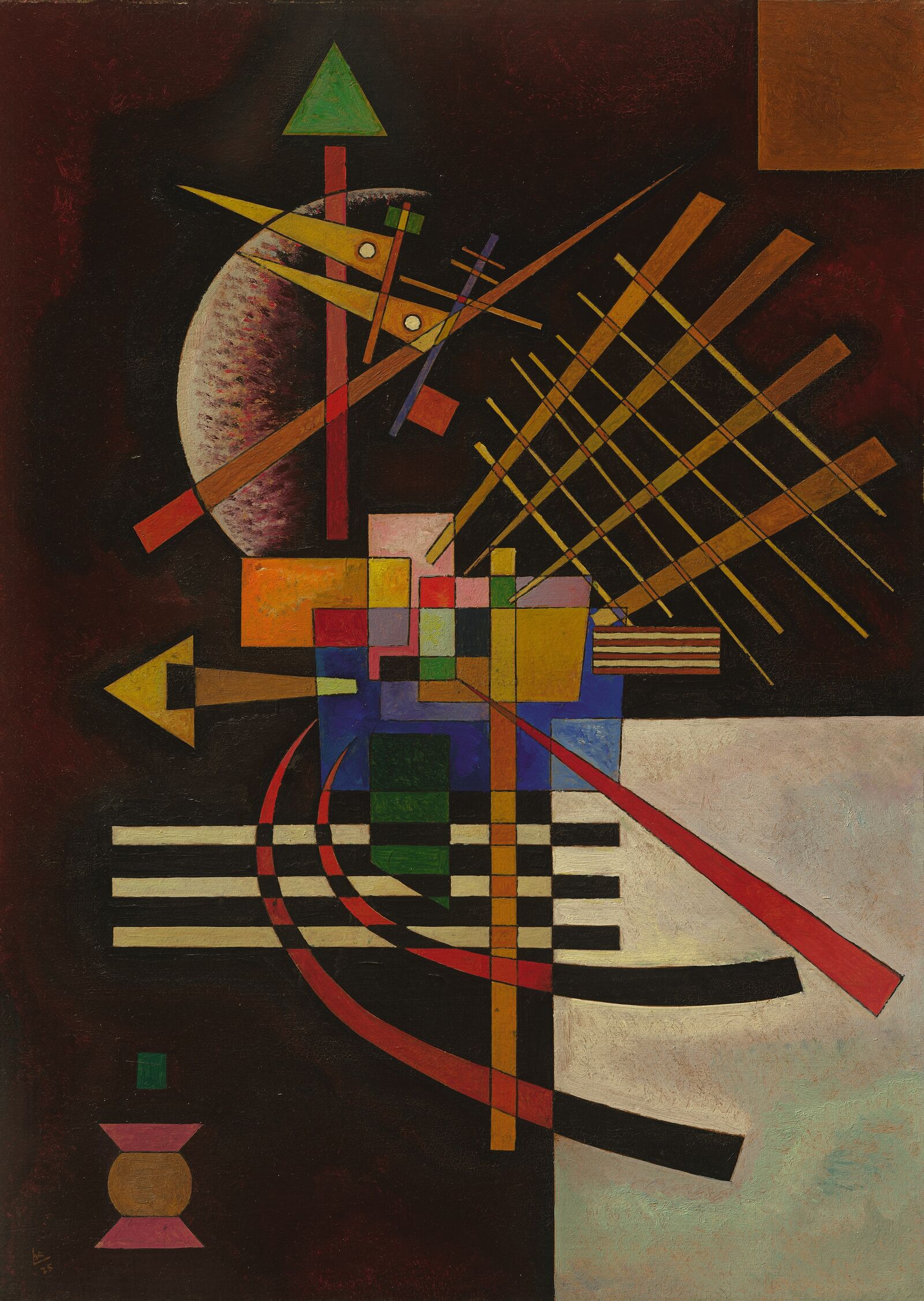

Kandinsky's Universe

Is geometric abstraction just squares and circles, points and lines, with no meaning or message? A kind of impersonal decoration, a monotonous art of little boxes? Not at all! A closer look at the history of this artistic approach shows just how multifaceted the ideas behind these seemingly repetitious forms are and how much they can tell us about their times.

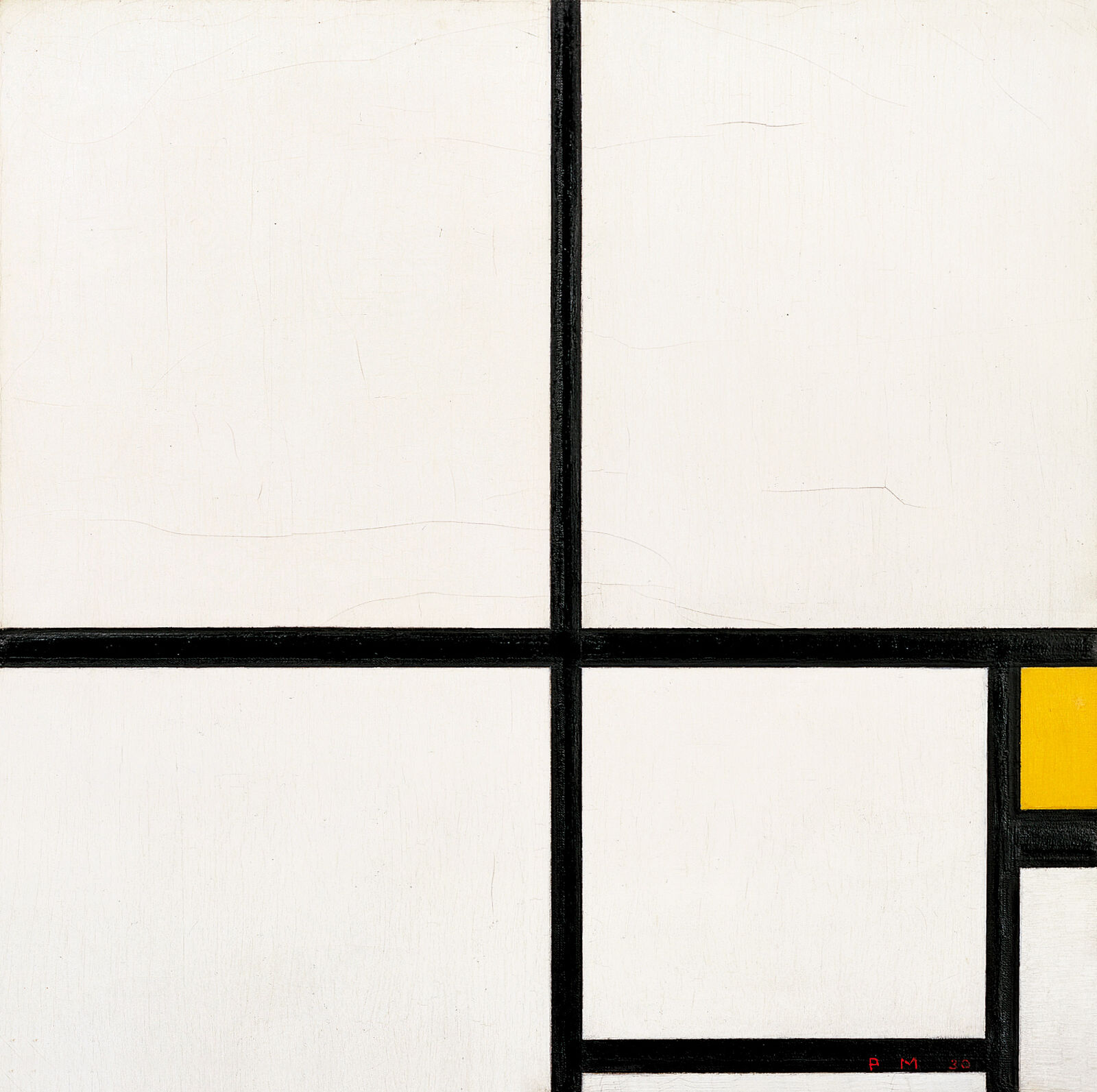

Piet Mondrian: Composition With Yellow, 1930, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

The square is one of the primary forms ...

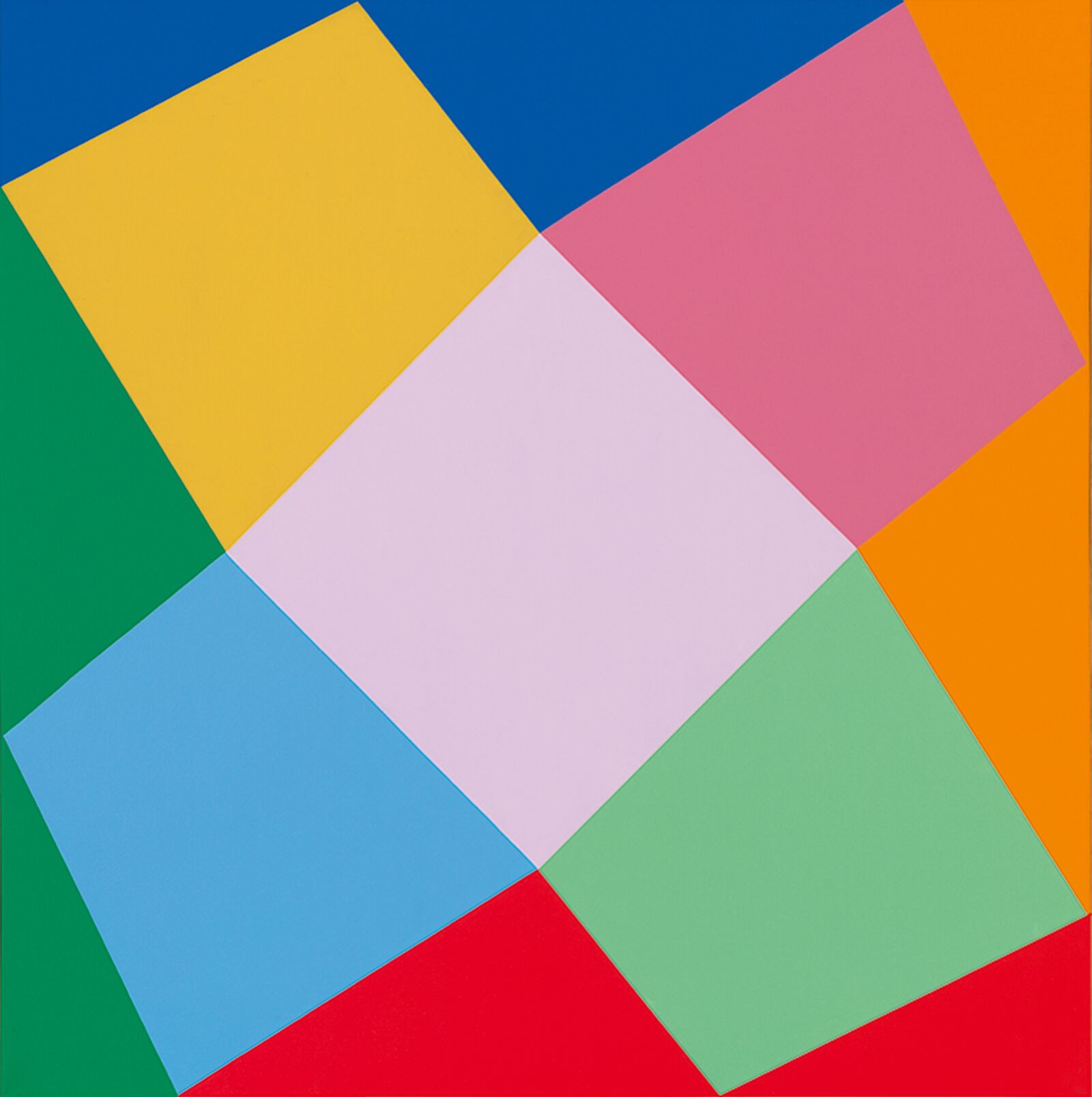

Verena Loewensberg: Untitled, 1965, Private Collection, Switzerland, Courtesy of Henriette Coray Loewensberg, Verena Loewensberg Estate Zurich

Photo: Philipp Hitz

... abstract artists have explored over the course of generations.

The dawn of geometric abstraction in the early twentieth century coincided with the rise of the modern age. This new epoch, shaped by technological progress and scientific discoveries, called for an art that was no longer limited to representation of the visible world. The task of mimetically depicting reality had been taken over by photography and film, leaving art free to follow new paths. While countless cultures throughout the millennia had employed abstract patterns, it was not until around 1910 that artists discovered geometric form as an autonomous pictorial subject. For them, abstraction offered an opportunity to pursue spiritual ideas and explore immaterial worlds.

