Impressionism

In Paris, the young painters Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley joined forces and revolutionized art with landscapes bathed in light. In 1874 they became known as “Impressionists,” capturing fleeting sensations in the open air. Their paintings, focused on momentary impressions, still fascinate us today.

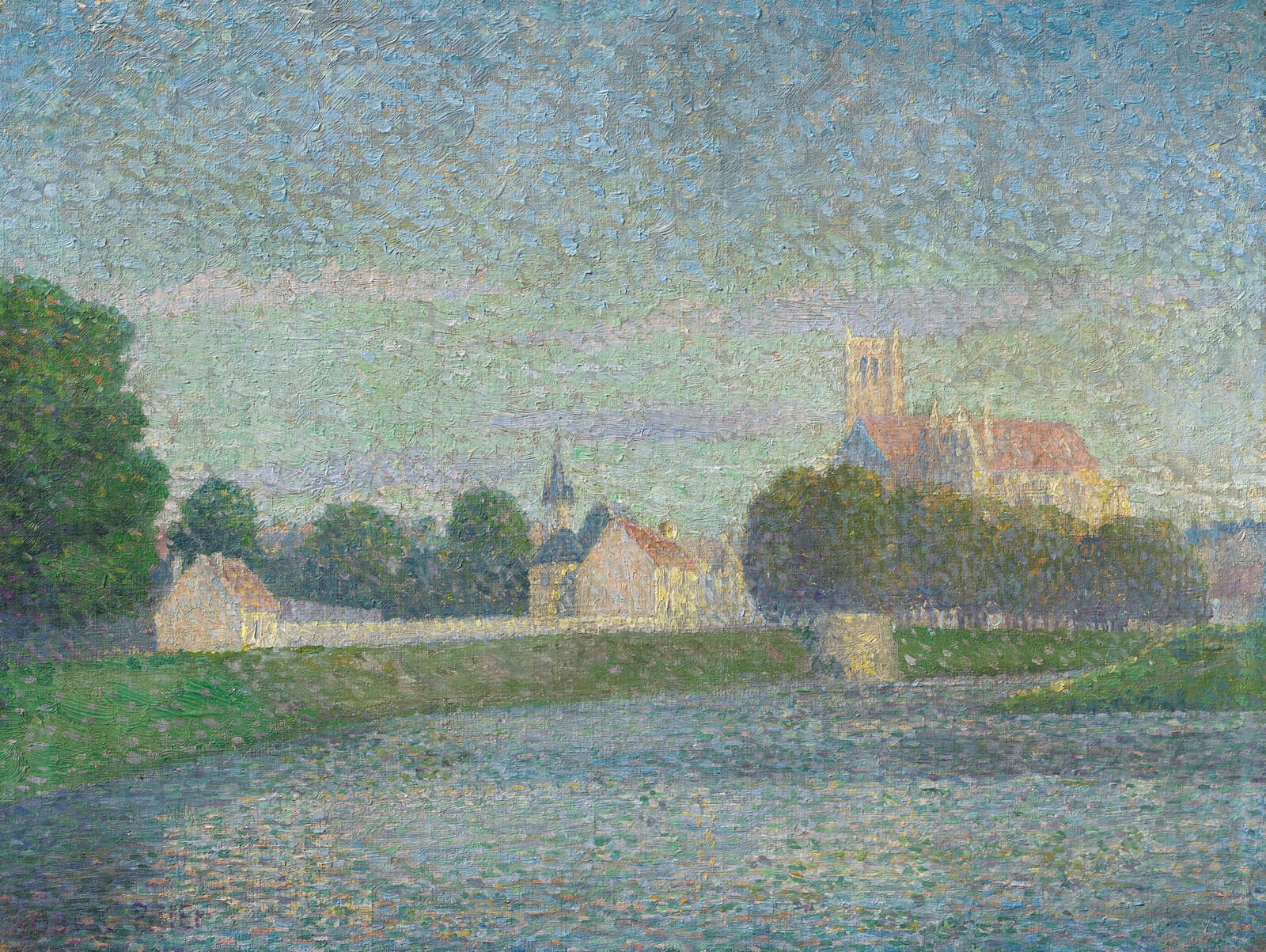

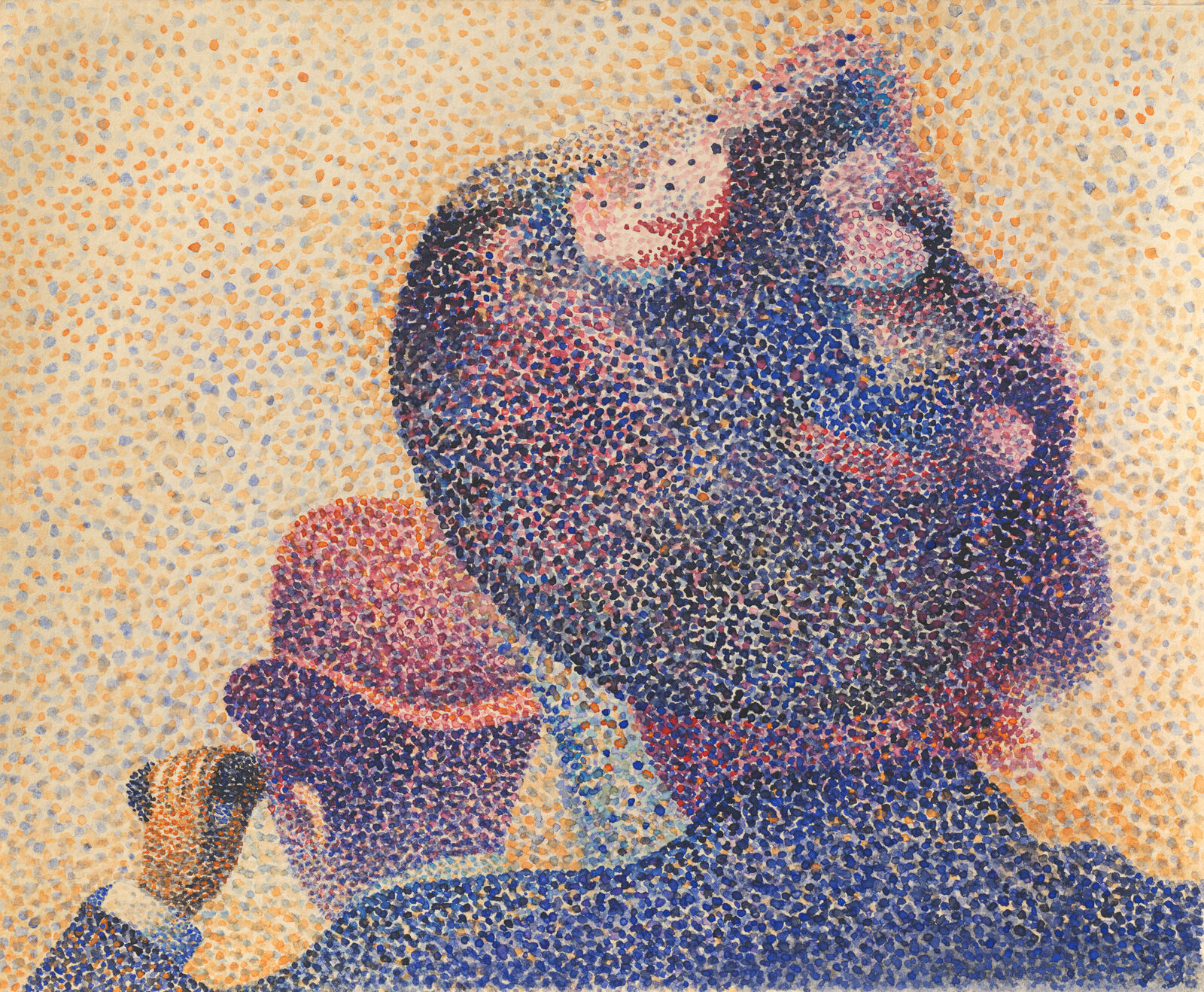

The Neo-Impressionist painters Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross also pursued the liberation of color in their landscapes, and the same quest informed the brilliantly colored compositions of the early 20th-century Fauves. The paintings of the Impressionists, Neo-Impressionists, and Fauves evoke the sensory experience of nature through light and color: ever-new and ever-changing.

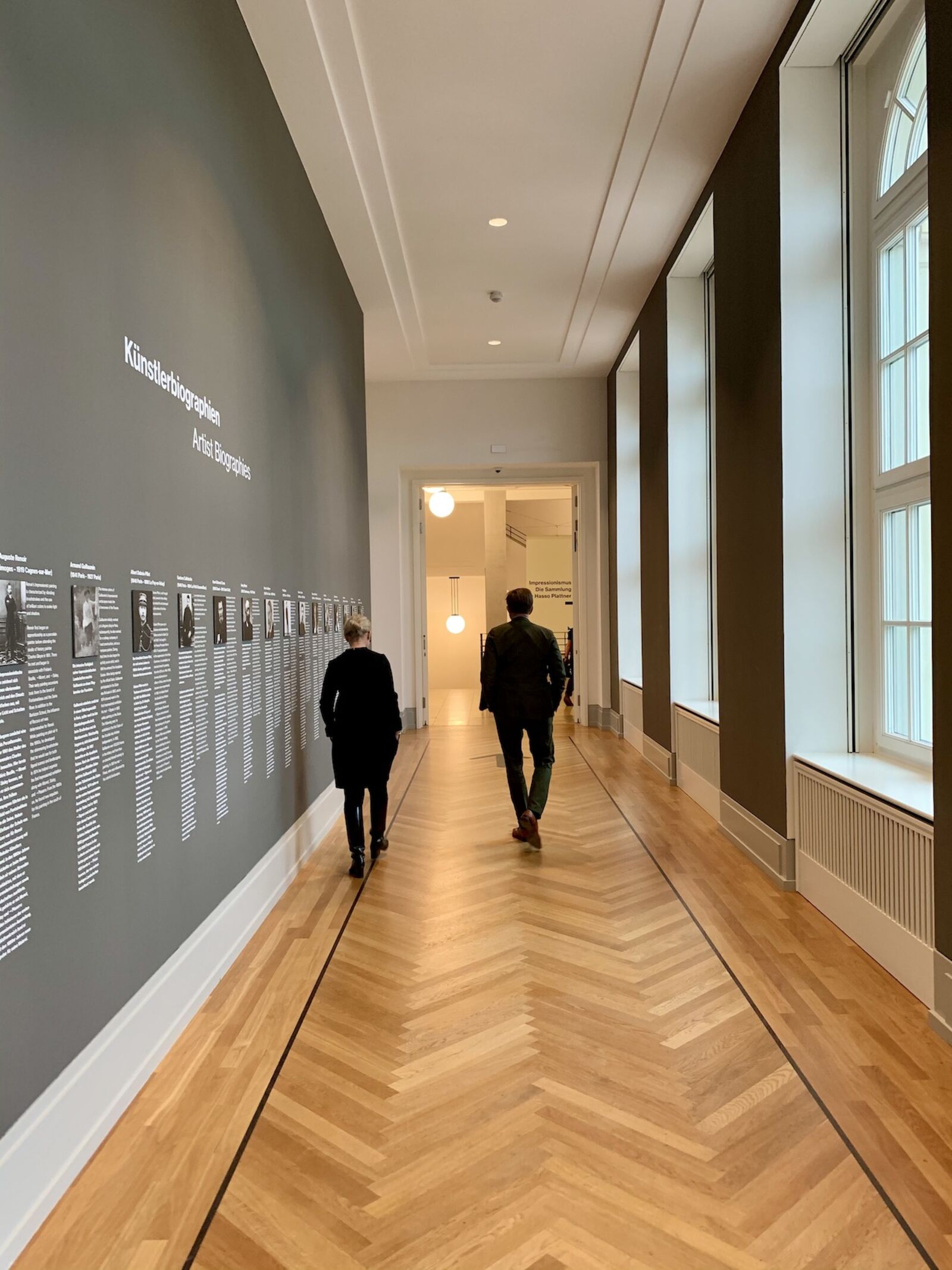

With 115 Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, the Museum Barberini houses the collection of museum founder Hasso Plattner. The 40 paintings by Monet form the largest collection of the artist’s work in Europe outside of France.

The presentation brings to life the entire thematic spectrum and artistic impact of Impressionism. In this Barberini Prolog, you’ll discover three generations of artists who often worked together, traveled to the same places, and inspired each other, giving rise to one of the most fascinating epochs in modern painting.

It is true that I live only through my eyes. From morning to evening I wander through forest and field, over rocks … in search of pure colors …

