The Honest Eye

Born and raised in the Caribbean, Camille Pissarro brought an unusually broad perspective to the circle of Parisian Impressionists and was part of the group from the beginning. With their images of contemporary reality, often painted en plein air, the young Impressionists revolutionized art. Their independent exhibitions caused a sensation and at first provoked vehement criticism. An energetic networker, Pissarro held the loosely affiliated group together and was the only member who participated in all eight Impressionist exhibitions.

Spring at Éragny, 1900, Denver Art Museum, Frederic C. Hamilton Collection, bequeathed to the Denver Art Museum, Photo: William O’Connor, Denver Art Museum

Pissarro discovered nature in all its seasons . . .

Route de Versailles, Louveciennes, Rain Effect, 1891, Clark Art Institute, Williamstow

. . . even in rainy weather.

Pissarro was also politically minded and felt drawn to the utopian ideas of anarchism. As the father of a growing family, he preferred to live in small country towns rather than the metropolis of Paris. He favored everyday motifs, often taken from his rural environment.

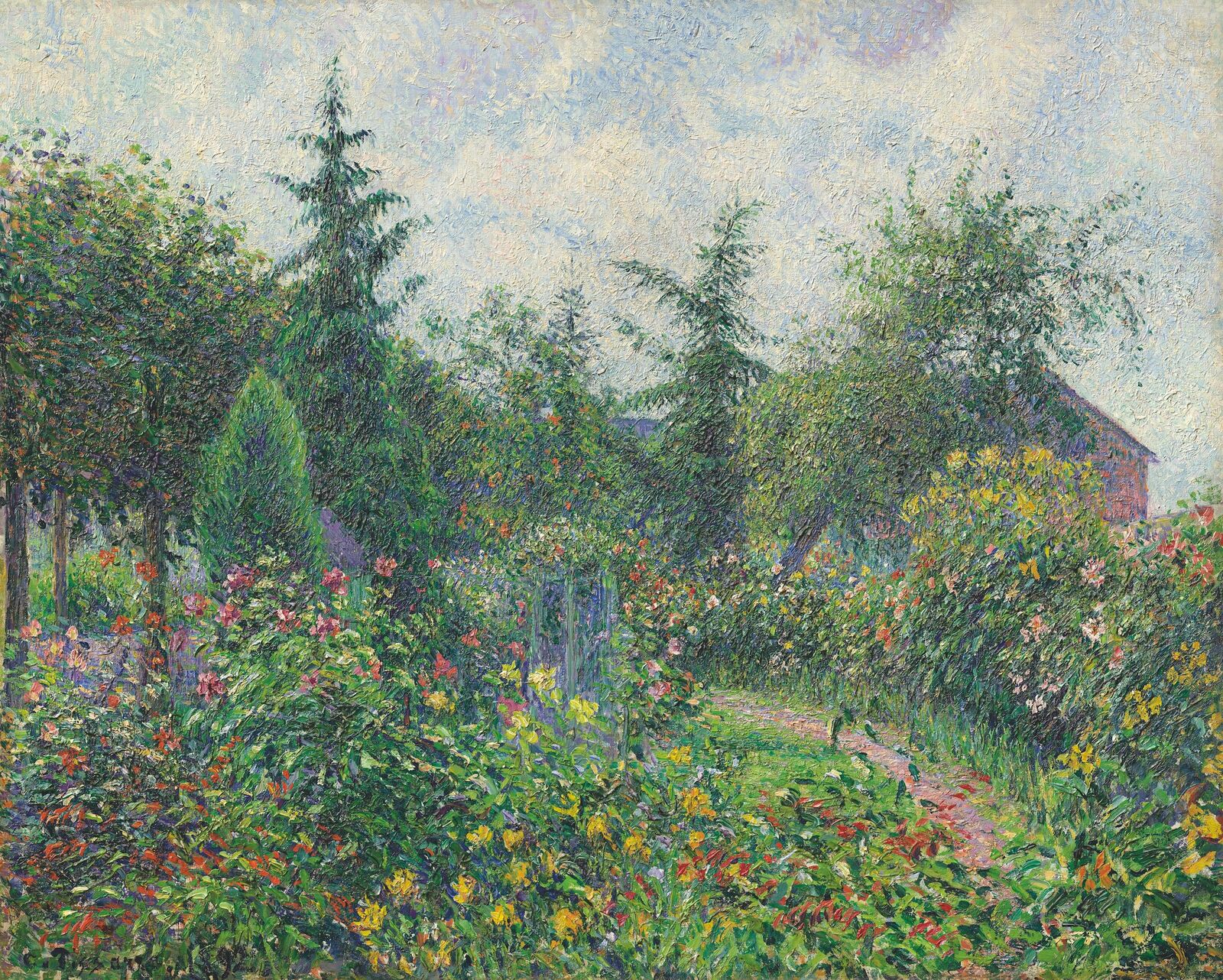

Garden and Henhouse at Octave Mirbeau's, Les Damps, 1892, Hasso Plattner Collection, Museum Barberini, Potsdam

Floral abundance in the garden of the artist’s friend, the anarchist writer Octave Mirbeau.

Pissarro’s pictures often seem unspectacular—but only at first glance! In works of fascinating variety and complexity, he explored rural France, observed the people close to him, portrayed the life of hardworking peasant women, and depicted the dynamic metropolis of Paris. Throughout his entire life, he remained open to new experiences and continued to grow as an artist. Undeterred by financial troubles and sluggish sales, Pissarro stayed true to his own ambitions—and always with a charming hint of self-deprecation.

The Great Bridge in Rouen, Rainy Weather, 1898, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

The painter Pissarro was interested in the sights of the modern world. . .

Pont Boieldieu, Rouen, Effect of Fog, 1898, Colección Pérez Simón, Photo: Arturo Piera

. . . like the steamships, railroads, and factories of Rouen.

Art is indeed the expression of thought, but also of sensation, especially sensation . . .

A Creek in Saint Thomas (Virgin Islands), 1856, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Camille Pissarro’s life began under the palm trees of the Antilles islands. Born in 1830 as a Danish citizen on the Caribbean island of Saint Thomas, then a colony of Denmark, he grew up in a multicultural environment. His parents, prosperous Jewish merchants, wanted him to take over their business—but Pissarro had other plans.

Without further reflection, I left everything behind and fled to Caracas to break the tie that bound me to bourgeois life.

Pissarro and the young Danish artist Fritz Melbye explored Venezuela on their own, not as part of an expedition like previous painters.

Working in the open air, Pissarro honed his skills of observation and his painting technique.

Pissarro spent two years traveling in Venezuela in the company of a young painter friend. During this adventurous trip, he honed his skills in plein air painting and experienced the abolition of slavery. Then he embarked permanently for France, with a firm goal in mind: to become an artist.

It’s almost impossible to keep a young man from going where his passions lead him.

Two Women Chatting by the Sea, Saint Thomas, 1856, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Women on the Caribbean coast.

After arriving in Paris, the young Pissarro continued to paint landscape images of his Caribbean homeland, working from memory or from sketches. The idyllic motifs from distant lands were intended for a European audience. These earliest paintings by Pissarro already bear witness to an interest in simple people and a special sensitivity to atmospheric landscapes.

Pontoise, 1867, National Gallery Prague

Cabbage fields and farmland under brilliant blue or overcast skies—and everywhere fresh, open air: Pissarro’s early paintings from his Paris years show a new interest in the direct experience of the everyday environment. Critics were disconcerted and found the motifs ugly. In the open drawing studio of the private Académie Suisse, Pissarro made new friends and met like-minded artists. One of them was Claude Monet. They painted together, preferably outdoors like the artists of the Barbizon School before them.

The Banks of the Marne in Winter, 1866, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection, 1957.306, bpk / The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

This bleak and melancholic painting established Pissarro’s reputation as a modern landscape painter.

In that day, the most important public platform for artists was the annual Salon de Paris, a major exhibition where thousands of paintings competed for acceptance and prizes. The academy’s jury is considered conservative—but Pissarro was admitted to the show and quickly gained a reputation as a proponent of modern landscape painting.

M. Pissarro is an unknown and probably no one will talk about him. . . . Thank you, Monsieur, your winter landscape refreshed me for a good half hour, during my trip through the great desert of the Salon. . . . Besides which, you ought to know that you please nobody and that your painting is thought to be too bare, too black. So why the devil do you have the arrant awkwardness to paint solidly and study nature so honestly!