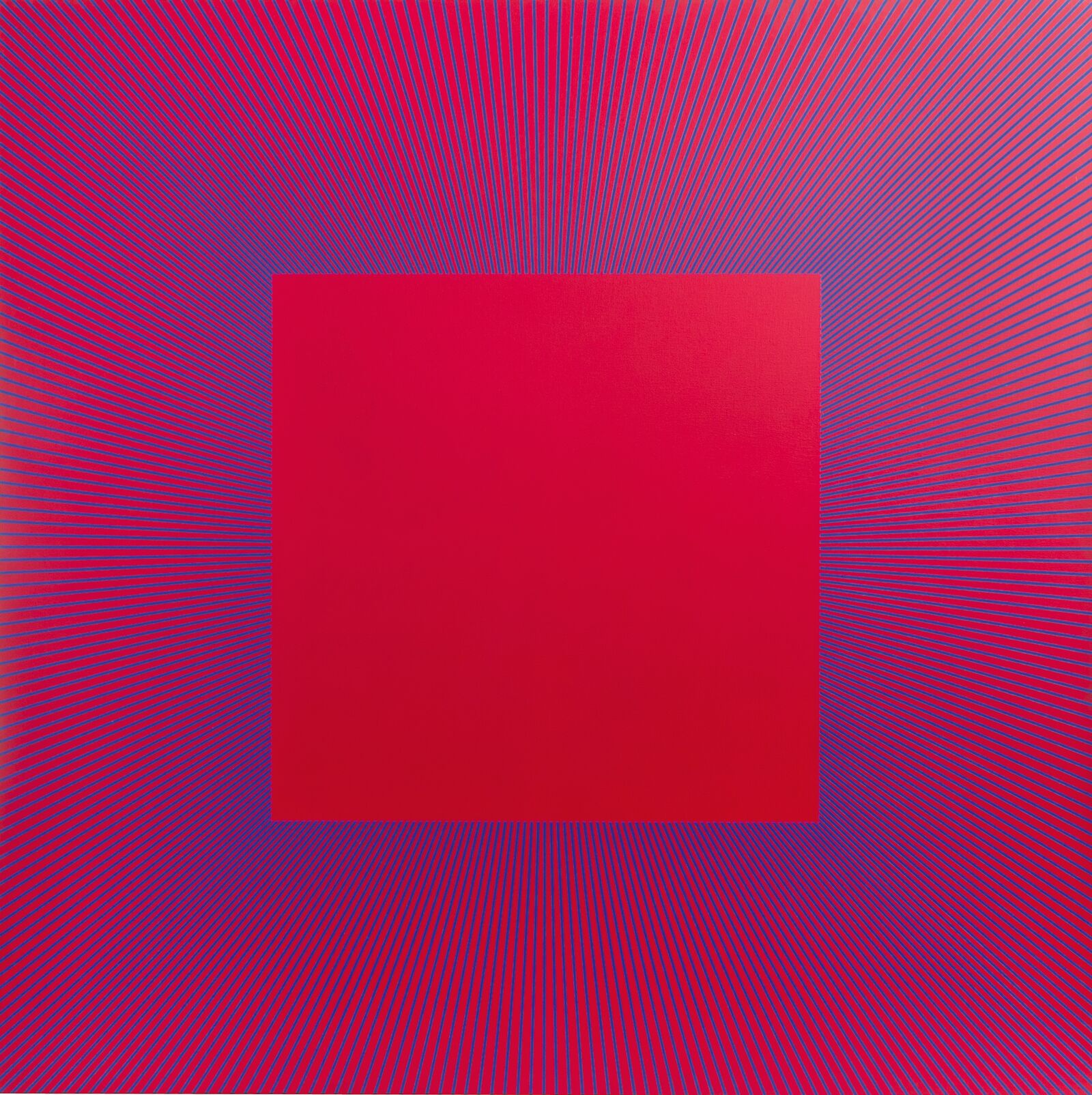

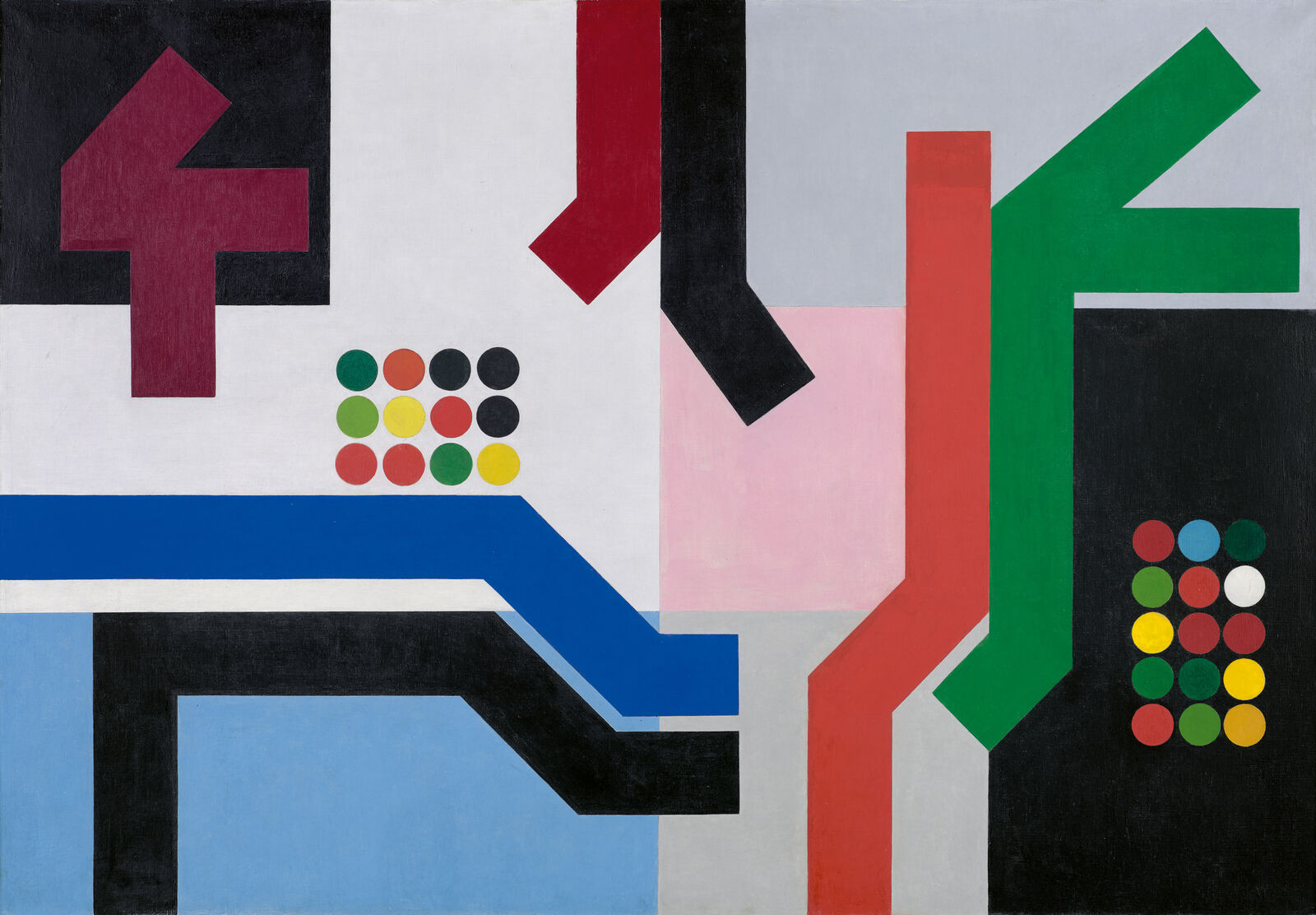

Richard Anuszkiewicz: Metamorphosis Of Cadmium Red - Blue Line, 1979, The Estate of Richard Anuszkiewicz, VG-Bild Kunst, Bonn 2025

Photo: The Loretta Howard Gallery

Like his teacher, the former Bauhaus master Josef Albers, Richard Anuskiewicz adopted the square as a geometric framework.

Kandinsky – Pioneer and Teacher of Abstraction

Born in Moscow in 1866, Wassily Kandinsky was a pioneer of abstraction. In Murnau in Bavaria, he liberated color with his expressive approach to painting before shifting to pure abstraction in 1913. His early “Impressions,” “Improvisations,” and “Compositions” of biomorphic forms were inspired by modern music. Based on his own experience of synesthesia, he also studied the effects of nonrepresentational forms and colors in his theoretical writings, publishing his groundbreaking treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art in 1911. As a teacher, Kandinsky shared his insights with the next generation in Moscow, at the Bauhaus in Weimar, and finally in Paris. All the while, he remained open to new influences and continued to develop his personal abstraction until his death in 1944.

Form itself, even if completely abstract, resembling geometrical form, has its own inner sound, is a spiritual being possessing qualities that are identical with that form.

Ljubow Popowa: Spatial Force Construction, 1920/21, MOMus - Museum of Modern Art - Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

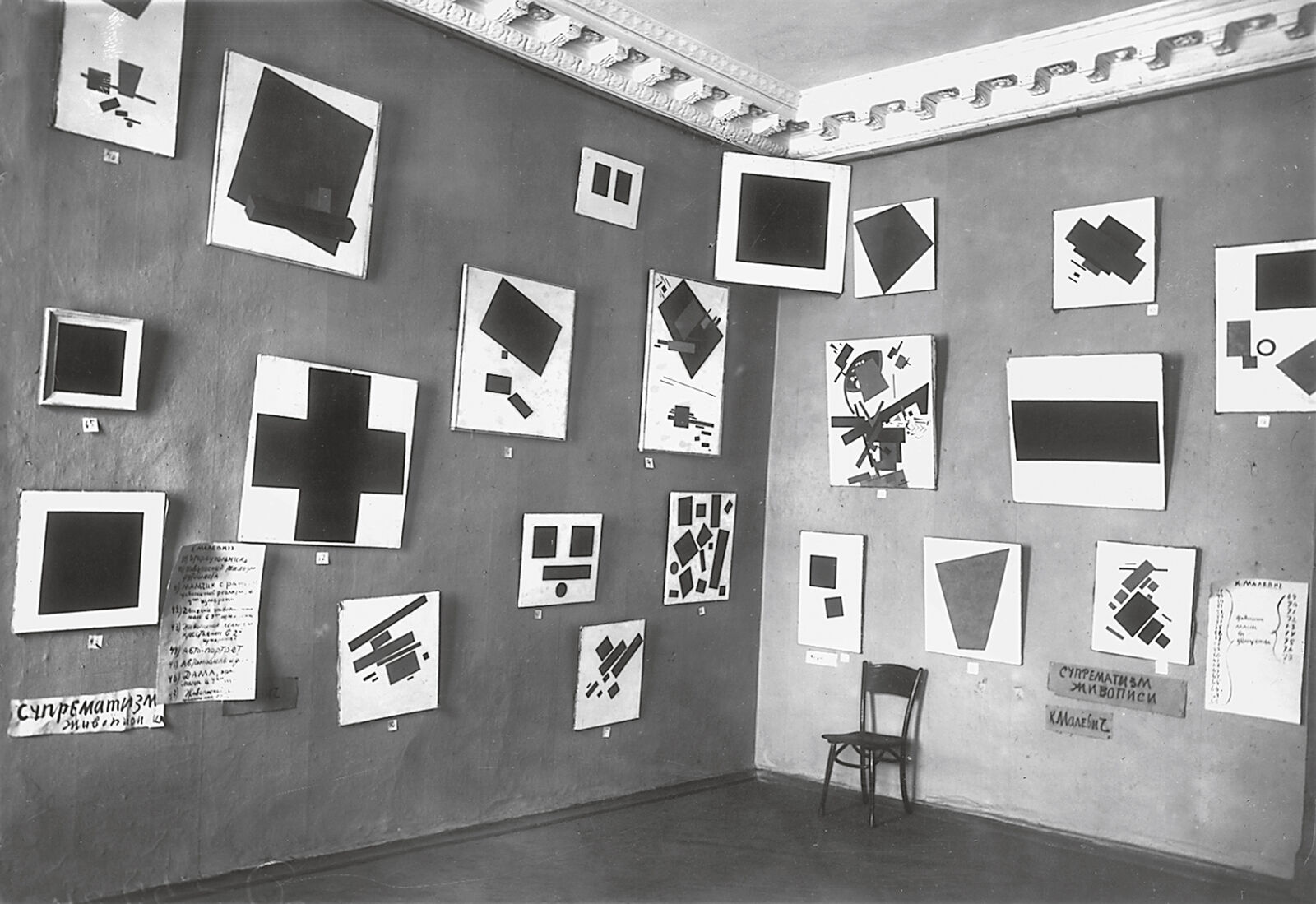

In its early days, geometric abstraction was often met with rejection. In the winter of 1915, visitors to an exhibition in St. Petersburg were shocked to see a painting by Kyiv-born artist Kasimir Malevich that consisted of nothing but a black square on a white ground. The work constituted a tabula rasa: an end, and at the same time a new beginning for painting. Malevich replaced the horizon and the blue sky of a landscape with a light background, against which simple geometric forms seemed to float. He confidently called this radical new art “Suprematism”—from the Latin word supremus, the highest—believing that would it lead humanity to new realms of knowledge.

Exhibition view of 0.10 - The last futuristic exhibition of painting, St. Petersburg 1916

The photograph shows the Suprematist works exhibited by Malevich in St. Petersburg in 1915. The black square on a white ground was mounted in the upper corner of the room—the location usually reserved for a religious icon in an Orthodox household.

In my desperate attempt to free art from the ballast of objectivity, I took refuge in the square form.

In 1917, the October Revolution brought an end to the era of tsarist rule. Under Lenin’s leadership, the Bolsheviks appointed Malevich and other avant-garde artists to positions within the newly founded cultural institutions of the state. The revolutionary spirit was pervasive: Malevich’s supporters called themselves the “Champions of the New Art.”

El Lissitzky: Untitled, 1919/20, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venedig (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York)

Lasar Lissitzky, known as El Lissitzky, pursued studies in architecture before turning to Suprematism and Constructivism as an artist.