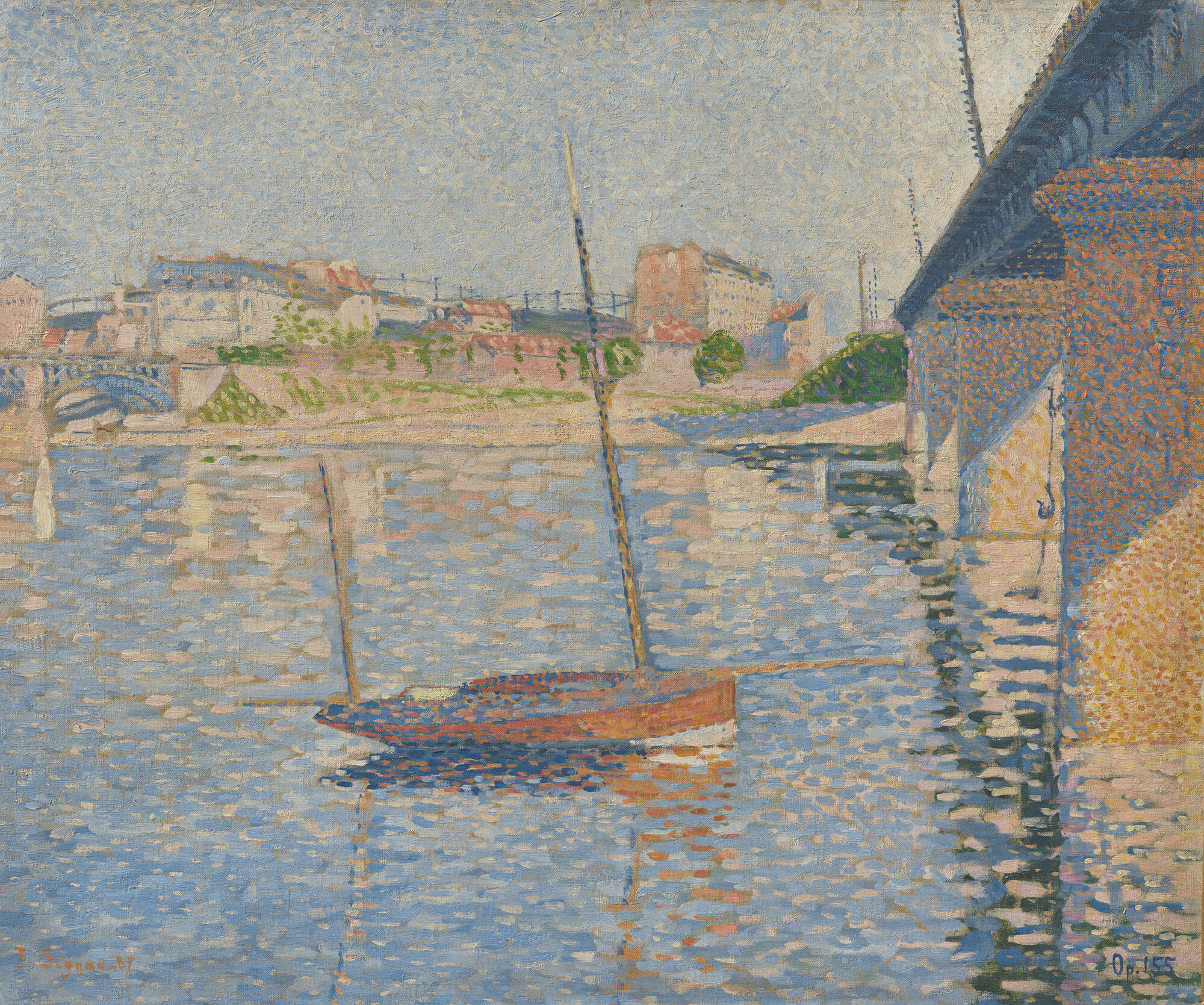

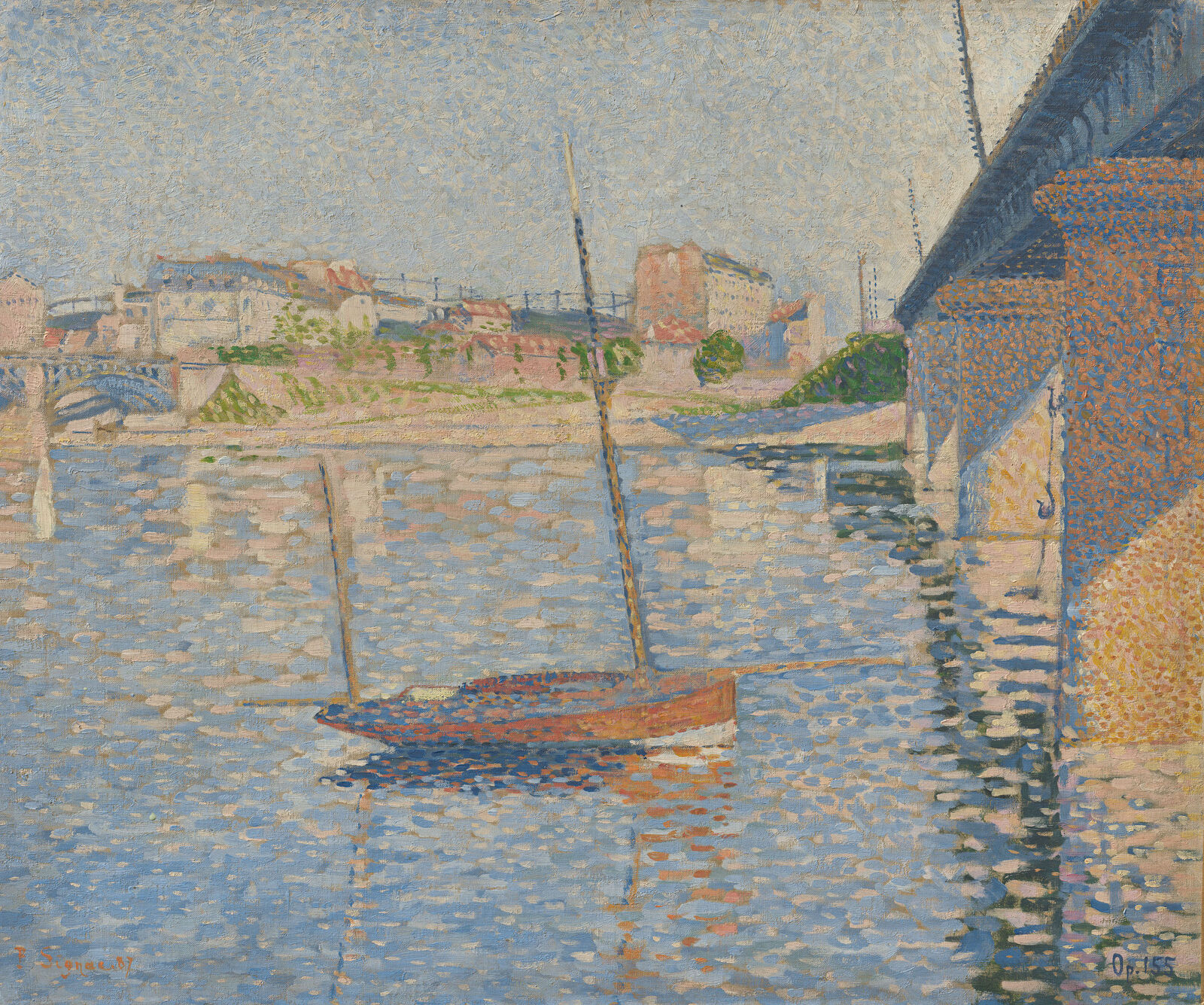

Paul Signac: Clipper, 1887

Hasso Plattner Collection

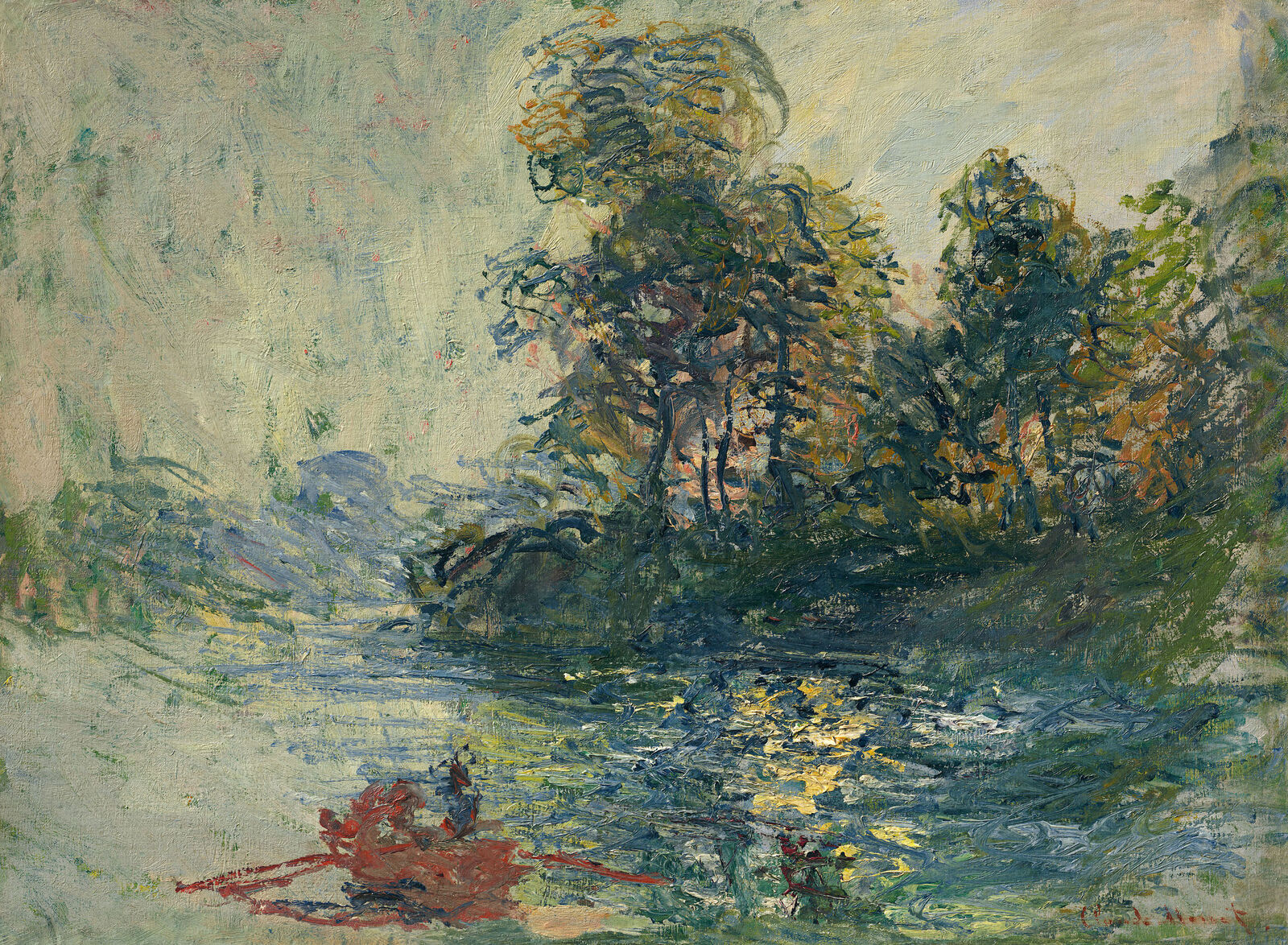

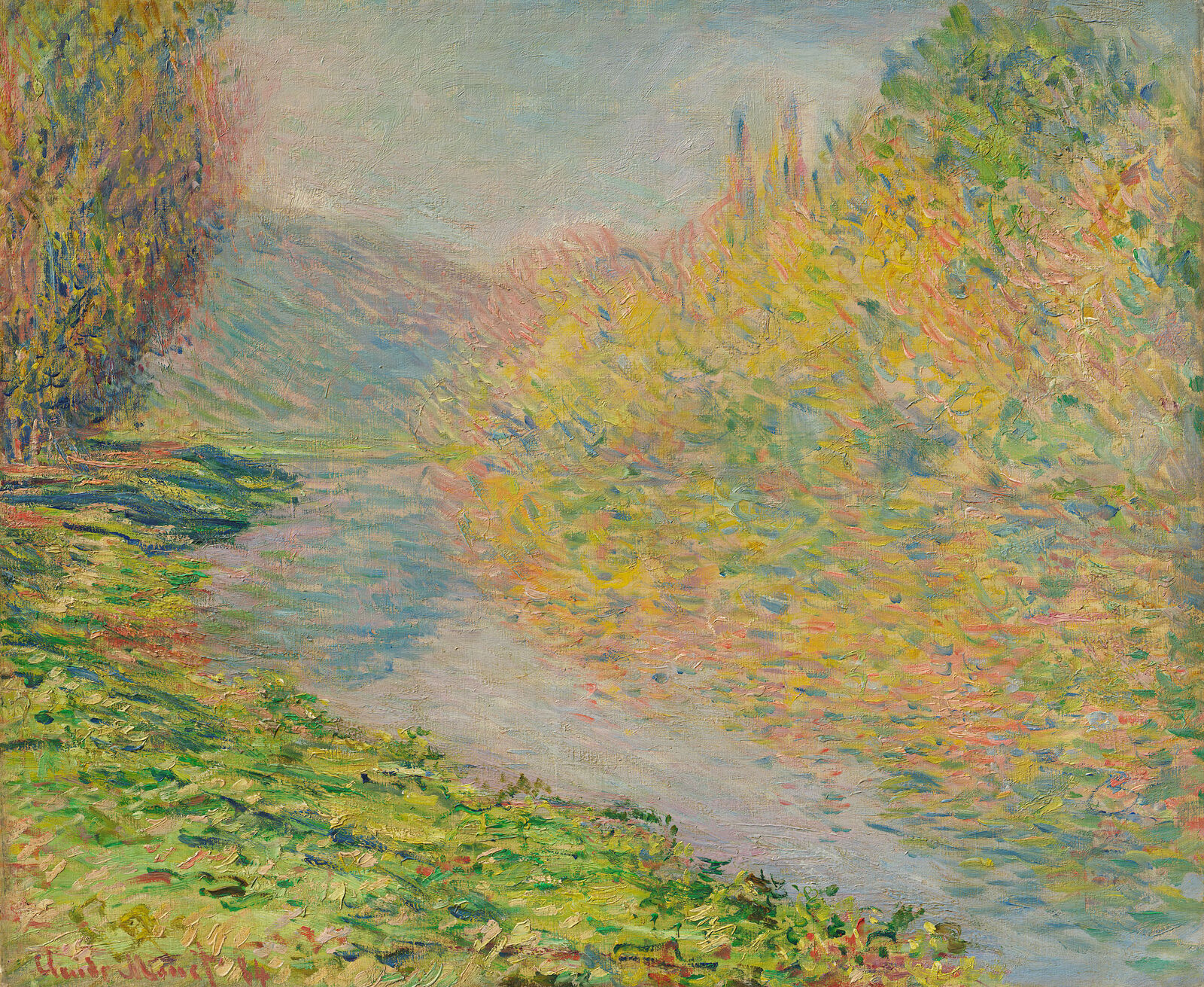

The Impressionists developed their motifs in the landscapes along the Seine. Working in the open air, they concentrated fully on the here and now, rejecting all anecdotal elements of earlier landscape painting.

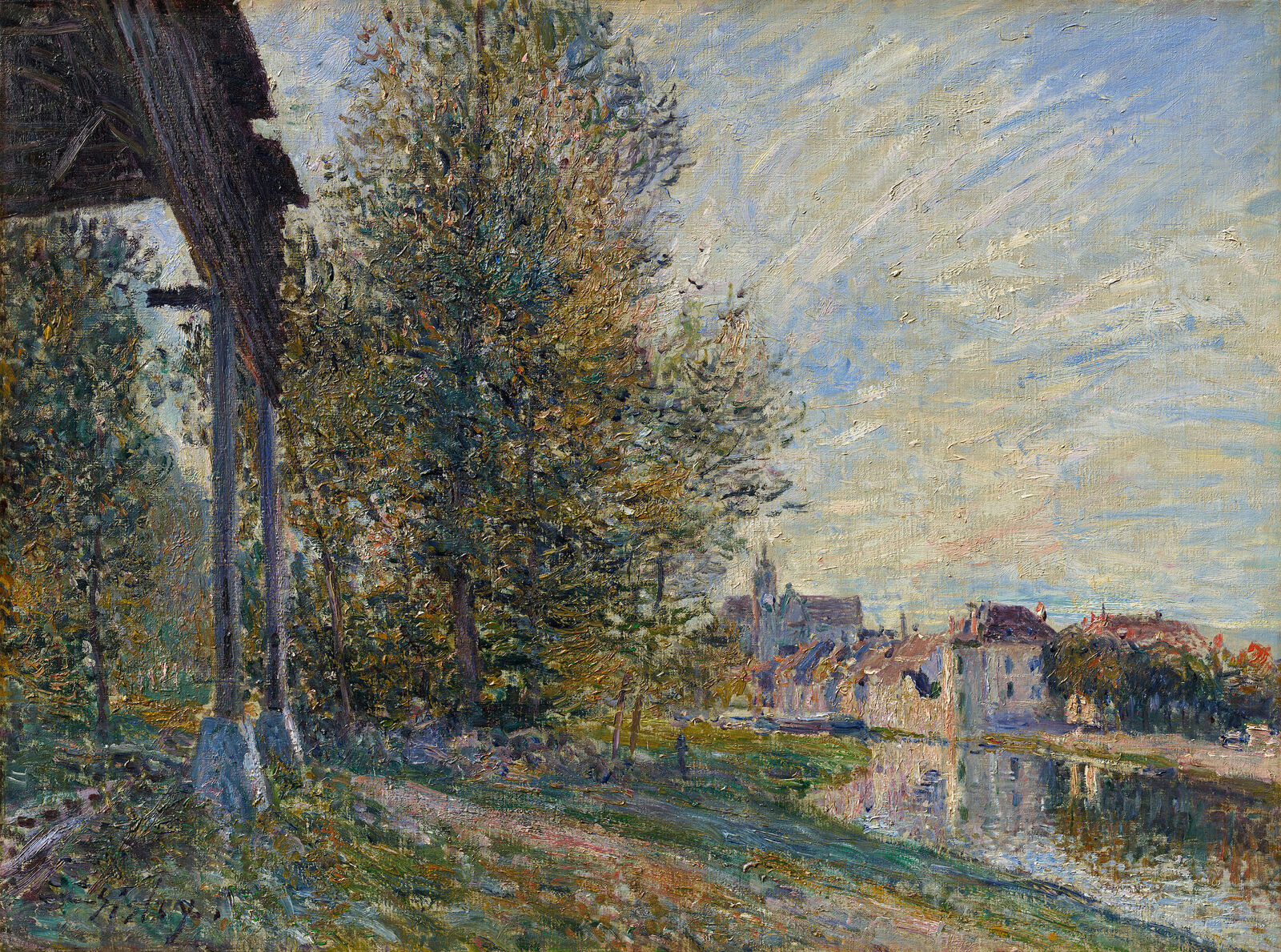

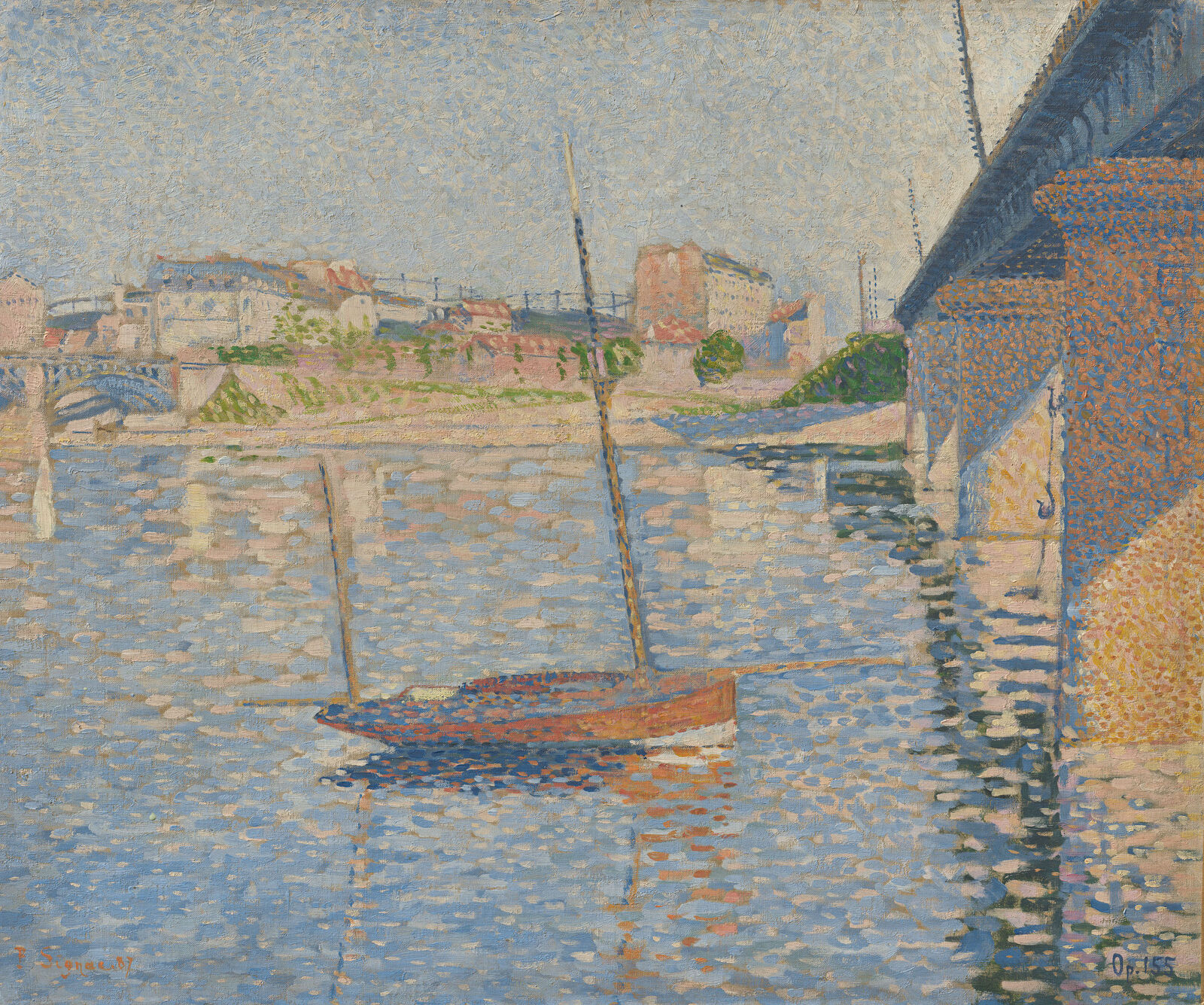

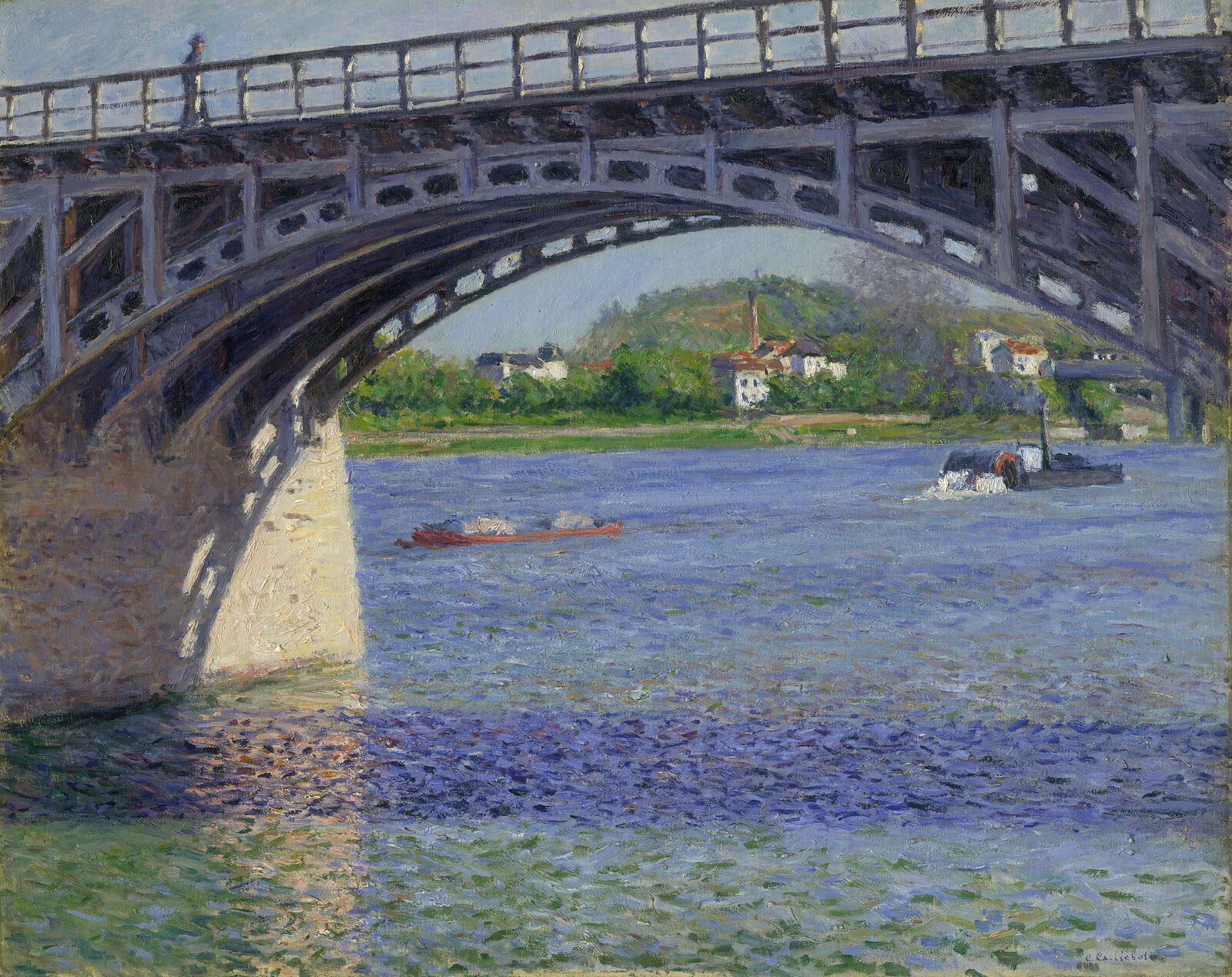

The painters around Claude Monet focused their attention on the ever-changing light and clouds and the reflective surface of the river. In 1865, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley left Paris and embarked upon their first painting excursion along the Seine, going as far as the estuary at Le Havre. To this day, the river towns of Argenteuil, Giverny, and Moret-sur-Loing are associated with Impressionism: there, Eugène Boudin, Gustave Caillebotte, Alfred Sisley, and Paul Signac all explored the Seine with new eyes.

The industrialization of the later 19th century altered the Seine as well.

The river was spanned by ultramodern bridge structures, while steamships transported goods to the rapidly growing capital city of Paris. At the same time, the Seine also became a hub of modern sailing and a popular place of recreation for city-dwellers who traveled by train to the suburbs. Without hesitation, the artists integrated these diverse facets of modern life into their landscape paintings.

Hasso Plattner Collection

Claude Monet: Argenteuil, Late Afternoon, 1872

Gustave Caillebotte: The Argenteuil Bridge and the Seine, ca. 1883

The rapid expansion of the railway network enabled the artists to undertake painting excursions both nearby and further afield, while technical innovations like premixed paint in tubes and portable easels made it practical to paint in the open air for the first time.

