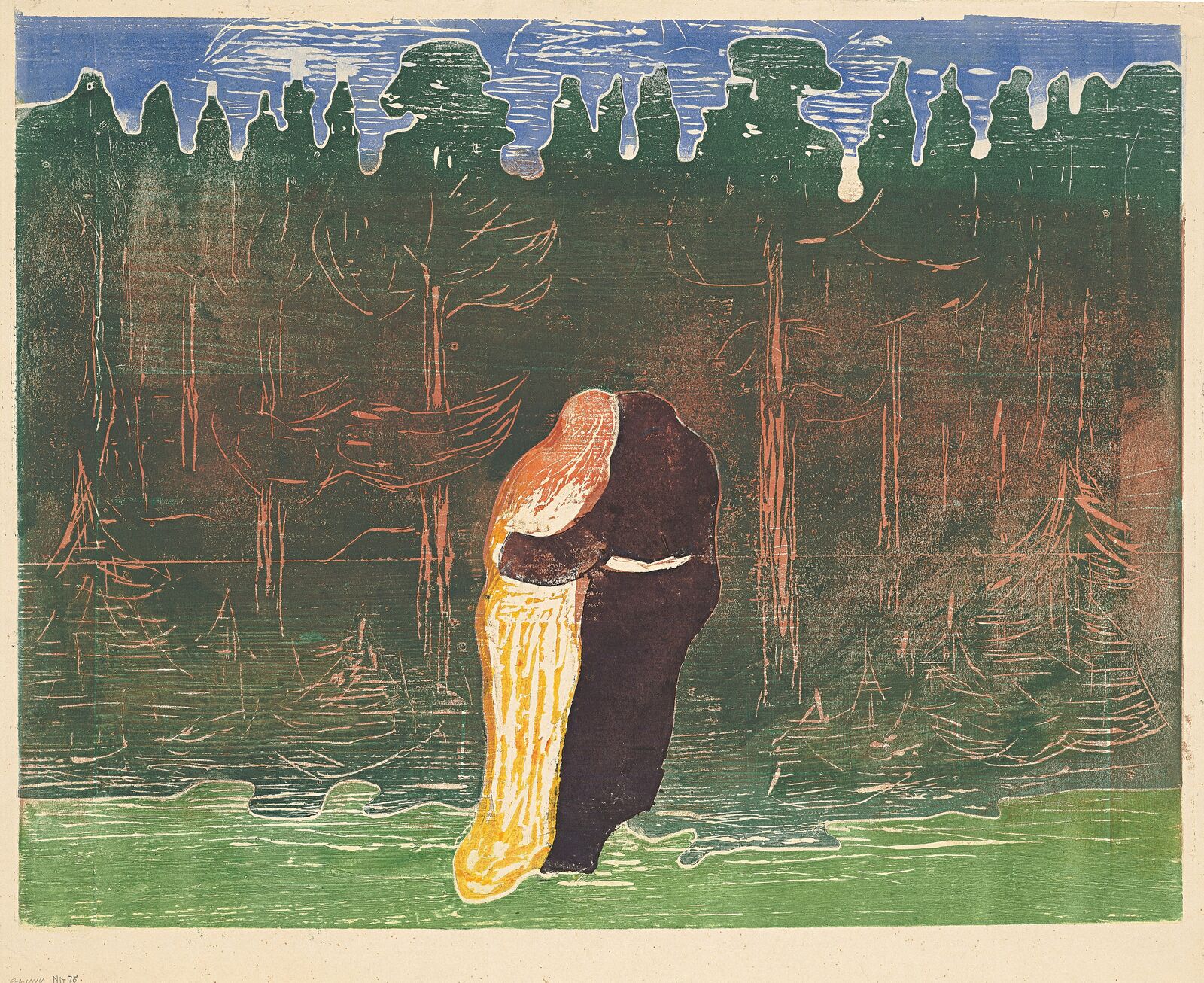

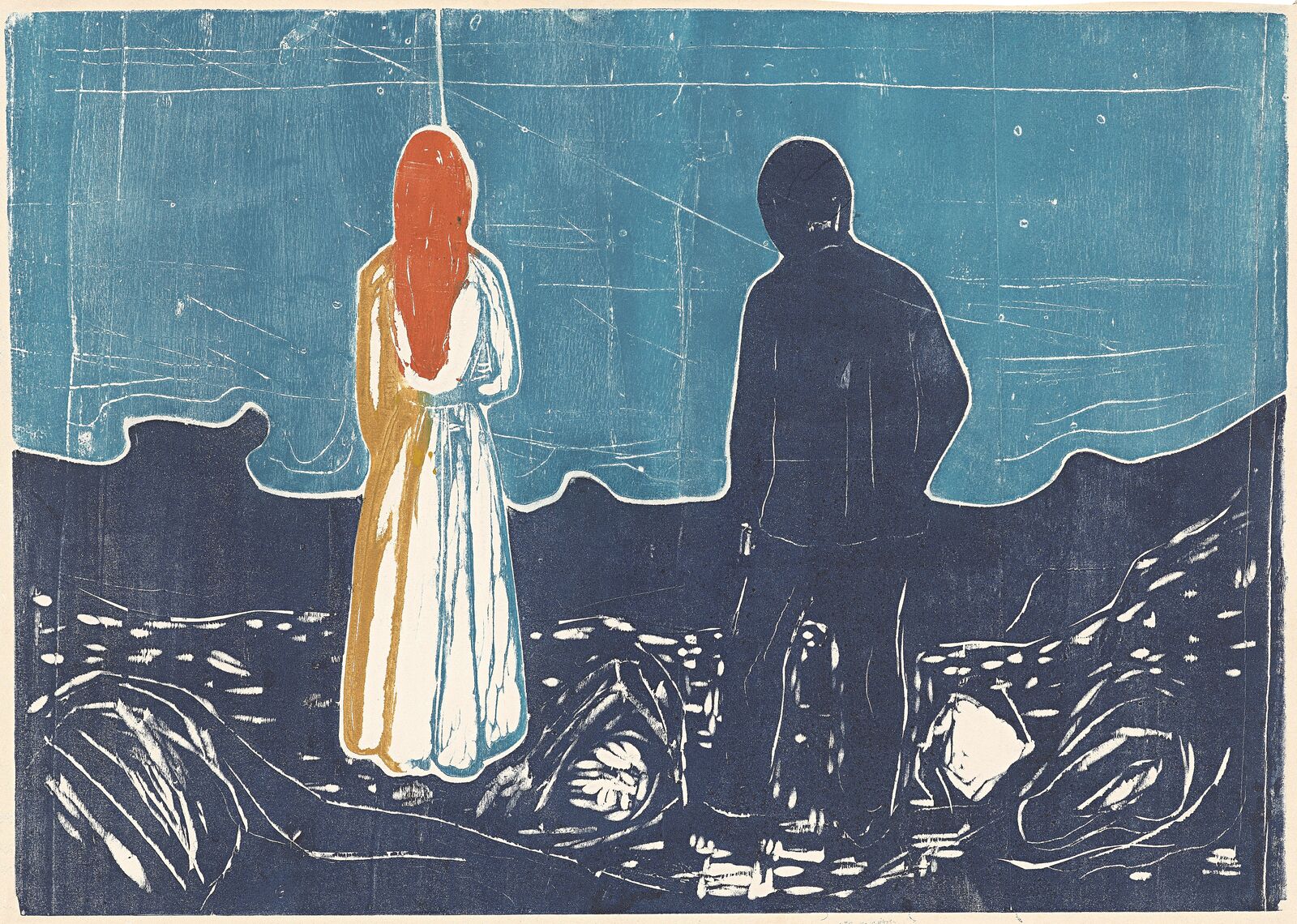

His images of trees and forests often show love stories — as in Towards the Forest, a series of woodcuts that he varied over the course of decades. For Munch, wood was a living material, and his woodcuts integrate the material of the block, the wood grain, into the picture: a true interpenetration of art and nature.

Edvard Munch: Towards the Forest I, 1897, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Graphische Sammlung, loan 2008

Six variations of a scene: the man and woman are so close they almost become one.

Edvard Munch: Towards the Forest II, 1915, Munchmuseet, Oslo

The character of the woman changes with the color, but the dark figure of the man remains the same.

In Munch’s art, couples are often “alone together,” shown in tremendous isolation. Here, however, the man and the woman nestle close to one another. Around 1890, the artist noted:

They went into an opening in the forest — on both sides stood tall conifers and birches — lush and dark against the twilight evening air.