This environment also gave rise to the Constructivist movement, spearheaded by Alexander Rodchenko. Pursuing his art like a science, Rodchenko investigated the possibilities of line and the expansion of color in series of works. Constructivism adopted terminology from the fields of engineering and science: composition was replaced by construction as a principle of artistic design, while subjective creation yielded to collective production. In this way, the Constructivists sought to contribute to the formation of a new, socialist society.

Alexander Rodtschenko: Lineism, 1920, MOMus - Museum of Modern Art - Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

The work Lineism resulted from a systematic exploration of the individual elements of painting—here, the functions of line.

Ljubow Popowa; Painterly Architectonics, 1918/19, MOMus - Museum of Modern Art - Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

Lyubov Popova’s introduction to abstraction came through Cubism, which she had encountered during her student days in Paris.

Kandinsky and Communism

The theoretical foundations of Constructivism were developed at the Institute for Artistic Culture (INKhUK), where Wassily Kandinsky served as director until early 1921. Although the Russian artist had lived in Bavaria since 1896, he had to leave the German Kaiserreich at the outbreak of World War I. Back in Moscow, he integrated elements of contemporary art movements and enriched his organic, cipher-filled abstraction with geometric forms from the repertoire of Suprematism and Constructivism. But Kandinsky resisted the ideological discussions at INKhUK and the pressure to objectify art, and in late 1921 he returned to Germany.

Ilya Chashnik: Suprematist Cross, 1923, MOMus - Museum of Modern Art - Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

Ilya Chashnik’s teachers included not only El Lissitzky, but also Kasimir Malevich, for whom he worked as a student assistant from 1923 to 1926.

Wassily Kandinsky: White Cross, 1922, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York)

In Wassily Kandinsky’s painting White Cross, the use of black and white as well as simple geometric shapes alludes to the Suprematism of Kasimir Malevich.

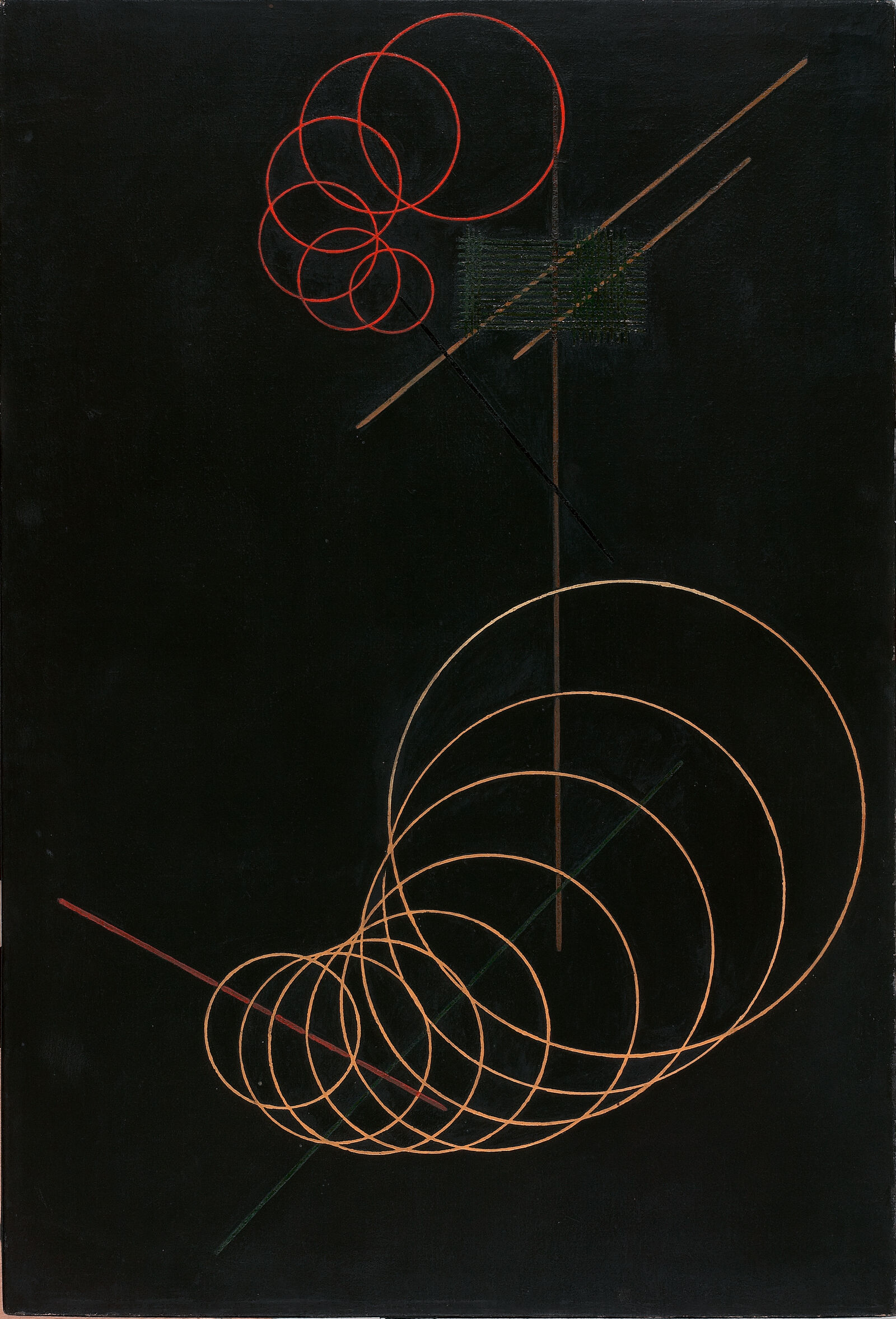

László Moholy-Nagy: Composition Z VIII, 1924

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin — Neue Nationalgalerie

In 1922, Kandinsky became an instructor at the Bauhaus. Founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919, the school taught fine and applied art on equal footing. In addition to courses on photography and architecture, there were workshops for stained glass, weaving, and ceramics. The Bauhaus quickly became a point of attraction for modern artists far beyond the borders of the Weimar Republic. Among its teachers—who were also called masters—were the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy and the Swiss artist Johannes Itten.

Johannes Itten: Sticks and Planes, 1955, Mercedes-Benz Art Collection, © Andreas Freytag, Stuttgart, VG Bild-Kunst, 2025

Johannes Itten developed the foundations of his color theory during his time at the Bauhaus in Weimar.

The point is a small world cut off more or less equally from all sides and almost torn out of its surroundings. ... Only its concentric tension discloses its inner kinship with the circle—while its further characteristics rather point to the square.

Wassily Kandinsky: Emphasized Corners, 1923, Nahmad Collection

In Kandinsky’s view, the “inner sound” of colors predisposed them to assume certain forms: yellow was correlated with the acute angle and the triangle, red with the right angle and the square, and blue with the obtuse angle and the circle.

The unadorned Bauhaus style, defined by functionality, found an echo in Kandinsky’s abstraction. His works from the 1920s seem more controlled, more structured. During his time at the Bauhaus he also published a second programmatic text, Point and Line to Plane of 1926, which explored the foundational elements of art.

The geometric line is ... the track made by the moving point; that is, its product. It is created by movement—specifically through the destruction of the intense self-contained repose of the point. Here, the leap out of the static into the dynamic occurs.

Abstraction under Pressure

In 1925, the Bauhaus moved to Dessau. With the rise of National Socialism, however, the progressive art school increasingly came under pressure, and after a brief stint in Berlin the Bauhaus closed its doors for good in 1933. Just as in the Soviet Union, where abstraction was now rejected as formalistic, nonobjective art was targeted by the cultural policies of totalitarian Nazi Germany. The crusade against abstraction culminated in the show Degenerate Art of 1937, which included abstract works by Kandinsky. By this time Kandinsky, who had obtained German citizenship in 1928, was already in France.

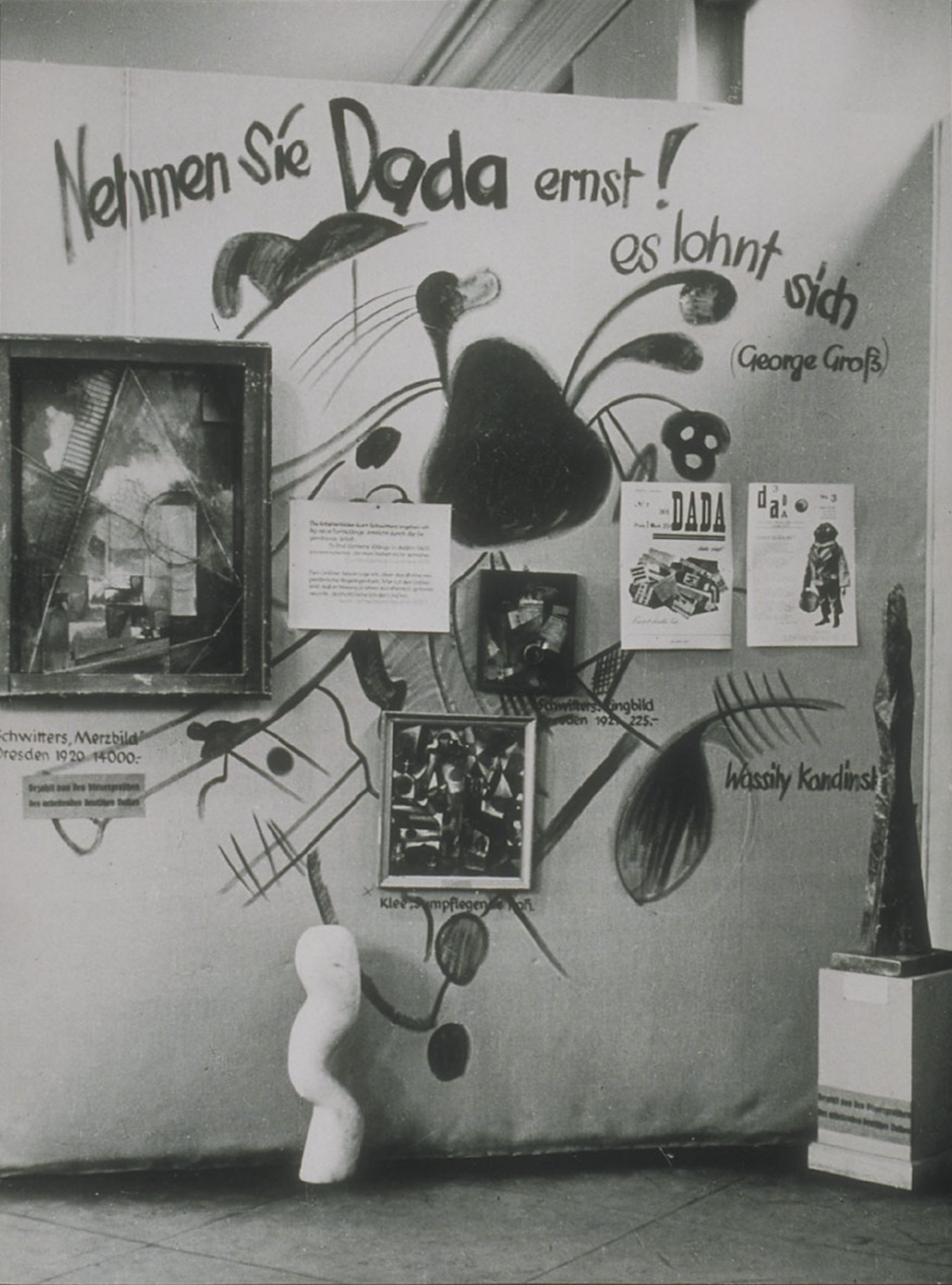

Exhibition „Entartete Kunst“, Photo by Erich Andres, Munich 1937, © Staatsarchiv Hamburg, Foto: Erich Andres, 720-1/343-1/A24_56_10

The propaganda show Degenerate Art, exhibited at the Hofgarten Arcades in Munich in 1937, displayed over 600 works vilified as “degenerate” by the Nazi regime, including abstract pictures by Kandinsky. On the so-called “Dada wall,” the organizers also painted an image resembling Kandinsky’s Black Spot of 1921.