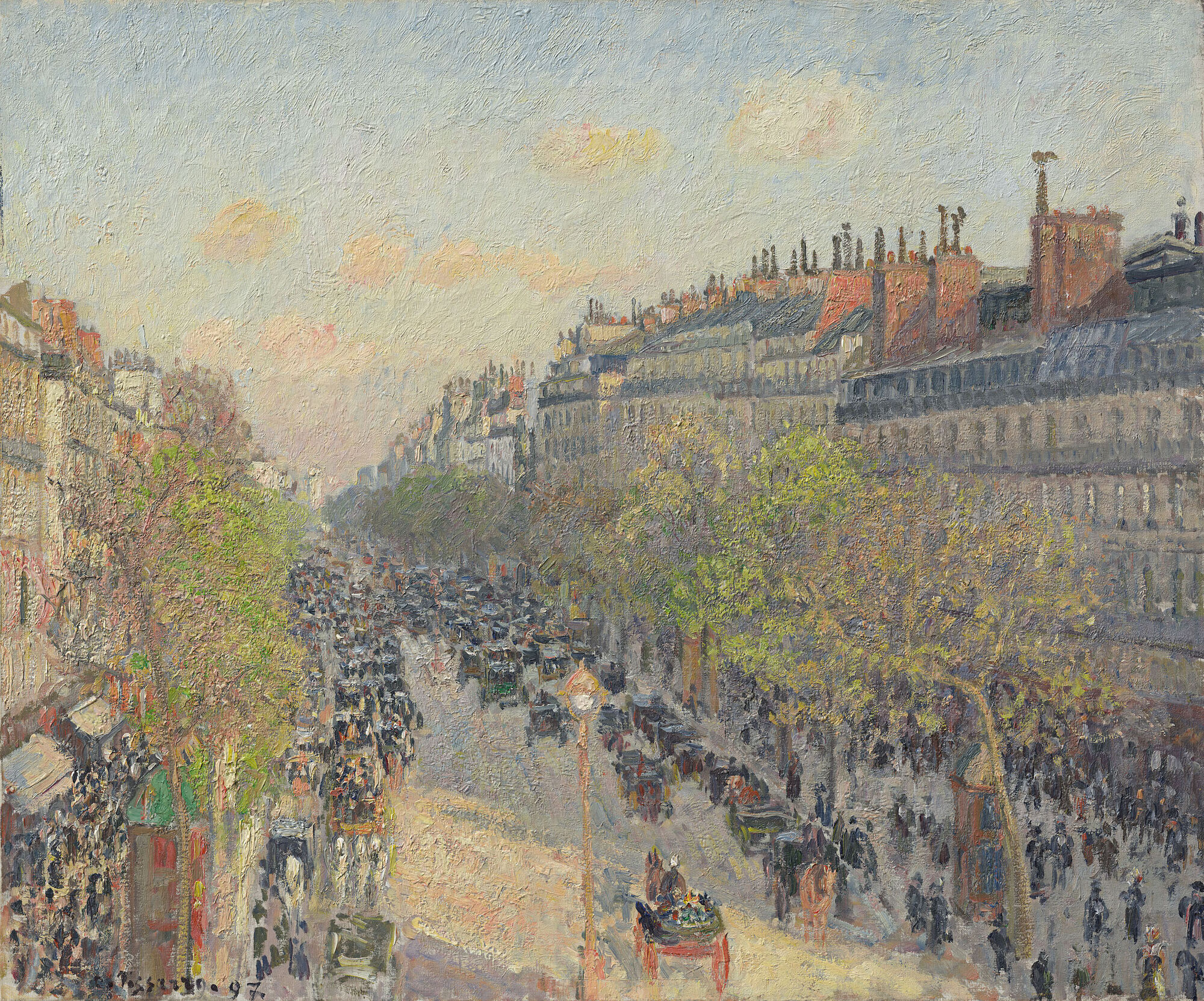

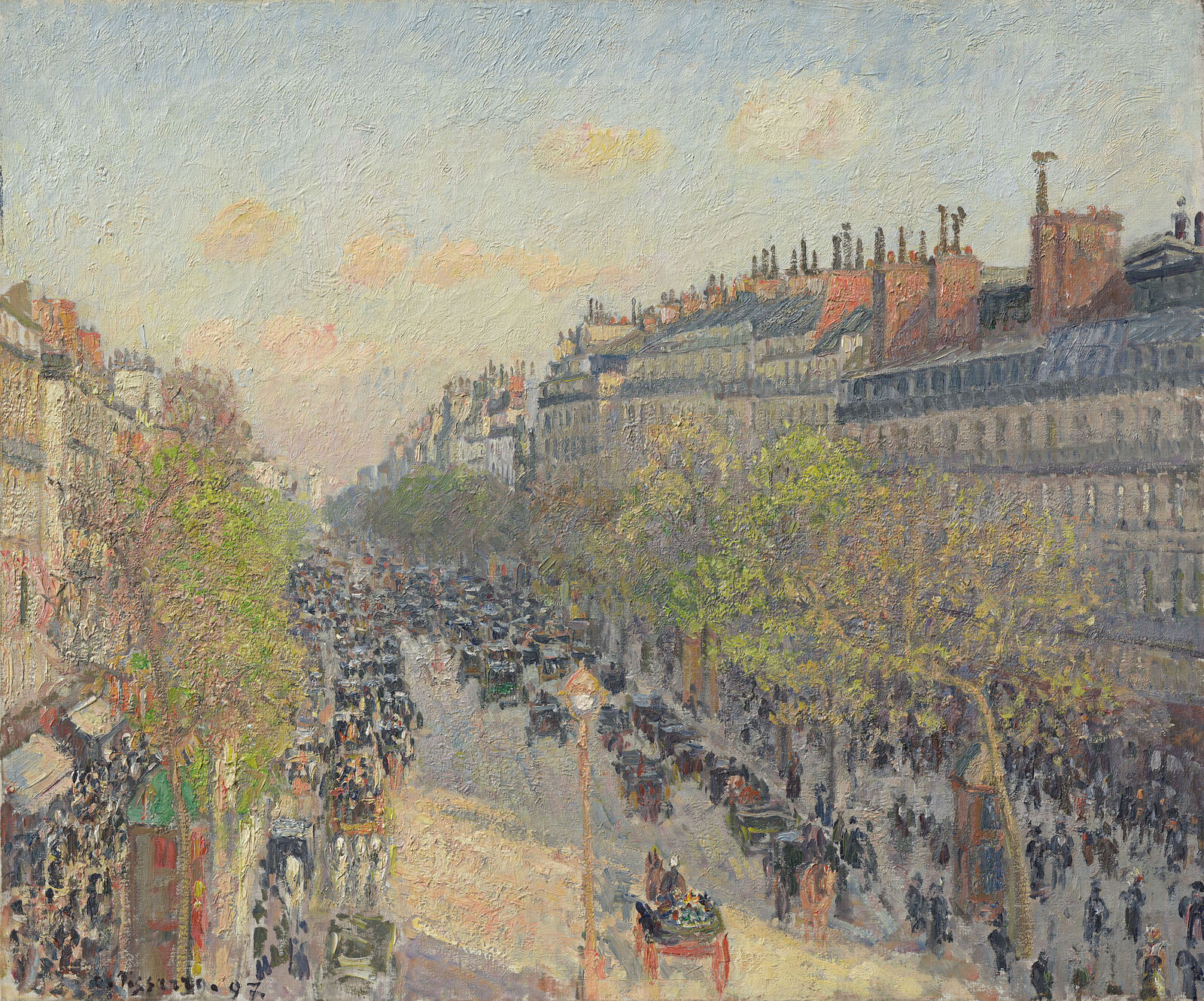

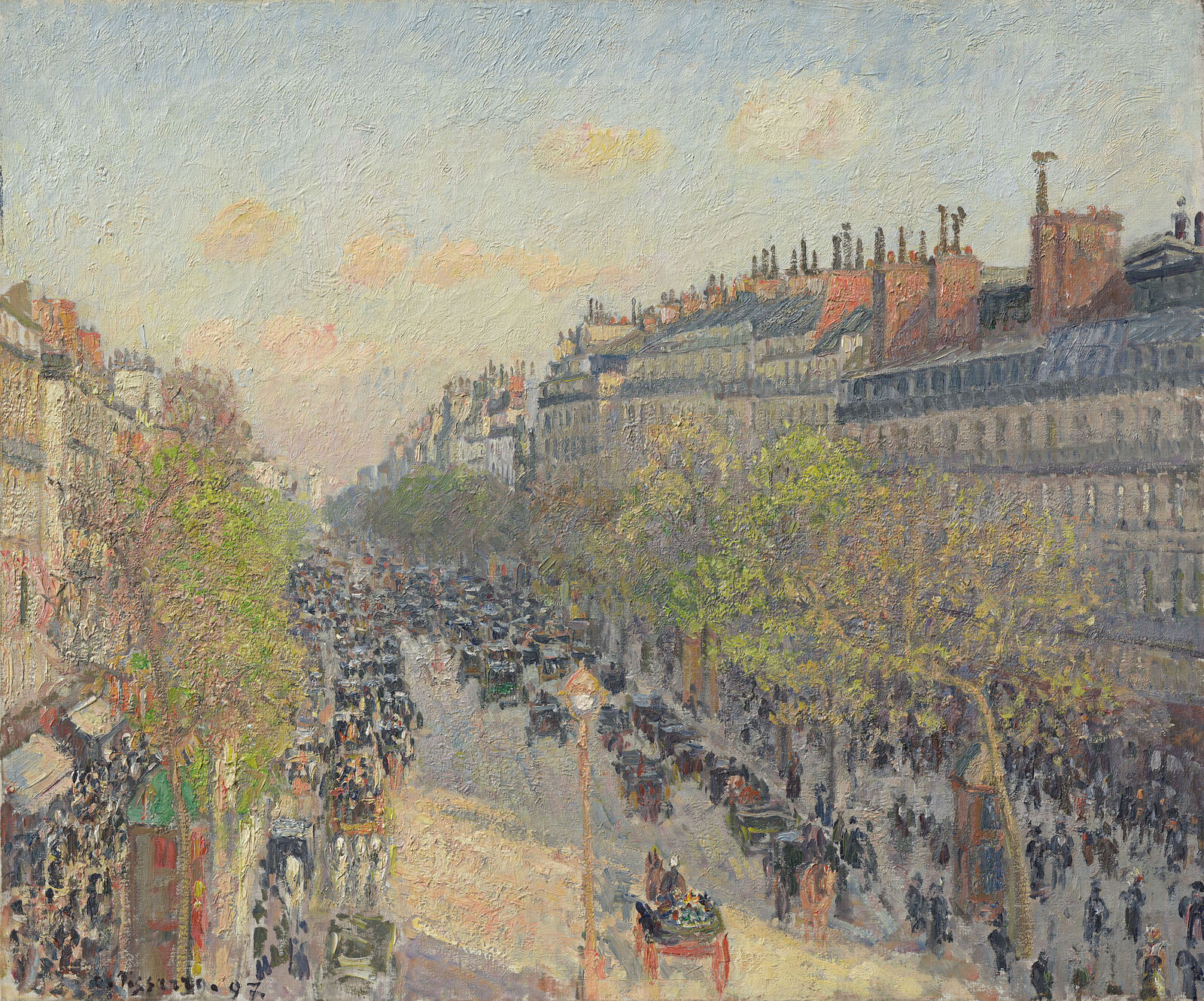

Camille Pissarro: Boulevard Montmartre, Twilight, 1897

The Impressionists observed the life on the boulevards and in the cafés and parks. They experienced the rapid transformation of Paris in the wake of massive reconstruction projects from the 1850s on.

The plans of Baron Haussmann turned Paris into the world’s most progressive metropolis, with wide boulevards and arteries for the swelling flow of traffic, new parks, huge market halls, train stations, and theaters. Here the artists found new, urban motifs—as painters of modern life.

Émile-Othon Friesz: Scene in a Parisian Brasserie, um 1905/06

In 1874, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and their friends organized the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris. Shortly thereafter, Berthe Morisot, Paul Cézanne, and Gustave Caillebotte joined them as well. Artists from around the world came to Paris to become a part of this new modern movement.

Gustave Caillebotte: Rue Halévy, View from a Balcony, 1877

Gustave Caillebotte: Rue Halévy, View from the Sixth Floor, 1878

From 1850 to 1870, the population of Paris doubled to two million inhabitants.

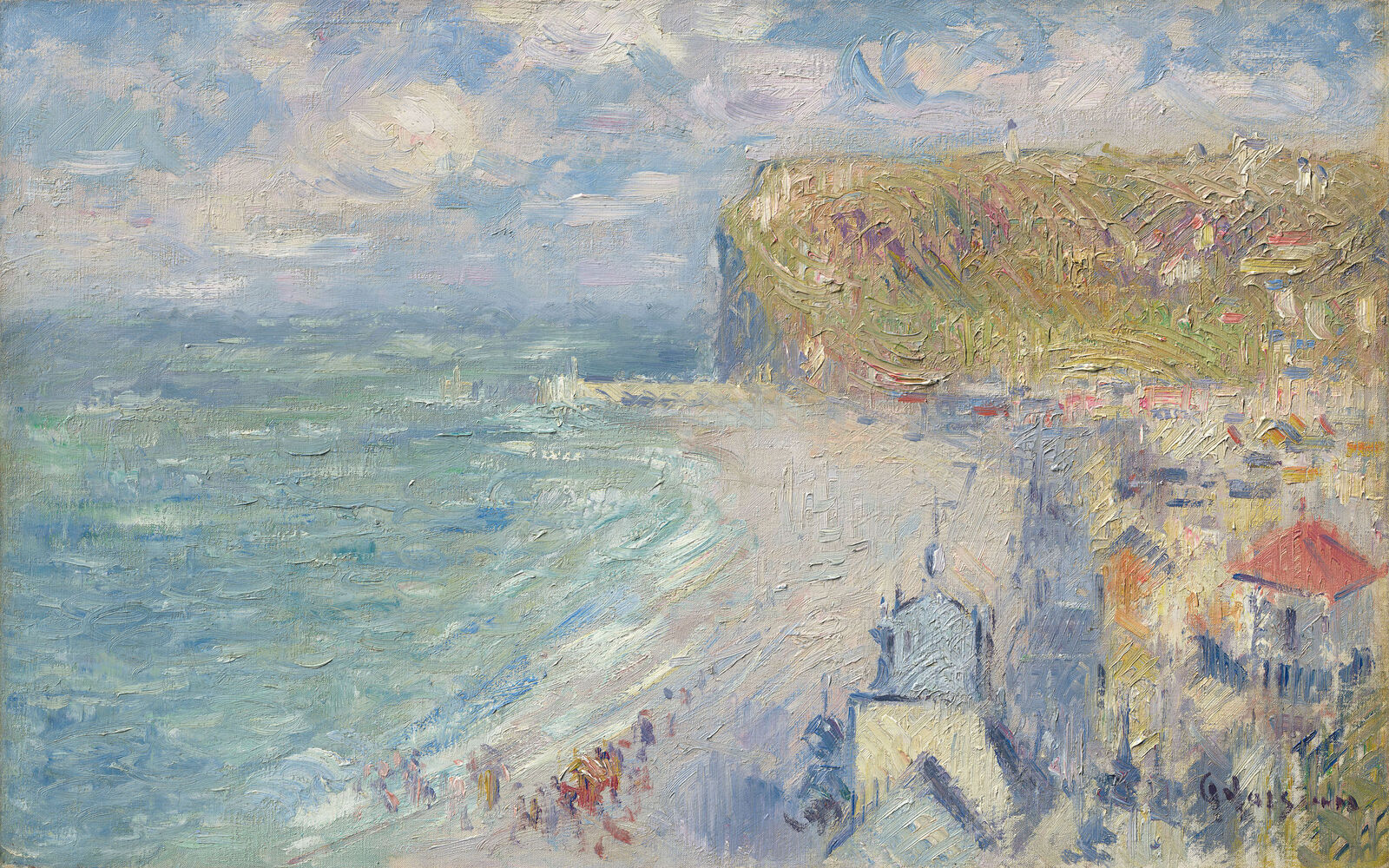

New roads provided access to the periphery, and the suburbs grew as workers and craftsmen fled rising rents in the city center. Parisians in search of recreation could travel just a few hours by train to the coast of Normandy, where fashionable resorts also attracted the Impressionist artists and their collectors.

Gustave Caillebotte: Avenue of the Villa des Fleurs in Trouville, 1883

Gustave Caillebotte: Couple on a Walk, 1881

Along with the “Haussmannization” of Paris, the Impressionists were especially fascinated by the modern recreational idyll of Normandy.

Gustave Caillebotte, for example, liked to spend the summer in Trouville on the Normandy coast. With its luxury hotels, casinos, and villas, the town was a popular destination for affluent Parisian guests.