The banks of the Oise River in Pontoise show signs of industrial activity.

A brighter palette already points toward Impressionism.

While living in the towns of Pontoise, and Louveciennes near Paris, Pissarro explored the region along the Seine. Factory smokestacks often appear in the background of his images. The artist did not shy away from industrialization, but showed it as a contemporary phenomenon.

Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich, 1871, The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)

In this first Impressionist painting of a railroad, Pissarro shows a train leaving the suburban station of Dulwich near London.

With the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Pissarro and his family fled to London. There he met his later Paris art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel and once again encountered his friend Claude Monet. In the National Gallery, he studied the paintings of John Constable and William Turner, works that encouraged him to pursue a realistic, atmospheric approach to the landscape using brilliant hues and loose brushwork.

The Highway (La Côte du Valhermeil, Auvers-sur-Oise), 1880, The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland

On April 15, 1874, the day had come: the first exhibition of the “Societé anonyme coopérative des artistes peintres etc.” opened at the studio of the photographer Nadar in Paris. The group of young artists would soon become known simply as the “Impressionists,” a term originally coined by a contemptuous critic. But the sense of immediacy, the capturing of the momentary, fleeting, and atmospheric became the trademark of the new movement. Seven more exhibitions would follow from then until 1884, independently organized and with a changing roster of artists. Pissarro remained a driving force and was the only member of the group who never again submitted work to the official Salon. The rigid, academic style of the Salon was too stark a contrast to the artist’s commitment to independence and freedom.

Hoarfrost, 1873, Paris, musée d'Orsay ; Legs Enriqueta Alsop au nom du Dr Eduardo Mollard, 1972, Photo: akg-images / De Agostini Picture Lib. / G. Dagli Orti

At the first Impressionist exhibition, Pissarro showed this painting of a frosty winter day in the country.

Those furrows? That frost? But they are palette-scrapings placed uniformly on a dirty canvas. . . .—Perhaps . . . but the impression is there.—Well, it’s a funny impression!

The works of the Impressionists provoked vehement reactions, most of them negative. Many critics viewed the paintings as too unfinished, too sketch-like and ephemeral. Prevailing academic conceptions of art called for a high level of technical skill and refinement in painting, and biblical or mythological scenes enjoyed the most prestige. But the Impressionists wanted to depict contemporary life, trusting their own perception. They studied changing weather phenomena and the effects of light with keen observation and the highest concentration.

Our exhibition is going well, it’s a success. The critics are tearing us apart. . . . I’m going back to my studies, it’s better than reading the reviews; there’s nothing to be learned from them.

The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri (Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust). 60–38, Image courtesy of Nelson-Atkins Digital Production & Preservation, Joshua Ferdinand

Dieses Anwesen bewohnt die bekannte Frauenrechtlerin Maria Deraismes. Pissarro teilt ihre fortschrittlichen Ansichten.

Pissarro was represented with numerous works at all eight Impressionist exhibitions. His paintings, unlike those of his friends Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, almost never showed the lifestyle and leisure of the well-heeled upper class. He was interested in the simple folk, the hardworking rural population—but such motifs were not popular among buyers, and Pissarro had a hard time making sales.

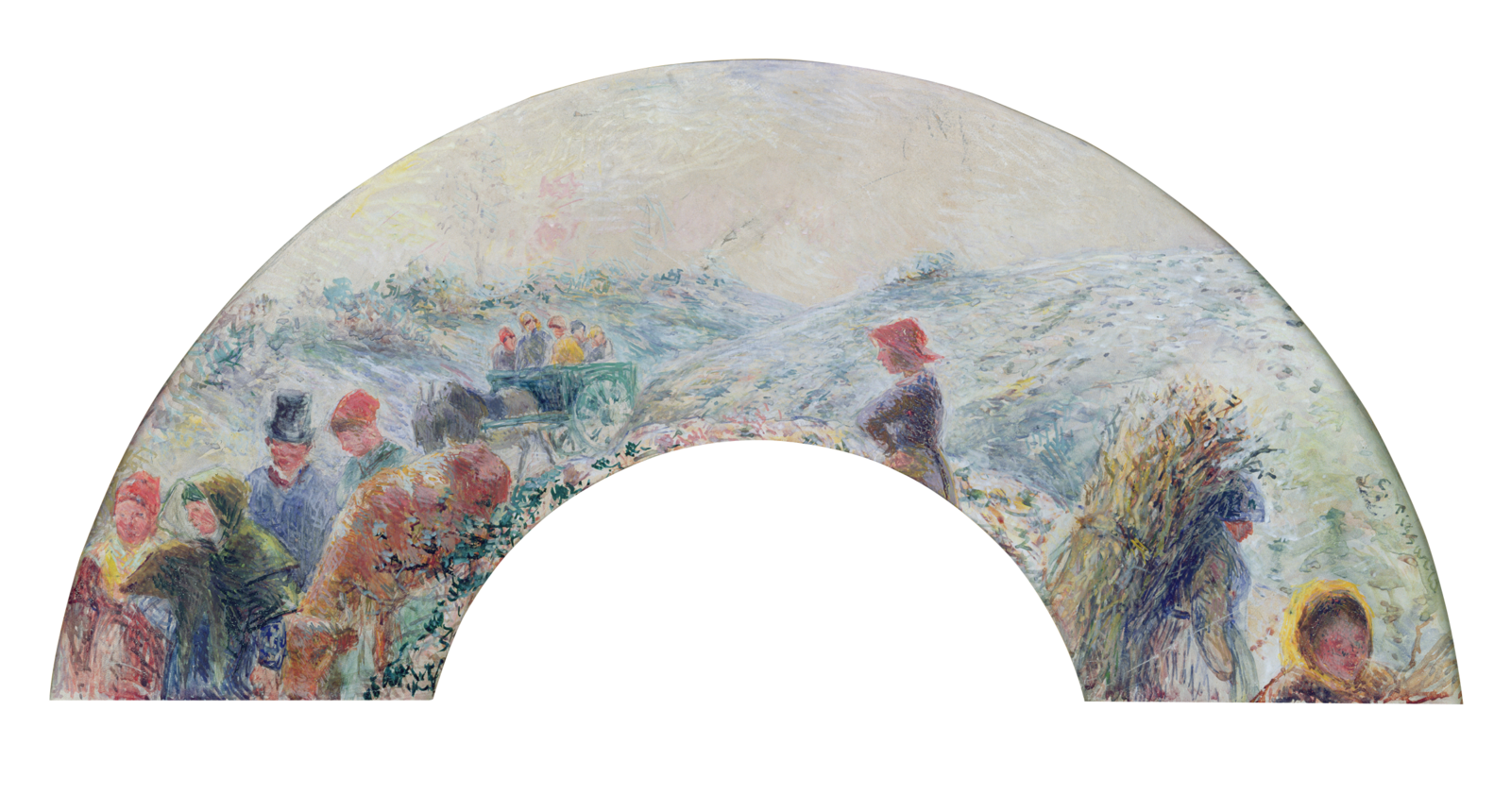

Pissarro’s winter scene Return from the Fair was shown at the fourth Impressionist exhibition in 1879.

The brightly colored image of the harvest was acquired by the artist’s friend, the Impressionist Berthe Morisot.

Avant-garde decoration: Pissarro’s painted fans were shown at multiple Impressionist exhibitions. At that time, fans were all the rage in Paris. Inspired by Japanese craftsmanship, they flooded the market not only as elegant ladies’ accessories, but also as wall decoration. The unusual format appealed to the experimentally-minded Pissarro, who also hoped for a new source of income and a broader base of buyers to remedy his ongoing financial straits.

I don’t think he has much say in the household, where his wife wears the pants.

