Unicorn:

For millennia, humans have been fascinated by the question: Do unicorns exist? And what might they look like? The trail of the unicorn leads through the whole history of European art and culture. As a mythical beast, subject of inquiry, and object of fascination, the unicorn has continually exerted its magic and remains a cultural phenomenon to this day.

Upper Rhine (Basel), Wild Men and Fabulous Beasts, ca. 1430–40, MAK—Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna © MAK, Vienna/Ingrid Schindler

When unicorns were colorful: a medieval tapestry.

As a creature among animals, it was sighted, variously described, and repeatedly represented in visual art. It was idealized and called into doubt. The unicorn cannot be captured, even today. It lives in the imagination. Yet as gentle as this marvelous animal may be, it is also portrayed as powerful, self-willed, and changeable in works of art from antiquity to the present.

One thing is certain: to follow the trail of the unicorn is to be lured into unknown territory. Dreams, desires, and longings are awakened by the marvelous creature with a single horn. Long ago, it was said that the unicorn could only be tamed by a virgin. And today? The unicorn proves that the boundary between reality and imagination is still permeable.

Gentle and graceful: a fire-gilded unicorn from Tibet.

Heraldic unicorn: the embodiment of positive traits.

Ready to spring: unicorns can be strong and powerful.

“Now I will believe / That there are unicorns.”

Flemish (Brussels), Unicorn and Stag, ca. 1500, Private collection, courtesy of Sayn-Wittgenstein Fine Art, New York

The unicorn is an extraordinary being. Its distinguishing feature—the horn in the middle of its forehead—is unmistakable and quite literally stands out. It has only one horn, and not two—but beyond that, there is no unanimity as to its appearance. The unicorn is a species marked by considerable biodiversity and variation of form.

Maerten de Vos (1532–1603), Unicorn, 1572, Staatliche Schlösser, Gärten und Kunstsammlungen Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Schwerin© Staatliches Museum Schwerin SSGK/Ulrich Pfeuffer

A majestic apparition: the Netherlandish artist was familiar with the description of the unicorn by the ancient writer Pliny (first century)

“Single-horned animals have the horn in the middle of the head.”