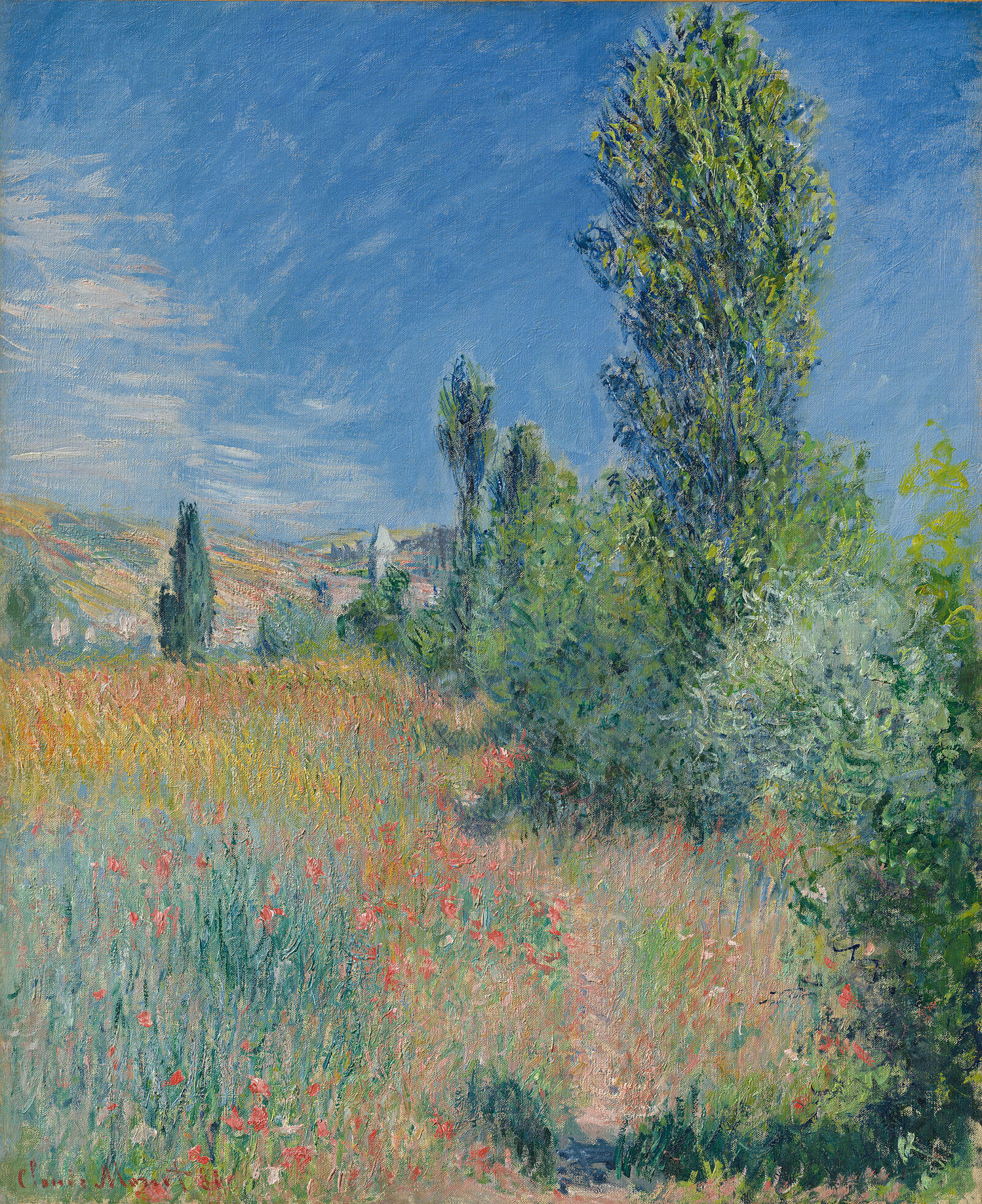

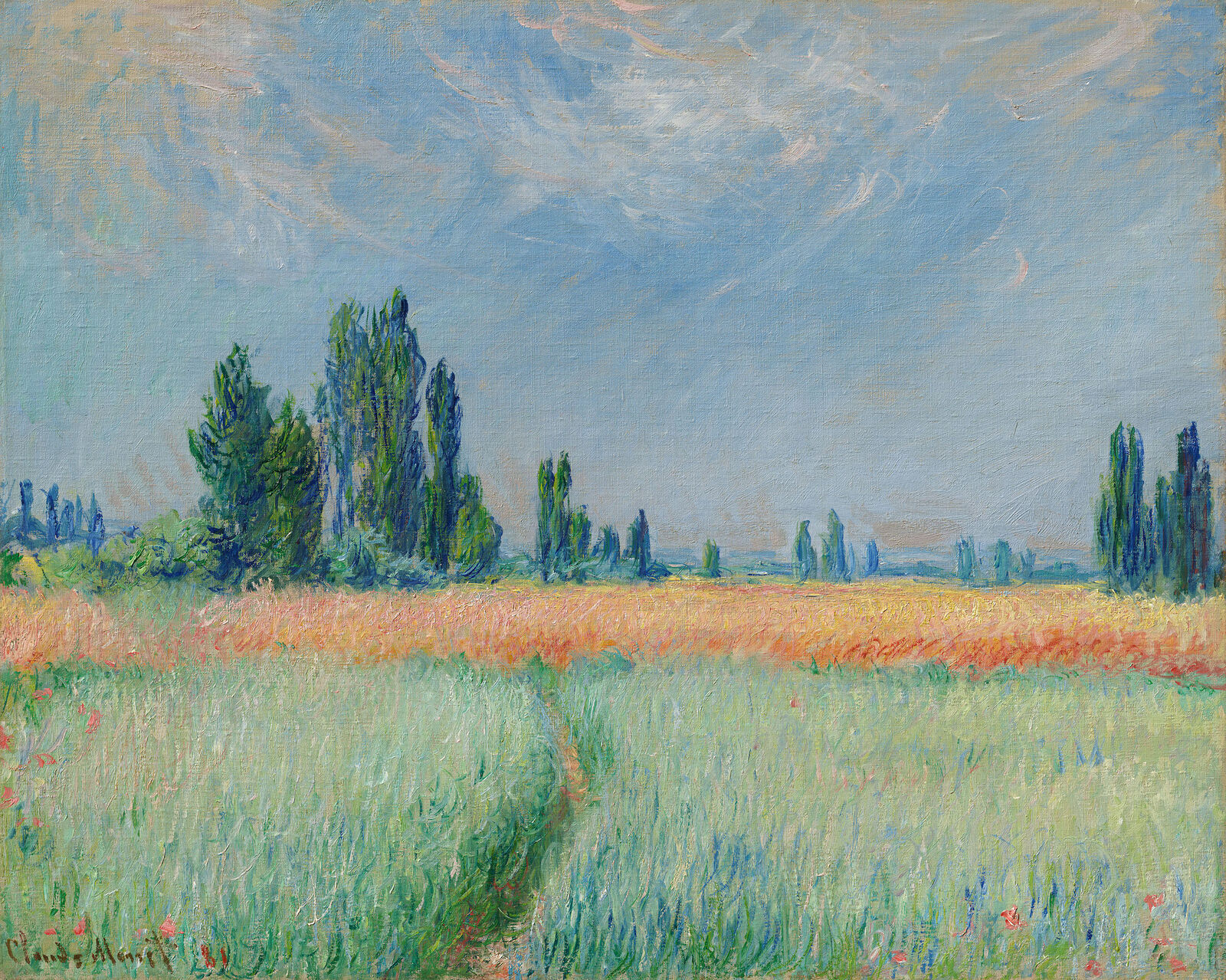

Claude Monet: Poplars at Giverny, 1887

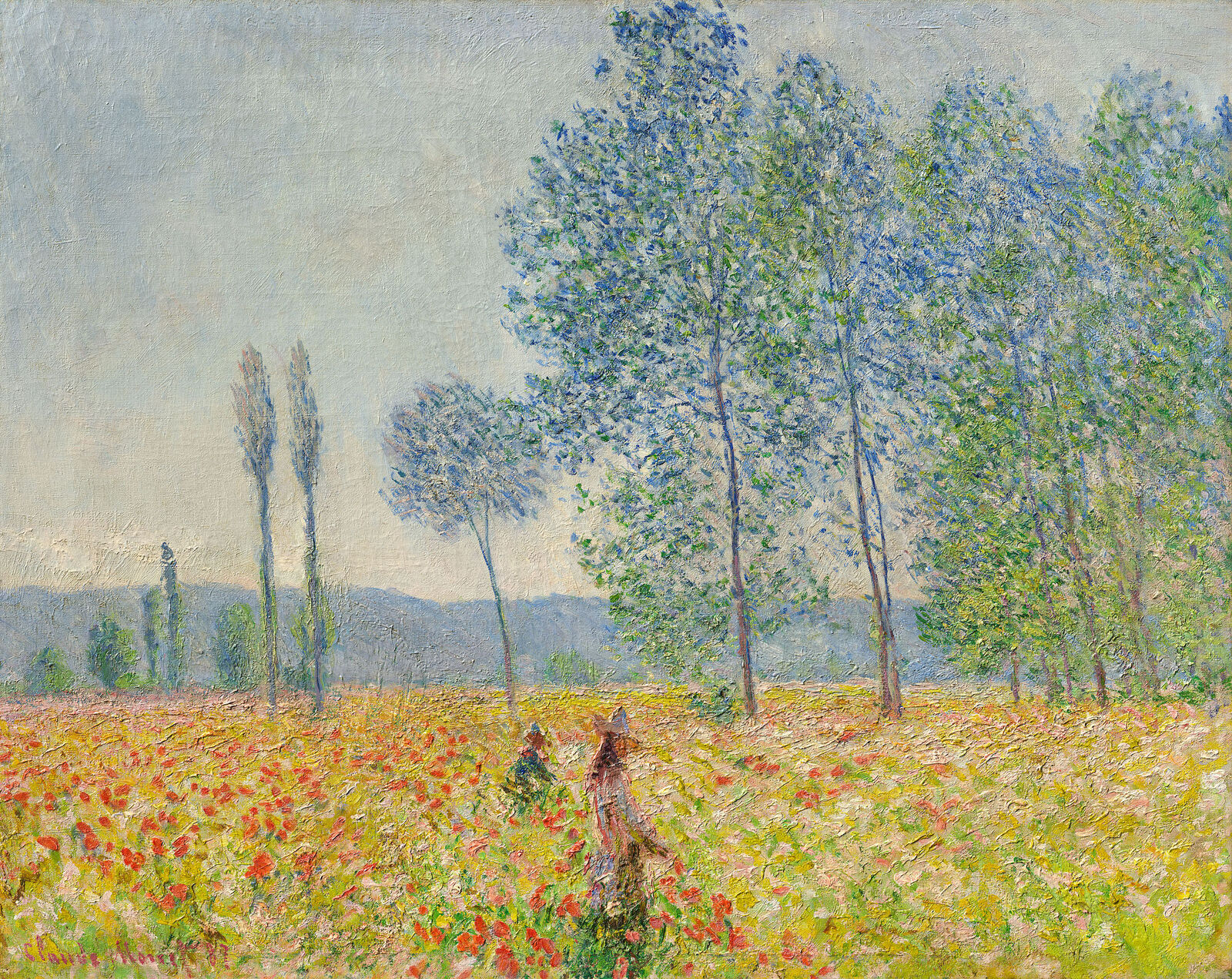

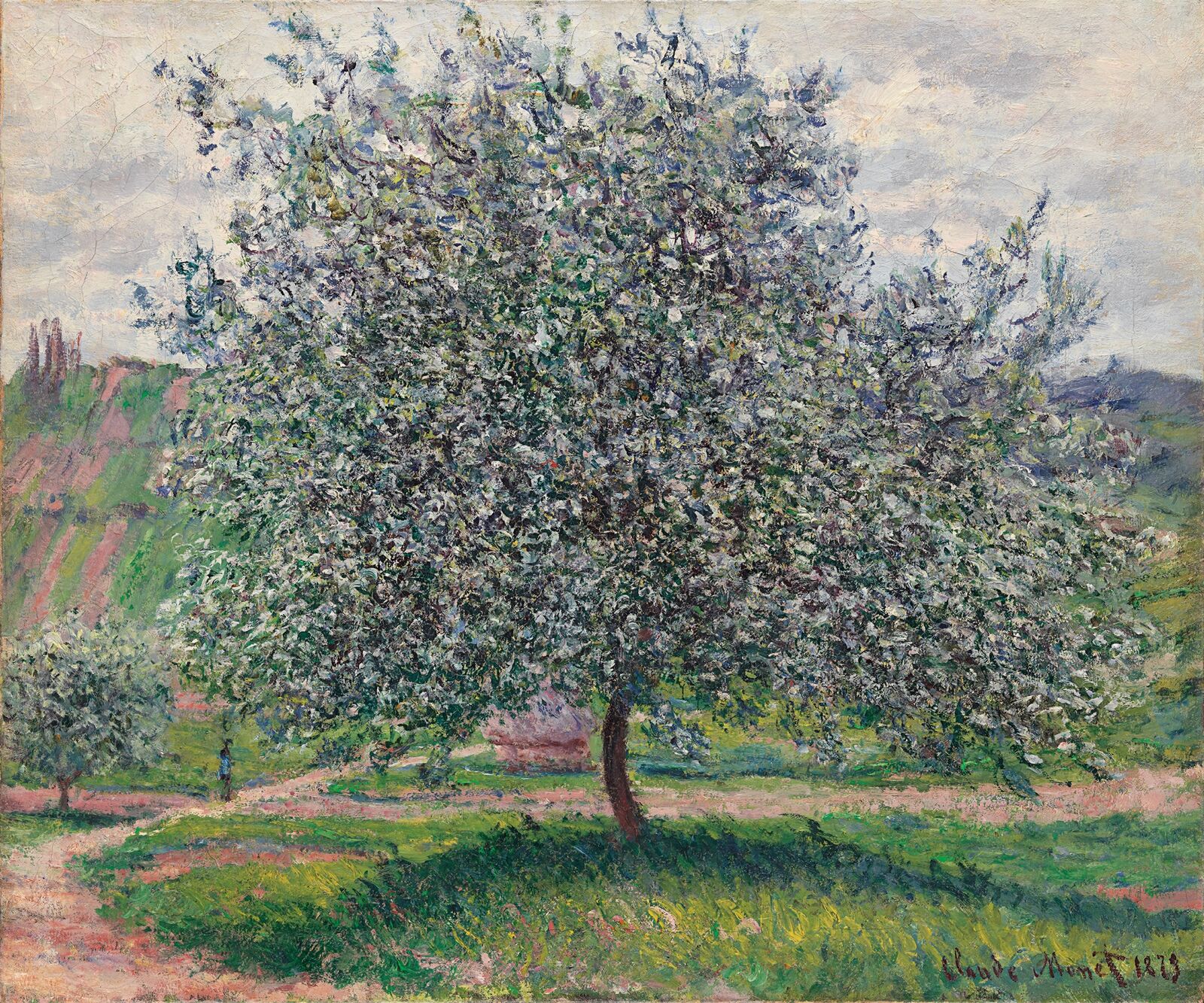

The Impressionists chose unassuming motifs, capturing the fields of grain, rows of poplar trees, country lanes, meadows, and grainstacks near the towns where they lived. These French landscapes, devoid of nostalgic clichés, appealed to audiences in Paris. The innovative views of nature are animated by lively brushwork.

With their freshness and authenticity, these images of nature were groundbreaking for their time and still invite modern-day viewers to experience the light, air, times of day, and seasons with all their senses. Despite the looseness of the brushwork, the artists accurately captured the topography of the landscape.

Following in the footsteps of the Barbizon artists, from 1862 on Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir embarked on painting excursions to the forest of Fontainebleau near Paris.

Working directly from nature, they explored the dissolution of form and developed a new, expansive airiness, capturing atmospheric phenomena that were also being studied by 19th-century scientists. The resulting paintings are not arbitrary evocations of a mood, but a record of direct experience, with data in every brushstroke.

Hasso Plattner Collection

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Path in the Forest, 1874–1877

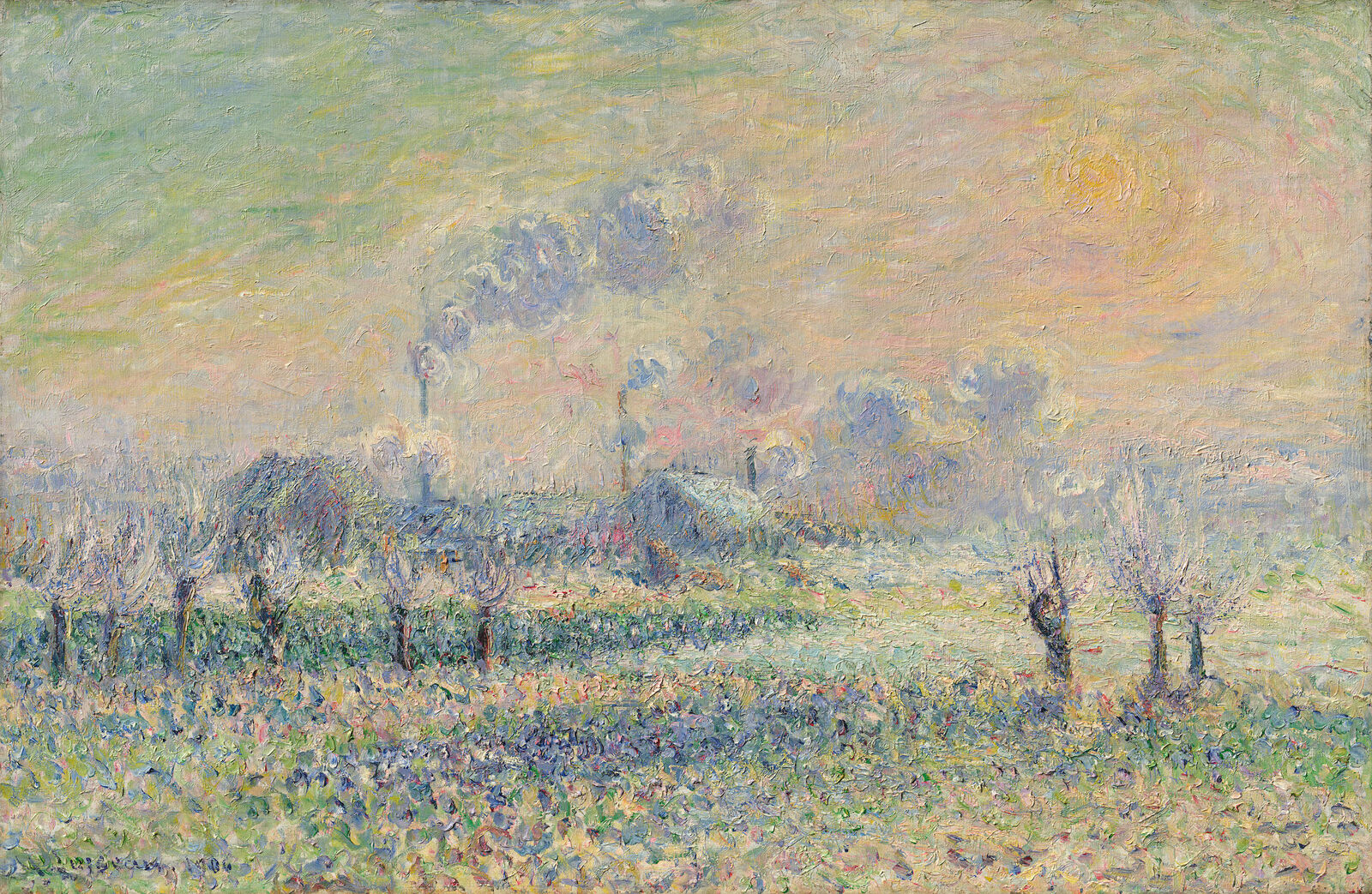

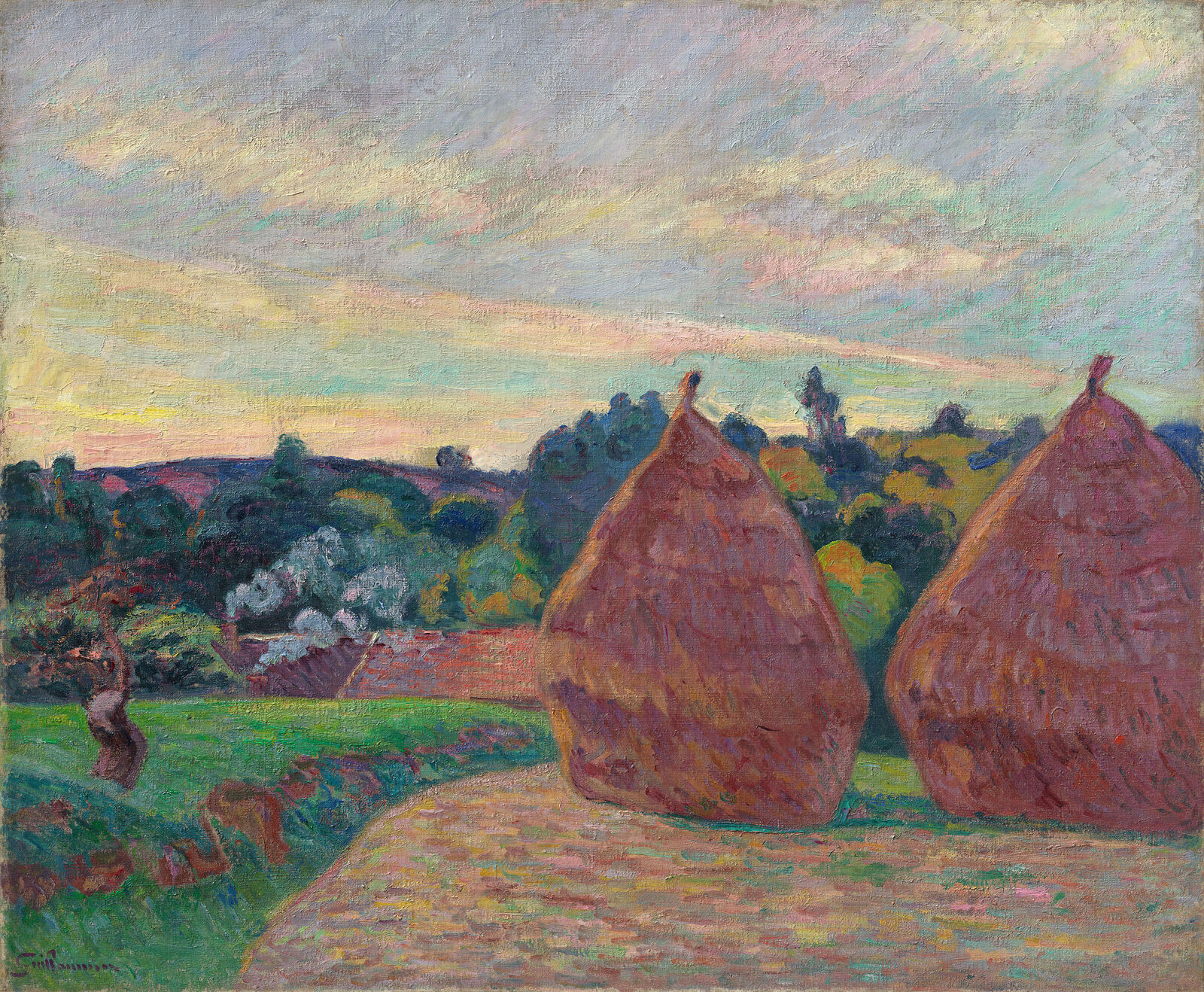

City-dwellers viewed the countryside of France with different eyes than the farmers. While Camille Pissarro focused his attention on the rural inhabitants themselves, Armand Guillaumin, like Monet, showed the striking grainstacks as visible evidence of agricultural labor.