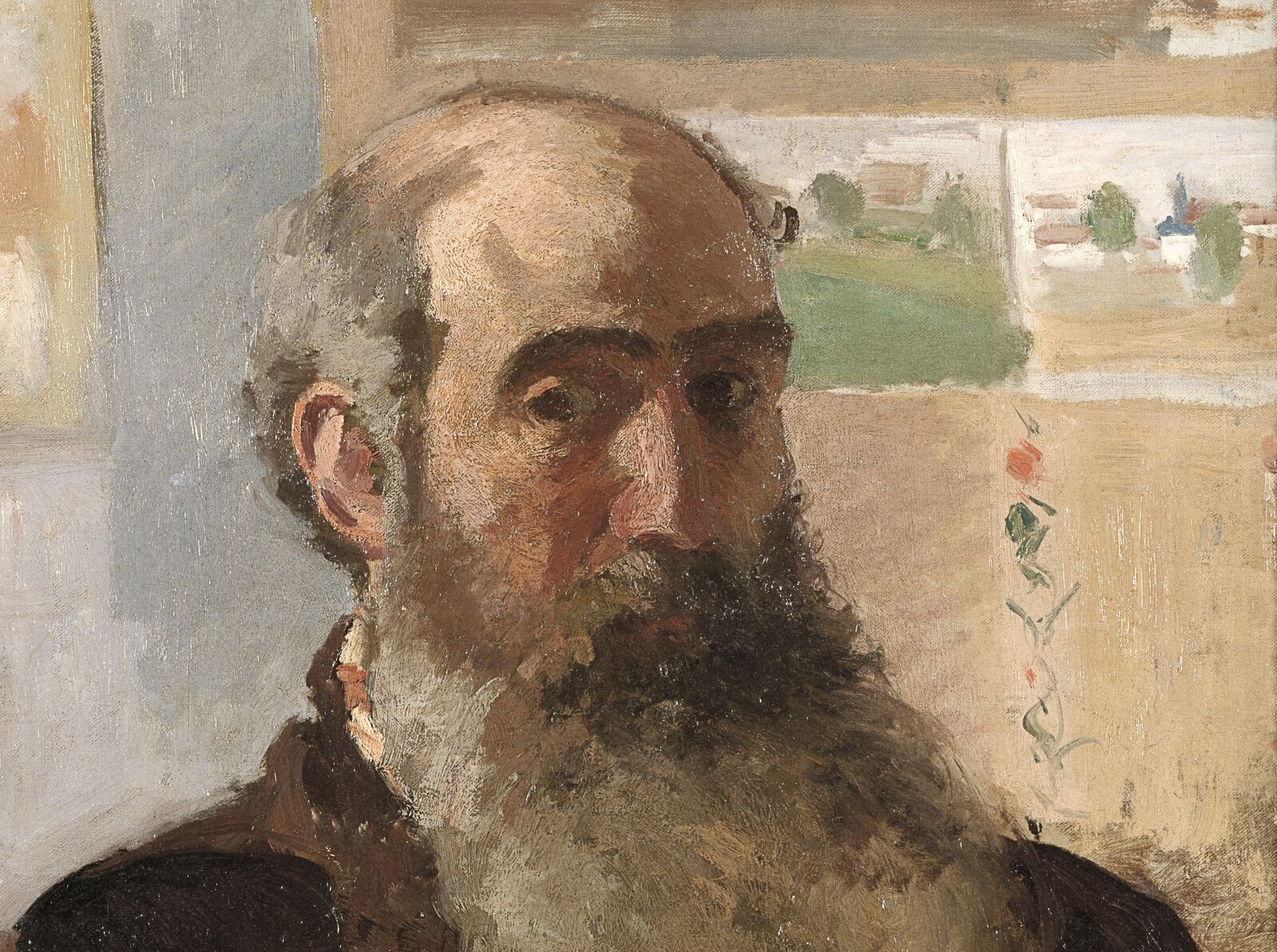

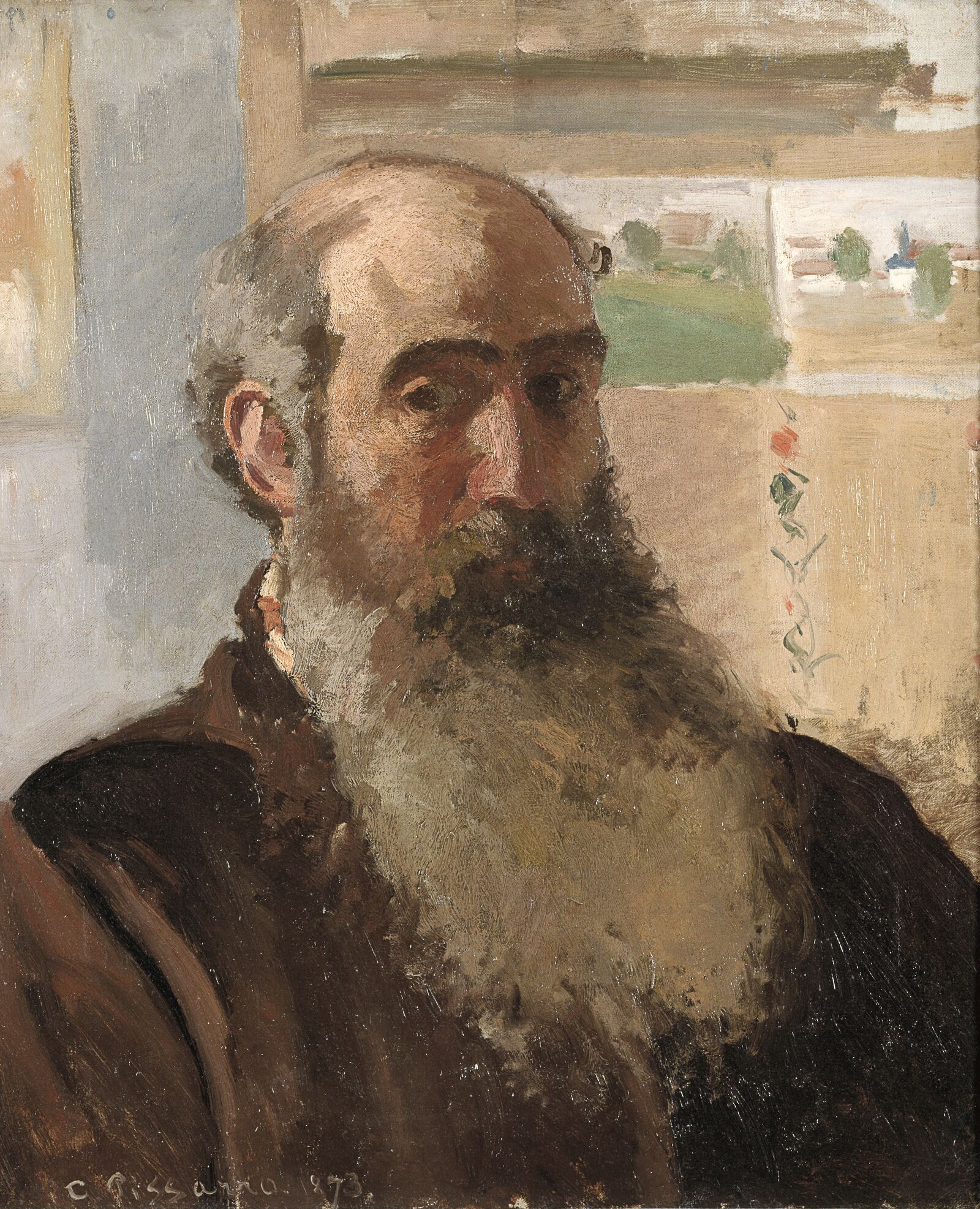

Portrait of the Artist, 1873, Musée d'Orsay, Paris, Donation Paul-Emile Pissarro, 1930, © akg-images / Laurent Lecat

Pissarro seldom painted himself.

Julie Pissarro Sewing Beside a Window, 1877, The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Presented by Esther Pissarro, 1951

The artist shows his wife Julie working on her sewing.

Pissarro’s family was tremendously important to him. When he and his wife Julie meet, she is working as a kitchen maid for his parents. The daughter of a winegrower’s family in Burgundy, Julie Vellay came from simple circumstances. Eight children are born from their marriage that lasts a lifetime. However Pissarro’s unstable income was often a source of conflict. Julie contributed to the support of the large family through thrifty household management and the cultivation of her own vegetable garden.

Portrait of Jeanne Pissarro, 1872, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, John Hay Whitney, B.A. 1926, M.A. (Hon.) 1956, Collection

The painter sensitively portrays his little daughter Jeanne, known as Minette, wearing a pink dress . . .