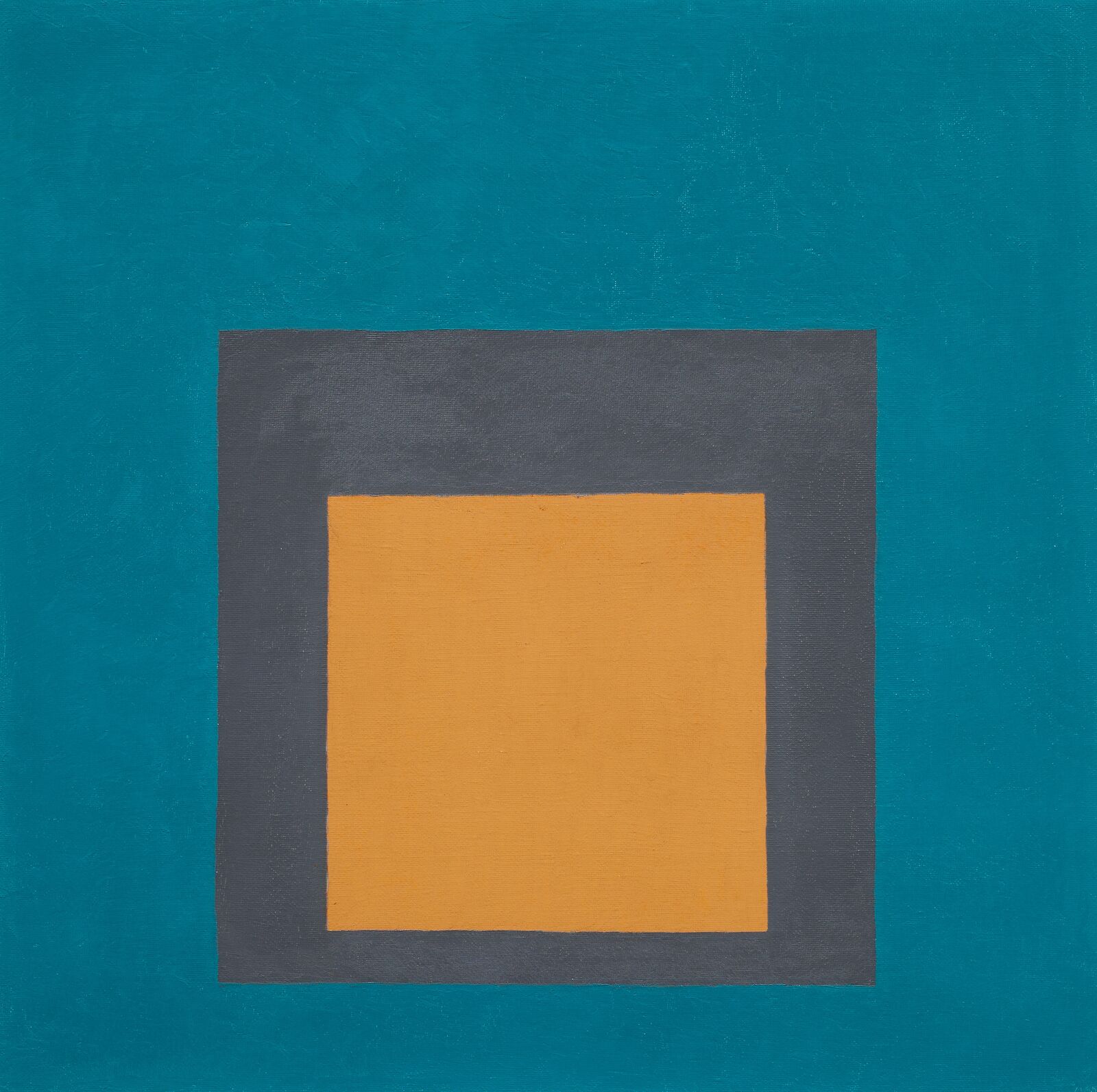

The forced closure of the Bauhaus was not the end of the story: former teachers and students from the school spread its ideas and aesthetic throughout the world. Josef Albers, for example, went to Black Mountain College in the United States, where he used the square to convey his insights on the perception of color. In Zurich, the Swiss artist Max Bill, a former student of Kandinsky, helped found the Concrete Art movement, which called for the rejection of all references to the material or spiritual world.

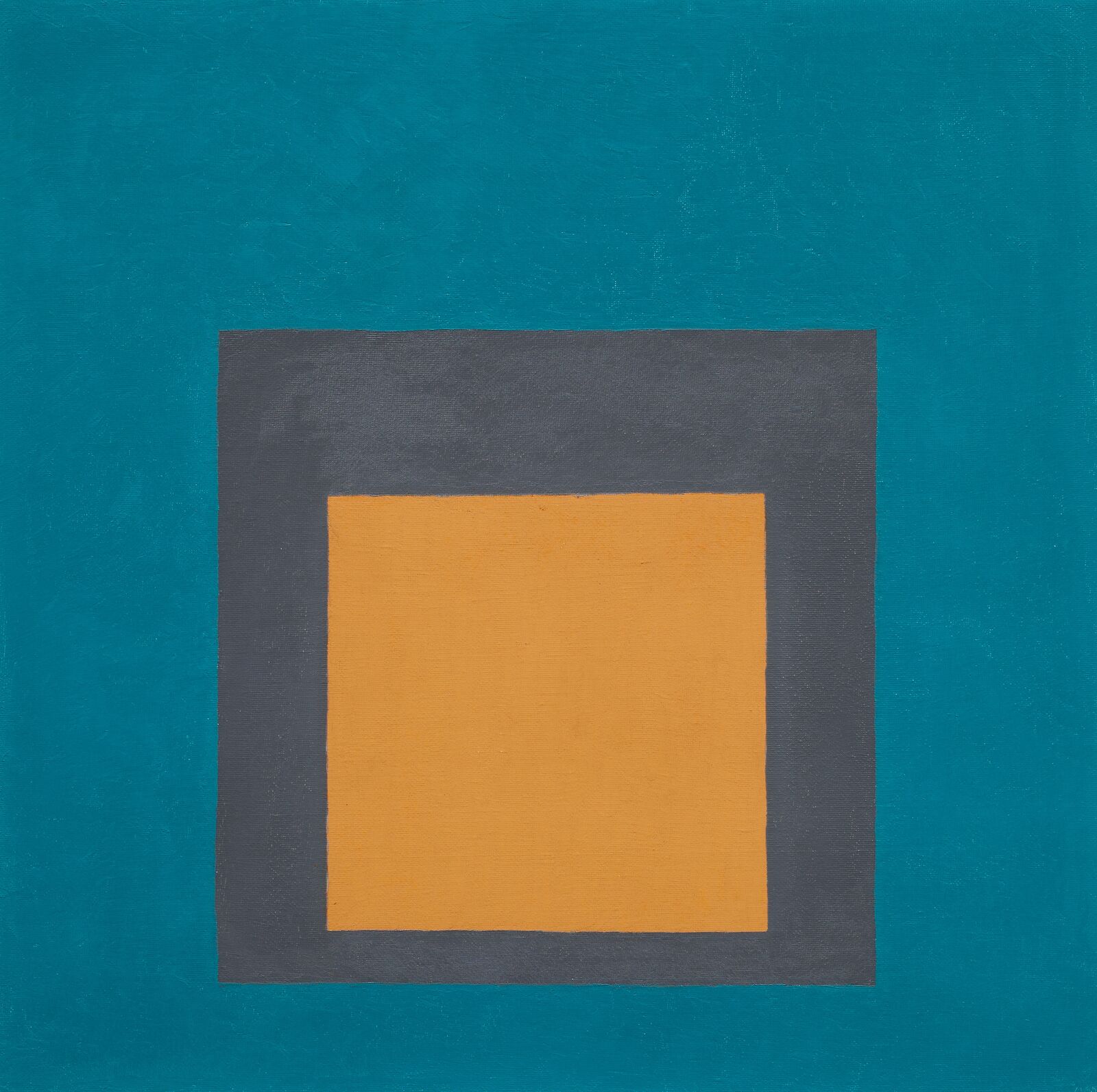

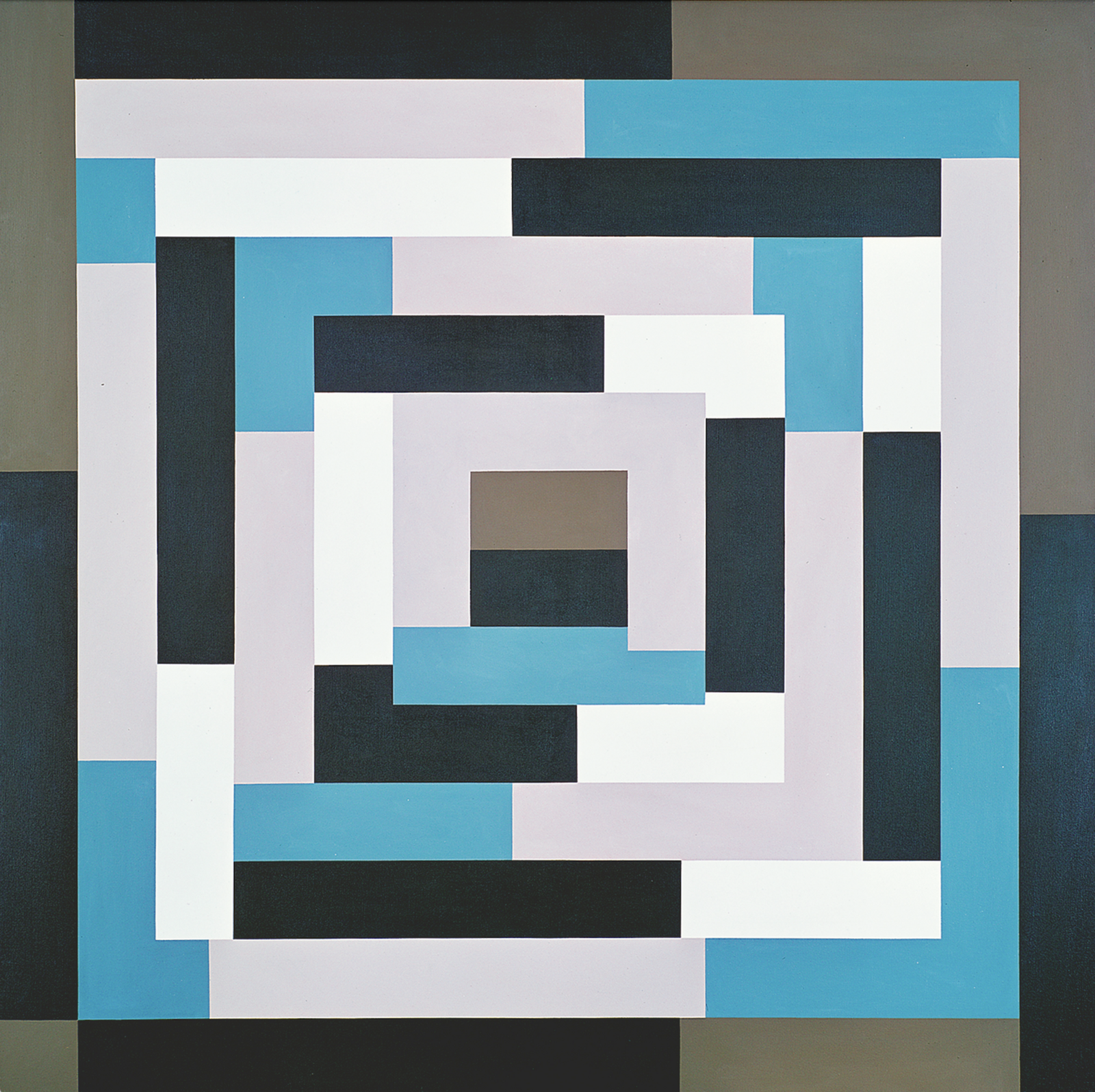

Josef Albers: Study for Homage to the Square, 1965, Josef Albers Museum Quadrat Bottrop © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

The focus on color and form shaped the teaching at the Bauhaus, including that of Josef Albers. After emigrating to the USA, he began his first studies for Homage to the Square in 1950, a series of paintings consisting of three or four nested squares in different colors. In these works, the colors reach into the space as layers of opaque paint, appearing partly translucent and partly overlapping. Albers created over a thousand of these works, which exerted a strong influence on a younger generation of American artists.

We call ‘Concrete Art’ works of art which are created according to a technique and laws which are entirely appropriate to them, without taking external support from experiential nature or from its transformation, that is to say, without the intervention of a process of abstraction. Concrete Art is autonomous in its specificity. It is the expression of the human spirit, destined for the human spirit. ... It is by means of concrete painting and sculpture that those achievements which permit visual perception materialize. The instruments of this realization are color, space, light, movement.

Max Bill: Reflections from dark and light, 1975, Dr. Angela Thomas, Haus Bill, Zumikon, Switzerland. www.maxbill.ch © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025, Photo: Hauser & Wirth

The Swiss designer and architect Max Bill studied at the Bauhaus from 1927 to 1928, where he participated in Kandinsky’s “free painting” class. In retrospect, Bill described Kandinsky as his most important teacher.

Richard Paul Lohse: Thirty Vertical Systematic Color Series in Yellow Rhombic Form, 1943/1970, © Richard Paul Lohse-Stiftung / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

Richard Paul Lohse sought to follow a consistent, transparent logic in his work. His serial process, in which he assigned the same amount of space to each color and made sure no color was repeated in any column or row, was also an attempt to visualize his conception of social equality and exemplify a “radical principle of democracy.”