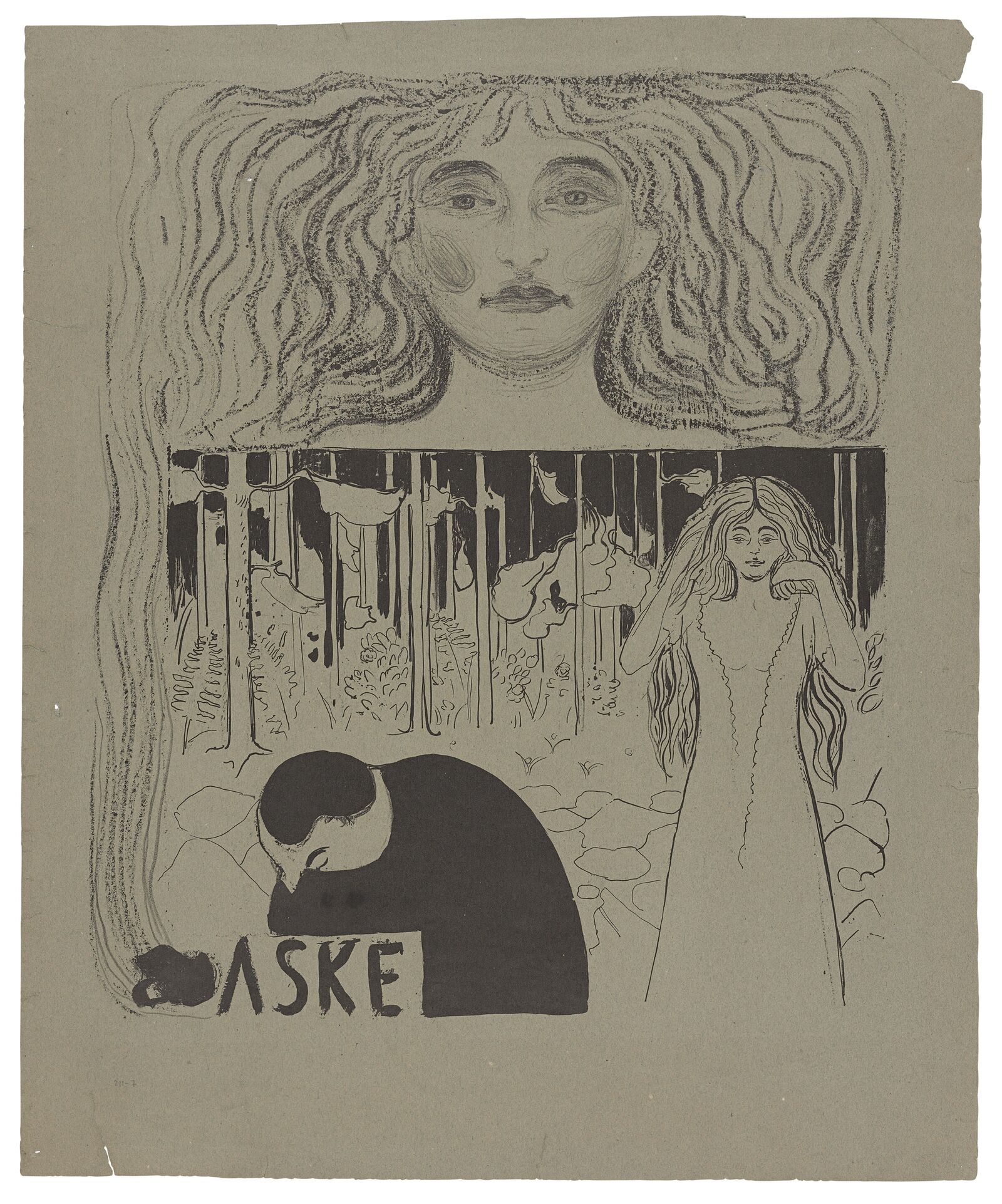

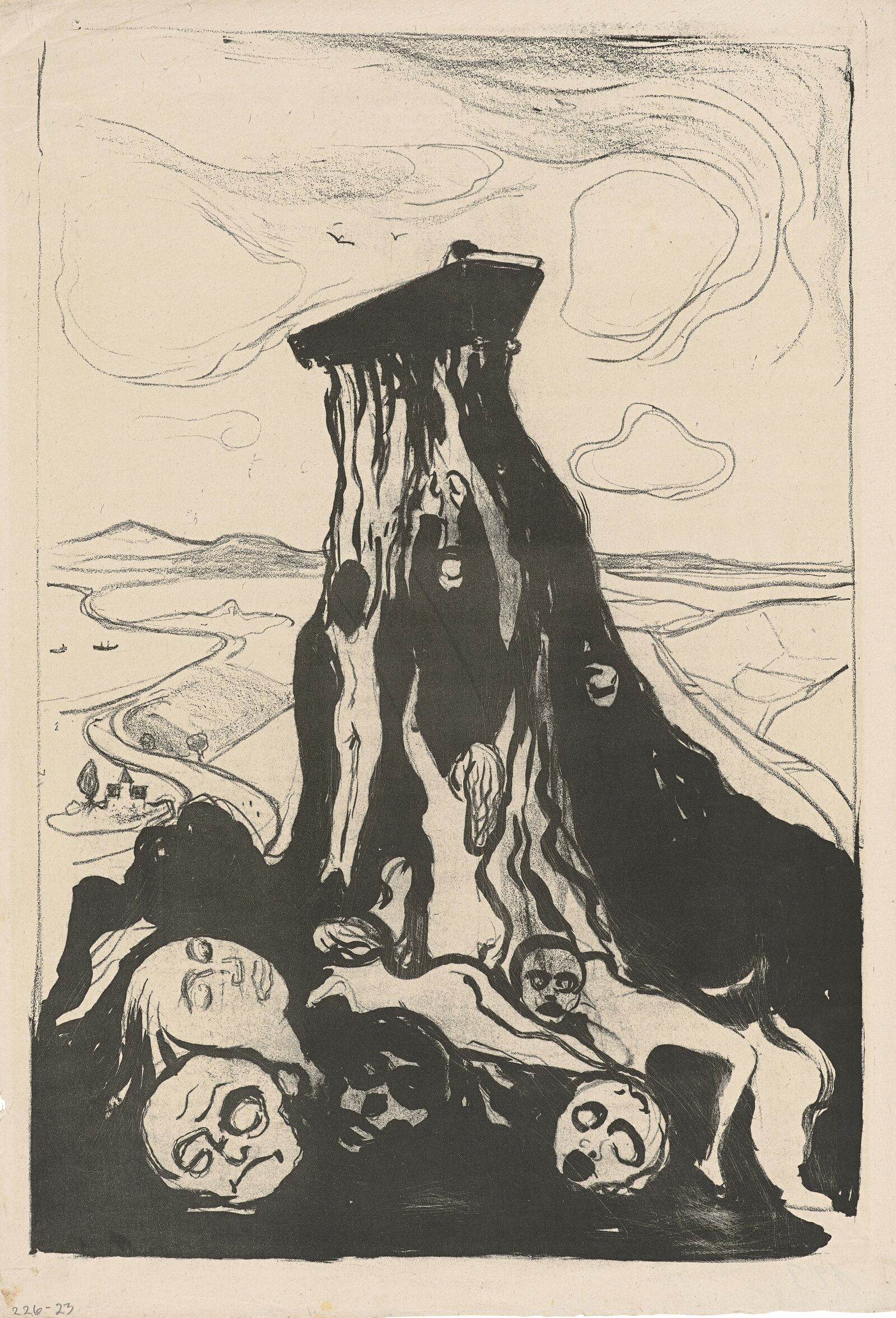

A moment of unity. But the scream of nature, the biblical curse, the Darwinian struggle for existence can always rear its head — as in Ashes, a series of prints that alludes to the Old Testament. Here Adam and Eve, banished from Paradise, have to survive by the sweat of their brow.

Edvard Munch: Ashes I, 1896, Munchmuseet, Oslo

In Ashes I, the woman’s hair cascades downward on the left, leading to the stooped figure of the man and the title inscribed below.

Edvard Munch: Ashes II, 1899, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett

Photo: bpk / Kupferstichkabinett, SMB / Dietmar Katz

Ashes II shows a variation of this unholy twosome.

Munch lost his mother at the age of five and his sister when he was fourteen. The loss and grief that defined his childhood recurs in his art, even in works created decades later. The Magic Forest, painted from 1919 to 1925, is marked by a sense of tremendous forlornness. In other paintings such as Children in the Forest, this drastic quality is less pronounced: while the charming, colorful group of children confronts a vast, dark sea of green trees beneath a turbulent evening sky, the mood of the image is not one of terror, but of adventure.

Edvard Munch: The Magic Forest, 1919-1925, Munchmuseet, Oslo

Holding hands, a mother and her child venture down a path between tangled trees that rise up from the vividly painted ground.

Edvard Munch: Children in the Forest, 1901-02, Munchmuseet, Oslo

Children in the Forest: a masterpiece with fairy-tale atmosphere.

Created almost two decades apart, these paintings show that the divide between the more tormented and happier phases of Munch’s life is far from clear in his work. Children in the Forest was painted much earlier than The Magic Forest, during the artist’s time in Berlin, a generally darker period than the years after his return to Norway.

This continuity of feeling is also evident when we compare Dark Spruce Forest of 1899 with From Thüringerwald, created six years later. The spruce forest recalls the fairy tales of Norwegian author Theodor Kittelsen; From Thüringerwald, on the other hand, seems like a projection of Munch’s own existential despair onto the landscape.

Edvard Munch: Dark Spruce Forest, 1899, Munchmuseet, Oslo

In Munch’s painting Dark Spruce Forest, the green fir trees emanate a sense of calm.

Edvard Munch: From Thüringerwald, 1904, Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., bequest of Mrs. Eugene McDermott

With no protective greenery, the reddish ground of the forest seems almost organic, like a wound.

Nothing passes away — there are no examples of this in nature — the body that dies — does not disappear — the matter dissolves — is transformed.

Around 1900, a new environmental consciousness began to emerge. For Munch, always searching for meaning, these ideas fell on fertile ground. He often spent time with the economist and writer Christian Gierløff, whose family had made their fortune in the timber trade. In The Yellow Log, the glowing vitality of the tree trunk symbolizes the growth and disappearance of the Norwegian forests as well as death and transformation. Even today, the painting seems so fresh and unusual that the New York Times immediately observed that this is not “Munch-as-usual”!

Edvard Munch: The Yellow Log, 1912, Munchmuseet, Oslo

The tree, stripped of its bark, glows in the pine forest like a symbol of beginning and end.

Edvard Munch: Fertility, 1899/1900, Canica Art Collection, Oslo

As the metropolises swelled, the railroads conquered Europe, and industry swallowed up entire swaths of land, a countermovement to this technologized alienation began to arise: a call back to the land, back to cultivated nature. From 1909 on, Munch became a passionate proponent of rural life, although his earlier painting Fertility had also expressed this attitude in its depiction of a couple harmoniously engaged in agricultural activity. Even there, however, there are moments of disturbance: the light-colored wood of a sawn-off branch stands out like a wound, and it almost seems as though the couple were bending toward the tree to care for it. Here, nature does not separate, but unites.

Edvard Munch: Cabbage Field, 1915, Munchmuseet, Oslo

In works like Cabbage Field, Munch shows the visible signs of human activity in the landscape.

Like a dance around an invisible harvest, the girls stretch out their arms toward the trees.

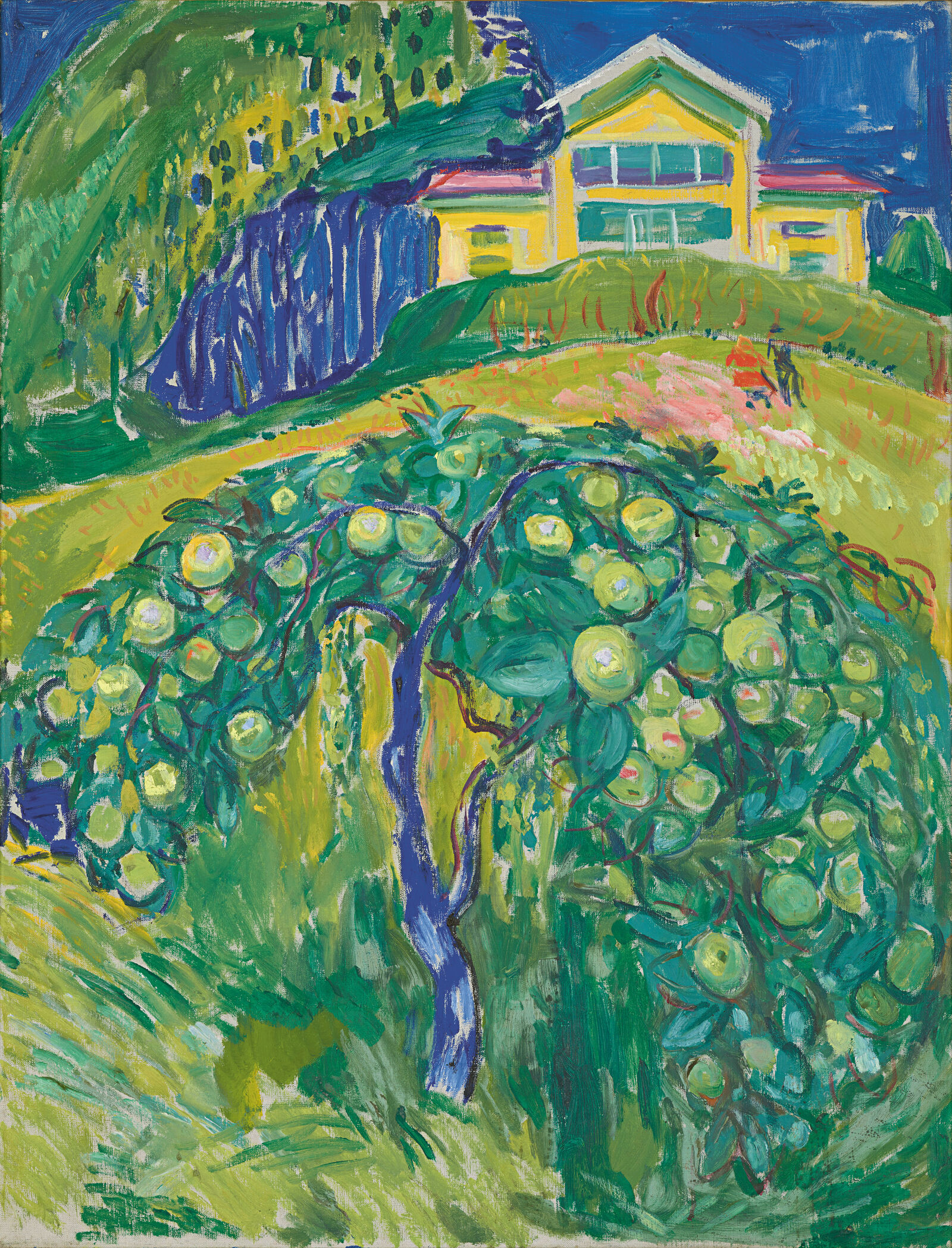

In the coastal region near the fjord of Oslo, Munch bought and rented various houses in Åsgårdstrand, Kragerø, Hvitsten, and on the island of Jeløya. There he planted gardens: at his house in Åsgårdstrand, he tended berry bushes and apple trees, while in Hvitsten he cultivated an extensive orchard and kept hens, doves, ducks, a dog, and a horse.