Jeanne Pissarro (Minette) Holding a Fan, 1873, The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Bequeathed by Esther Pissarro, 1952

. . . and again four years later, weakened by illness. Minette died at the age of only nine.

Pissarro lovingly participated in the rearing of his children. As a devoted father with liberal educational ideals, he did everything in his power to encourage their creativity. All five of his sons embraced artistic professions—whether in printmaking or the field of the applied arts—despite his wife Julie’s concern over the difficulty of earning a living as an artist.

Die Heumacherin, 1884, Colección Pérez Simón

Arturo Piera

Human figures played an increasingly important role in Pissarro’s landscapes. He showed the peasants at work, portraying them with dignity and respect. Integrated into the rhythm and cycle of the seasons, they turn hay, harvest, plant, and sow, just as in centuries gone by, seemingly far removed from the hustle and bustle of the big city. Such images also convey the vision of a social utopia, the dream of a self-determined life and communal work in harmony with nature.

The Pork Butcher, 1883, Tate, Bequeathed by Lucien Pissarro, the artist's son 1944

Women at work: a young butcher woman in a white apron arranges her market stall.

Whether selling at the markets or laboring in the field, the figures Pissarro portrayed were most often women. They perform their daily tasks with ease; they seem content, energetic, skilled, and lively. In such works, the painter shaped an entirely new image of womanhood, free of erotic undertones and the traditional gender stereotypes of art history.

Pissarro made multiple figure studies to develop his motifs.

In chalk pastels and watercolor, the artist captured peasant women making hay, embedded in greenery.

Warm colors convey a peaceful, harmonious mood.

Pissarro’s images of rural life show no evidence of plague, toil, or exhaustion; it seems there is always time for a break or to engage in conversation while working. The rhythmic movements of the figures, primarily women, resemble a round dance and are carefully choreographed. The painter meticulously developed his elaborate multifigure compositions through numerous sketches and studies.

For a long time now, Mr. Pissarro had ceased to work exclusively in front of nature, to render its momentary . . . details. After having fixed in watercolor or pastel the physiognomy of a site, the appearance of a farmer . . . , he devotes himself, far from the motif, to a work of composition . . . : only the essential aspects . . . remain.

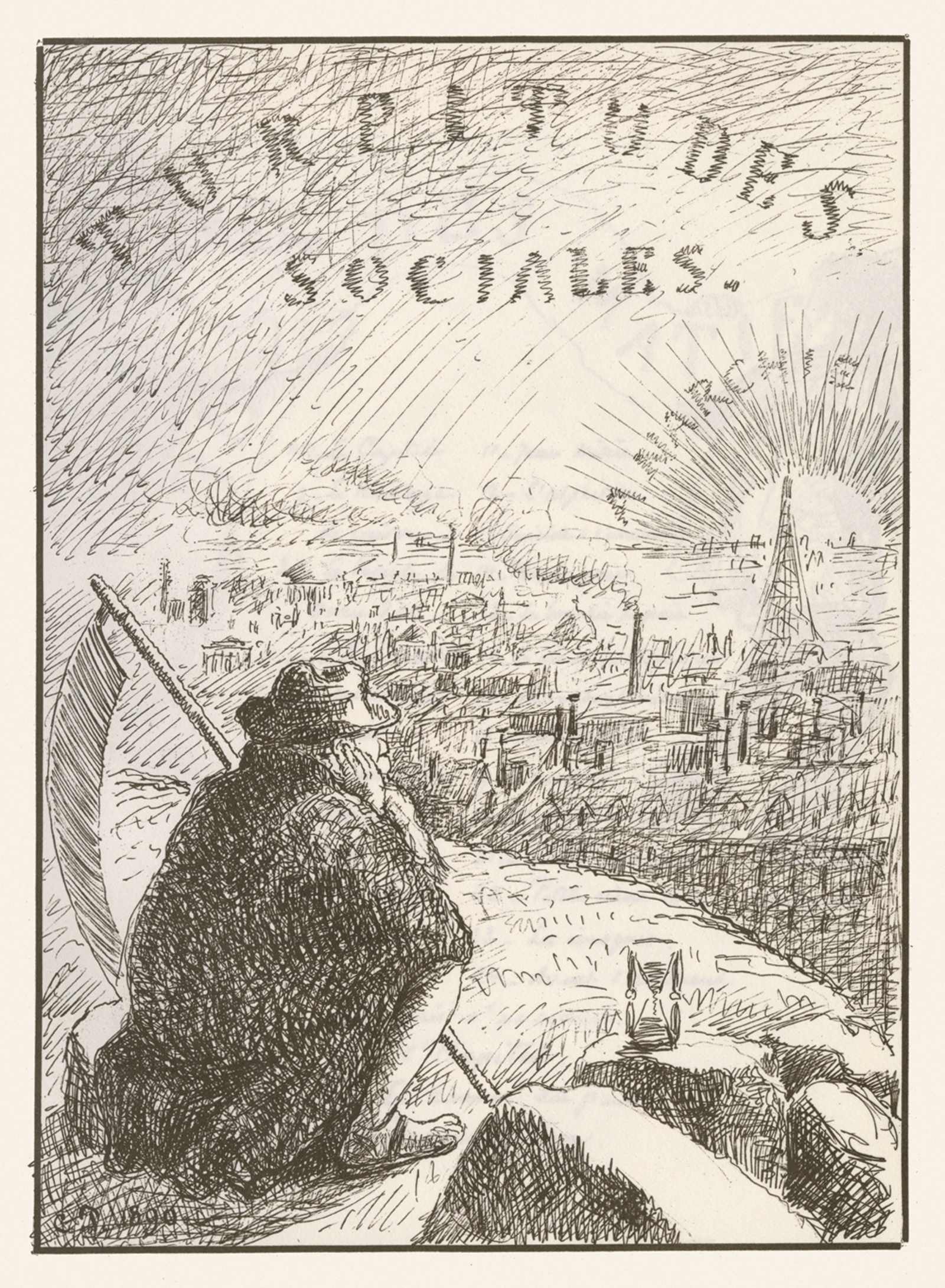

The artist was deeply interested in the social ideas of anarchistic writers and thinkers. He read the works of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin and discussed them with his children and friends. Pissarro subscribed to anarchist magazines, and sometimes even provided illustrations for them. The anarchists rejected all forms of government. For them, the free self-organization of people in society was the path to a better life for all, with the independent labor of self-sufficient farmers playing a central role.

All the arts are anarchistic when they are beautiful and good!