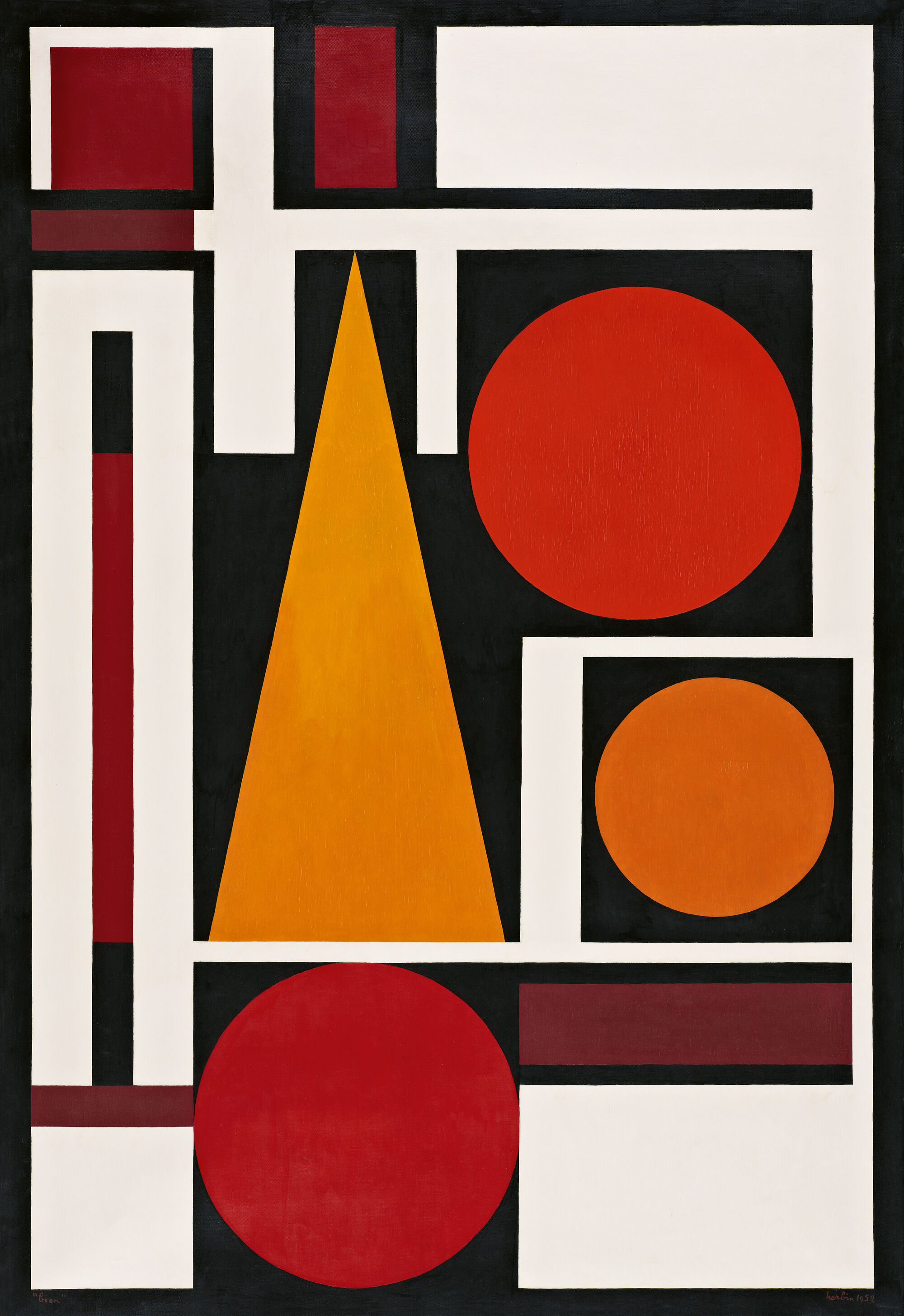

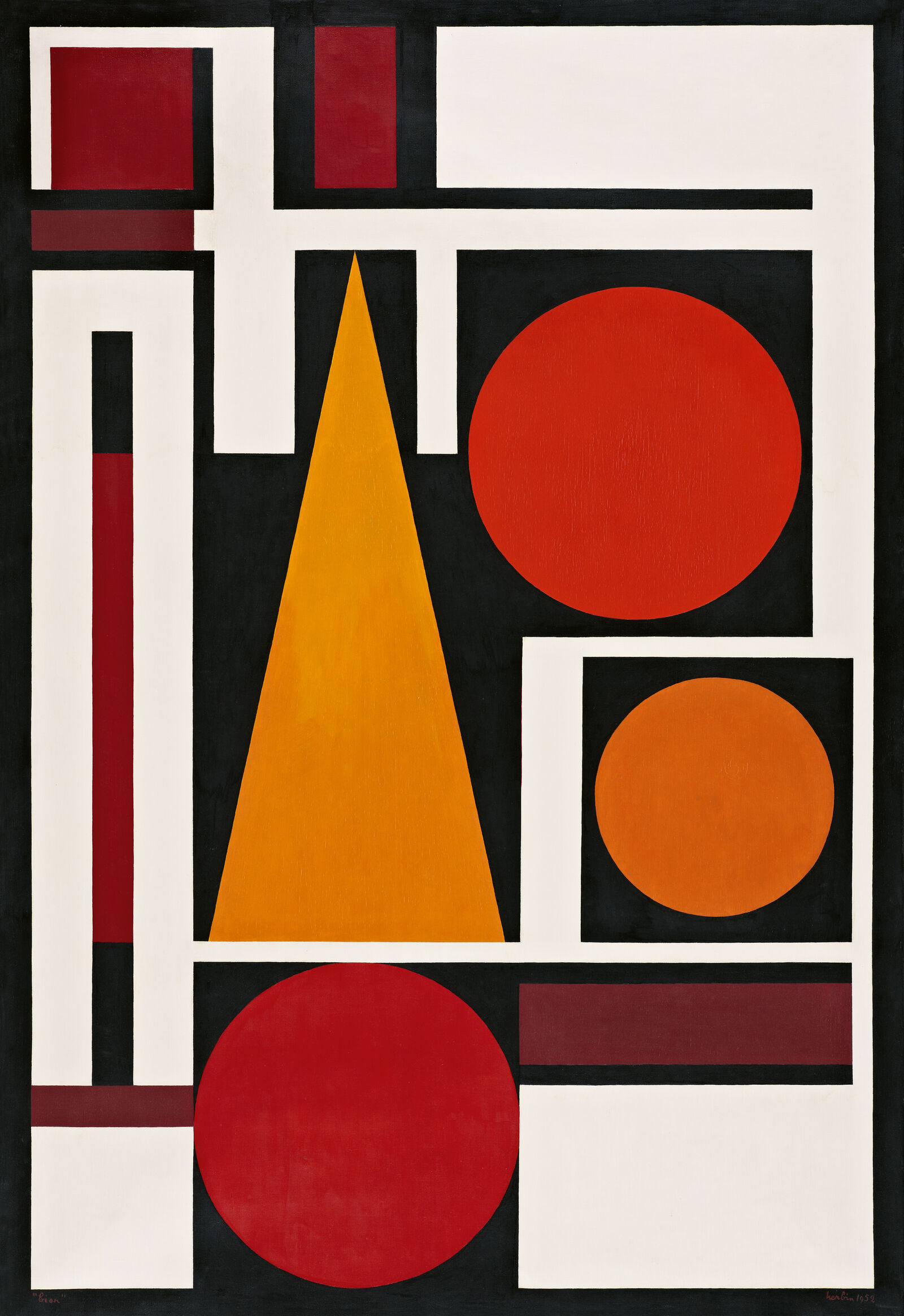

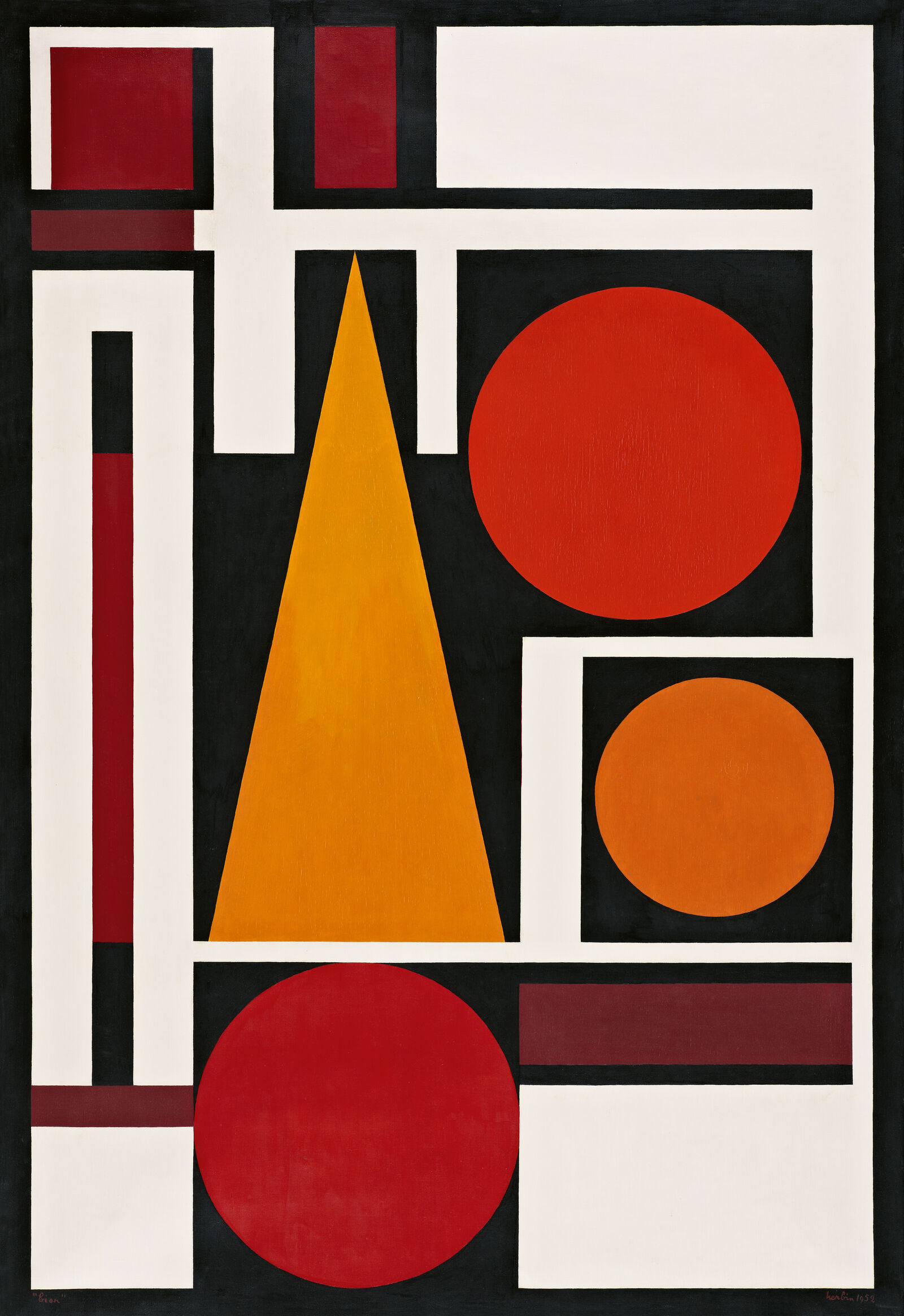

Auguste Herbin: Good, 1952, Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Genève © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025, Photo: Sandra Pointet