Munch’s last home at Ekely on the outskirts of Oslo was originally a plant nursery. It was still so fertile during his lifetime that he was able to supply his family with fresh produce during World War I — as evidenced by the abundant harvest in Apple Tree in the Garden.

Edvard Munch: Digging Men with Horse and Cart, 1920, Munchmuseet, Oslo

Despite the men’s hard labor, the scene has a harmonious effect.

Edvard Munch: Apple Tree in the Garden, 1932-42, Munchmuseet, Oslo

Munch often portrayed his garden as a green, overgrown jungle.

The soil of the earth longed for the air.

In the late masterpiece Woman with Pumpkin, the female figure in the foreground holds the giant vegetable. The house in the distance, almost completely overgrown, glows in delicate tones of reddish-orange that are also echoed in the woman’s hair. In this work, painted two years before his death, Munch once again united the forms of plants, architecture, and the human figure as if to embody the balance between civilization and nature in the garden.

Edvard Munch: Woman with Pumpkin, 1942, Munchmuseet, Oslo

A late masterpiece by Edvard Munch: the total harmony of humanity, culture, and nature.

Edvard Munch: Summer Night by the Beach, 1902/03, Private collection,

He sees in wave lines, he sees the shoreline weave next to the ocean [...] he sees women’s hair and women’s bodies in waves.

Munch spent most of his life near the fjords around Oslo, but also paid frequent visits to Warnemünde on the Baltic Sea. The seashore was and remained one of his primary motifs. For Munch himself, the coastline evoked the “perpetually shifting lines of life.” Moonlight and summer nights play an especially prominent role in his images of the coast; not only does he imbue his coastlines with profound feeling, he also captures the mood of the midsummer light so typical of Scandinavia, where even the darkness seems to glow.

Edvard Munch: Moonlight, 1895, The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

Photo: Børre Høstland

A summer night, a deserted coastline — or does a human figure emerge from the juxtaposition of shore, moon, and reflection?

Some of the coastal images tell stories of couples parting, like the lithograph Separation II. The figures always react to each other and to the landscape; they are clearly connected to or isolated from one another. Here, the woman’s hair repeats the form of the coastline and waves; it moves toward the man and falls across his heart. From the left edge of the picture, branches extend over the man’s head toward the woman, their leaves like an echo of her flowered dress. Who is leaving whom?

The color woodcut Melancholy II shows the solitary figure of a woman — an unusual motif for Munch, since for him it is usually the men who are alone. The few impressions of this print were made by the artist’s own hand; for woodcuts like Evening. Melancholy I and Melancholy III, however, he had the images professionally printed in larger editions.

Munch’s typical loneliness in a woodcut...

For Munch, everything that arises in and from nature has a soul [...]. The earth, nature has the gender of a woman, it is fertile, stirring, and enticing.

All the printmaking techniques — not just woodcut — find unprecedented expressive possibilities in Munch’s work. New content creates a new vessel for itself.

Munch discovered printmaking around 1894 during his time in Berlin. Later in Paris, he learned to make woodcuts and developed a profound mastery of the medium. Not only did he often use the wood grain to materially embody his pantheistic worldview, but the grain remained visible in the prints, causing a portion of the landscape to become one with the work of art itself.

For works like Melancholy II, he devised an ingenious technique: after cutting the printing block into three sections and inking them separately in black, red, and blue, he reassembled the pieces and printed them on the paper. The line between the sections remains visible, showing that the woodcut was printed from three separate blocks. This technique not only facilitated the production of variations in different colors, but also emphasized the tripartite composition and intensified the feeling of isolation: the woman is separated from the land, the land is separated from the sea . . . or are they? The woman’s red dress looks like an anthropomorphic boulder with a gaping maw, echoing the undulating line of the coast. And so even in this image of separation, attraction, and loneliness, the seashore seems to move and almost magically resonate. A similar effect also appears in the printed variations of Two Human Beings. The Lonely Ones...

Different versions, all enigmatic, with a dark male figure...

... while the woman is illuminated on the side facing away from the light.

Edvard Munch: The Girls on the Bridge, 1902, Private collection

There were only old Fishermen in Town [...] the young men were all out at sea — and thus only old Wives and Women and Children were to be seen.

Some of Munch’s most famous motifs are women or girls on a bridge. He painted many versions and variations of the theme — such as this scene with the Norwegian village of Åsgårdstrand and the artist’s country house of Kiøsterud in the background. There is a hint of mystery about the girls; they seem to giggle and whisper. Most of all, they seem healthy and happy, at peace with each other and the shimmering evening mood. The view of the shore with houses is rare in Munch’s work. He is the master of the middle ground: there is little in the way of a foreground and almost never a background, giving his images a special intensity. This quality was also observed by Munch’s friend, the artist Max Liebermann, especially with the motif of the girls. Munch later reported that according to Liebermann, “this is my best picture.”

Edvard Munch: Girls on the Pier, um 1904, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Munch’s painting of these girls made the town of Åsgårdstrand world famous.