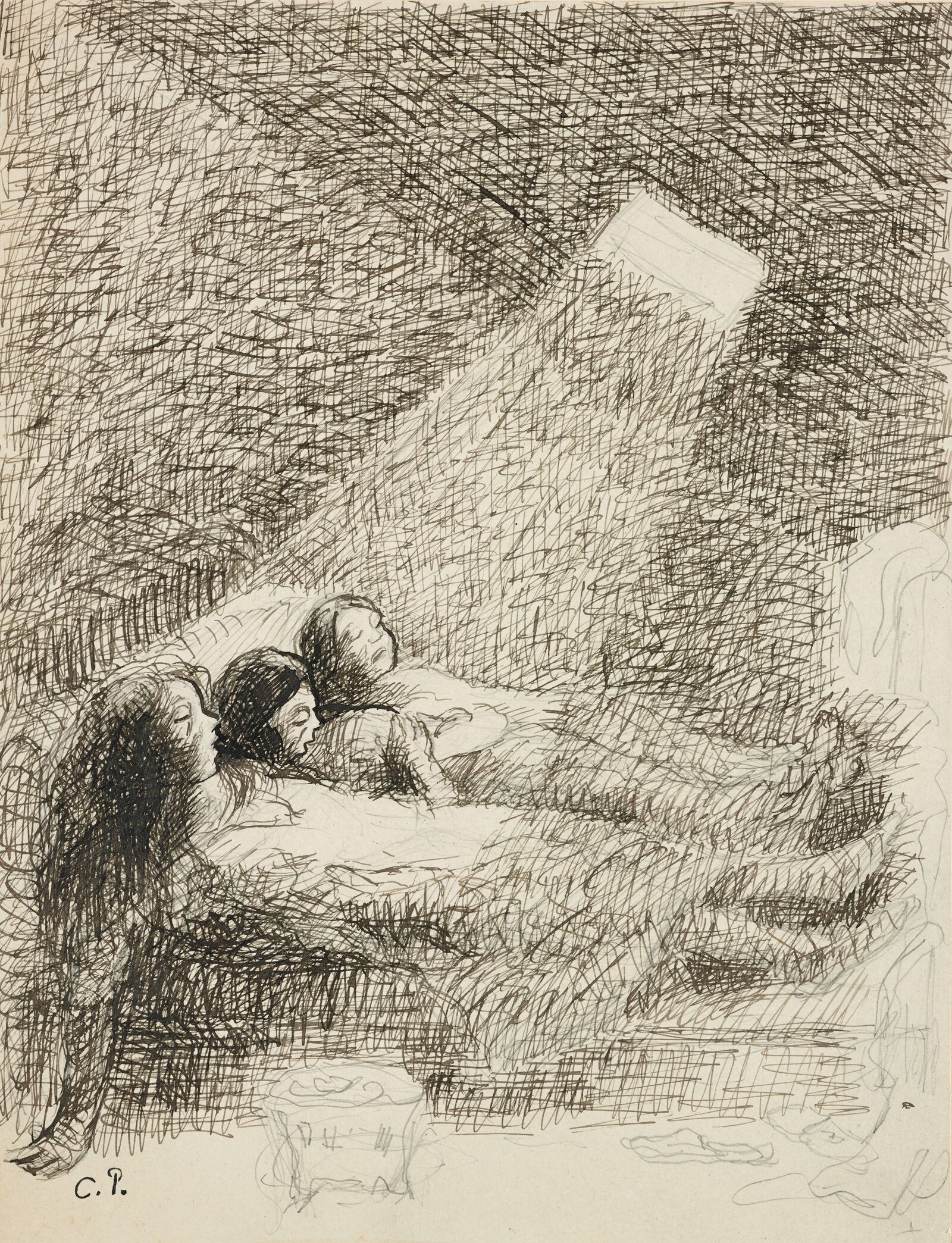

Pissarro voiced his political convictions only subliminally in his paintings. He expressed himself more pointedly in the album Turpitudes Sociales (Social Disgraces), where he used ink drawings to sharply criticize the ills of society. He sent these caricature-like images to his nieces in England to instruct them in the failings of government and politics.

The word “Anarchy” shines hopefully above the Eiffel Tower on the title page of Turpitudes sociales (Social Disgraces).

Pissarro lampoons corrupt, greedy bankers.

Unbearable working conditions: The stove in the foreground suggests that the mother took her own life along with her children.

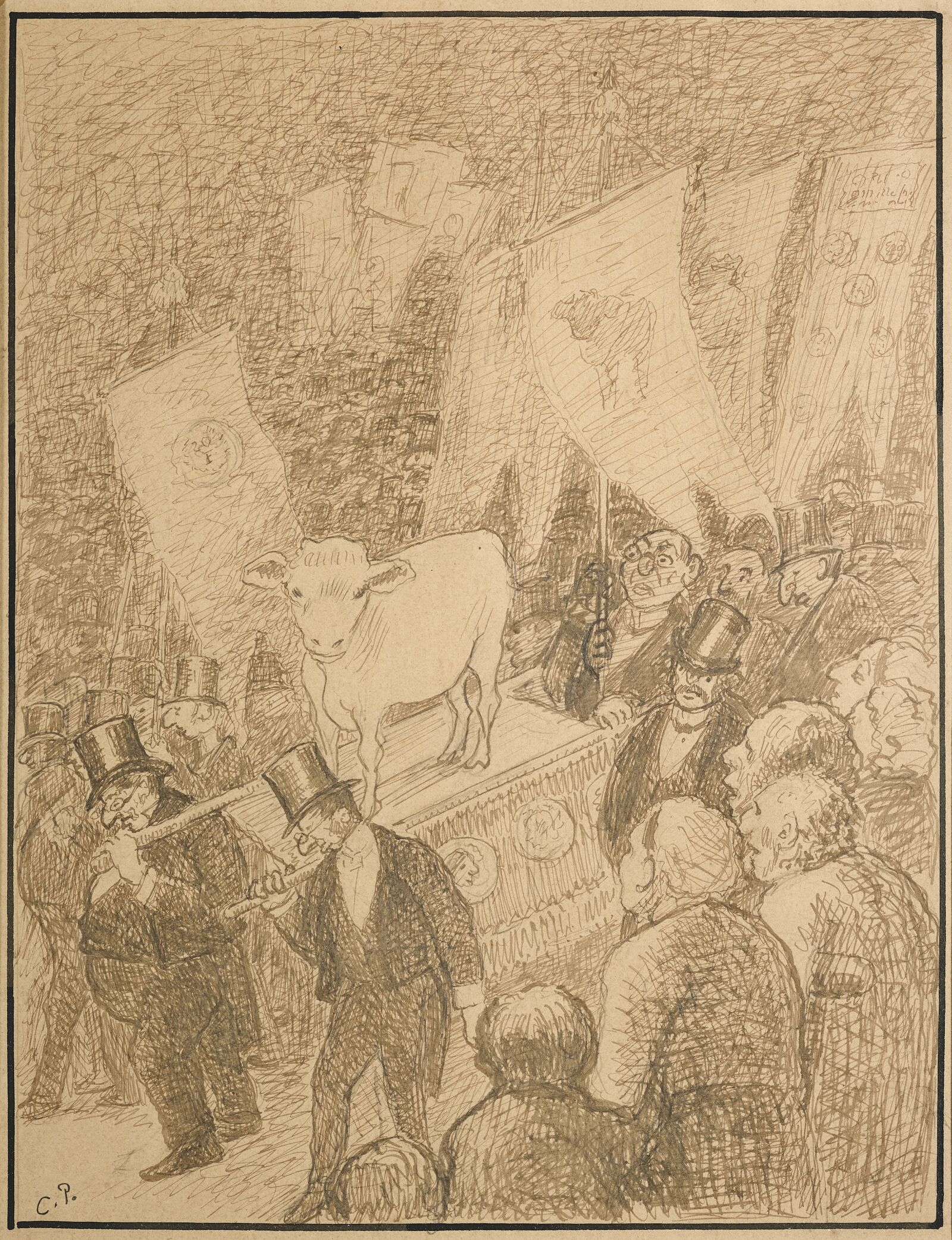

The idolatry of capitalism: in a reference to the biblical story, corpulent men in suits venerate the Golden Calf.

My dear niece, I understand perfectly that you may not be familiar with political matters. . . . However, you should know that universal suffrage [is] the instrument of domination for the capitalist bourgeoisie. . . . So—no government, no state, no capitalists. . . . I refer you to Kropotkin’s truly remarkable book, written in a very simple style, easy to read, and as clear as crystal!

Shepherd and Sheep, 1890, Colección Pérez Simón, Photo: Arturo Piera

Pissarro’s political convictions and his hope for harmony between man and nature shine through in many of his works.

I have just read Kropotkin’s book. It must be admitted that if it’s utopian, in any case it’s a beautiful dream. And because we have often had examples of utopias become realities, nothing prevents us from believing that it will be possible one day, unless man sombers and returns to complete barbarity.