Hasso Plattner Collection

Armand Guillaumin: Grainstacks at Île-de-France, ca. 1894

Hasso Plattner Collection

Camille Pissarro: Hoar-Frost, Peasant Girl Making a Fire, 1888

For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life—the air and the light, which vary continuously.

Eugène Boudin: Le Havre: Sunset on the Sea, 1885

Hasso Plattner Collection

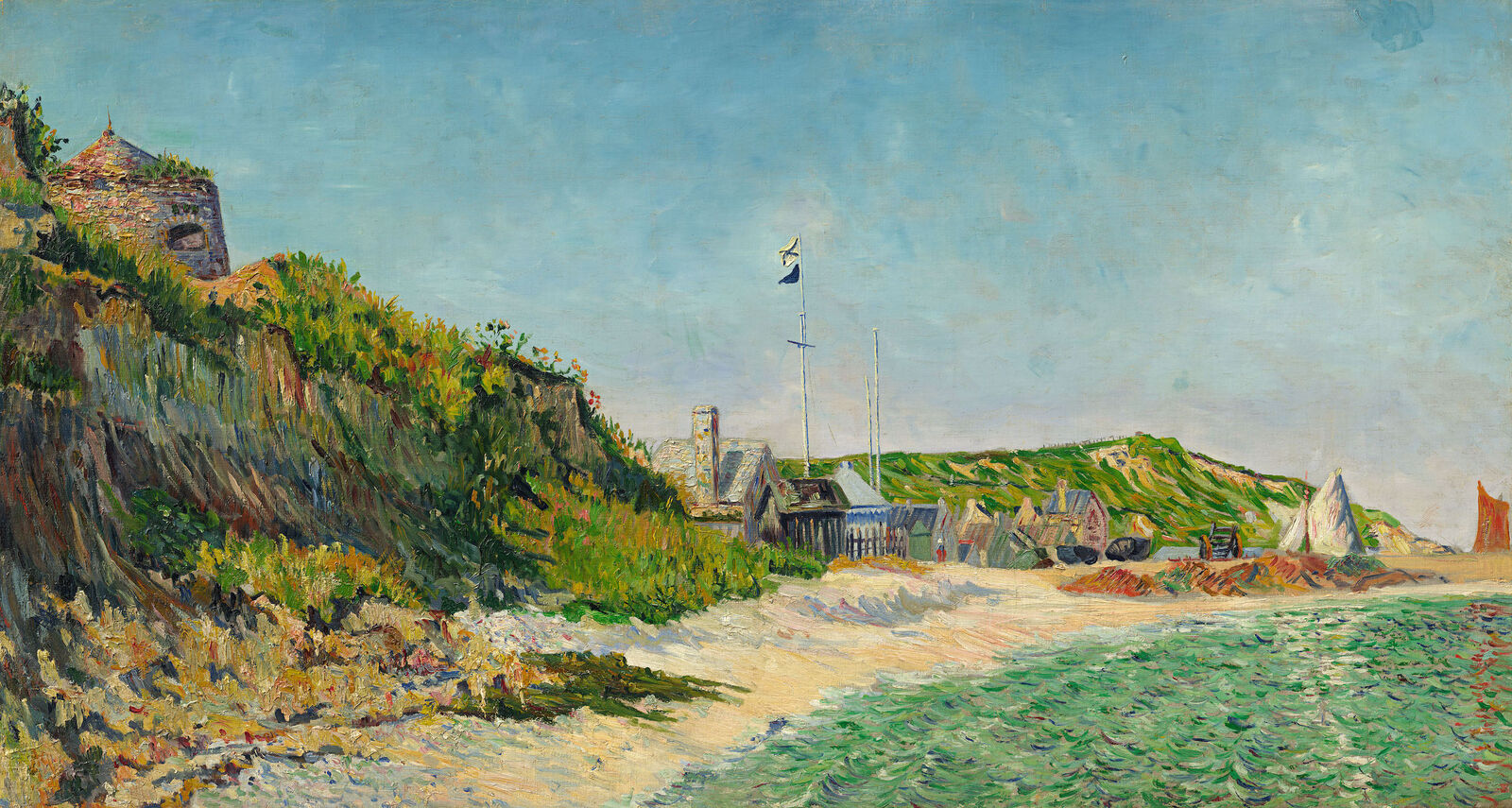

The coasts of Brittany and Normandy grew in economic importance over the course of the 19th century, and their harbors were progressively modernized. Le Havre was the second largest port in France, with overseas trade to America. Here Claude Monet produced his first paintings.

Eugène Boudin was a pioneer of plein air painting, which he introduced to the young Claude Monet. With its rapid alternation of sun and clouds, the coast was a place where plein air painters could hone their ability to capture the fleeting moment.

Everything that is painted directly and on the spot has always a strength, a power, a vivacity of touch which one cannot recover in the studio.

Eugène Boudin: Honfleur: The Port, ca.1858–1862

The artists drew inspiration from the painting of the Old Masters, while also embracing the modernity of the port cities. They observed how artificial lighting and the new pace of commerce altered the traditional harbor towns.

Claude Monet had seen the largest port in the world in London. In 1872, shortly after his return to France, he painted Impression, Sunrise in Le Havre (Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris), a sketch-like work that is now considered seminal and caused a sensation at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. As a pendant, Monet also painted a night scene using rapid, fleeting brushstrokes to evoke the industrial port with its artificial gas lighting.

Berthe Morisot was the only woman who belonged to the circle of the Impressionists from the beginning. Like Claude Monet, she visited London, where she encountered not only the British docks, but also the atmospheric views of the Thames by William Turner.

Hasso Plattner Collection

Claude Monet: The Port of Le Havre, Night Effect, 1872

Berthe Morisot: The Thames, 1875

The Thames is truly beautiful … the whole thing bathed in a golden haze.

Camille Pissarro: Garden and Henhouse at Octave Mirbeau's, Les Damps, 1892

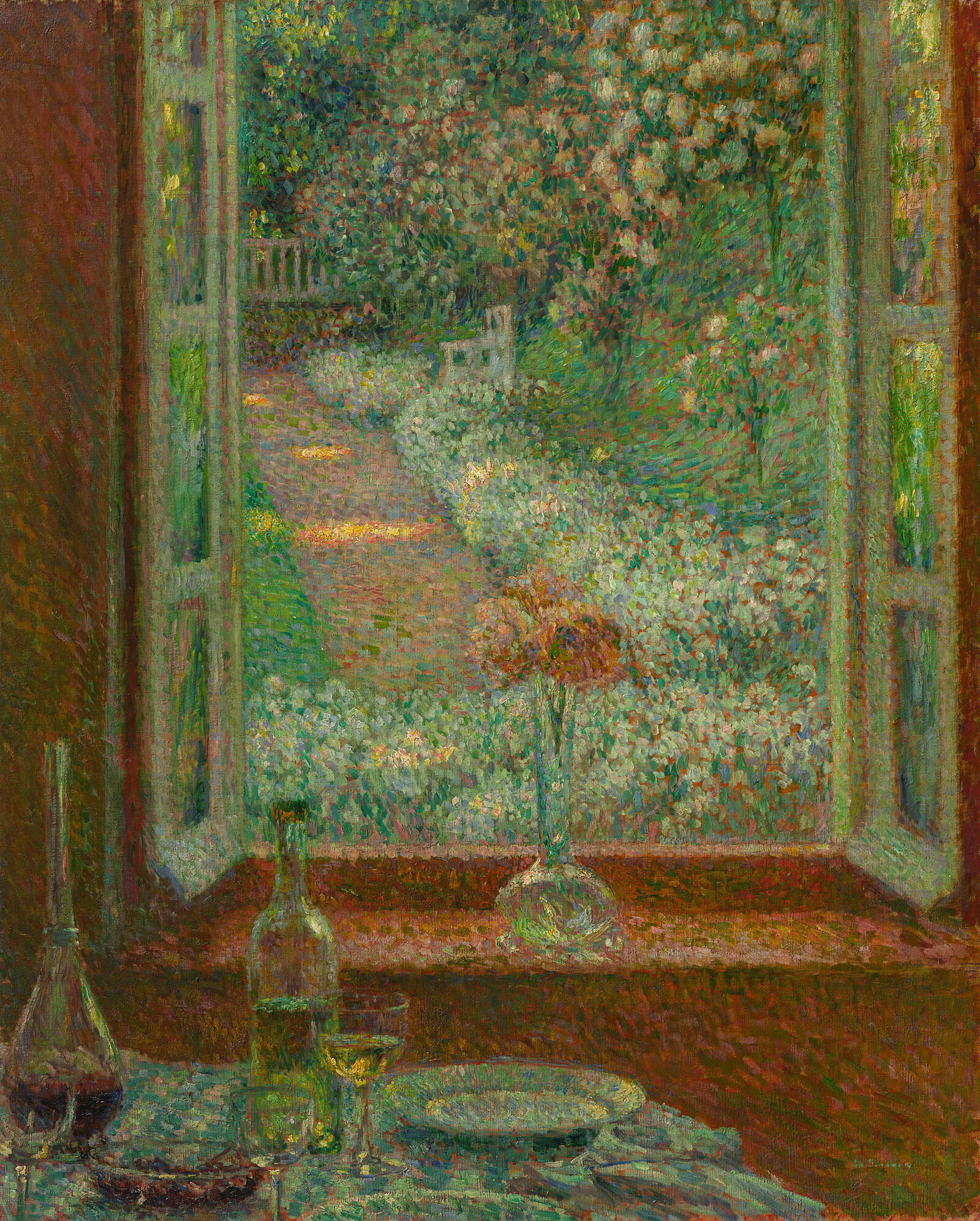

In the 19th century, gardening became a popular hobby among the educated classes. The interest in exotic plants increased as well. The artists around Claude Monet enthusiastically cultivated their love of variability in their own gardens.

The Impressionists embraced this new theme as a way to explore the changing of the seasons and the times of day. In addition, the artists’ own gardens could serve as open-air studios, in close proximity to their subject matter. In the interplay of interior and exterior spaces, the garden scenes embody a harmonious vision of human life in nature.

Like Monet in Giverny and Caillebotte in Le Petit-Gennevilliers—both passionate gardeners—the painter Henri Le Sidaner found a paradisiacal retreat in the medieval village of Gerberoy. Around his estate he planted a flower garden in the English style, which would become the most important backdrop for his painting.

Fragrant flowers and ripe fruits, often cultivated in their own gardens, inspired the artists to create Impressionist still lifes. With their free, experimental approach to painting, they developed entirely new facets of this traditional Old Master motif.