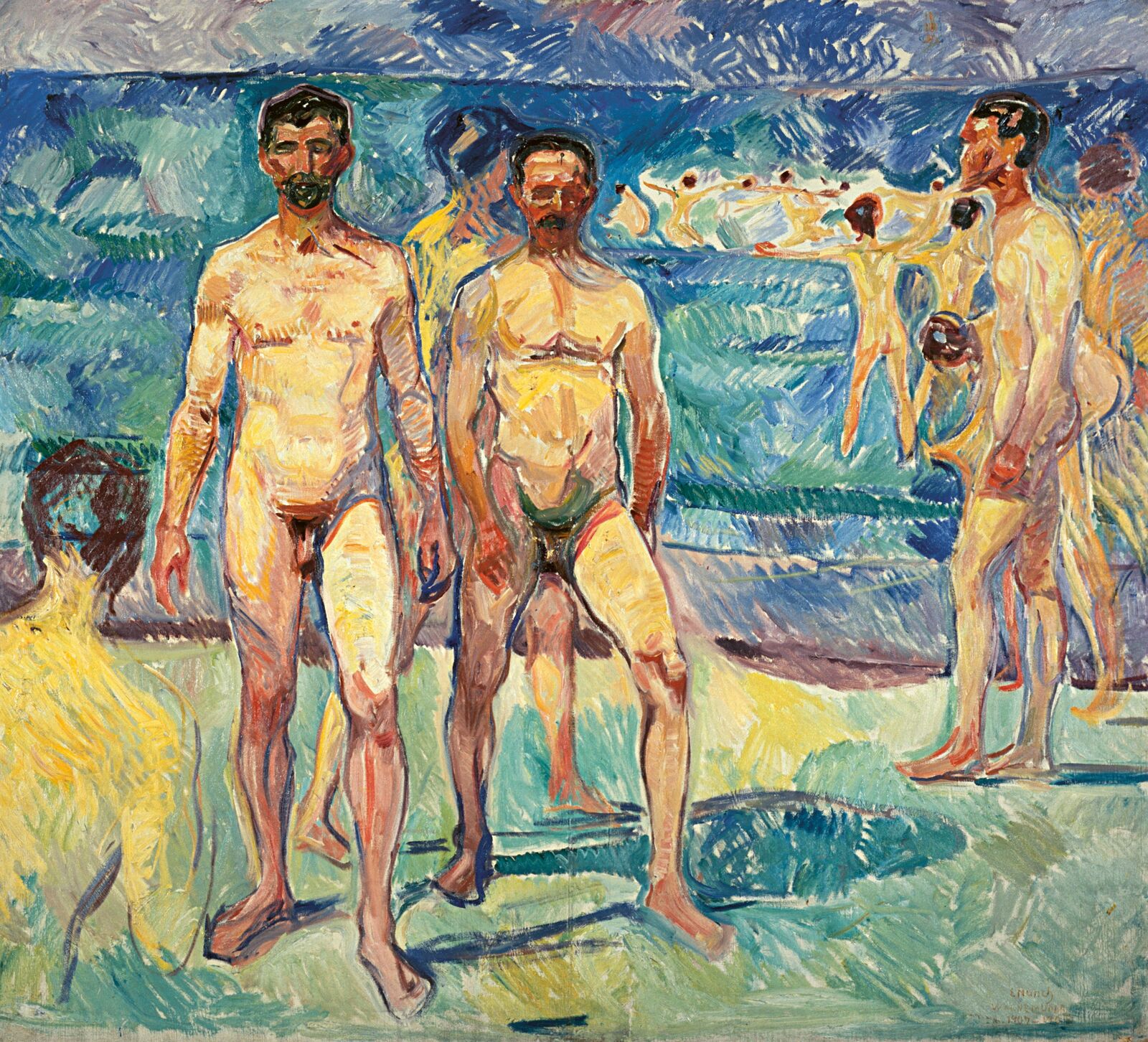

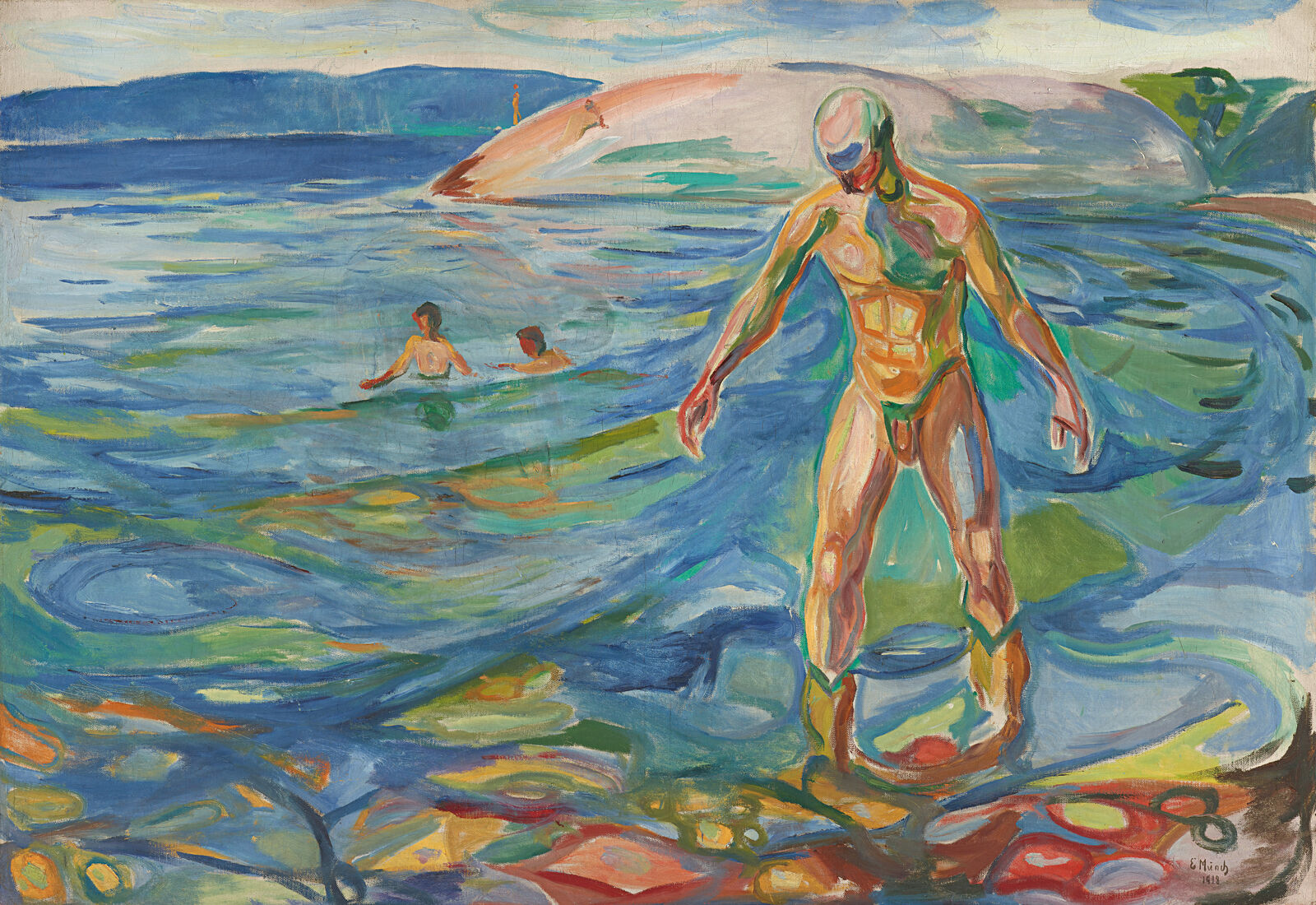

In 1907 and 1908, Munch painted multiple pictures of men on the beach at the Baltic seaside resort of Warnemünde. For him, their stark-naked muscle-flexing was a symbol of vitality; he painted Bathing Men directly on location, as we know from photographs showing Munch working at his easel on the beach.

Ten years later, he painted another Bathing Man, probably near Hvitsten, where he owned a house from 1910 on. There he also discovered sunbathers as a motif, symbolizing a kind of energetic connection between human beings and light.

Health and physical vitality were recurring themes for Munch, especially after his recovery from alcoholism in 1908.

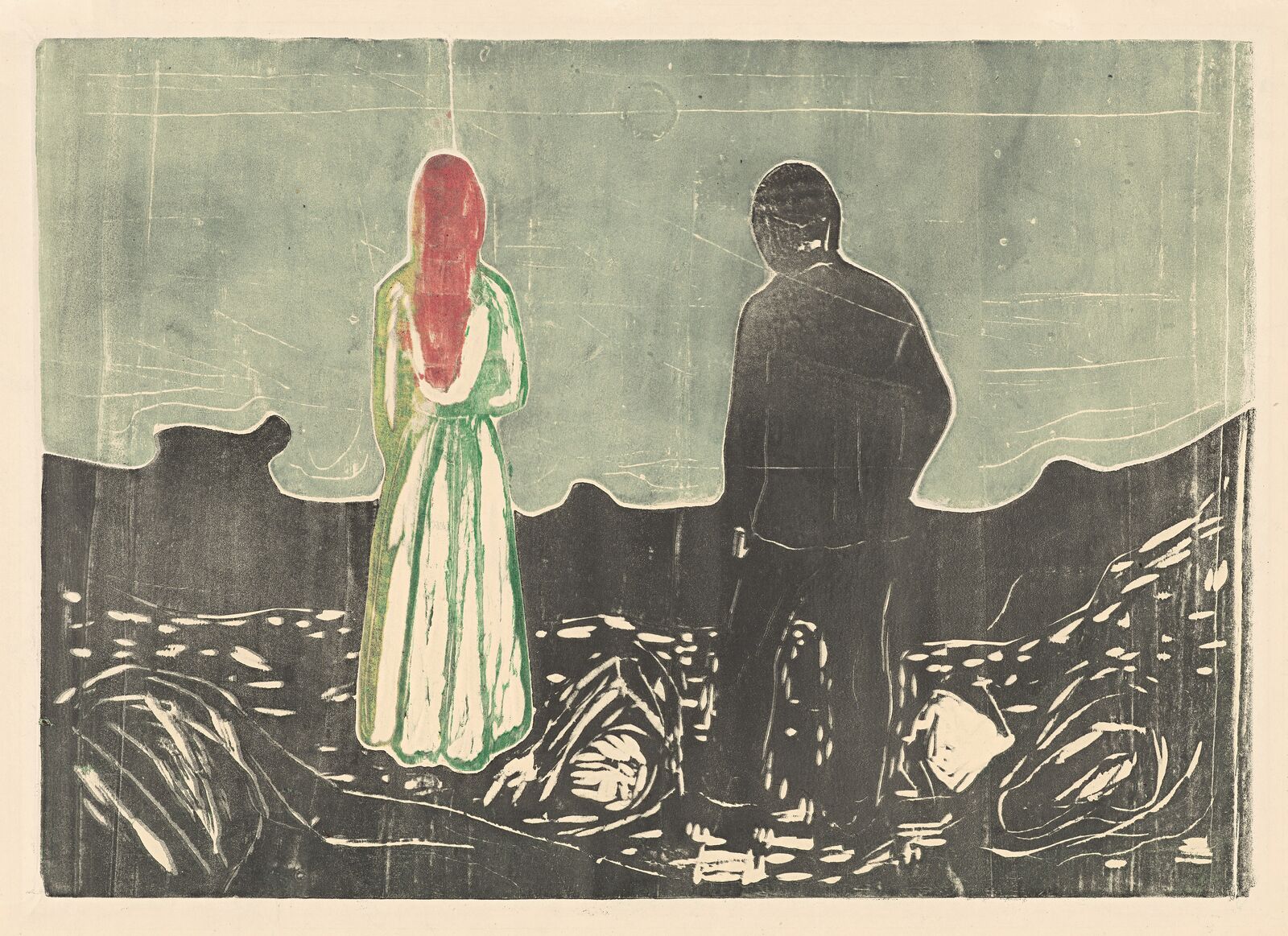

The painting Waves Against the Shore was also created in Hvitsten — a dynamic study of the union of sea and land, water and light. The expressionistic brushwork recalls the esoteric images of the Swedish painter Hilma af Klint.

Edvard Munch: Waves against the Shore, 1911-12, Munchmuseet, Oslo

Two of Munch’s favorite motifs: undulating coastlines and reflections of light.

In the ocean paintings from Warnemünde, however, Munch adopted a completely different approach. Seascape is a vivisection of greenish-blue water with the yellow sand shimmering through. In Waves, both we and the painter are hurled headlong into the tumult of the sea: tossed by the surf, we can hardly tell which way is up.

Edvard Munch: Seascape from Warnemünde, 1907-08, Munchmuseet, Oslo

An exercise in aesthetic oceanography: how green is the blue, how distant is the horizon?

Edvard Munch: Waves, 1908, Munchmuseet, Oslo

At the center of Munch’s Sun is the all-unifying power of light.

Edvard Munch: The Sun, 1910-13, Munchmuseet, Oslo

... toward the light, toward the sun, toward revelation.

Edvard Munch: The Sun, 1910-13, Munchmuseet, Oslo

At the center of Munch’s Sun is the all-unifying power of light.

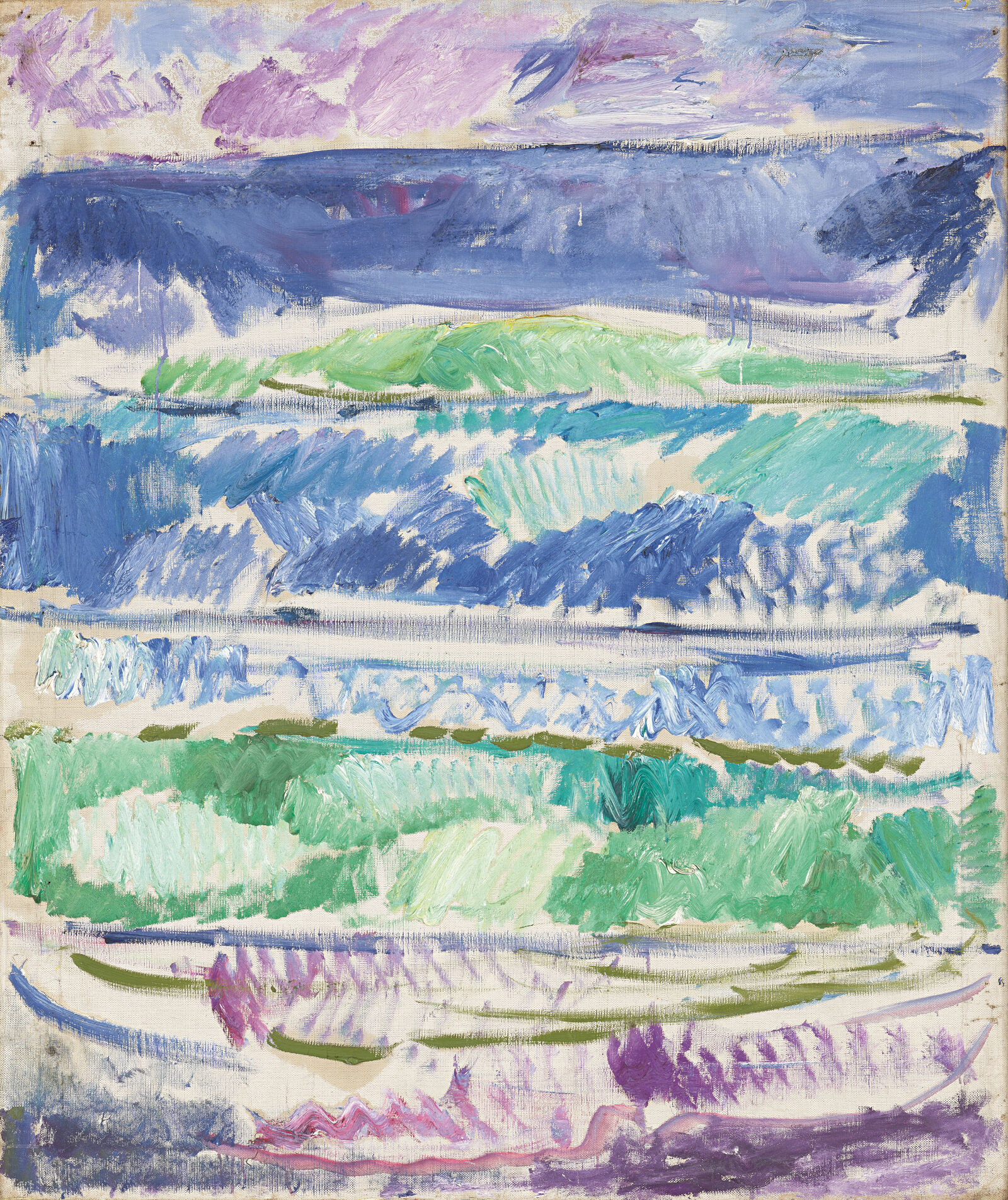

The breadth of Munch’s range as an artist — or, as we could almost say, his inner conflict — becomes especially clear in The Scream and The Sun. Both works embody the interpenetration of figure and landscape, earth and cosmos. Yet while the figure in The Scream is clearly experiencing existential distress, the celestial body in The Sun is so radiant and freely painted that its rays seem to pass beyond the work to illuminate both painter and viewer. In Munch’s art, nature itself becomes the locus of the human drama and at the same time a creative plumbline, a cycle of death and rebirth to which we are called to surrender.