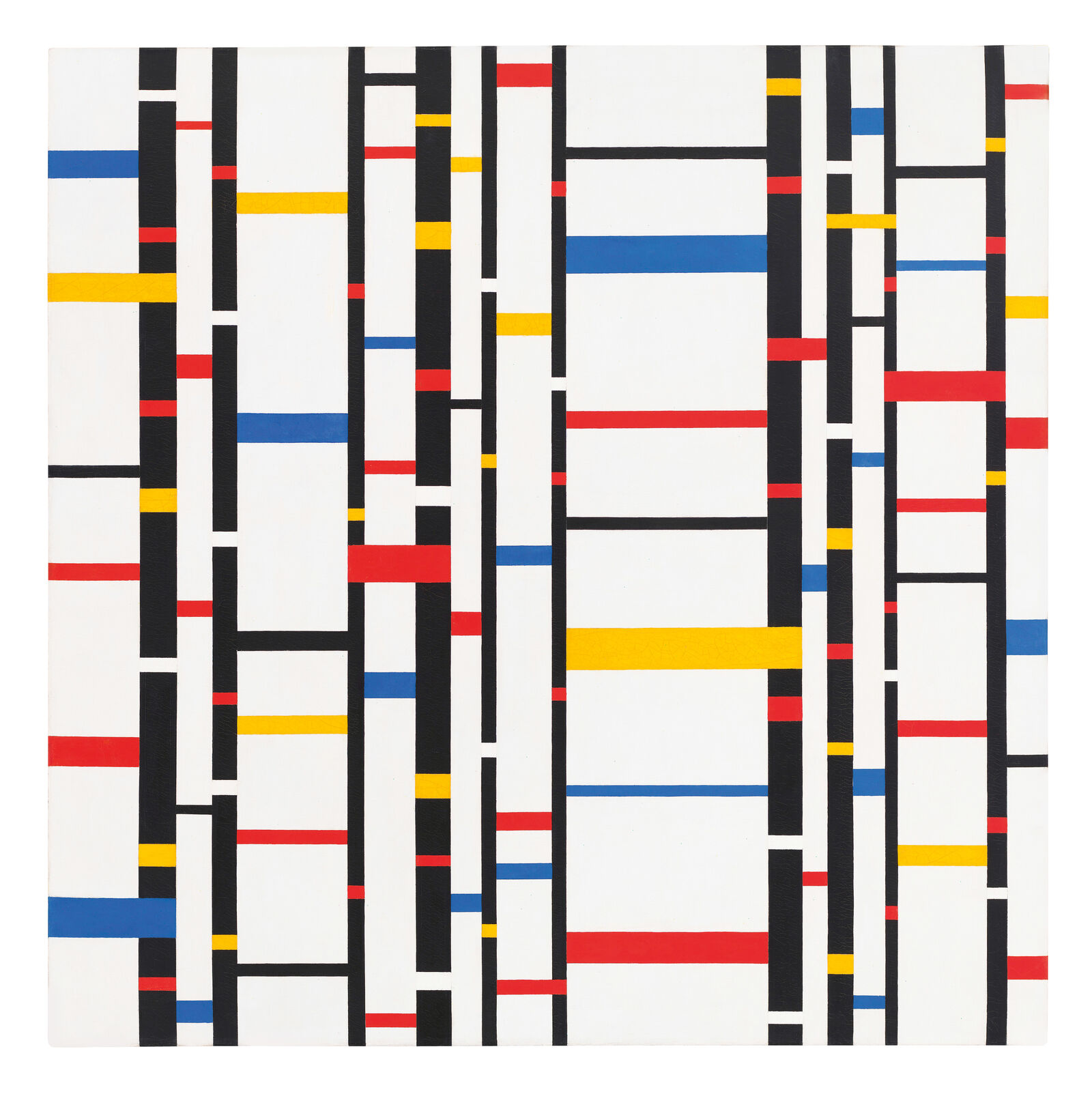

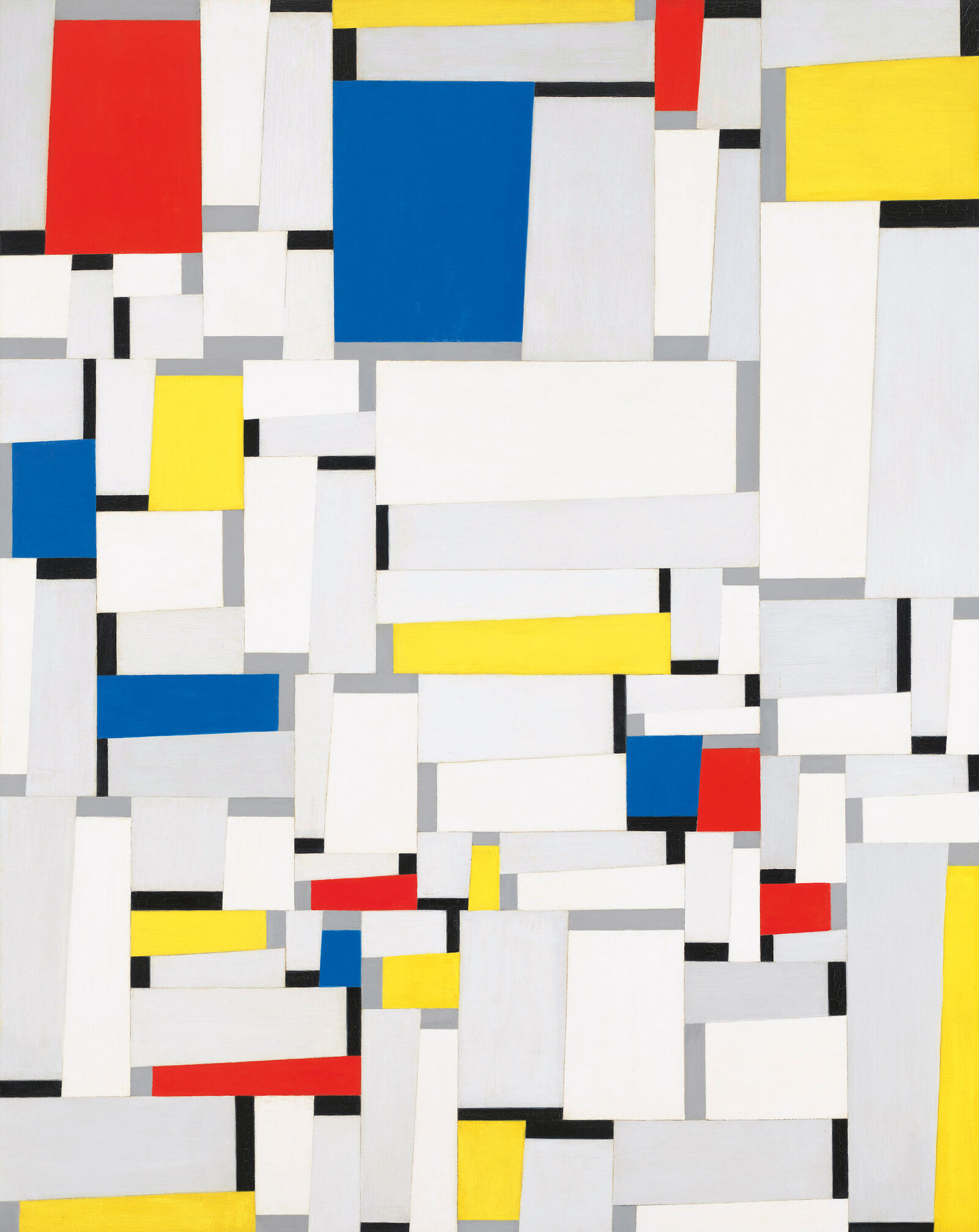

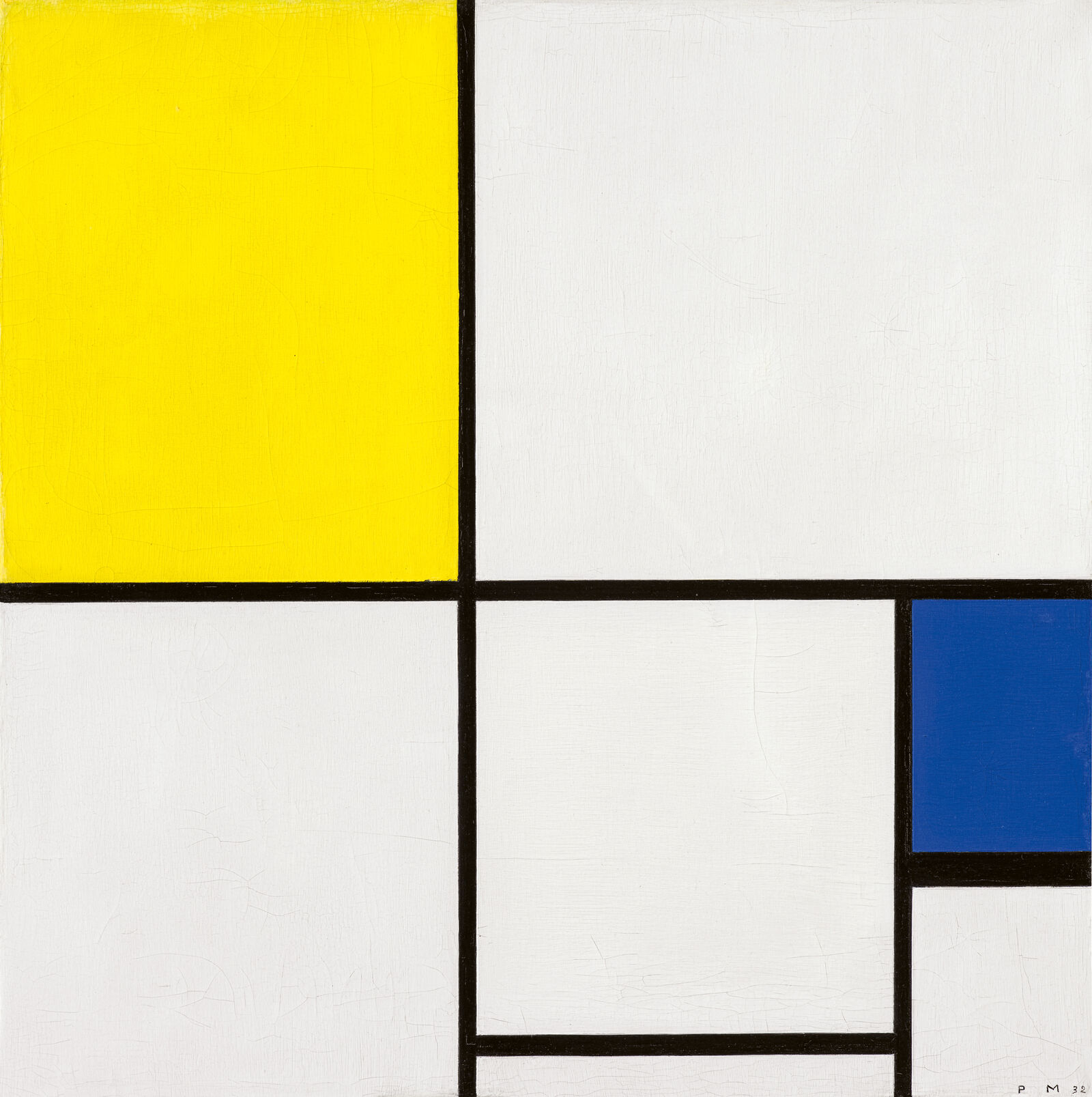

In 1933, Kandinsky emigrated to Neuilly-sur-Seine near Paris. The French capital, still the epicenter of modern art, was a mecca for figures like Piet Mondrian from the Netherlands, who had lived in Paris for extended periods of time since 1912. In 1917, Mondrian had founded the group De Stijl together with Theo van Doesburg, proclaiming a nonobjective art based on horizontal and vertical grids and rectangles in primary colors. This purist style, which was soon adopted by designers as well, resonated with the spirit of the time: Neo-Plasticism, as Mondrian called it, was widely received abroad and was embraced by artists such as Marlow Moss from Great Britain and the Frenchman Jean Gorin.

Piet Mondrian: Composition with Yellow and Blue, 1932, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection, purchased with generous support by Hartmann P. and Cécile Koechlin-Tanner, Riehen

Piet Mondrian intensively studied Goethe’s color theory of 1810. For Goethe, blue and yellow played a special role, representing the fundamental principle of darkness and light.

What do I want to express with my work? Nothing other than what every painter is looking for: to express harmony by the equivalence of the rapports of the lines, the colors, and the overall plan. But to do this in the clearest and strongest way.

César Domela belonged to the second generation of abstract-geometric artists who flocked to Mondrian’s studio in Paris in the 1920s and 30s.

Piet Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism also found adherents in the United States, such as Burgoyne Diller.

The artist Fritz Glarner, who joined the Abstraction-Création group in 1933, likewise pursued an intensive exchange of ideas with Mondrian.

Mondrian had distanced himself from the De Stijl group in the mid-1920s in the wake of discussions on the use of diagonal lines. But his studio in Paris, whose walls, like his paintings, were covered with rectangles in primary colors, still remained a popular destination for young artists. For the American Alexander Calder, the visit to Mondrian was a turning point and prompted him to begin working abstractly himself. Calder designed his first mobiles in the early 1930s.

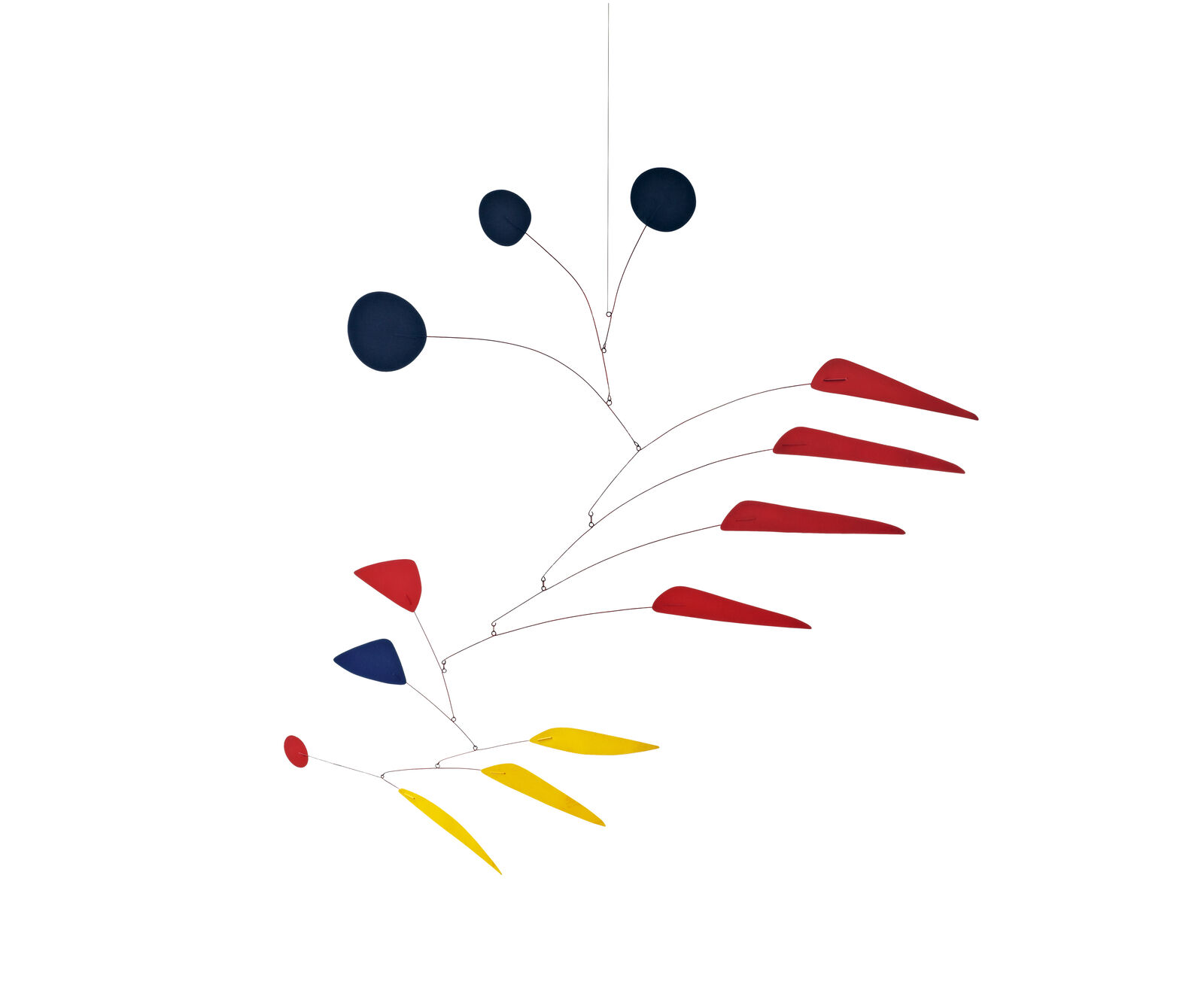

Alexander Calder: Untitled, 1963, Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Genève 2025 © Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Alexander Calder developed his own unique form of abstract art: in his work, geometric and amorphous forms learned to fly.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Twelve Spaces with Planes, Angular Bands, and Laid with Circles, 1939, Kunsthaus Zürich, Geschenk Hans Arp, 1958

Sophie Taeuber-Arp had received training in the applied arts, but crossed the rigid boundary between the fine and applied arts early on. Her abstract painting profited from the decorative patterns of her woven tapestries and the formal repertoire of textile art.