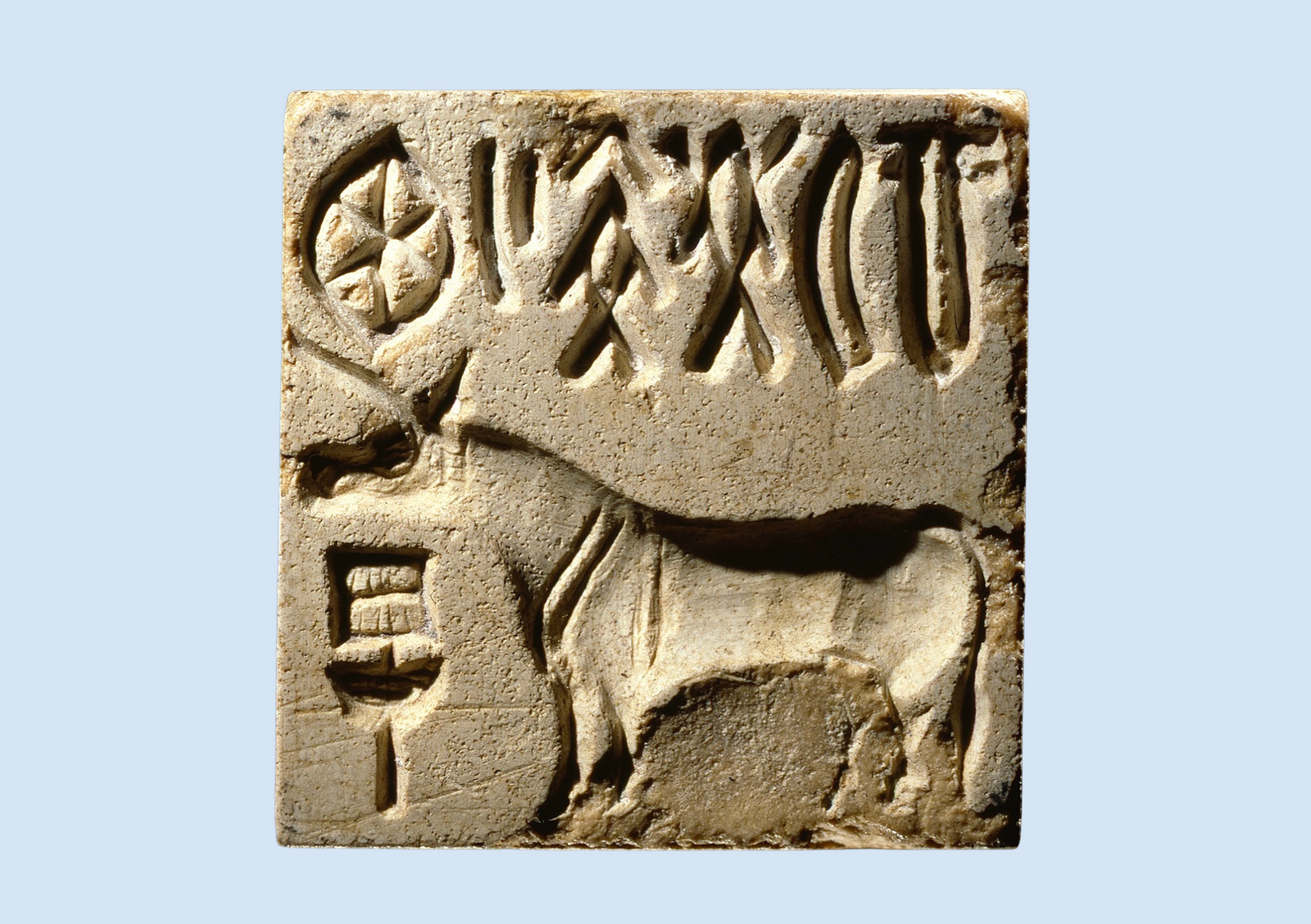

The unicorn can assume a wide variety of forms: it can have a goatee or the feet of an elephant, the tail of a horse or that of a boar. The idea of the unicorn originated in India over 4,000 years ago, and from there it spread to Tibet, China, Japan, and Persia. On its journey across space and time, it underwent astonishing transformations.

4,000-year-old clay: the earliest images of the unicorn are found on ceramic seals from the Indus civilization.

Warding off evil spirits: the qilin is an important figure in Chinese culture.

The Japanese kirin: an ivory unicorn as a good-luck charm.

French, Different Varieties of Unicorn, in Pierre Pomet (1658–1699) Histoire générale des drogues, traitant des plantes, des animaux, & des minéraux (General History of Drugs, Dealing with Plants, Animals, and Minerals), Paris: Jean-Baptiste Loyson and Augustin Pillon, 1694, Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel

Will the real unicorn please stand up? Seventeenth-century scholars in Europe still debated the animal’s true appearance.

“This animal has a horn on its forehead about a cubit in length. The lower part of the horn . . . is quite white, the middle is black, the upper part, which terminates in a point, is a very flaming red.”

The unicorn arrived in Christian Europe with the description in the Physiologus, a text from the second or third century. But how does this extraordinary creature actually look? Is its coat reddish, or a pure, flawless white? Does it resemble a small goat, or is it the size of an elephant? Since the year 1500, the unicorn has generally been depicted in horse-like form—though other, future transformations should by no means be ruled out.

“It likes lonely grazing grounds and wanders there in solitude . . .”

A medieval manuscript shows the unicorn as an animal created by God.

Master of the Flemish Boethius (active in the last quarter of the fifteenth century), God the Father with Adam and Eve in Paradise, in Flavius Josephus (first century), Antiquités judaïques et Guerre des Juifs (The Antiquities of the Jews and the Jewish War), 1480–83, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département des Manuscrits

Whether Creation, the Garden of Eden, or Noah’s Ark: since the Middle Ages, Christian iconography has always depicted the unicorn as one animal among many. The unicorn is even mentioned several times in the Bible—one of the reasons its existence was scarcely doubted until the seventeenth century.