Edvard Munch: The Scream, 1895, Private collection

Even without the dark red color of the painted version, The Scream is an icon of modernity — and of terror.

The earth and the stones longed to mix with the air, and human beings and animals and trees were created and air turned into water and earth became air.

Edvard Munch: The Storm, 1893, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. Irgens Larsen and acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange) and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Funds, 1974

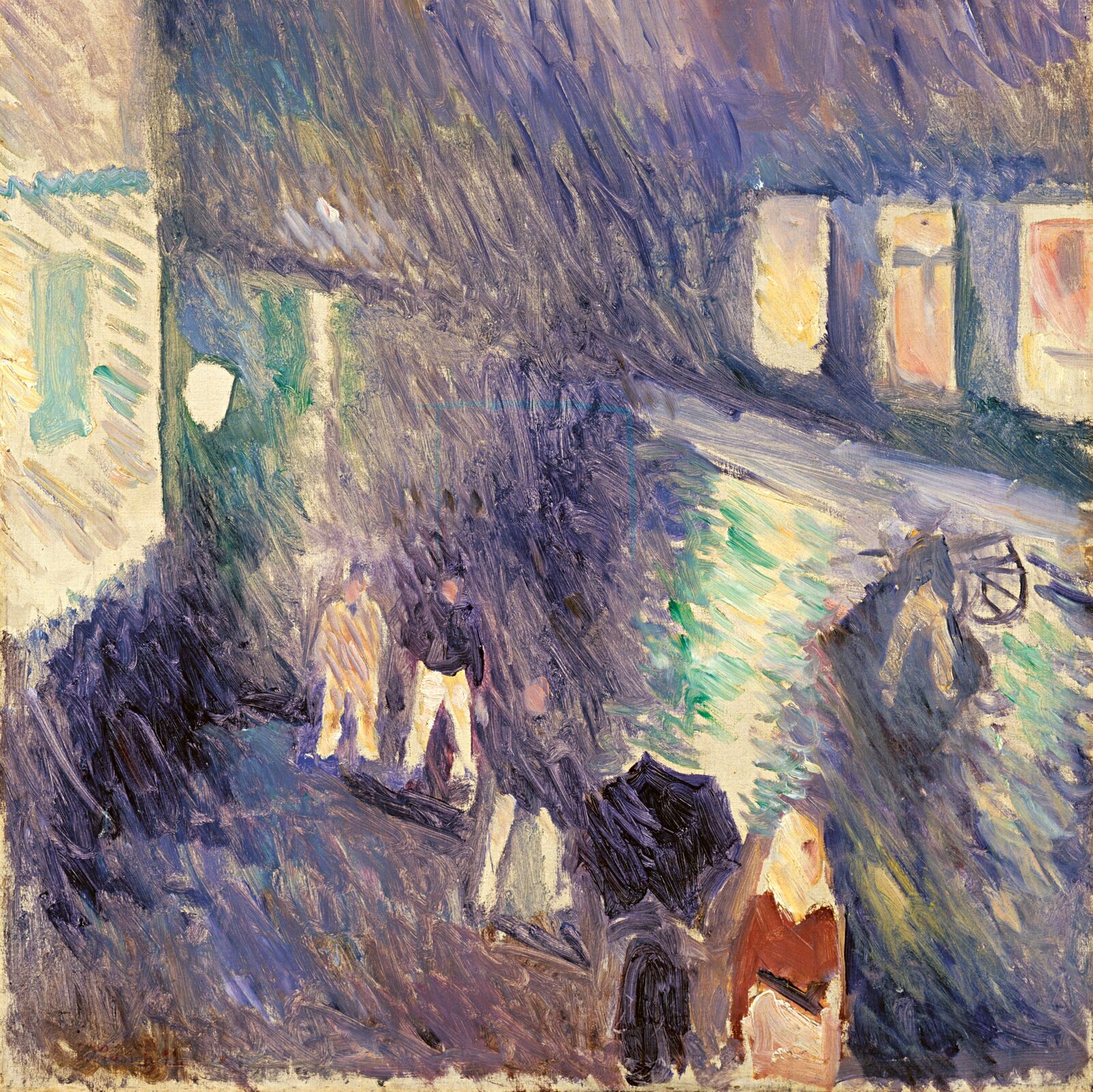

Anxiety over climate change existed even in Munch’s time — although it was not a fear of global warming, but rather of colder temperatures in the form of a new ice age. Yet Munch’s paintings show little evidence of this fear, though he does acknowledge the power of the elements in works like The Storm or Autumn Rain. In the latter, he translates the pelting rain into brushstrokes that seem to wash the people from the street.

Edvard Munch: Autumn Rain, 1892, Christen Sveaas Art Collection

The brushwork dominates the painting: Van Gogh would have approved.

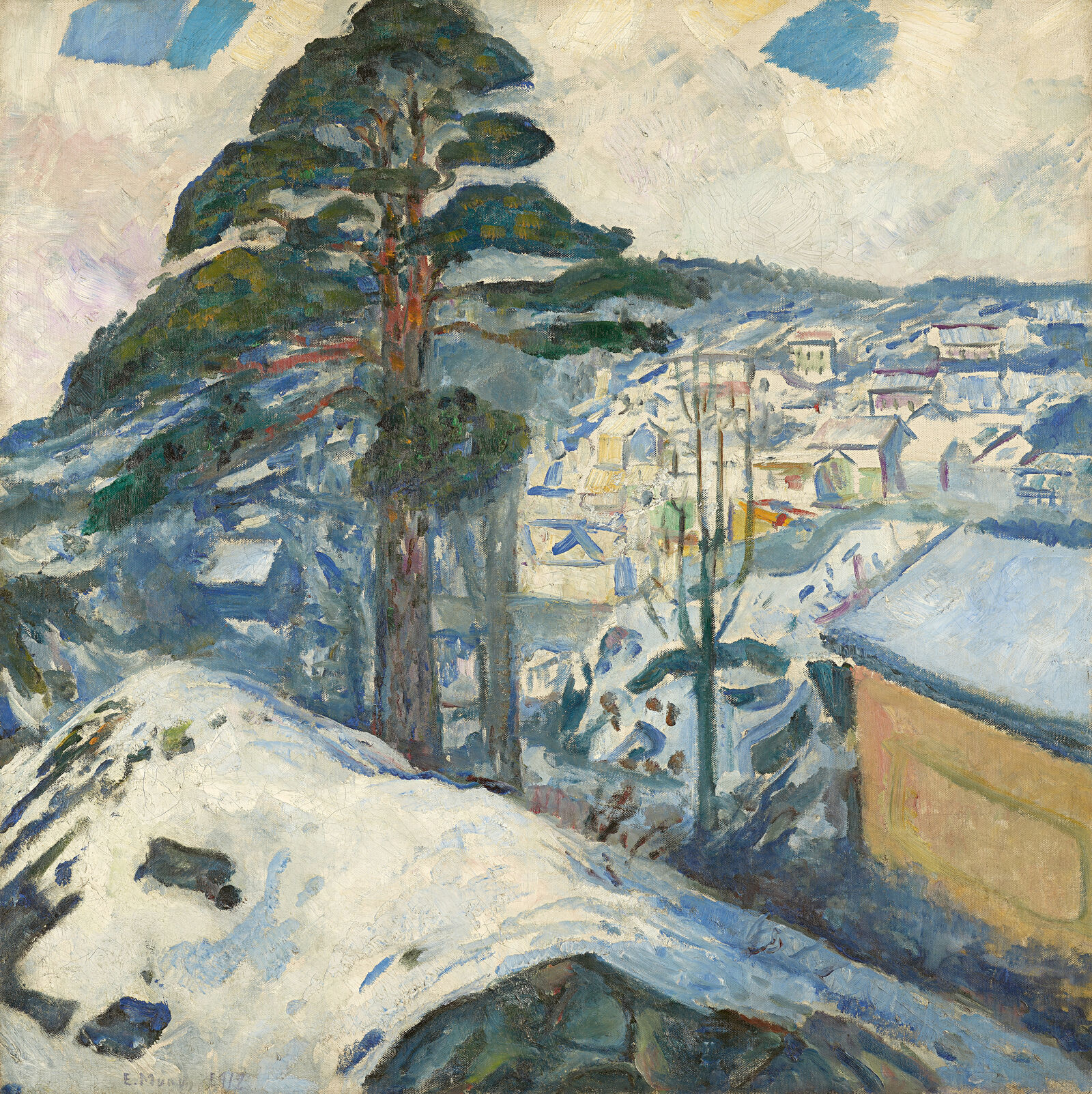

Munch loved to paint the world covered in snow — sometimes fairytale-like, sometimes more realistically, as in Winter in Kragerø. He was fascinated by the thawing of the snow, the transition from ice to water. He approached it lyrically and metaphorically in works like Snow Landscape in Thuringia. He once noted: “the streams gushed—the roofs dripped—sparkling liquid pearls — The Earth softened.”