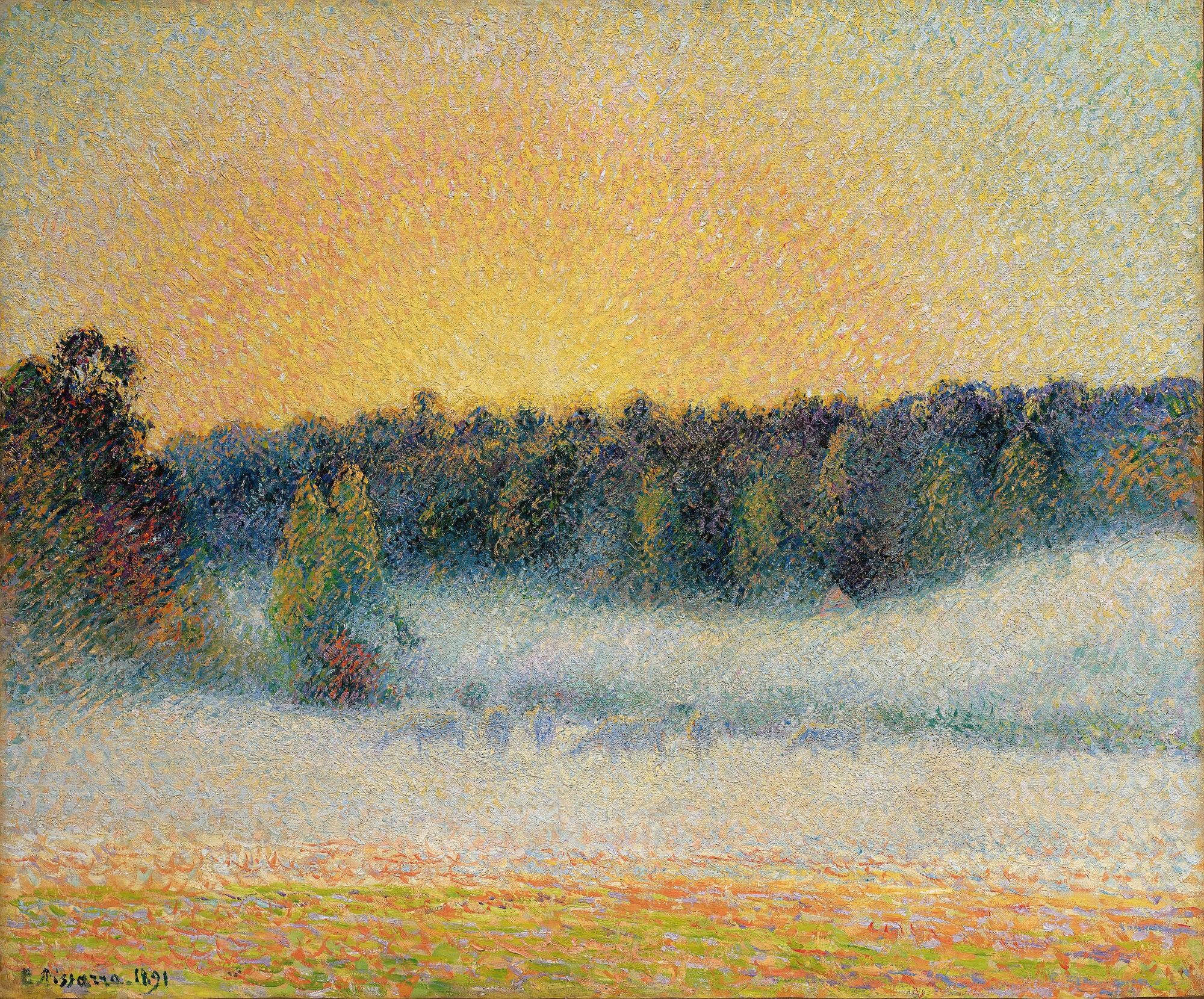

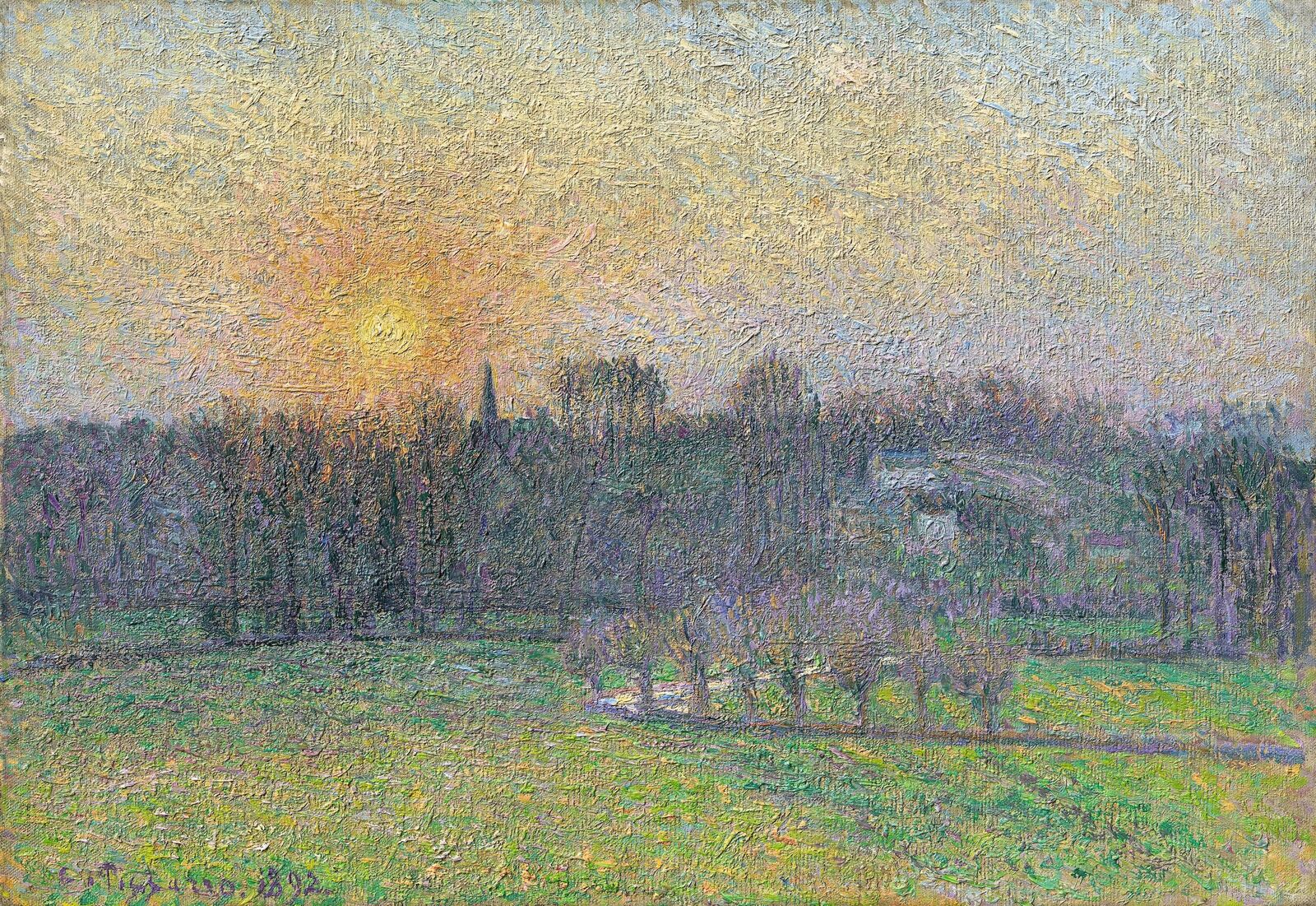

Meadow at Éragny with Cows, Fog, Sunset, 1891, Private Collection, Switzerland

Pissarro’s painterly development took a new turn in 1885 when he met the artists Paul Signac and Georges Seurat, who were young enough to be his sons. He was fascinated by their approach: inspired by current scientific discoveries in the field of optics and color theory, they juxtaposed tiny dots of paint in pure hues, allowing the colors to mix not on the palette, but in the viewer’s eye. Pissarro embarked upon the adventure of Neo-Impressionism. The other Impressionists remained skeptical.

It’s curious, this work with the dot—with time, with patience, little by little, one achieves an astonishing softness.

Hoar-Frost, Peasant Girl Making a Fire, 1888, Hasso Plattner Collection, Museum Barberini, Potsdam

The winter day is both sunny and icy. A small fire of twigs and branches offers warmth.

Heat and cold, light and shadow, distance and proximity: Pissarro combines opposites into a shimmering play of colored dots. For him, the Neo-Impressionist technique was a further development of Impressionism. His primary concern was to achieve what he called a “synthesis,” a blending of opposites into a harmonious pictorial unity—a goal he had long pursued.

To seek a modern synthesis through methods grounded in science, based on the color theory discovered by M. Chevreul and after the experiments of Maxwell and the measurements of N. O. Rood. . . . Because optical mixing evokes much more intense luminosity than the mixing of pigments.

Flooded with sunlight: Pissarro found his motifs in the region around his home.

In dramatic backlight, a herd of sheep raises a cloud of dust in the village street.

What the Neo-Impressionists are trying to do is synthesize the landscape into a definitive appearance that perpetuates the sensation.