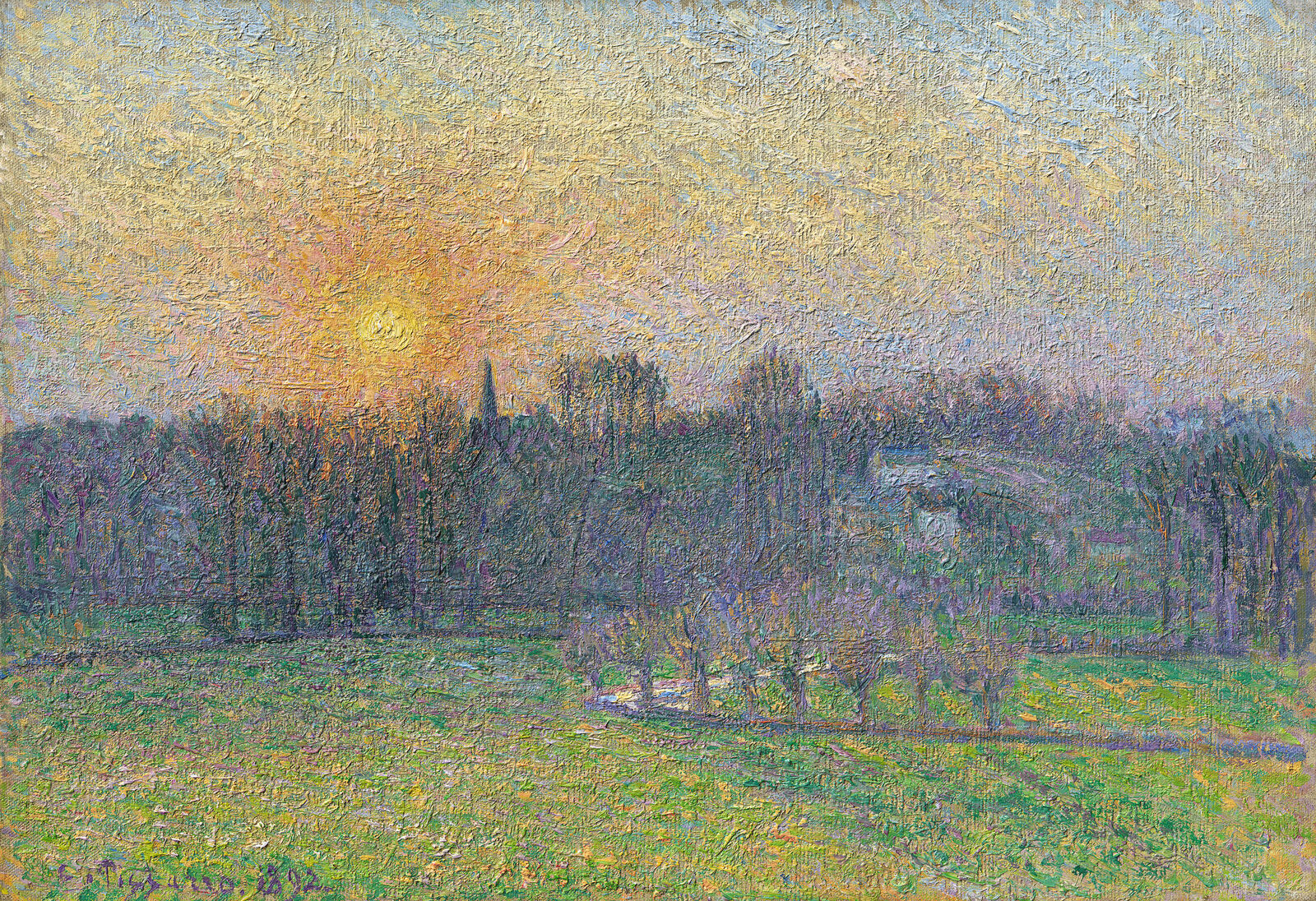

Camille Pissarro: View of Bazincourt, Snow Effect, Sunset, 1892

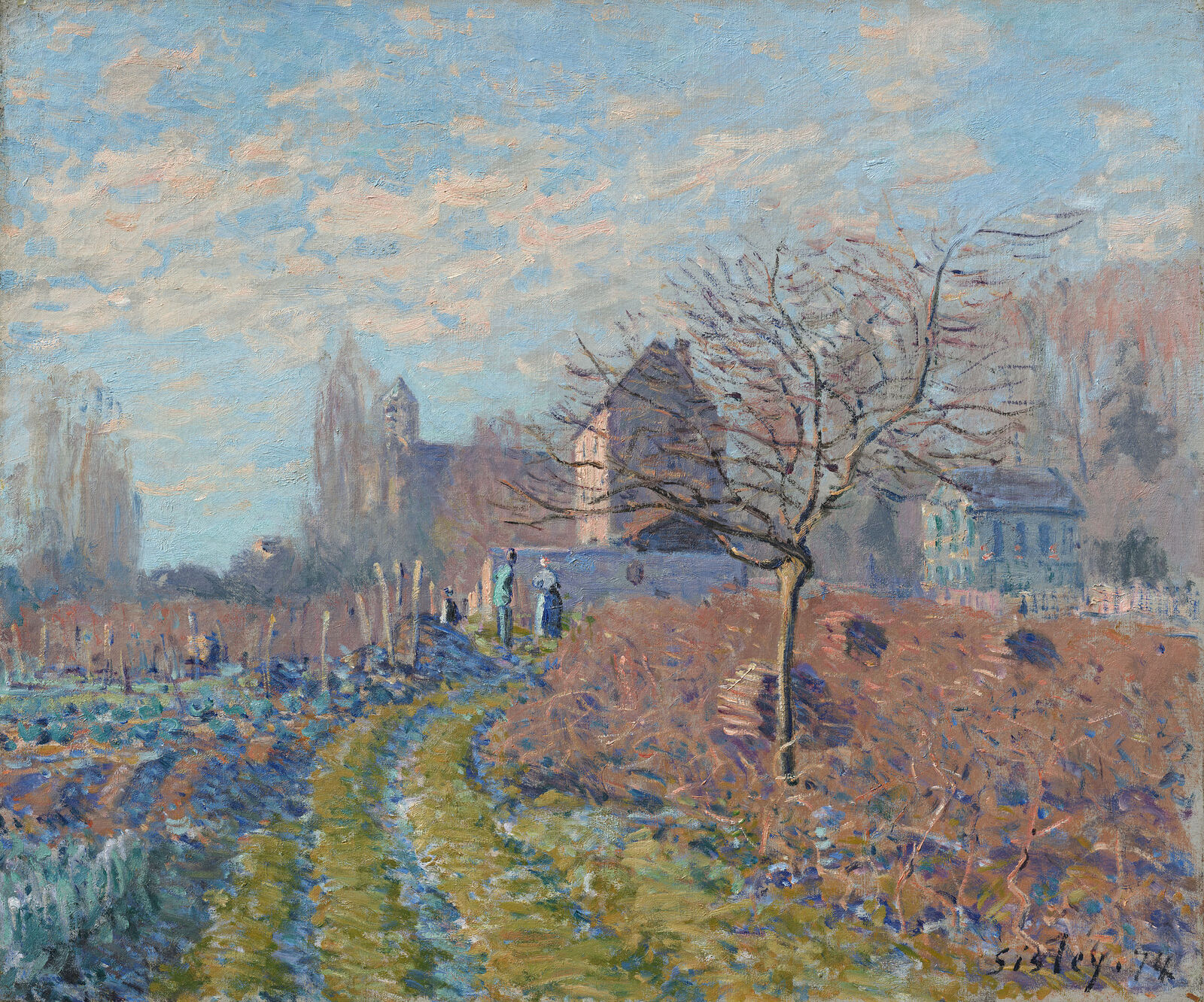

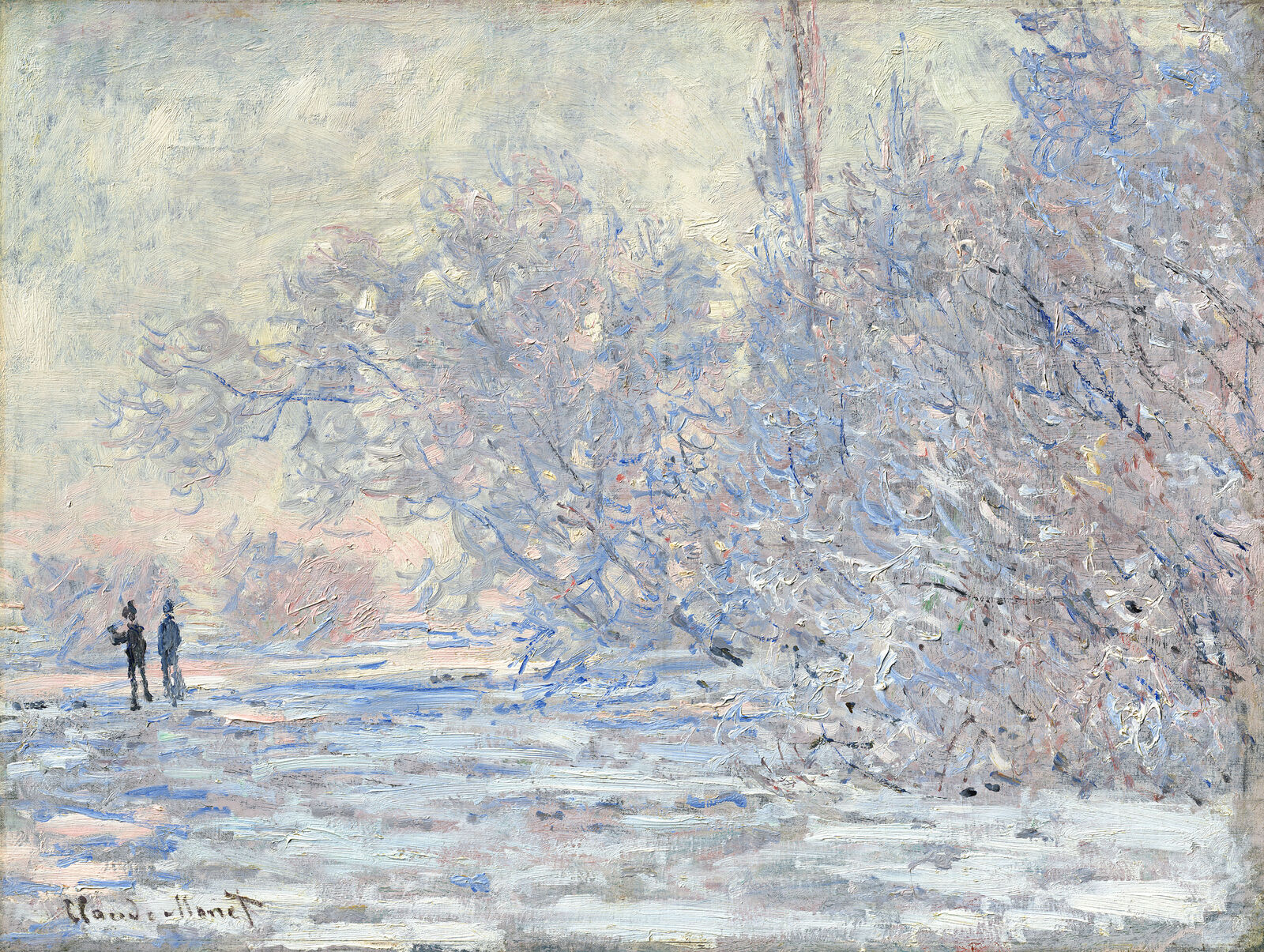

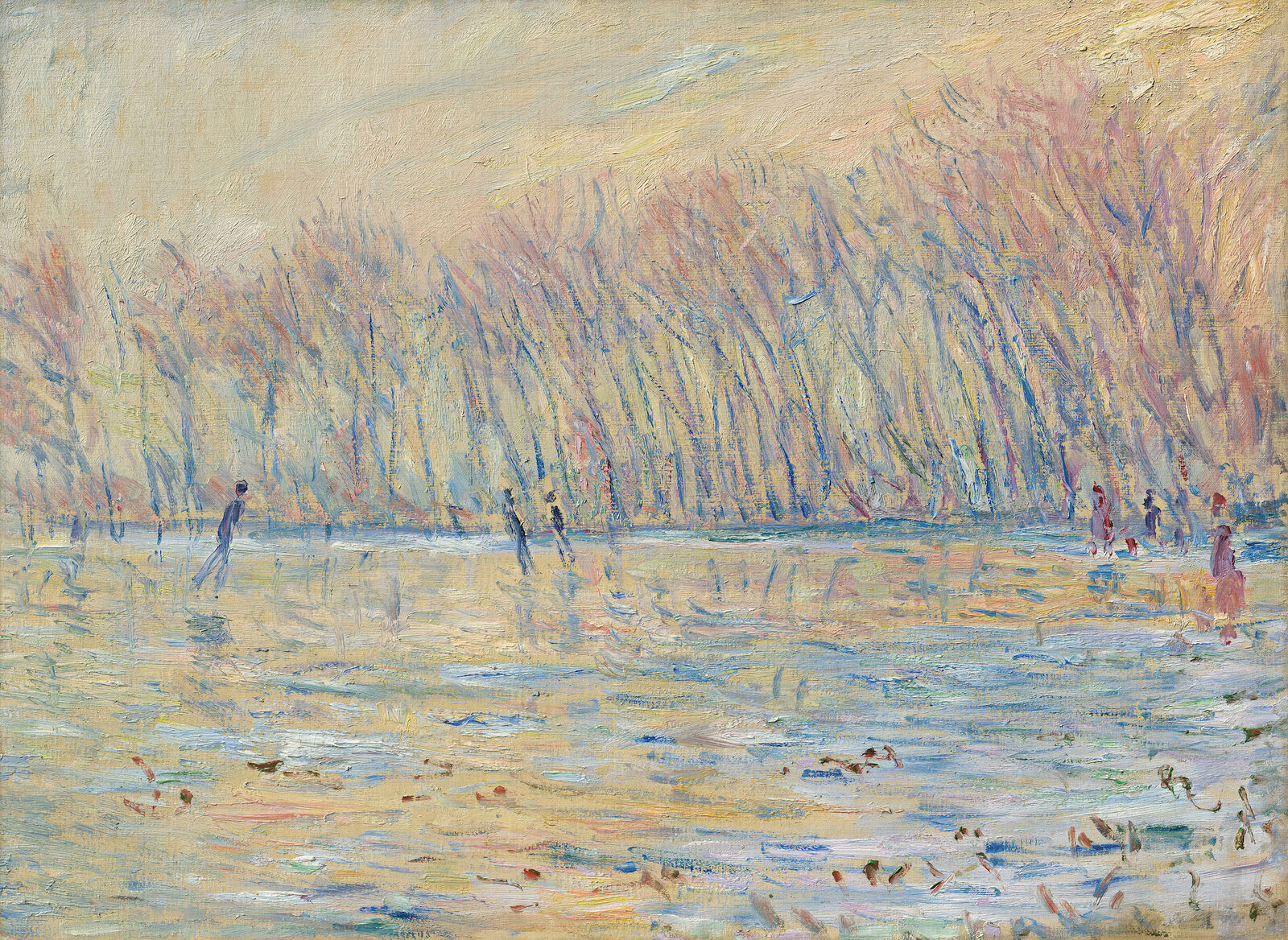

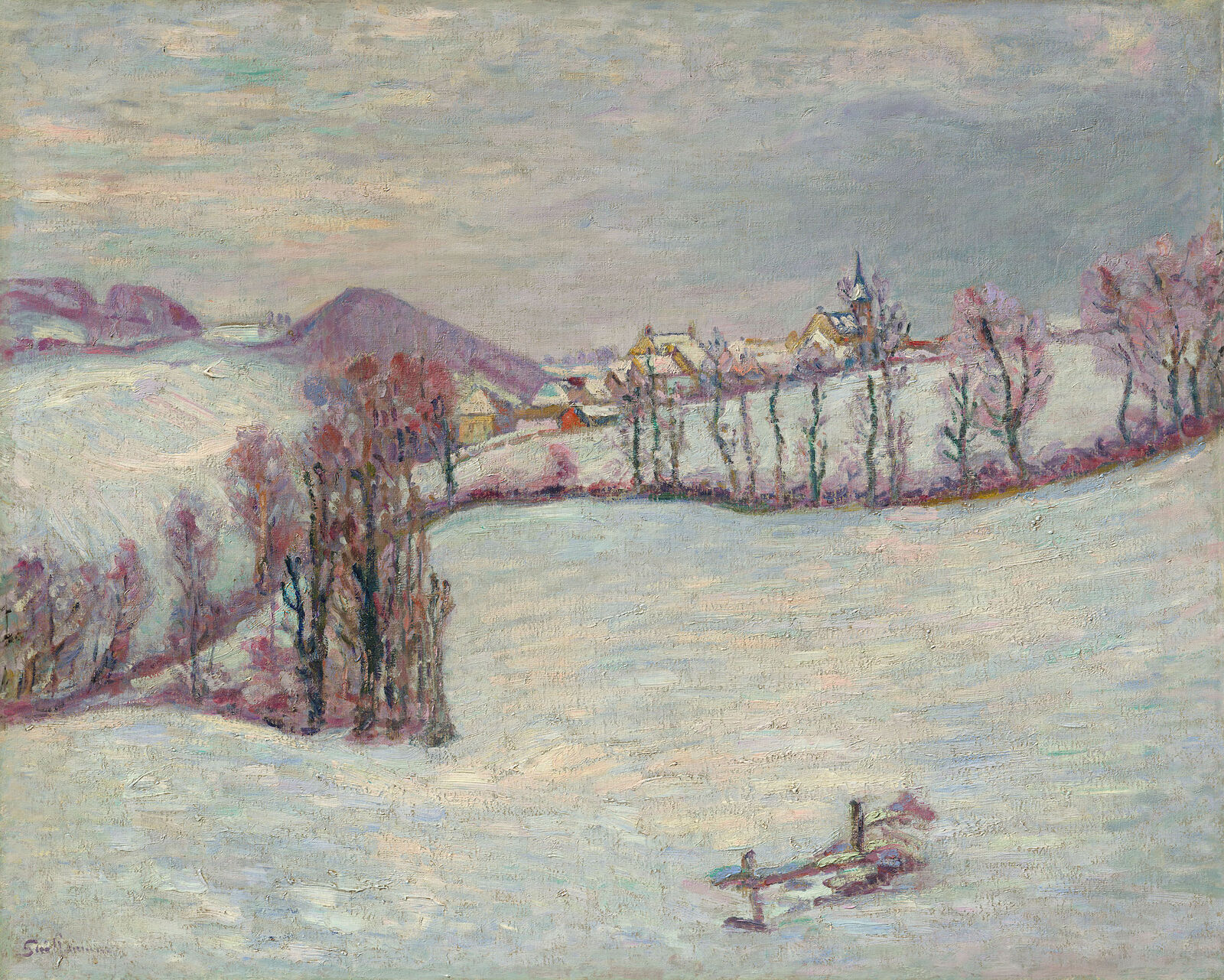

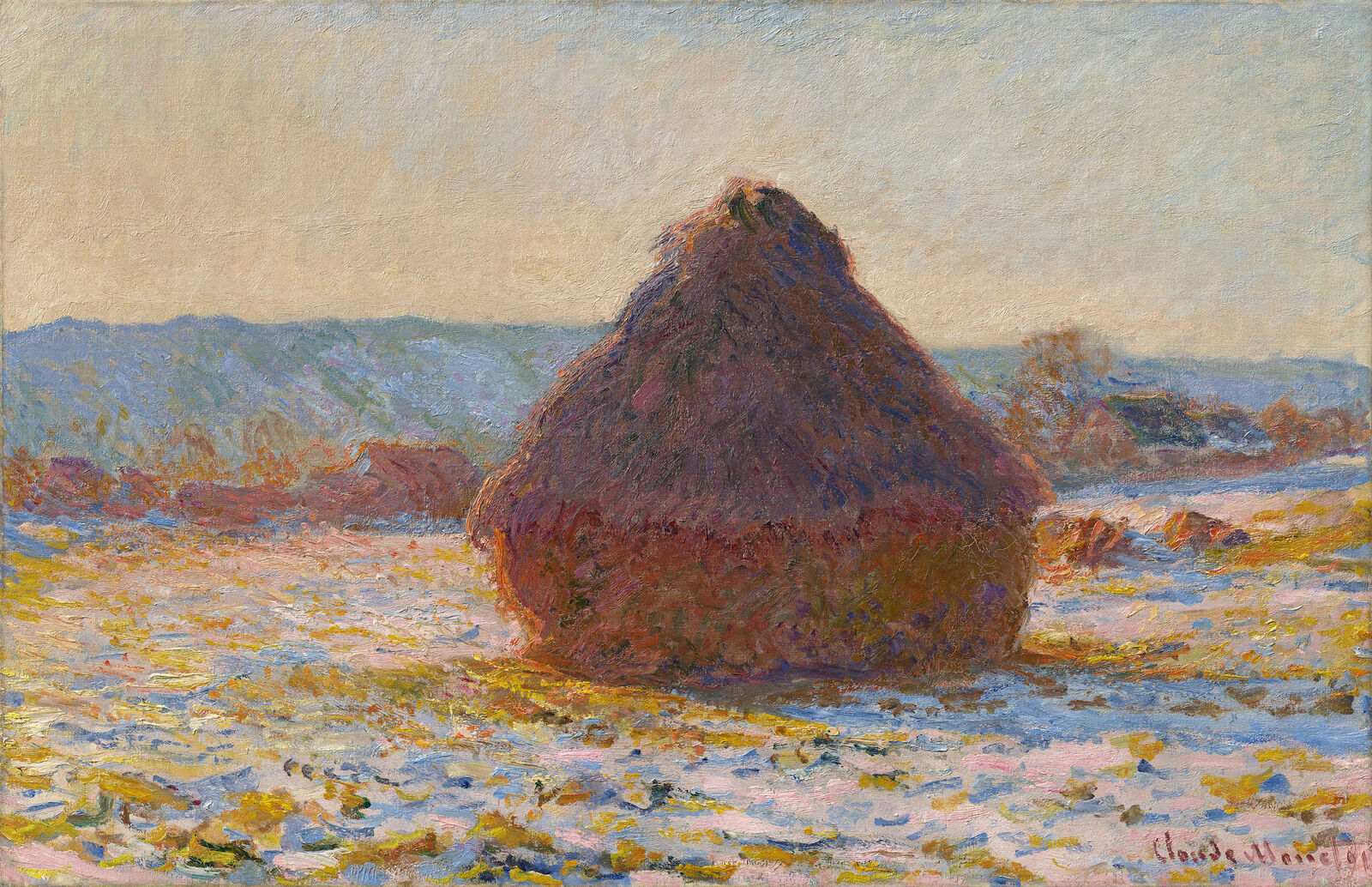

The winters from the 1860s to the 1890s were accompanied by especially heavy snowfall. Undaunted by the icy cold and the difficulty of painting outdoors, the artists pursued their interest in the optical phenomena of light refracting on crystals of snow.

The white blanket of snow gives the everyday landscape a sense of unfamiliarity. The painters evoked the reflections on the snow in compositions that seem almost abstract, joining sky and earth in atmospherically dense images.

Of all the Impressionists, Monet painted the largest number of winter scenes, around 140 in all. His interest in the subject was inspired by images in colored Japanese woodcuts, which he enthusiastically collected.

Claude Monet: Floes at Bennecourt, 1893

Renoir insisted that snow should never be painted pure white, since the blanket of snow reflected all the colors of the environment. The winter paintings of Alfred Sisley are marked by vividly colored shadows. His preferred subject matter was the sky and water throughout the changing seasons.

Alfred Sisley: Snow Effect in Louveciennes, 1874

Objects should be painted … bathed in light … The sky … reminds us of the movement of waves on the ocean, inspires us, and carries us away … I always start a painting with the sky.