In Paris, the group Abstraction-Création was founded in 1931, uniting a variety of approaches to nonobjective art. Its international members sought to create a platform for abstract art with exhibitions and publications, and in so doing pushed back against the pervasiveness of Surrealism. Yet the boundaries between Surrealist figural fantasies and a purely abstract visual language were permeable: artists like Kandinsky also played with the associative elements of Surrealism.

Wassily Kandinsky: Accompanied Center, 1937, Nahmad Collection

Accompanied Center, a key work from Kandinsky’s Paris years, has a lighthearted quality that flies in the face of the bleak political circumstances of the time.

Constructivist Utopias in British Art

The outbreak of World War II once again altered the map of abstraction. While Kandinsky remained in Paris even after its occupation by the German Wehrmacht in 1940, numerous other modern artists felt the need to emigrate yet again. Some spent time in London, where Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson were experimenting with abstraction in three dimensions. The British Constructivists of the postwar period, also known as Constructionists, discovered the medium of relief as a form of expression. Their reduced abstraction was based on mathematical and therefore universal principles.

Barbara Hepworth: Conoid, Sphere and Hollow III, 1937, UK Government Art Collection © Barbara Hepworth, Bowness

The work of Barbara Hepworth, forged in the heated atmosphere of the 1930s, built a generational bridge to the Constructionists of the 1950s.

I think that so far from being a limited expression, understood by a few, abstract art is a powerful, unlimited and universal language.

Mary Martin: White-Faced Relief, 1959, Sainsbury Centre, University of East Anglia © Paul Martin

Reliefs made from natural or industrially manufactured materials such as Plexiglas or aluminum became a popular field of experimentation for the British Constructivists. Mary Martin also experimented with abstraction in her low reliefs from the early 1950s on.

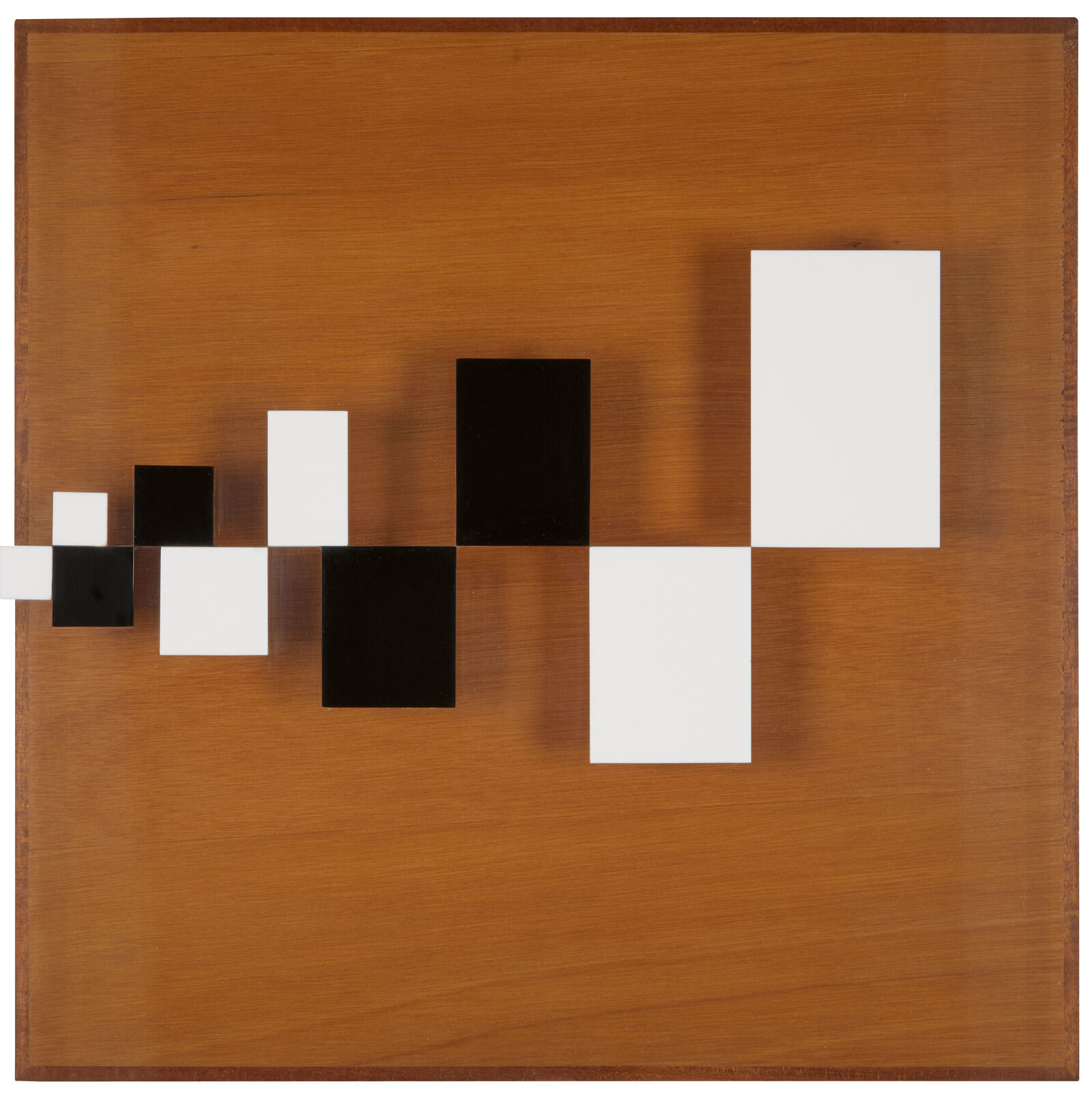

Anthony Hill: Progression of Rectangles, Version II, 1954-1959, Sainsbury Centre, University of East Anglia; Bequeathed by Joyce and Michael Morris, 2014 © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

Most of Anthony Hill’s reliefs are based on mathematical structures. The discipline of mathematics fascinated him throughout his entire life, and in 1979 he became a member of the London Mathematical Society.

Miriam Shapiro: Jigsaw, 1969, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from Mr. and Mrs. Harry Kahn © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025, Photo: 2025 Digital image, Whitney Museum of American Art/Scala, Florence

The postwar years saw the rise of the United States as the driver of the art world. At first the scene was dominated by Abstract Expressionism with its gestural, physical approach to art making, but with the 1960s came a return to clarity of form. In the land of unlimited possibilities, abstract painting, too, was literally freed from all constraints: the scale of the works expanded to monumental proportions, and the centuries-old logic of the rectangular support was abandoned as artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella produced “shaped canvases” with round or polygonal contours. The popular current of Hard Edge painting with its sharp demarcation of forms was characterized by trendy colors and slick surfaces.

Ellsworth Kelly: Blue Yellow, 1968, Private collection © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

With works like Blue Yellow, the American artist Ellsworth Kelly created objects in which color and shape form a unit.

My paintings don’t represent objects. They are objects themselves and fragmented perceptions of things.

Kenneth Noland: Half-Time, 1964, ASOM Collection © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

Like Helen Frankenthaler before him, Kenneth Noland used the “soak-stain” technique, in which heavily thinned paint is allowed to soak into the unprimed canvas.

Al Held: The Dowager Empress, 1965, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025, Photo: 2025 Digital image, Whitney Museum of American Art/Scala, Florence

The tension between two- and three-dimensionality is a central characteristic of the paintings of Al Held.

Paul Reed: Coherence, 1966, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Bill McGillicuddy in memory of Thomas W. Reed and Robert A. Reed

Paul Reed’s work Coherence was inspired by Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles (Number 11) with its repeating rhythm of strong lines.

The flood of manufactured goods in American consumer society also left its mark on artistic production. Instead of oils, many artists used industrial acrylic paints or even wall paint from the home improvement store. The artists of Minimalism suppressed all personal handwriting, creating distance to their works and emphasizing seriality over individual creation. Donald Judd’s blocks of Plexiglas and steel were produced entirely by technicians. His Minimalist objects, consisting of geometric forms, call attention to the space around them.

Donald Judd: Untitled, 1969, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie, Marzona Collection © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

Donald Judd initially studied philosophy and art history. For a long time, he worked as an art critic while pursuing painting on the side. In the 1950s, Judd’s style became increasingly abstract, and in 1962 he began making exclusively three-dimensional works.

Exhibition view Primary Structures. Younger American and British Sculptors, New York 1966, Photo: Rudolph Burckhardt

In 1966, the Jewish Museum in New York mounted a comprehensive exhibition of Minimalist art entitled Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors. The three-dimensional geometric objects were no longer displayed on pedestals, but stood directly on the floor or hung from the ceiling.