Painting in the Neo-Impressionist style proved time-consuming and tedious and required the artist to adopt a highly regimented process. Over time, Pissarro began to feel constrained in his spontaneous sensations and limited by this rigid system of color dissection. After four years, he abandoned the stylistic experiment. But the experiences he had gained enriched his work, and from then on he incorporated aspects of this new approach into his painting.

After many years of frequent moves, Pissarro finally found a permanent home in the small village of Éragny-sur-Epte northwest of Paris near the border of Normandy. There, he was finally able to set up a large studio in the renovated barn. This step was all the more important since the aging artist suffered from a chronic eye condition and was unable to work outside during some phases of his career. Pissarro continued to paint directly from the motif, but now from the window, gazing out at the world.

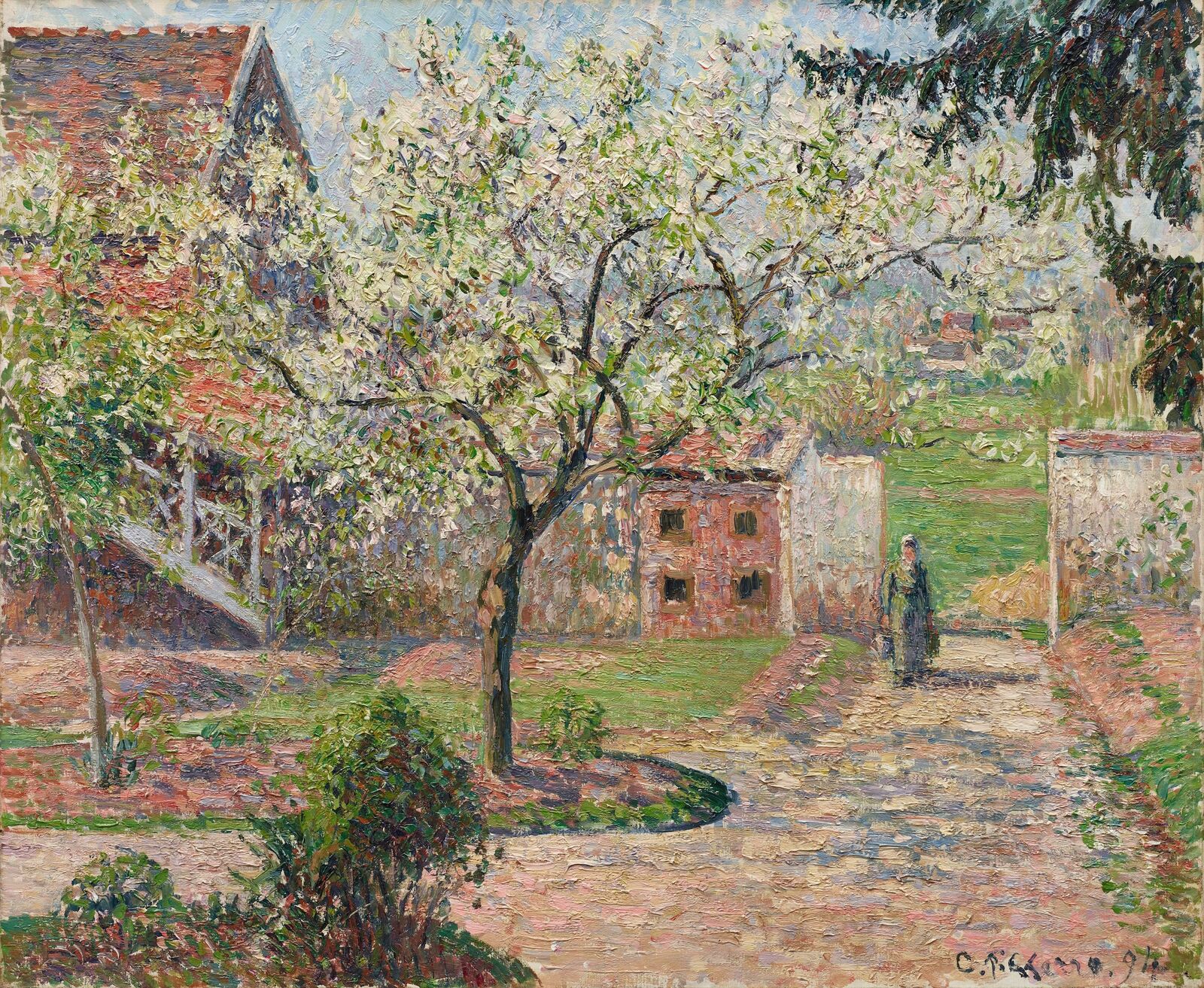

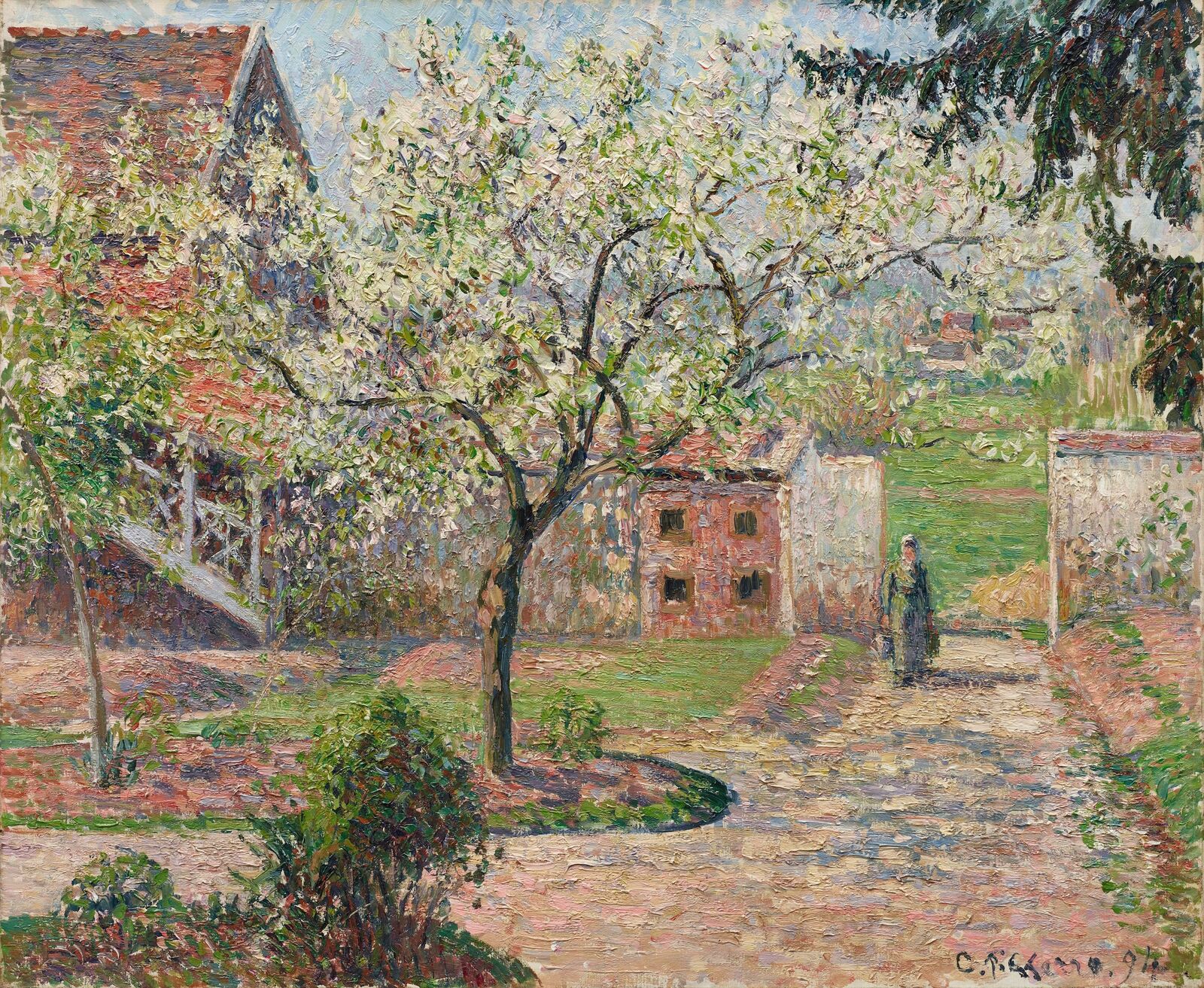

Plum Trees in Blossom, Éragny, 1894, Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen, © Heritage Images / Fine Art Images / akg-images

A view of the garden: fruit blossoms in Éragny!