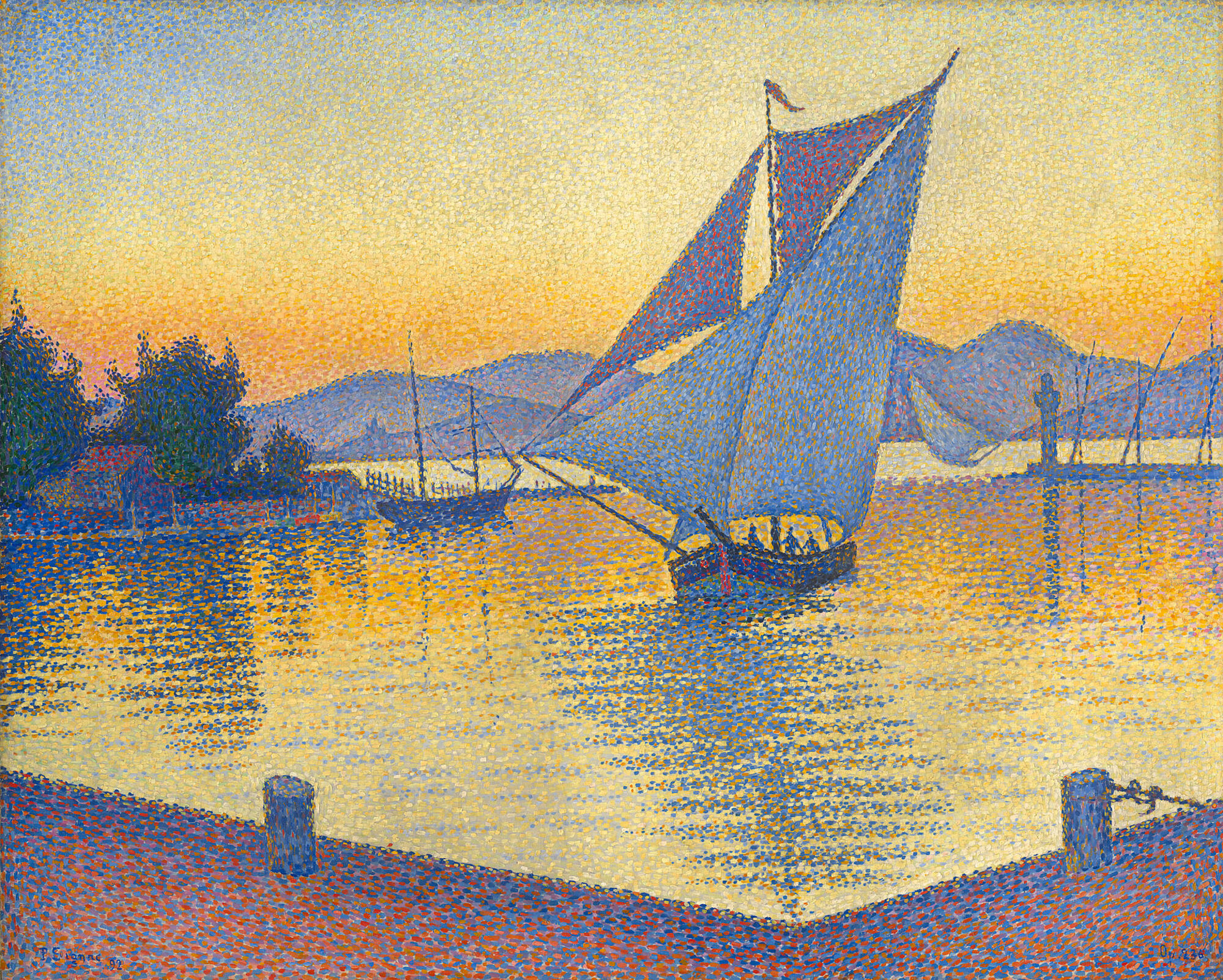

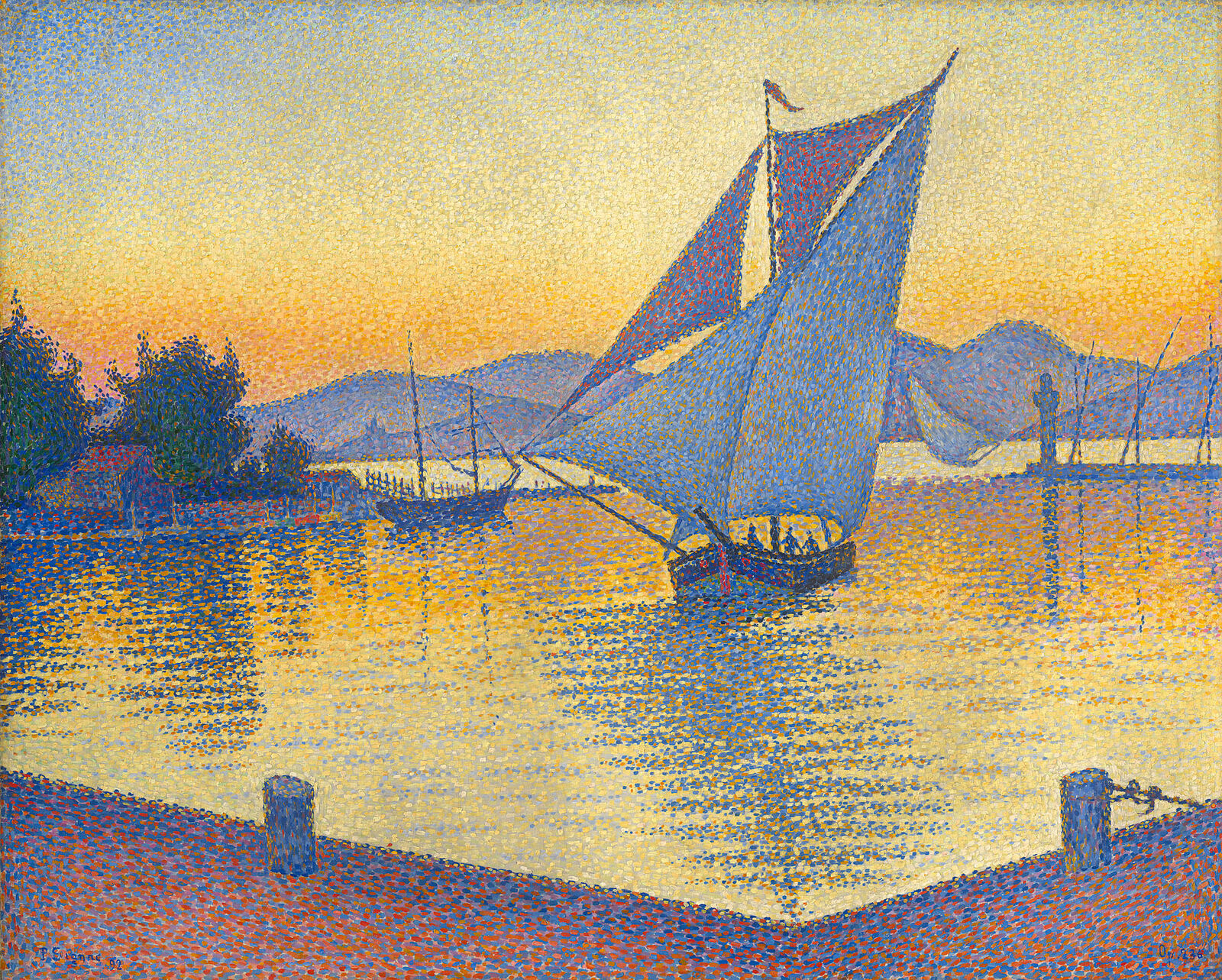

Paul Signac: The Port at Sunset, Opus 236 (Saint-Tropez), 1892

Hasso Plattner Collection

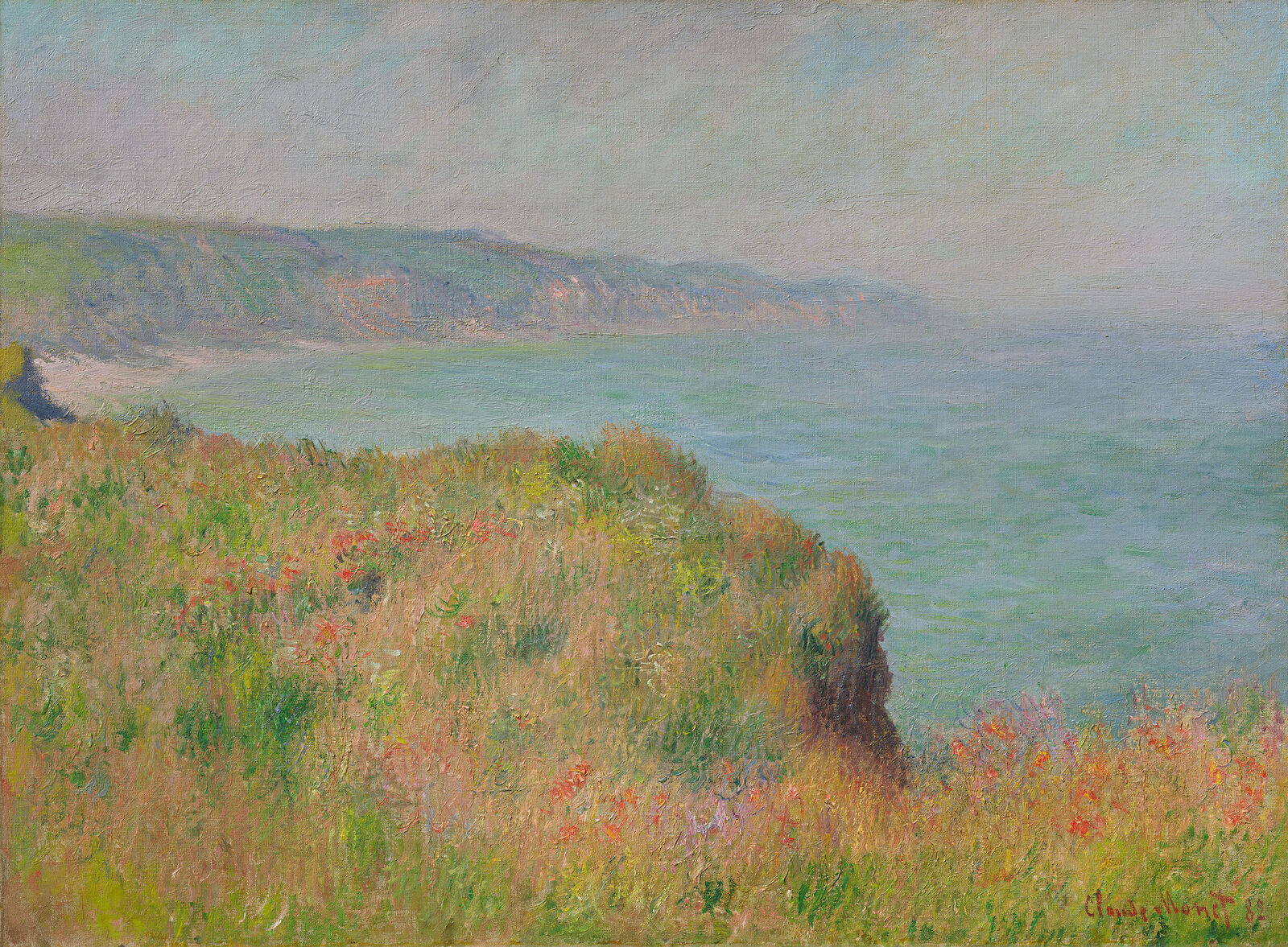

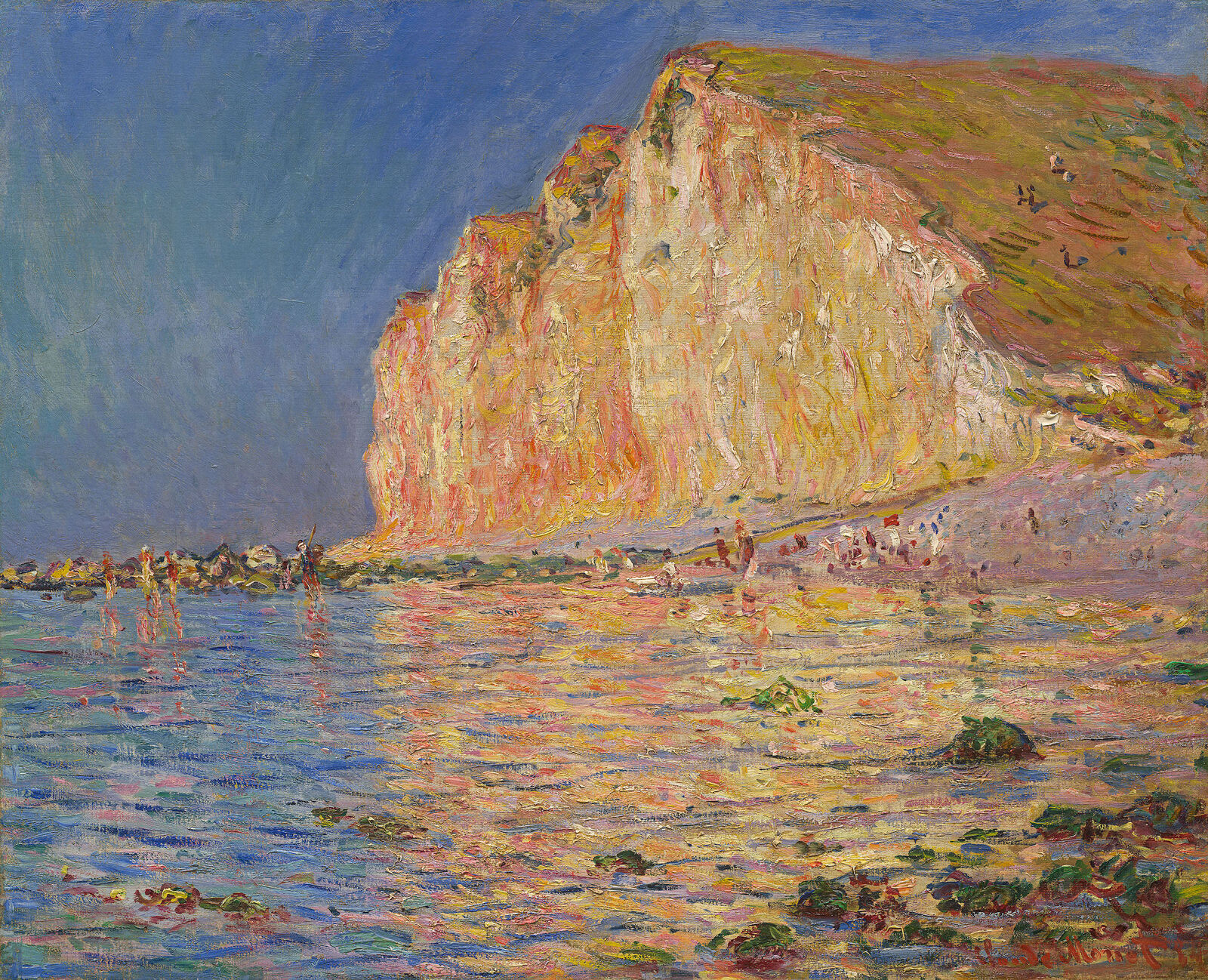

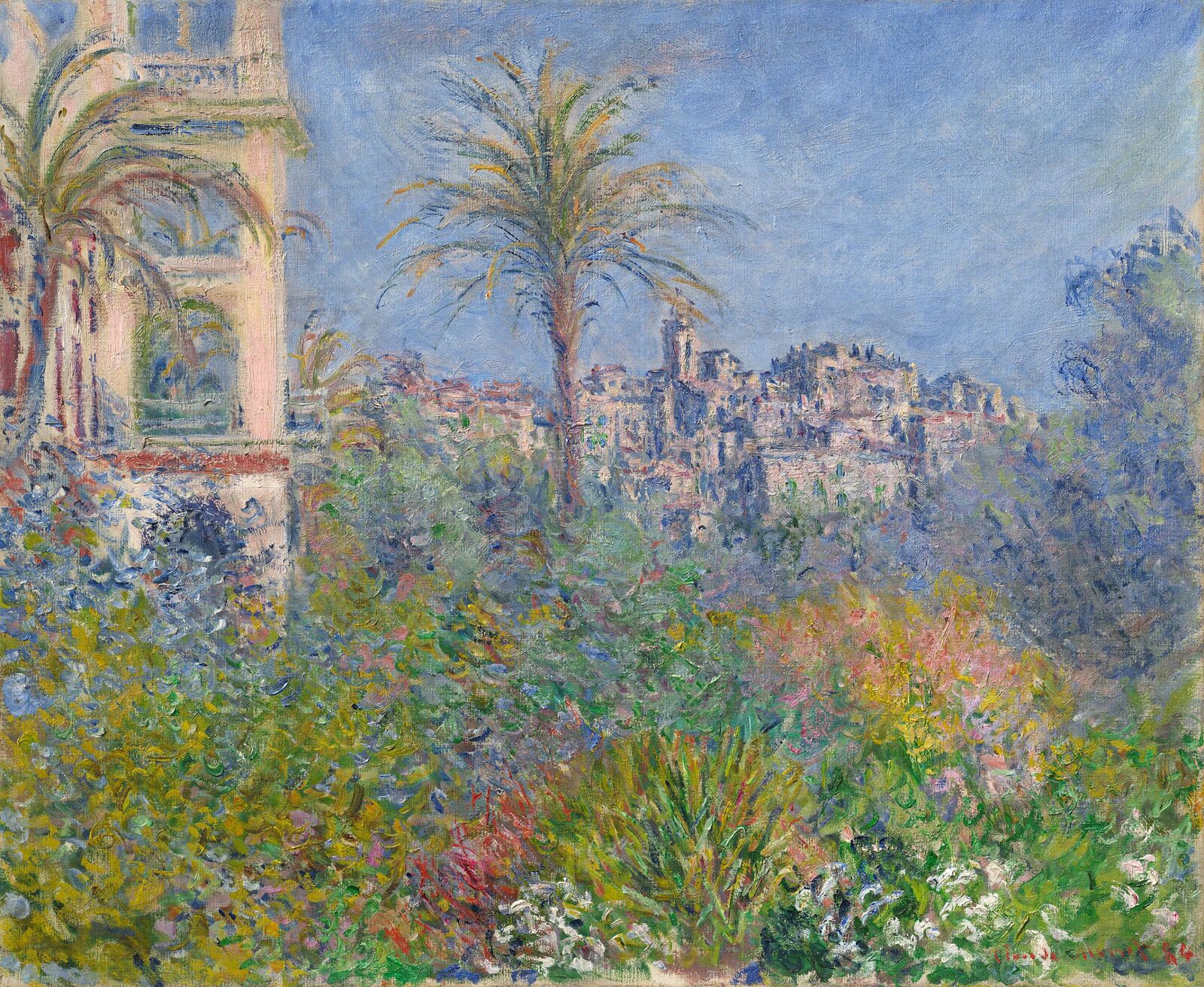

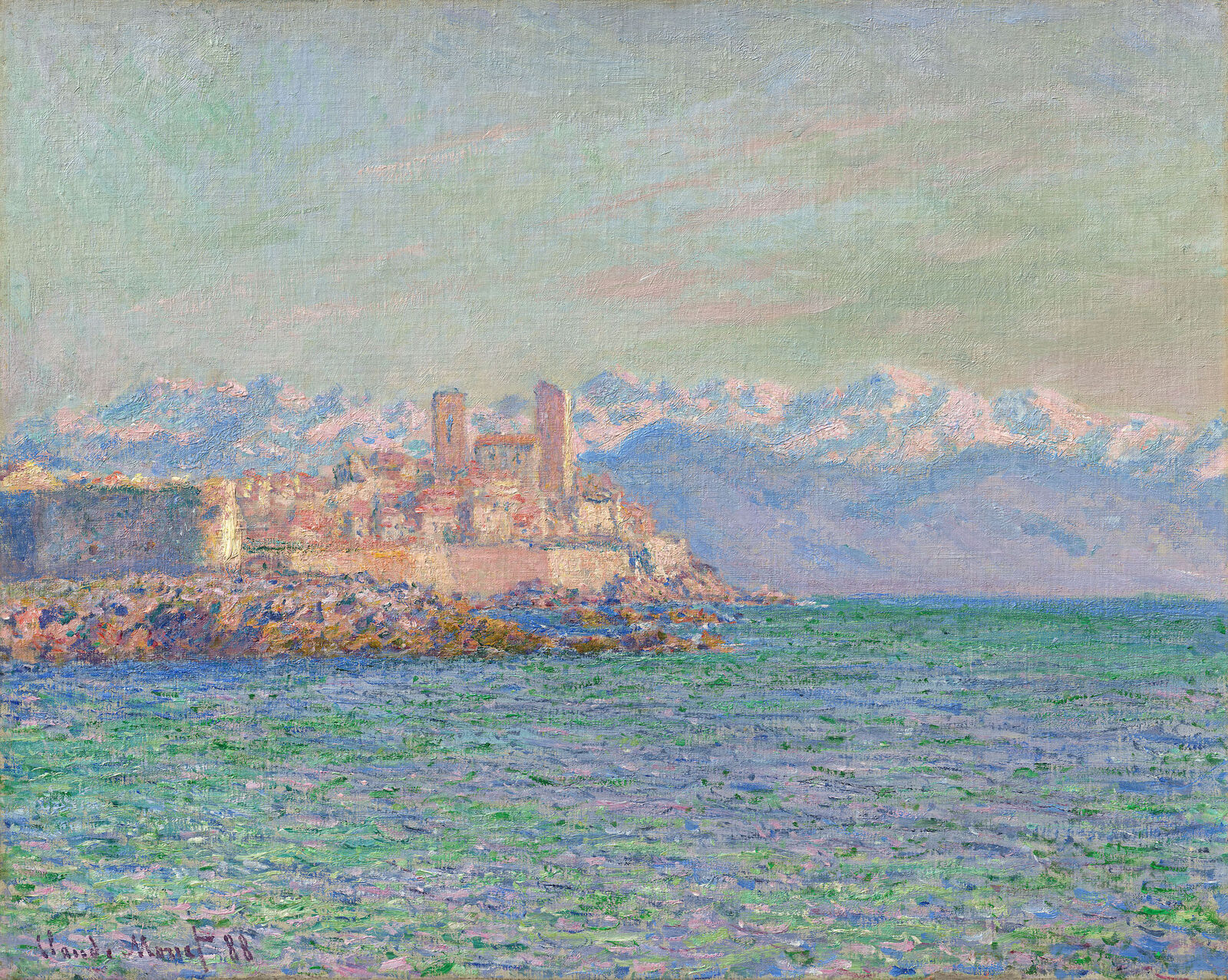

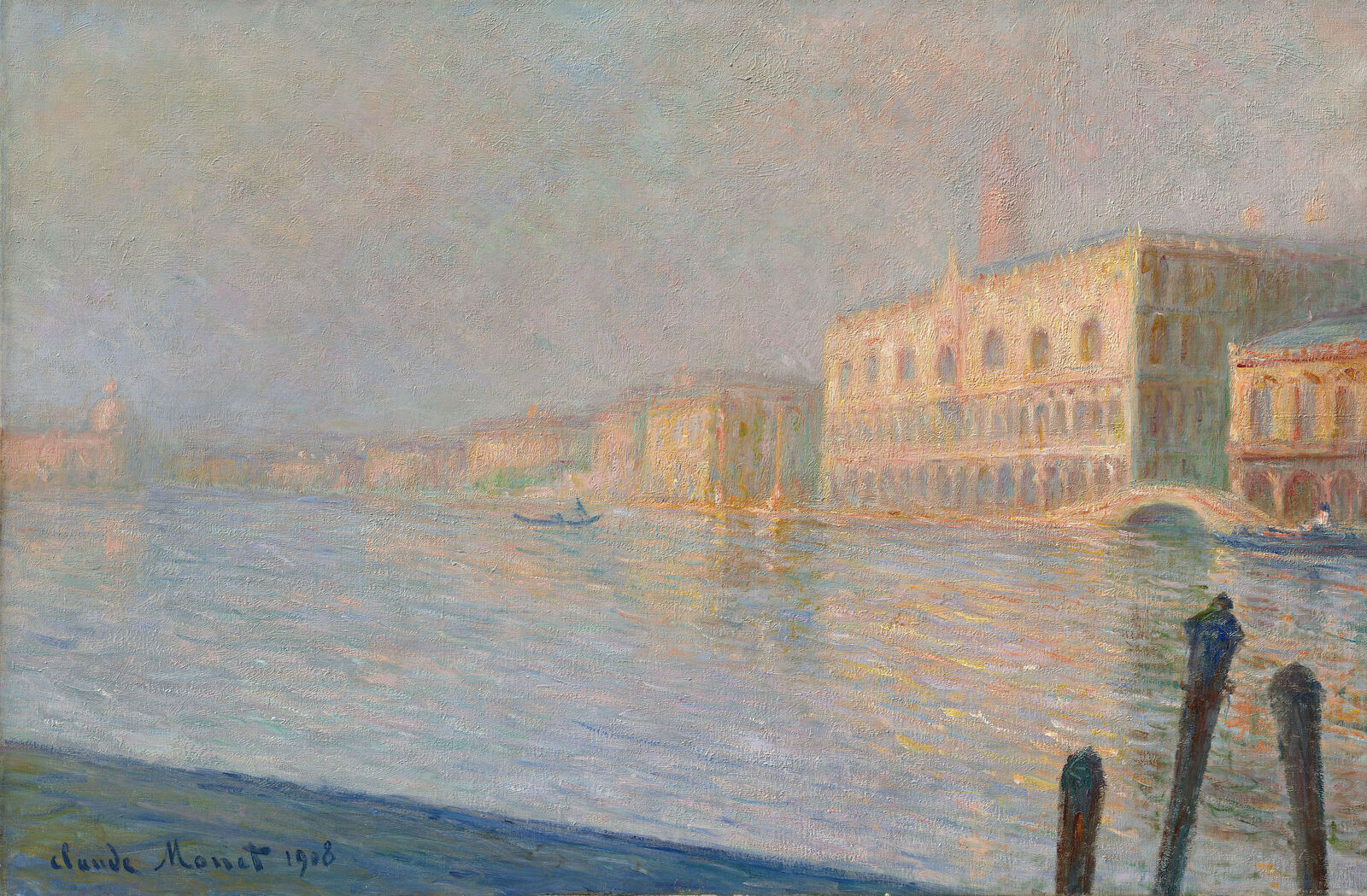

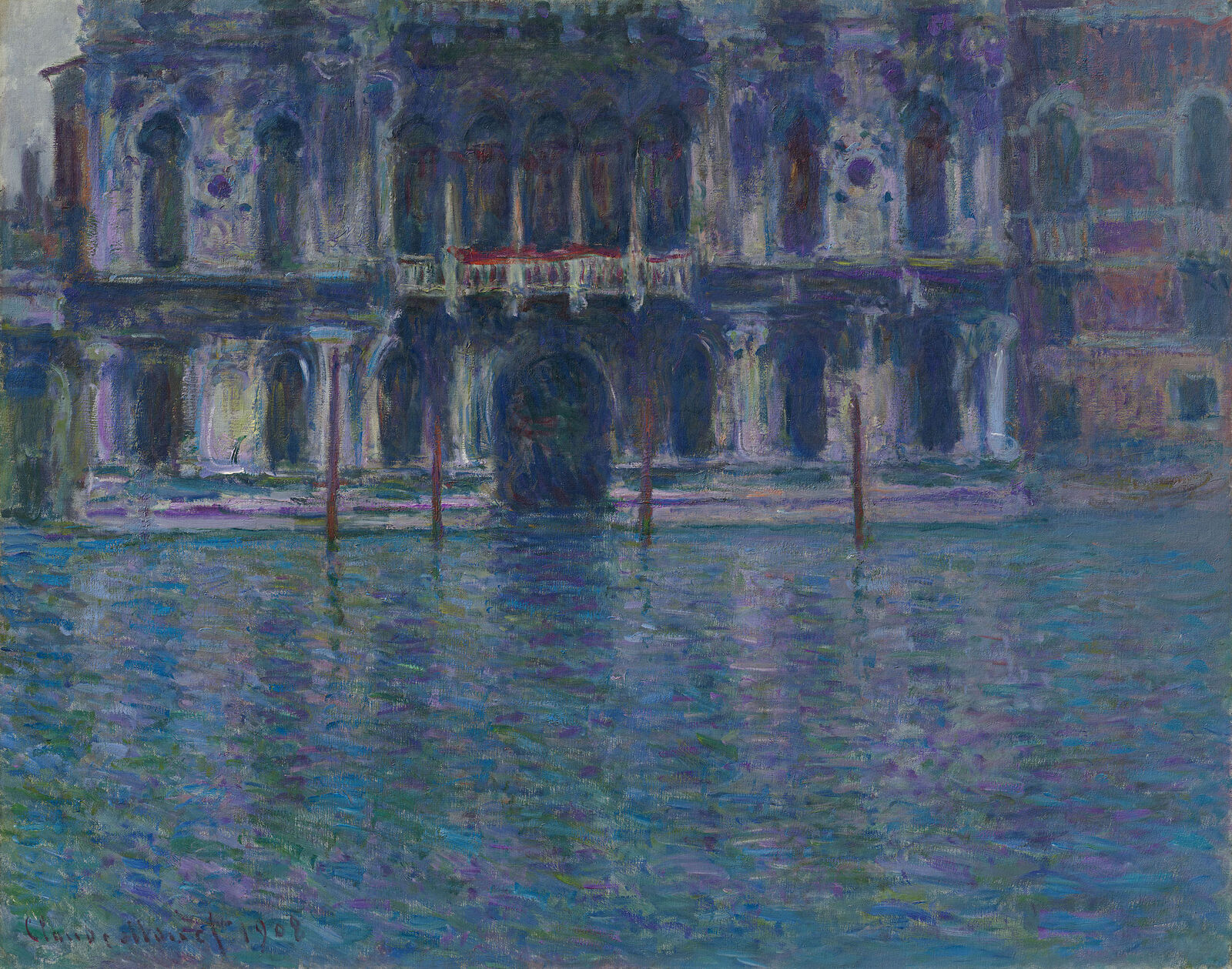

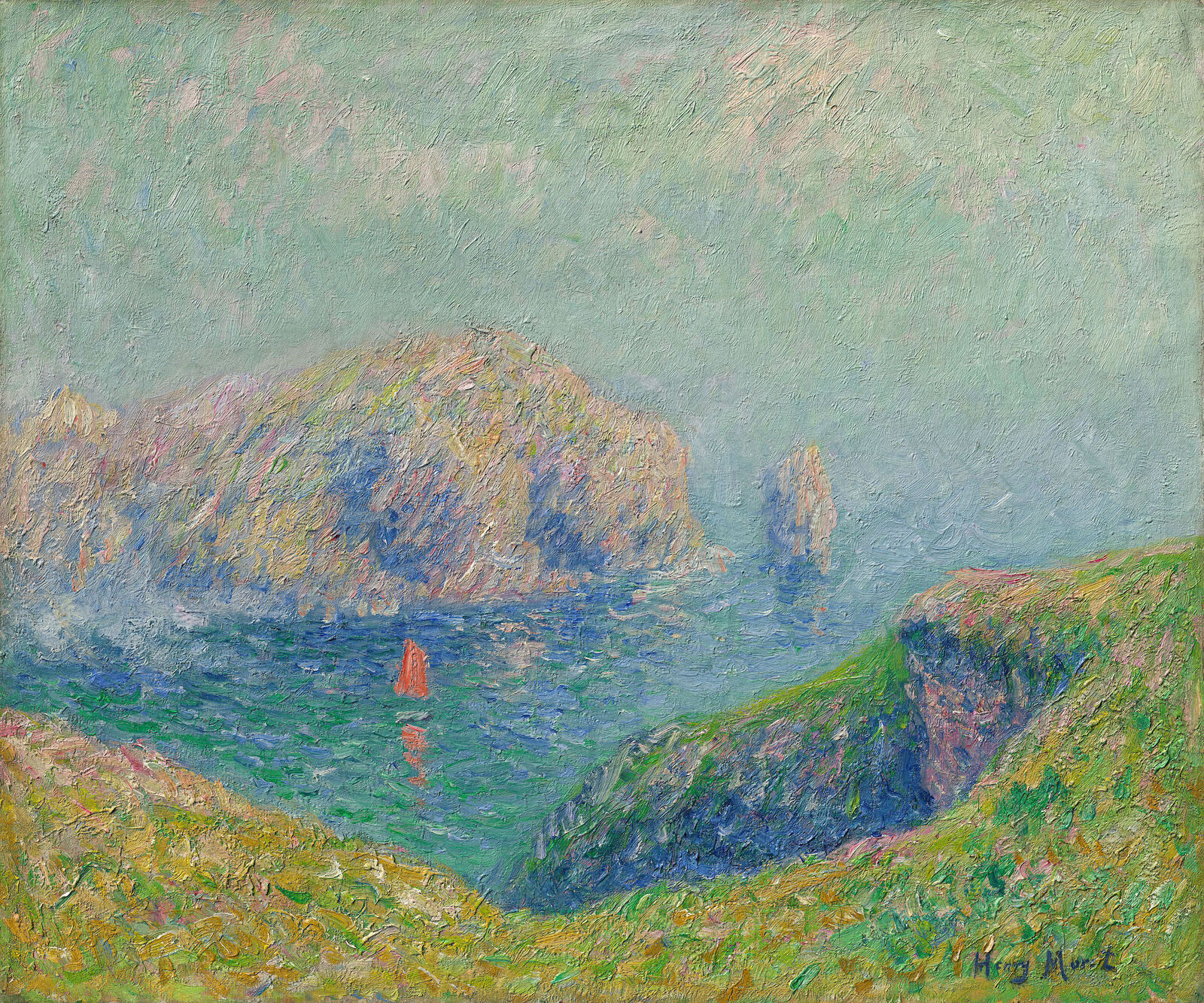

Monet’s generation no longer went to Italy to study antiquity. The observation of nature at home had replaced classical landscape painting. Like other tourists, the artists traveled by train to explore the coasts of northern and southern Europe. They painted in the French Riviera, in Venice and Saint-Tropez, at the cliffs of Brittany, or in the Italian Riviera.

In the late 19th century, the coastal landscapes of Europe became increasingly popular among tourists and were marketed through postcards. Artists responded to this competition by adopting the cropping techniques of photography. Their impasto painting formed a counterpoint to the smooth finish of this new visual medium.

Many painters followed in Monet’s footsteps and traveled to the Mediterranean.

Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross moved there in the 1890s and continued to develop Pointillism in the French Riviera. In the southern light, they created almost paradisiacal landscapes imbued with the ideal of peaceful coexistence in unspoiled nature.

By a methodical divisionism … and a strict observation of the scientific theory of colors, Neo-Impressionism insures a maximum of luminosity, of color intensity, and of harmony …

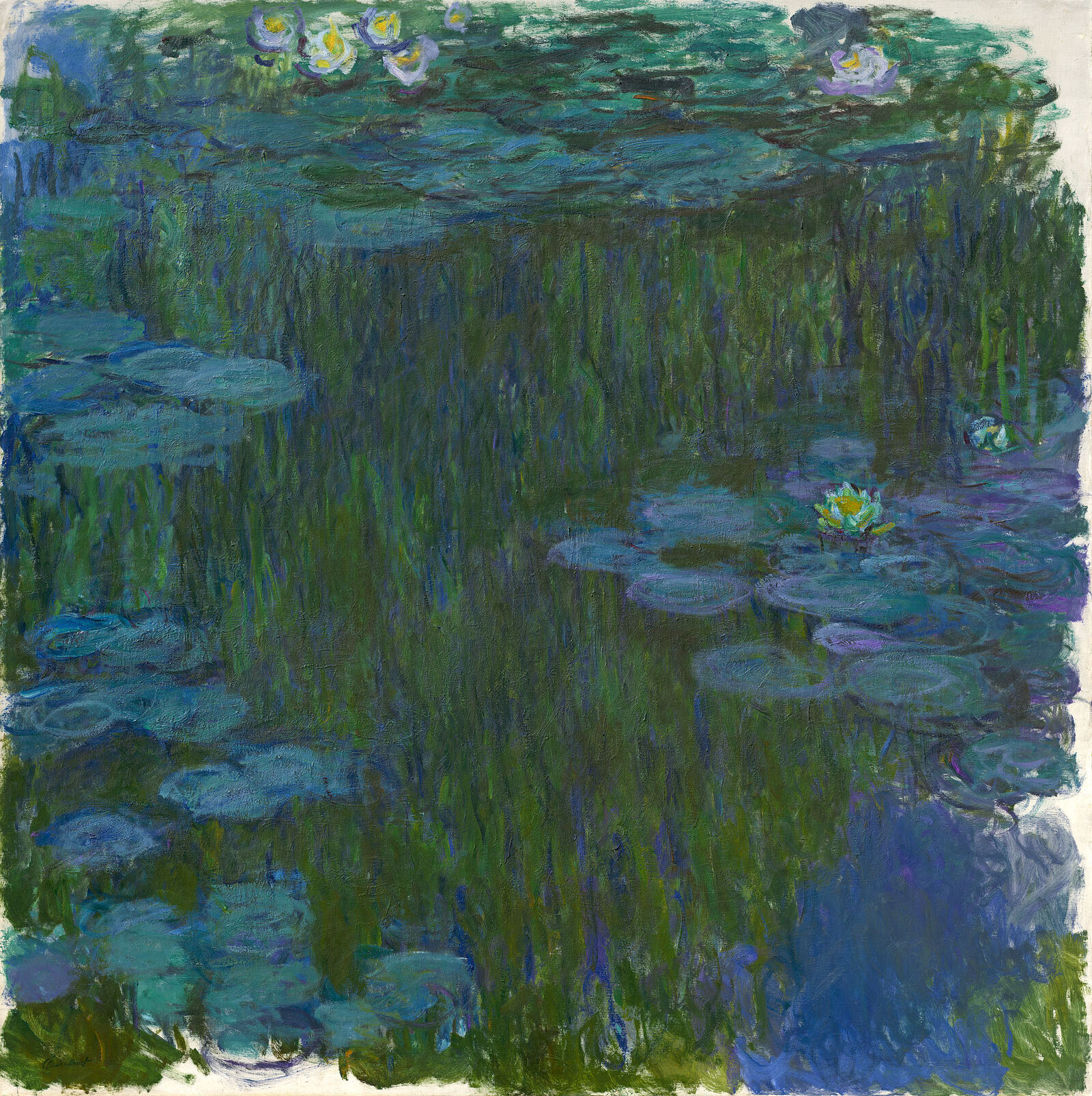

Claude Monet: The Water-Lily Pond, ca. 1918

Hasso Plattner Collection

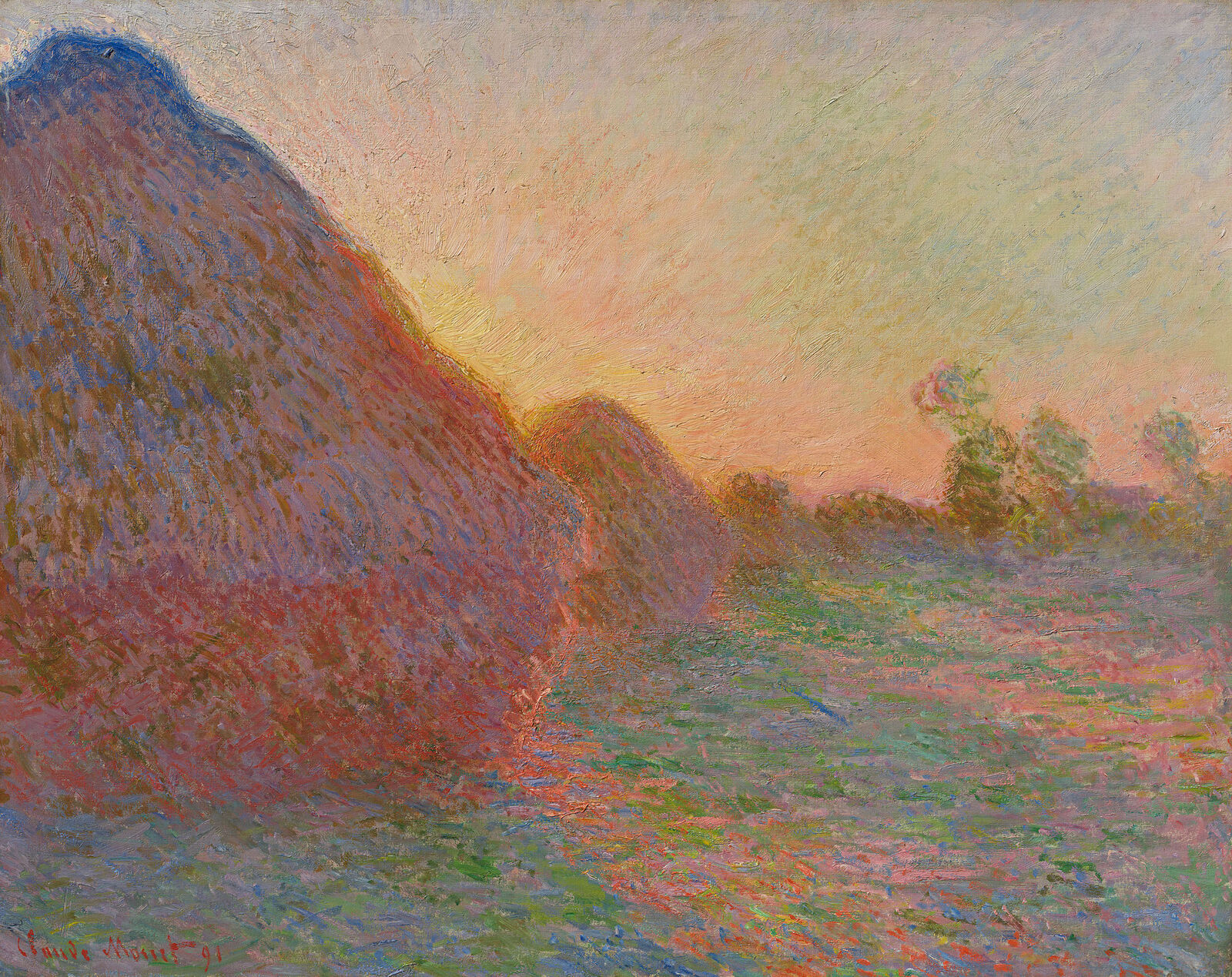

Monet’s intensive study of the changing seasons and times of day prompted him to adopt a completely new artistic concept. He pursued the idea of capturing specific moments through the repetition of a motif.

He began exploring this approach after leaving Paris in the late 1870s and moving to a rural environment. In particular, the region around Giverny and his own garden of water lilies offered Monet a perfect setting to create works in series.

Monet’s very first series consisted of 25 paintings of grainstacks, which he systematically depicted under varying conditions of light and weather.