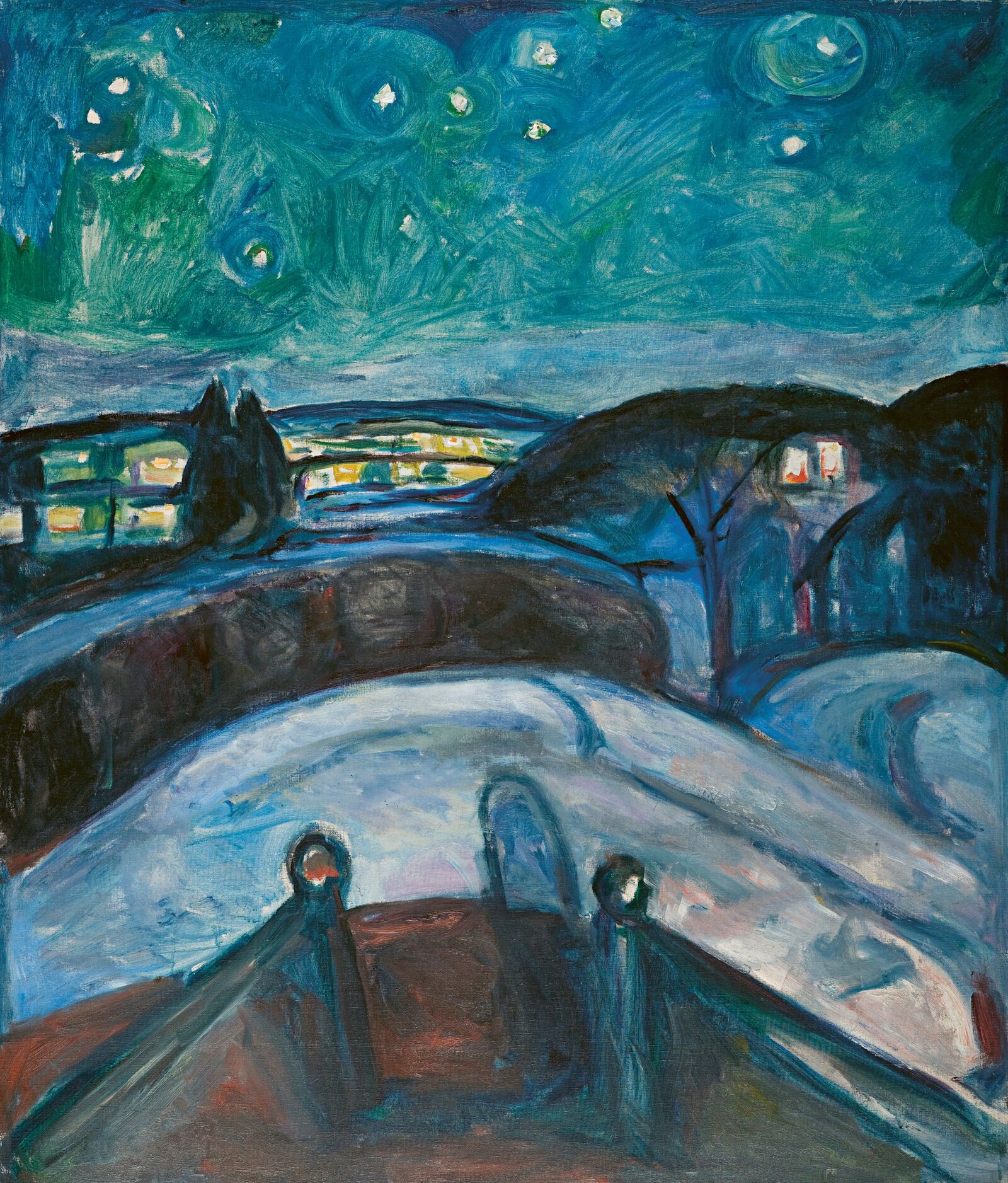

Munch’s mysterious, almost dream-like images of Nordic winter nights have a special intensity. Works like Starry Night are so atmospheric we can almost hear the crunch of the snow.

It’s hard to imagine a more powerful image of silent, wintry fields.

A sculpture of Munch looking toward the sea now stands in Kragerø.