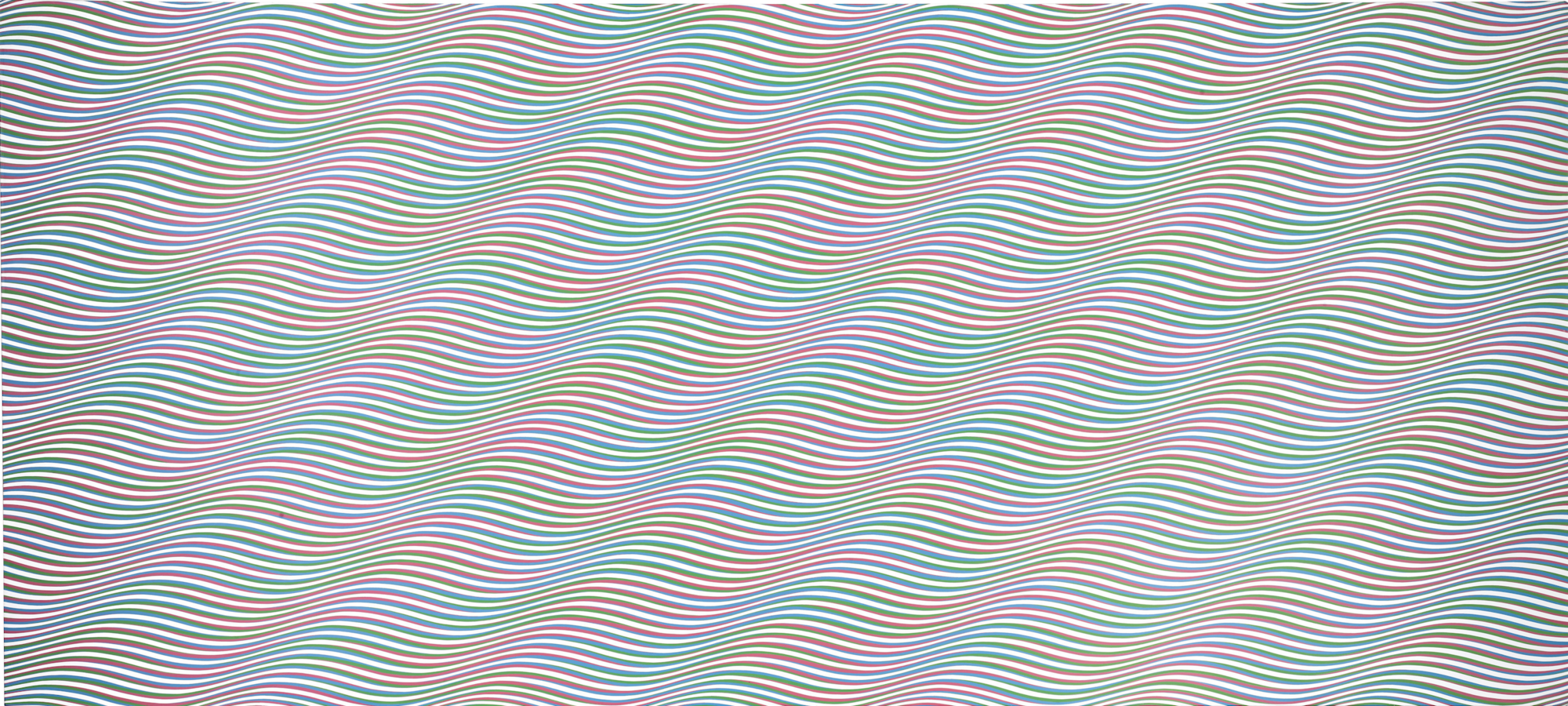

Bridget Riley: Shih-Li, 1975, ASOM Collection © Bridget Riley

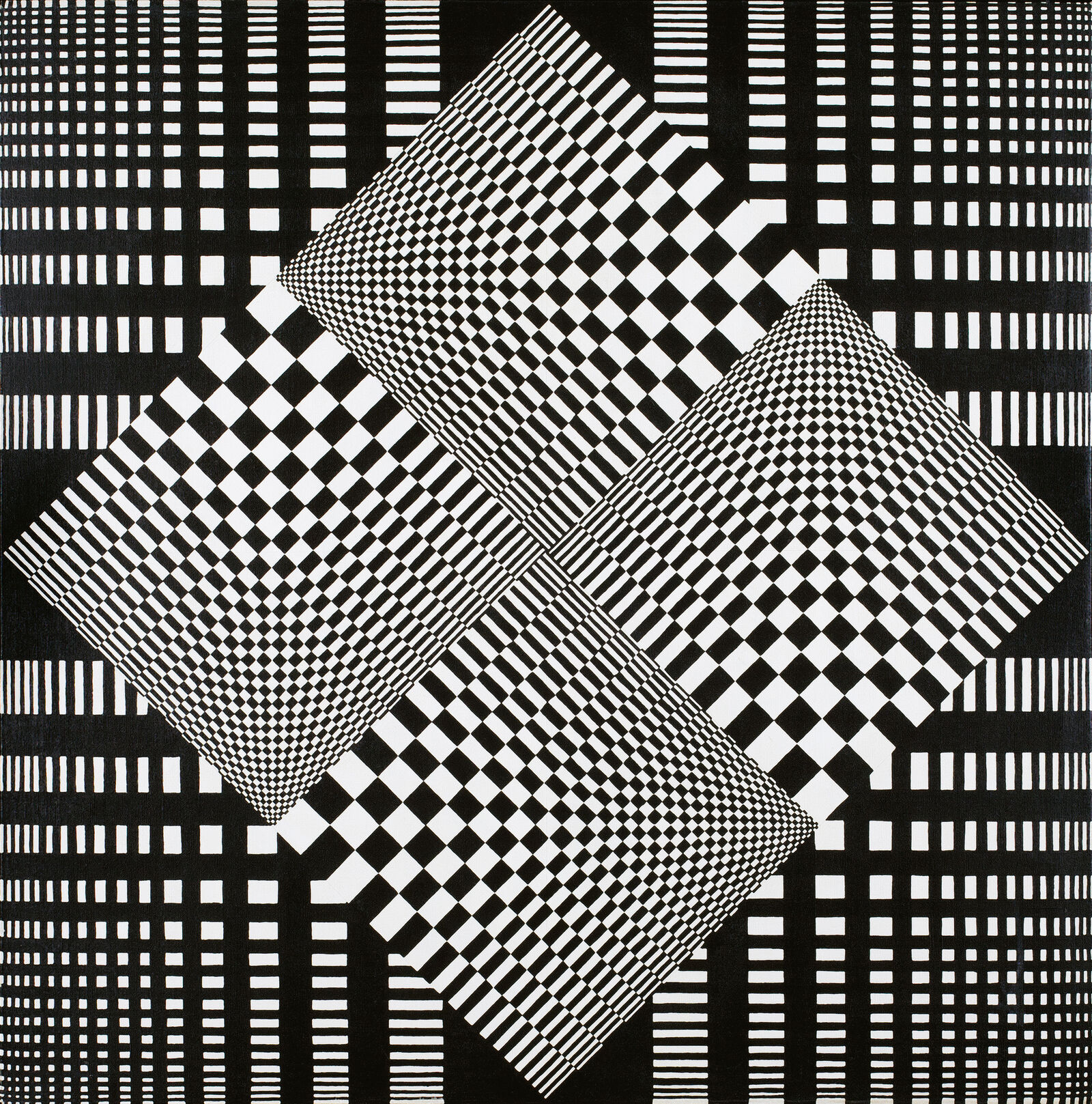

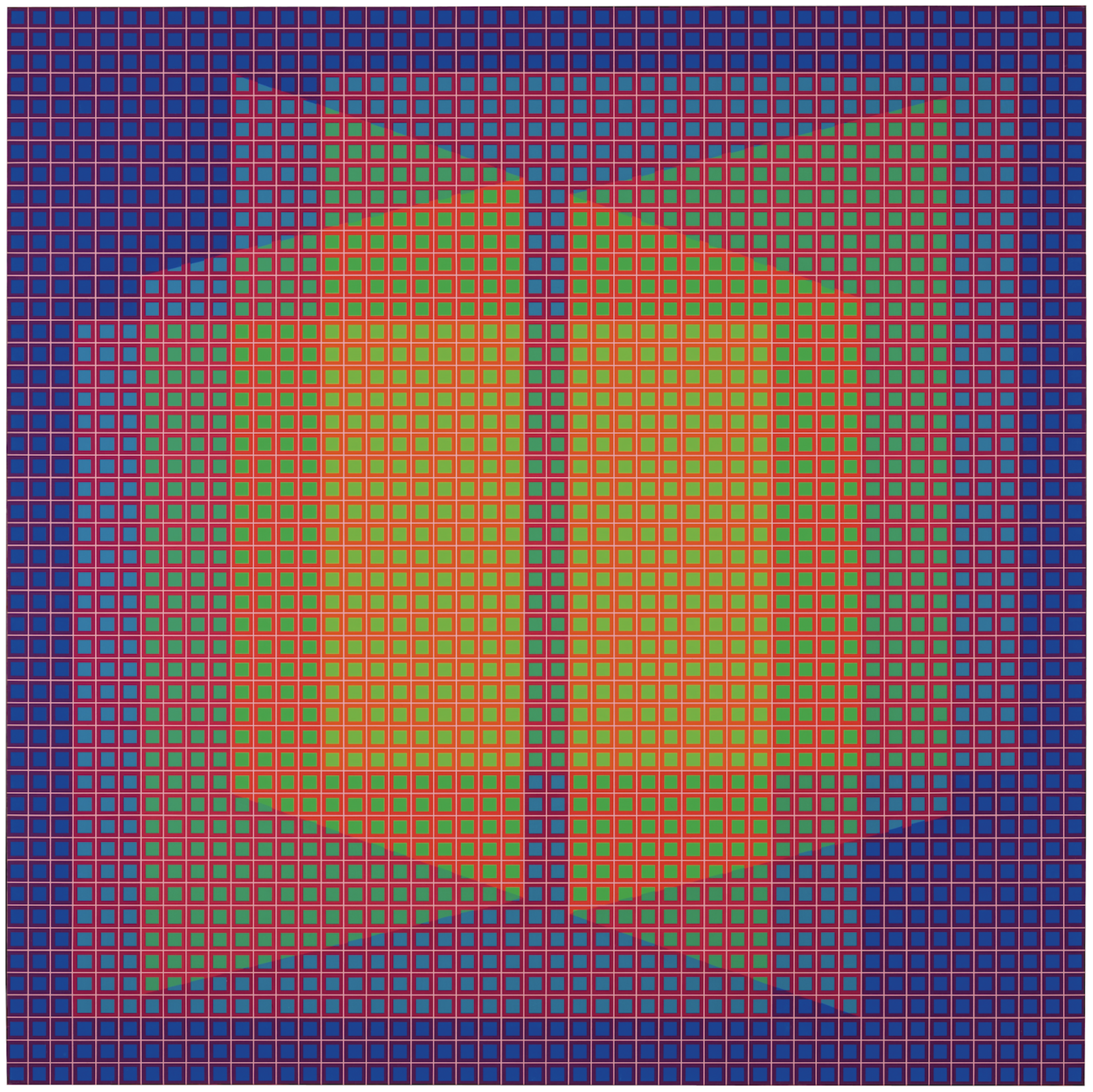

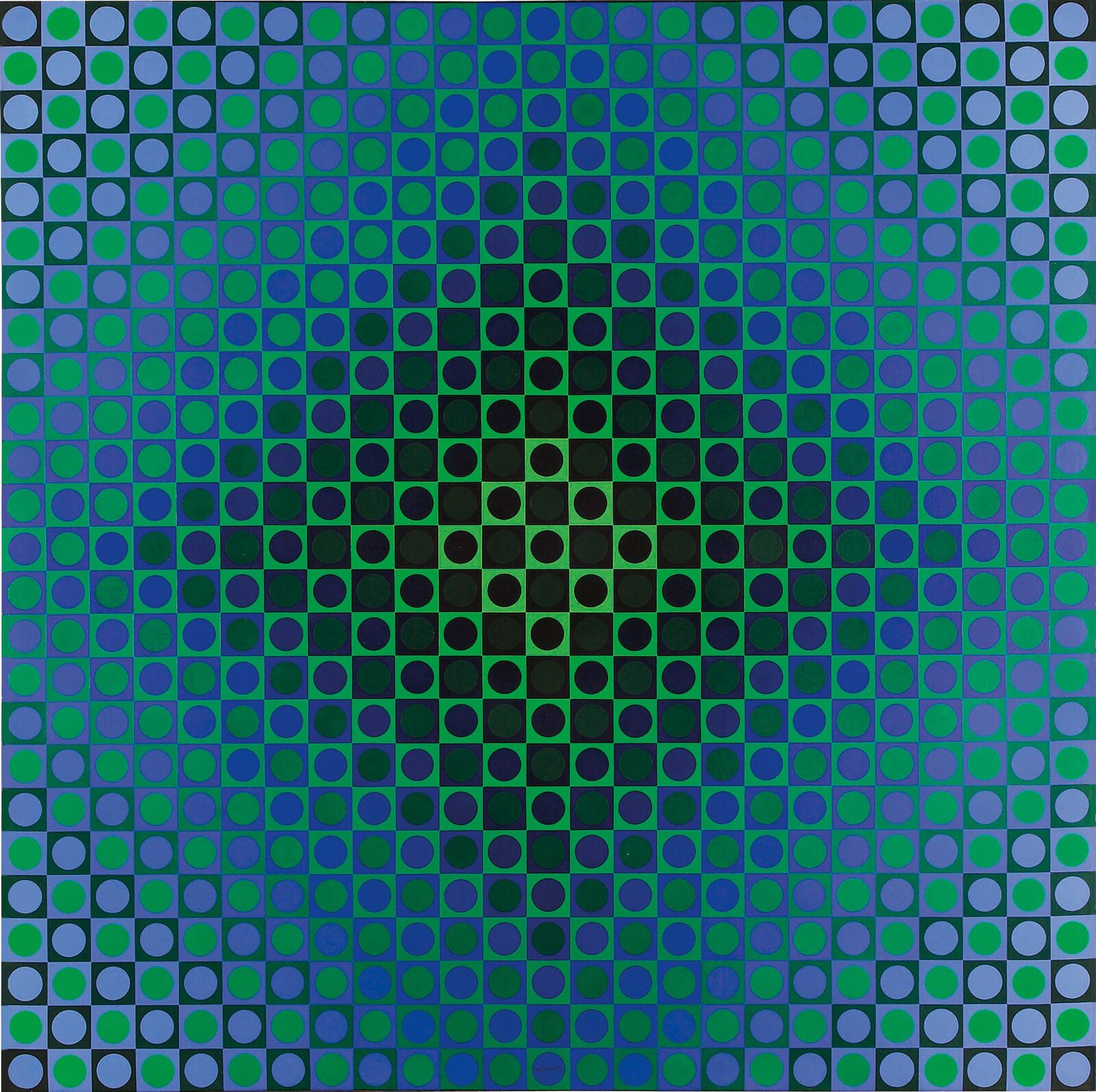

With Op Art (short for Optical Art), geometric abstraction began to dance. The two-dimensional compositions of the British painter Bridget Riley or the American artist Margaret Wenstrup seem to expand, rotate, and vibrate before our very eyes. The influence of psychedelic art and the Space Age is also perceptible: Hungarian artist Victor Vasarely even sent some of his prints into the cosmos on a spaceship.

Margaret Wenstrup: Whirligig , 1964, D. Wigmore Fine Art, Inc., New York © Estate of Margaret Wenstrup, Photo: Noel Allum

Margaret Wenstrup encountered modern currents of abstraction in the New York of the 1940s and 50s. In Op Art, she combined her interests in geometric patterning and textile crafts.

Julian Stanczak: Firefly, 1973, Collection David and Kathryn Birnbaum © Estate of Julian Stanczak, Photo: Wes Magyar

Inspired by his teacher Josef Albers, Julian Stanczak also used the square as a geometric framework.

Op Art explored effects such as distortion or contrast. In so doing, it harkened back to the beginnings of abstract art, when the optical impact of color and form was analyzed by Kandinsky, avant-garde artists in Eastern Europe, and Bauhaus instructors like Josef Albers. At the same time, Op Art—whose name echoes that of the contemporaneous Pop Art movement of the 1960s—rejected spiritual and intellectual interpretations of abstraction and instead focused on the play of perception in the present moment.

Victor Vasarely: Boglar I, 1966, ASOM Collection © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

Victor Vasarely began his career as a commercial artist in Paris in the 1930s. During this time, he also developed an interest in the illusionistic painting known as trompe-l’oeil, aimed at deceiving the viewer’s eye.