The house in Éragny appears in numerous paintings by Pissarro. Surrounded by fields, the property also had a large garden where the artist’s wife Julie grew vegetables and fruits and sometimes kept chickens. At first, the Pissarros only rented the home; ultimately, however, they were able to buy it with the help of a loan from Claude Monet. It was Julie Pissarro who seized the initiative and asked for financial assistance, without first discussing it with her husband.

It’s a first-rate atelier, but I keep saying to myself, what’s the point of having a studio? In the old days, I did my painting anywhere; in every season, in sweltering heat, under rain, in horrid cold spells. . . . Am I going to be able to work in this new environment???

Delight in the details: grazing cows, gnarled fruit trees, and fenceposts.

The snow transforms the landscape and gives rise to new effects of color.

The intense brightness of the setting sun lends a celebratory atmosphere to the evening scene.

Pissarro was inspired by the rural environment of Éragny. A short stroll away on the other side of the small river Epte lay the neighboring village of Bazincourt. Pissarro returned to the same location again and again, creating numerous variations of a motif over a period of years. The scene shows a slice of nature shaped by the work of human hands, with pastureland, orchard meadows, and rows of trees.

Avenue de l’Opéra, 1898, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Reims, Vermächtnis Henry Vasnier, 11/1907

Photo: Christian Devleeschauwer

The swirling metropolis of Paris! Only late in his career did Pissarro discover the city as a motif—but then dove into it head first. No other Impressionist created so many scenes of the epicenter of modern life. From rural Éragny, Pissarro took the train into Paris, not least of all in order to maintain contacts in the art world. His dealer Paul Durand-Ruel encouraged him to paint entire series of boulevards and squares, since the new urban motifs sold well. The painter also depicted the bustling port cities of Rouen and Le Havre.

I am delighted to attempt these Parisian streets that are generally thought of as ugly, but which are so silvery, so luminous, and so alive—so fully modern!!!

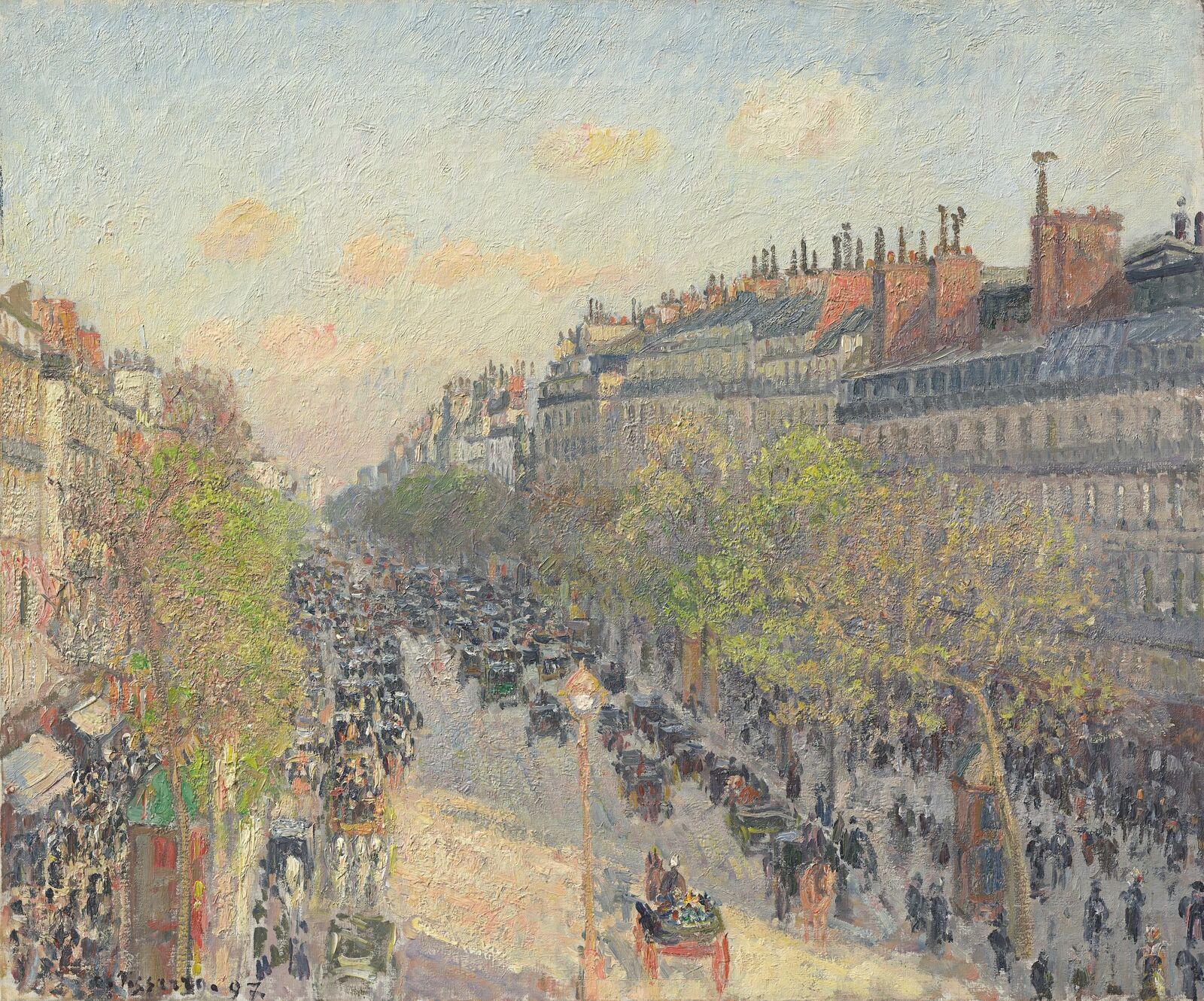

Boulevard Montmartre, Twilight, 1897, Hasso Plattner Collection, Museum Barberini, Potsdam

Pissarro spent over two months painting the lively Boulevard Montmartre, producing a total of sixteen views.

Boulevard Montmartre, Mardi Gras, Sunset, 1897, Kunst Museum Winterthur, Ankauf, 1947, © Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zurich, Martin Stollenwerk

On Mardi Gras, the boulevard is black with crowds of people.

What makes a city? Pissarro explored this question in multiple series of paintings. For his cityscapes, the painter preferred to work from a hotel room high above the street. He painted up to a dozen canvases at a time, seeking to capture the changing effects of light and weather. With its houses and splendid buildings, the urban structure of Paris served as a backdrop for what was more important to Pissarro: the life of the inhabitants. For him, the city belonged to everyone, not merely to wealthy bourgeois flaneurs.

I wonder if Durand is going to reject my next series of paintings; I’m feeling discouraged because there isn’t a single other dealer willing to do business! . . . People think I’m rich, but it’s always a struggle to make ends meet.

The Pont Neuf, built in the sixteenth century, is the oldest bridge in Paris.

Pissarro used energetic brushstrokes to capture the fleeting, rapidly changing impressions. The artist devoted an extensive series to the Pont Neuf, an important transport axis in Paris. He chose an elevated vantage point, surveying the scenery and depicting it from a distance. The shimmering sky fills almost half the canvas: it, too, offers a drama of constant change.

Cities have a distinctive physiognomy—transient, anonymous, bustling, mysterious—that must tempt the painter.

The Anse des Pilotes, Le Havre, Morning, Sunshine, Tide Rising, 1903, Musée d’art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre, © MuMa Le Havre / Florian Kleinefenn

The life of a modern port, with spectators along the quay, and a public toilet in the foreground.

Pissarro painted his final series of paintings in Le Havre in 1903. There the artist had first set foot on French soil at the age of twelve on his way to boarding school near Paris. Now, as an aging painter, he returned to this place, observing and experiencing the port city in the throes of rapid change. Two of his views were purchased by the local museum—Pissarro’s first sale to a museum in France.

I sometimes have horrible fears of turning a canvas around, always dreading I’ll find a monster instead of the precious jewel I thought I’d made! . . . Yet there are moments when I truly find relief in seeing certain things very solid and very much in keeping with my character. But enough of that. Painting, art in general, enchants me; it’s my life. What does the rest matter?