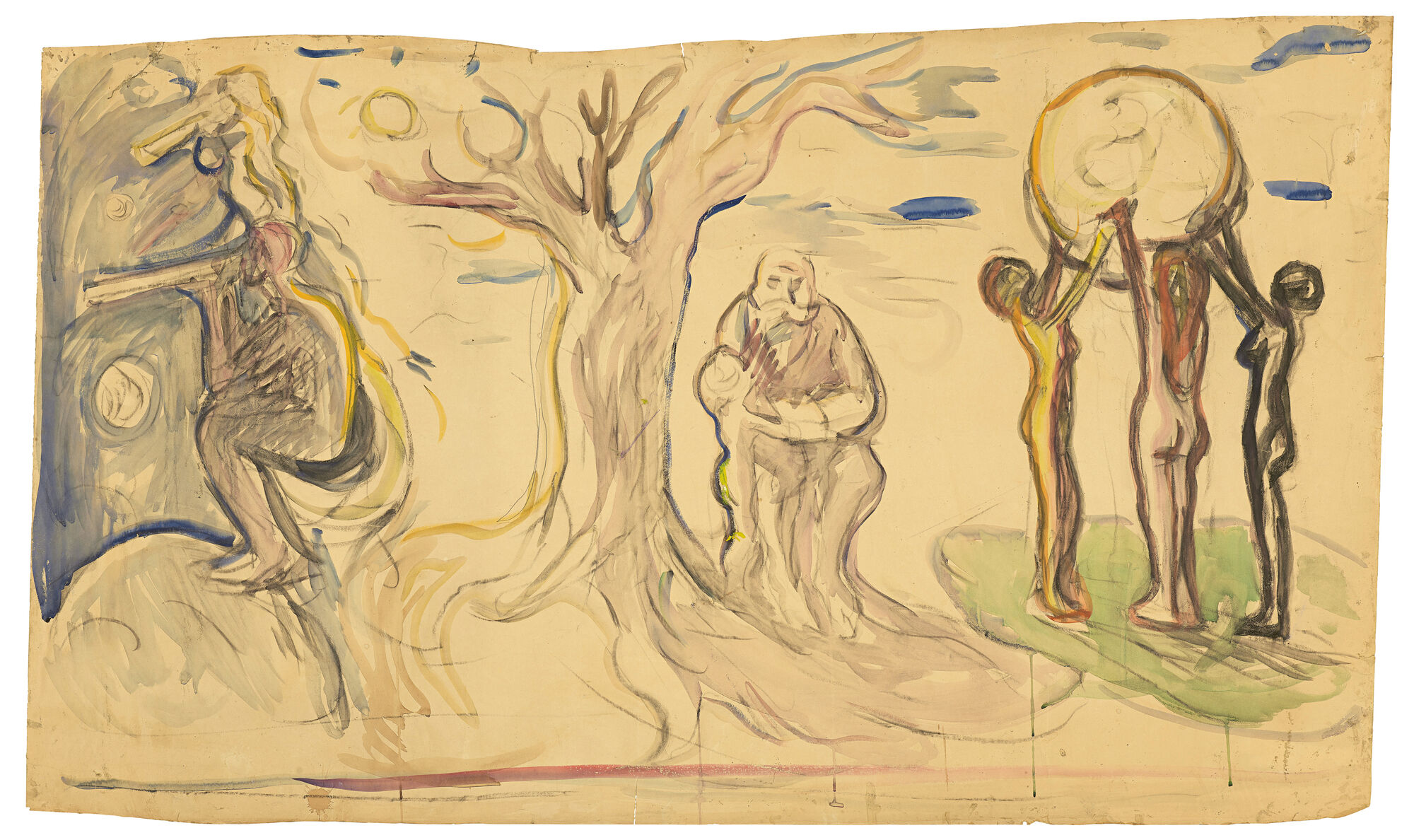

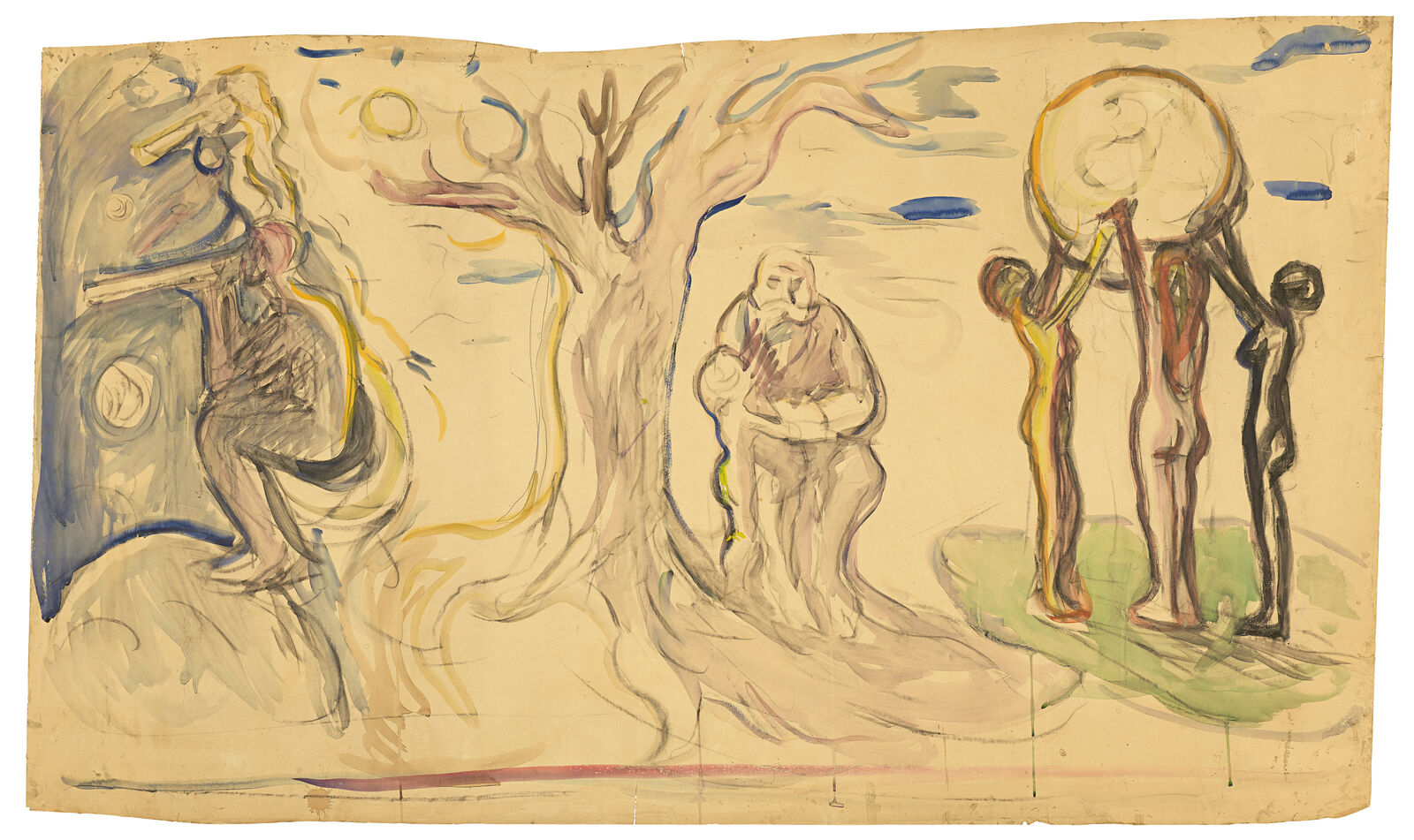

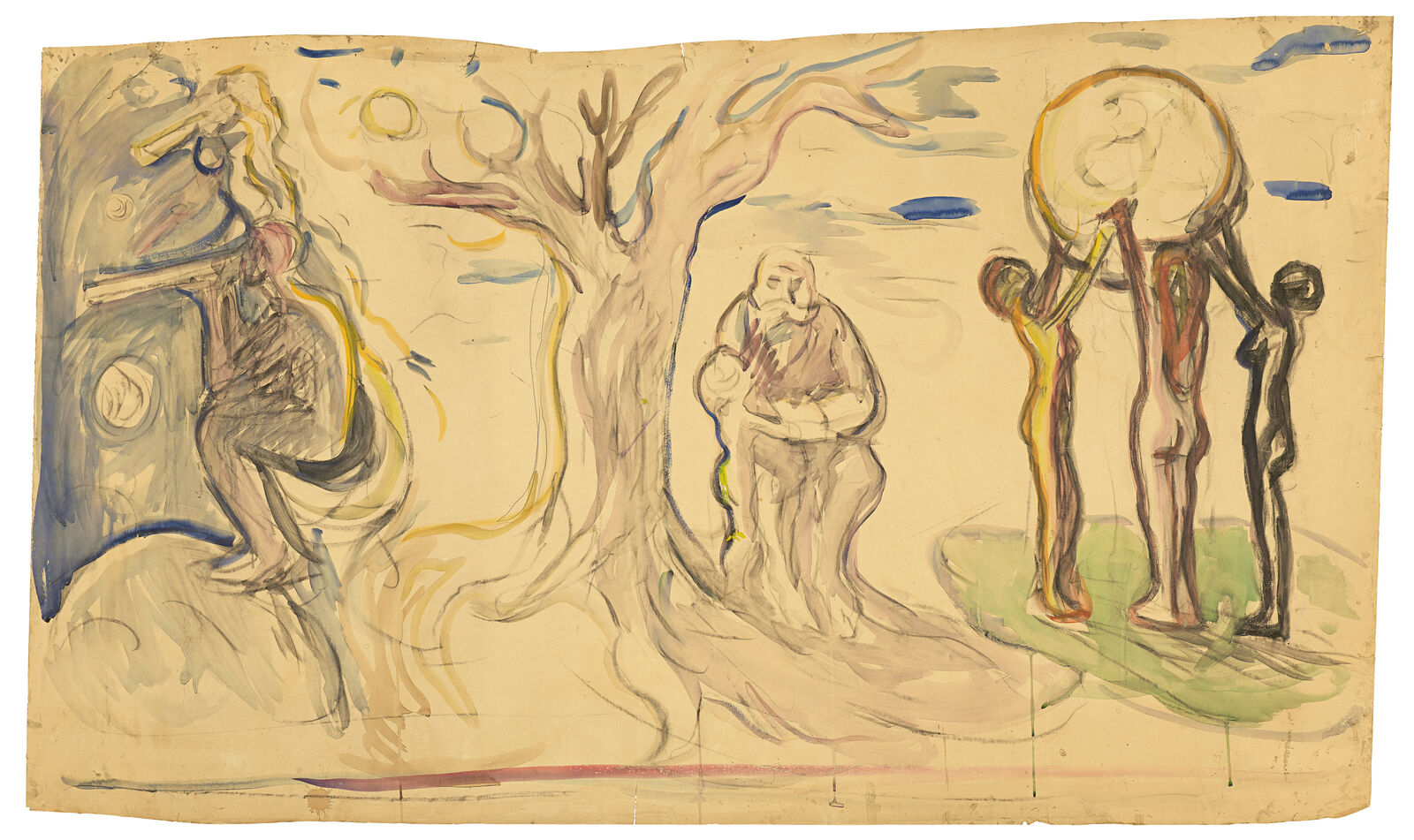

Edvard Munch: Astronomy, History and Geography, 1909, Munchmuseet, Oslo

Munch was a passionate reader; after his death in 1944, around 1,500 books were found in his house in Ekely. The breadth of his thought and study is manifested not only in allegorical images like Astronomy, History and Geography, but also in the wide range of his reading. His library included books on fertilizer, Norwegian flora, and Einstein’s theory of relativity, along with K. G. Dobler’s Ein neues Weltall (A New Universe), Knut Hamsun’s Markens Grøde (Growth of the Soil), and works by Munch’s writer friend Max Dauthendey, such as his volume of poetry Die schwarze Sonne (The Black Sun).

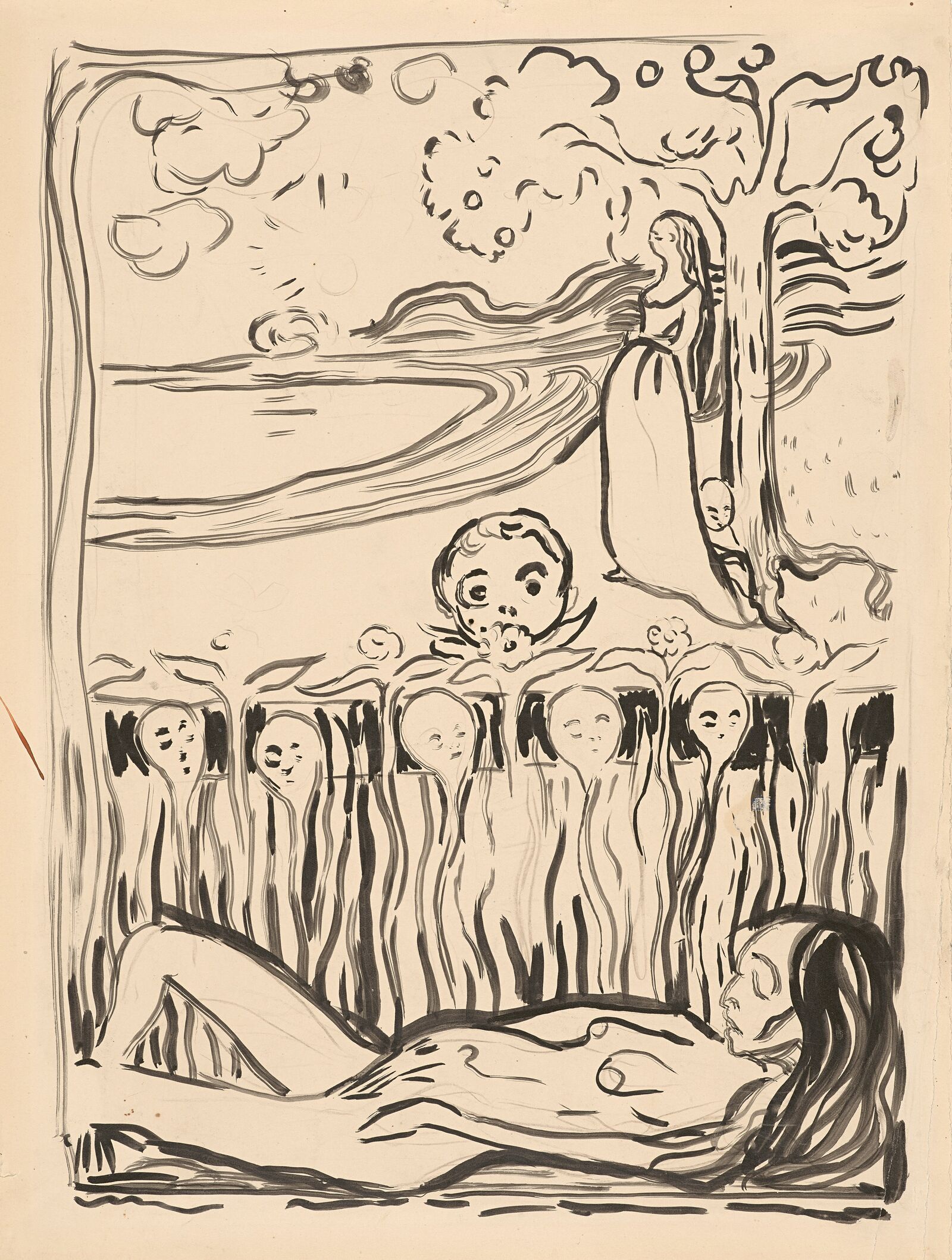

On the one hand, Munch’s art almost always conveys something of the desperation of The Scream, a godforsaken brooding in the spirit of Friedrich Nietzsche, whom the artist considered one of the greatest philosophers of all time and whose portrait he painted posthumously. On the other, his work was also dominated by a positive spiritualism and connectedness with nature, at times mythical, at times biological and philosophical. In the drawing Metabolism (Life and Death), plants grow from the body of a dead woman. Twenty years later, he varied the theme: in Metabolism (1916), the cycle of life is permeated and transformed by the broad yellow rays of the sun.

Edvard Munch: Metabolism (Life and Death), 1896, Munchmuseet, Oslo

Though Munch was haunted by the fear of death, he came to terms with it philosophically.

For Munch, to be integrated into the cycle of nature was a consolation, although in this regard he held some unusual ideas. For him, the universe “belongs to a higher, more powerful human being,” which at the same time is “made up by the same chemical compounds as we are, just as the earth, the sun, the solar system” — concepts taken from Dobler’s Ein neues Weltall of 1892. And then there was the notion of crystallization:

What I wanted to indicate is that death is a transition into new life — The dead body is transformed into crystalline form.

Even during his days of alcoholic excess at the Berlin tavern “Zum schwarzen Ferkel” (The Black Piglet), Munch had attempted his first images of a crystallization that could awaken minerals to life — in grandiose manner in the charcoal drawing Worlds are Within Us, followed somewhat later by In the Land of Crystals and Funeral March. According to Munch, “Everything is Life and Movement — The spark of Life is found even in the Earth’s Bedrock — The Crystals – .”

Edvard Munch: Funeral March, 1897, Munchmuseet, Oslo

Art is the human urge for crystallization. Nature is the eternal great realm from which art takes sustenance.

Munch’s ideas recall the natural philosophy of Ernst Haeckel, whom he may have encountered on his visits to Thuringia. There, he did meet the art historian Botho Graef, who aptly observed that Munch did not copy nature, but rather clarified it: “If his art appears to deviate from reality, […] it never veers away from nature. On the contrary, it portrays nature’s regularity in a cleaner and purer way.”