From 1891 on, the artist showed extensive series of works at the Galerie Durand-Ruel in Paris, with numerous variations of a single motif. Three of these famous groups of works are represented with examples in the Hasso Plattner Collection. Monet’s grainstacks were followed by series devoted to the cathedral of Rouen and later to the Houses of Parliament in London, and finally to his water lily pond in Giverny.

It took me some time to understand my water lilies.… I grew them with no thought of painting them.… And then, all at once I … reached for my palette. I’ve hardly had any other subject since that moment.

Hasso Plattner Collection

Claude Monet: Houses of Parliament, Sunset, 1900–1903

In London, Monet was fascinated by the interplay of the luminous surface of the water and the imposing architectural forms. During three visits to London between 1899 and 1901, the painter focused his attention on the silhouette of Westminster Palace in the smog at sunset.

Auguste Herbin: Landscape on Corsica, 1907

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

In 1905, a radically new art movement emerged in France, with works marked by brilliant, expressive colors and bold contours. At their first exhibition at the Salon d’Automne in Paris, the painters were dubbed “Les Fauves” (the wild beasts) by an art critic. Among the artists were André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Auguste Herbin.

The Fauves distanced themselves from Impressionist and Pointillist painting. Their focus was no longer on reproducing fleeting phenomena of nature, but on the pure expressive power of color—a radical step in the direction of abstraction.

Maurice de Vlaminck: Rueil, the Boathouse, 1906

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Bridge at Chatou, 1906/07

Maurice de Vlaminck: Saint-Michel District, Bougival, 1913

Maurice de Vlaminck: Landscape with Red Roofs, o. J.

But the Fauves’ emphatically expressive, emotionally charged, and brilliantly colored style did not prevent them from painting the same motifs as the Impressionists and Pointillists. While André Derain followed in the footsteps of Cross and Signac in the South of France, Maurice de Vlaminck painted in Bougival—a town on the Seine where Renoir and Monet had found their subject matter already in the 1860s.

Hasso Plattner Collection / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Forest, 1914–18

Vlaminck was the only one of the Fauves who was happy to be described as “wild.” His conscious intent was to shatter traditional conventions; yet at the same time, his vehement painting also shows the influence of Cézanne. The three generations of artists—Impressionists, Pointillists, and Fauves—all shared the same ideal: to evoke the sensory experience of nature through light and color.