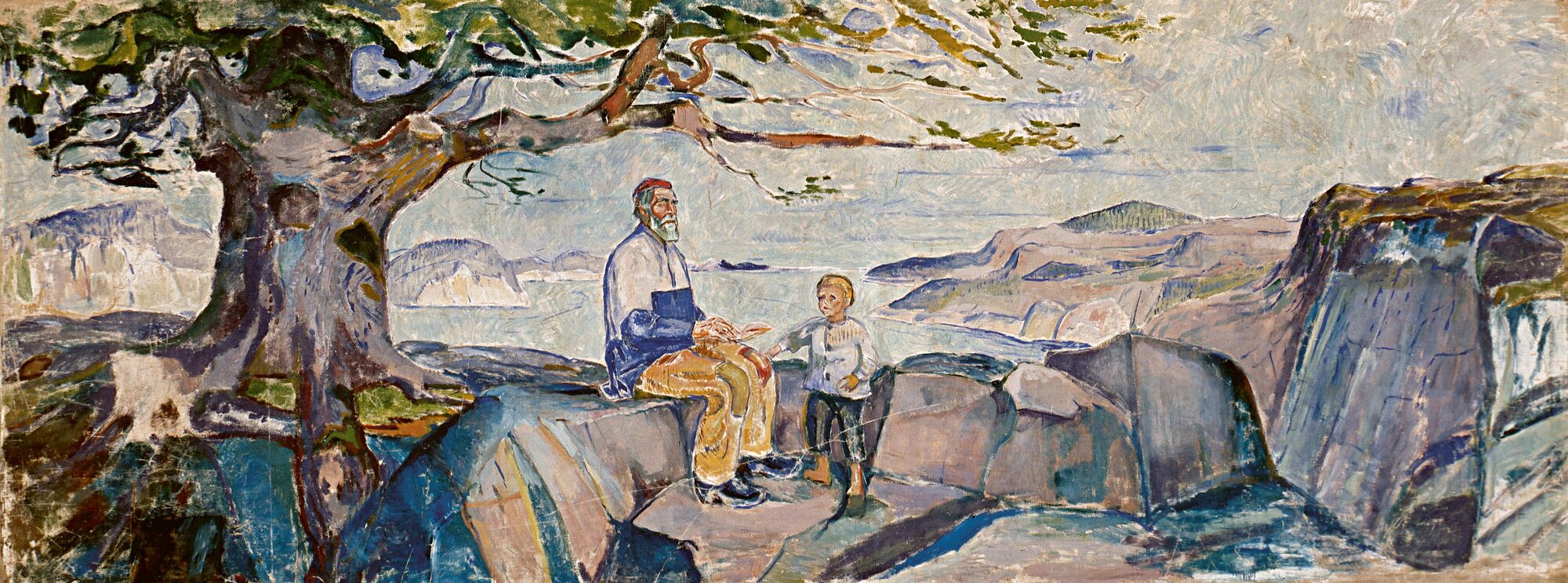

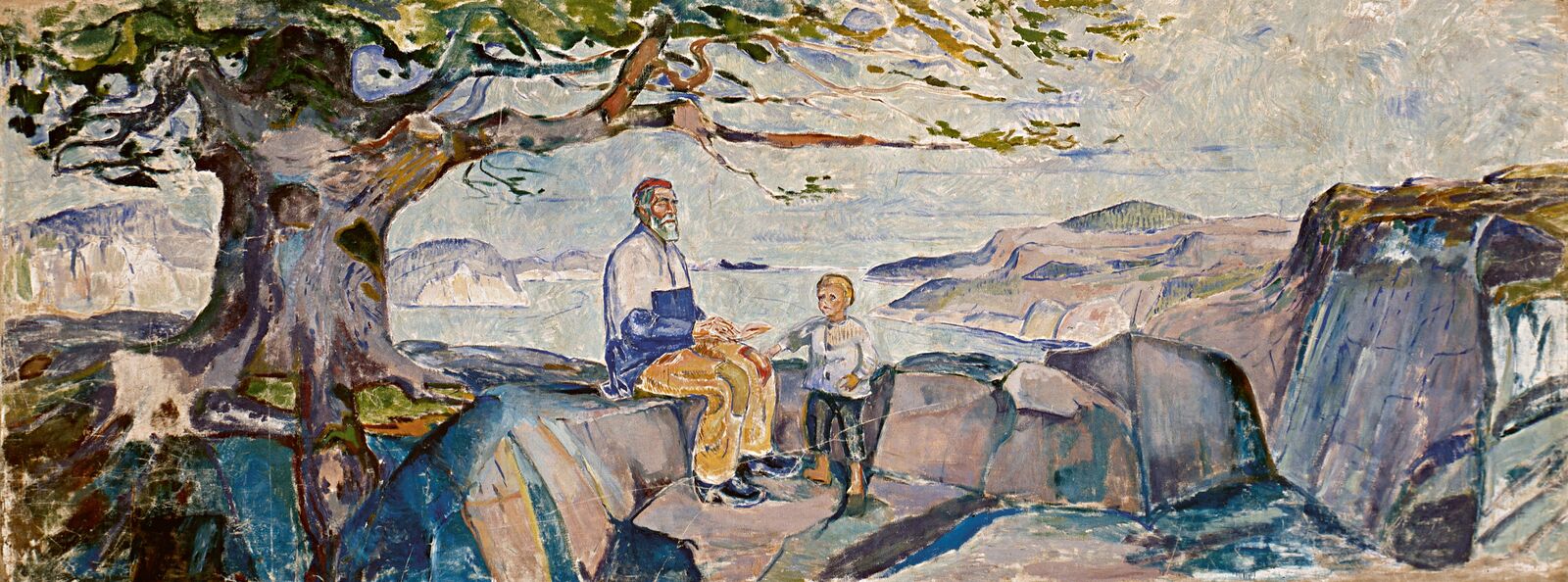

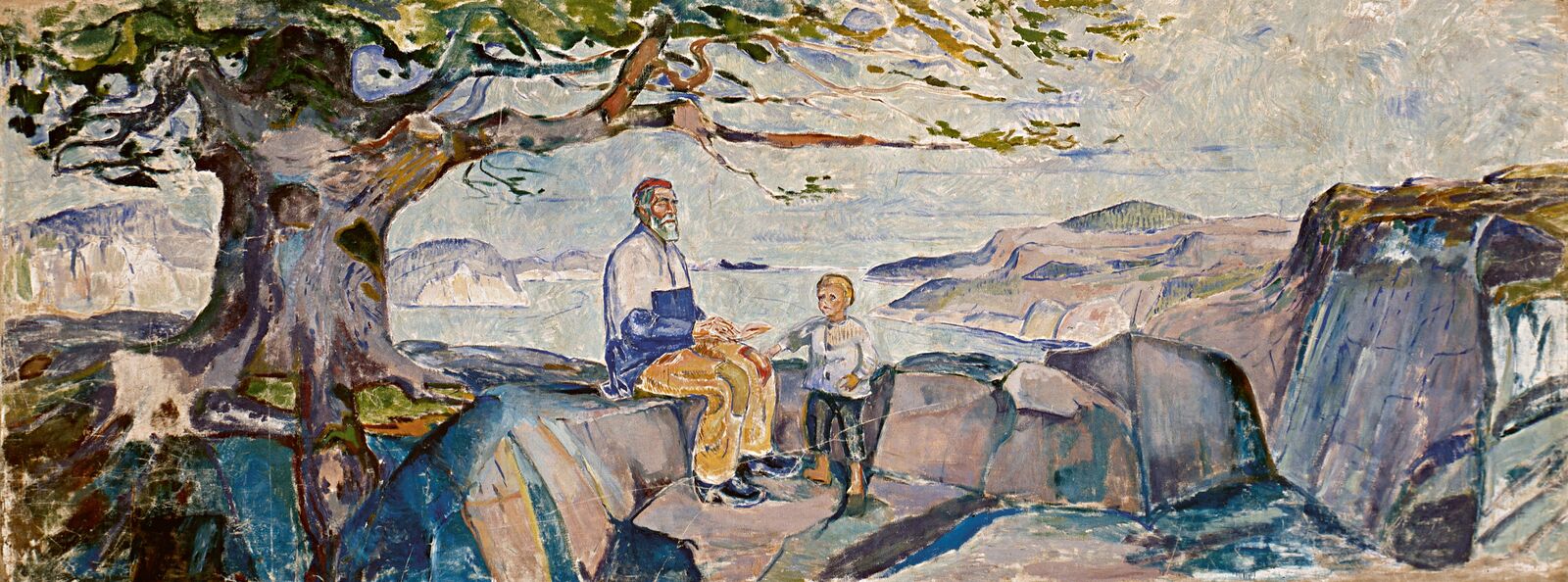

Edvard Munch: History, 1912/13, Munchmuseet, Oslo

The monumental wall paintings for the Aula of the University of Oslo, created at the midpoint of Munch’s life, are a culmination of his art and thought. Here we find the idea of crystallization as well as the love of rural life and union with nature. Even loneliness and the search for love still resonate here, although they are transformed. An especially powerful work is the wall painting The Sun with its two accompanying panels Women Turned Towards the Sun and Men Turned Towards the Sun.

Edvard Munch: The Sun, 1912-13, Munchmuseet, Oslo

In Munch’s design for the University of Oslo, the colors of the sun glow with even greater intensity than in earlier versions.

The solar star appears as an explosion of color above an abstracted fjord landscape, hurling its rays through the cosmos until they reach the humans on the side panels — women on the left, men on the right, separated only at first glance. The power of the light unites them in an arrangement that almost recalls the composition of Fertility: in both works, the connection between the figures and between the sexes is established by nature — by the sun and a tree.

Edvard Munch: Women Turned Towards the Sun, 1912-13, Munchmuseet, Oslo

The women bathe in the light ...

Edvard Munch: Men Turned Towards the Sun, 1912-13, Munchmuseet, Oslo

... as do the men.

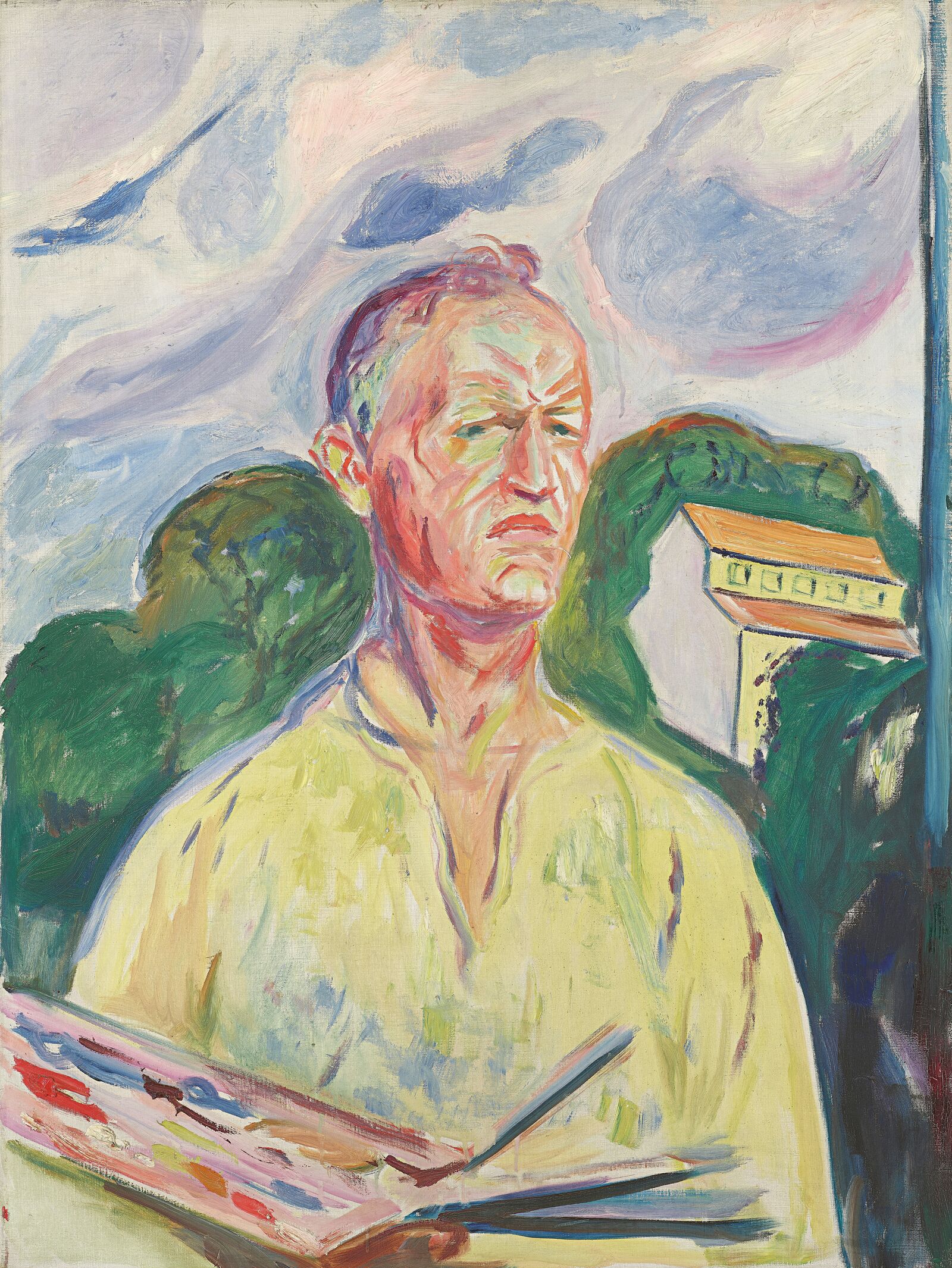

This organic, mythical unity defines the art of Edvard Munch through and through. For the first time, the exhibition Trembling Earth shows him to be a hero not only of alienated modernism, but also of nature. In his Self-Portrait with Palette of 1924, we see it again: like the treetops, Munch’s head towers up into the blue sky.

Edvard Munch: Self Portrait with Palette, 1926, Private collection

Munch paints himself as part of nature.