“But who is the unicorn except the only begotten Son of God . . .”

In the development of Christian iconography, the unicorn even came to symbolize Christ. According to a traditional legend, this marvelous creature could only be captured by a “pure virgin”—a figure associated with Mary, the mother of Jesus. Countless images in prayer books and on altarpieces show the unicorn at her side. For medieval theologians, the unicorn represented the Incarnation of God and the virgin conception of Jesus in the womb of the Madonna.

The unicorn as a Christian symbol in a Netherlandish prayer book.

The mystic unicorn with the Virgin Mary on a glass painting from Freiburg.

The spectrum of images extends from the Annunciation to the unicorn hunt in a hortus conclusus, an enclosed garden. These lively, detailed scenes are often charged with multiple layers of symbolism. Such depictions appealed to a broad public, but could also show considerable theological and intellectual complexity.

“If you would know who this unicorn is, / it is our dear Lord Jesus Christ”

Central German (Erfurt), The Annunciation to Mary in the Allegory of the Unicorn Hunt, second half of the fifteenth century, Hohe Domkirche zu Erfurt, Domkapitel © Dombauamt, Bildarchiv, Erfurt/Falko Behr, Erfurt

A unicorn from the cathedral of Erfurt: inscriptions on banderoles explain the complex symbolism of the monumental altarpiece.

“. . . and if God so willed, unicorns could also exist.”

The unicorn has special facets of meaning when it appears in the company of women. Many pictorial representations celebrate the intimate companionship of a noble lady and the graceful, magical animal. The unicorn nestles softly against the woman, who tenderly embraces it: the two seem made for each other. But do such images suggest maternal care, or seduction? Encounters of this kind can have many nuances of meaning. In the poetry of the medieval minnesingers, the “hunt of love” mingled erotic overtones with the unicorn motif; yet themes such as marital fidelity and moral self-control could also come into play. The motif of woman and unicorn reached its zenith between 1350 and 1550—before being revived and reinterpreted by modern artists in more recent times.

“. . . for the love it bears to fair maidens [the unicorn] forgets its ferocity and wildness; and laying aside all fear it will go up to a seated damsel and go to sleep in her lap.”

Italian (Veneto), Virgin with Unicorn, ca. 1510, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In tender melancholy and quiet togetherness: the unicorn in female company.

Mysterious and ambiguous: the unicorn seeks the company of women.

The girls by whose means the unicorn is captured must be nobles, not country girls. . . . The unicorn loves them, because it knows they are gentle and sweet.”

Flemish or Lower Saxon (?), Virgin with Unicorn at the Spring and Groups of Hunters, late fifteenth century (?), Evangelische St. Gotthardt- und Christuskirchengemeinde, Brandenburg an der Havel © Hans-Uwe Salge, Brandenburg an der Havel

A noble lady with a white unicorn: the tapestry from Brandenburg an der Havel may have been made for a young woman entering a convent.

Northern French (Dieppe), Map of the East Coast of North America, in Zeeatlas (Atlas de Dauphin) (Sea Atlas [Atlas of the Dauphin]), ca. 1538, KB Nationale Bibliotheek, The Hague

No Europeans had ever seen a unicorn with their own eyes. But ancient writers had asserted that the rare animal exists—and so it must live elsewhere, far away, in distant lands! The reports of travelers fueled belief in the unicorn, while convincing illustrations authenticated their descriptions. Maps of non-European territories illustrated unicorns as a matter of course.

“Therefore, credence must be given to what travelers and distant sojourners say: for the animal is indeed on earth, otherwise none of the horns would exist.”

Unicorn Horn from Saint-Denis, before the mid-thirteenth century, Musée de Cluny—musée national du Moyen Âge, Paris

Over two meters long: this imposing horn belonged to the treasury of the church of Saint-Denis near Paris.

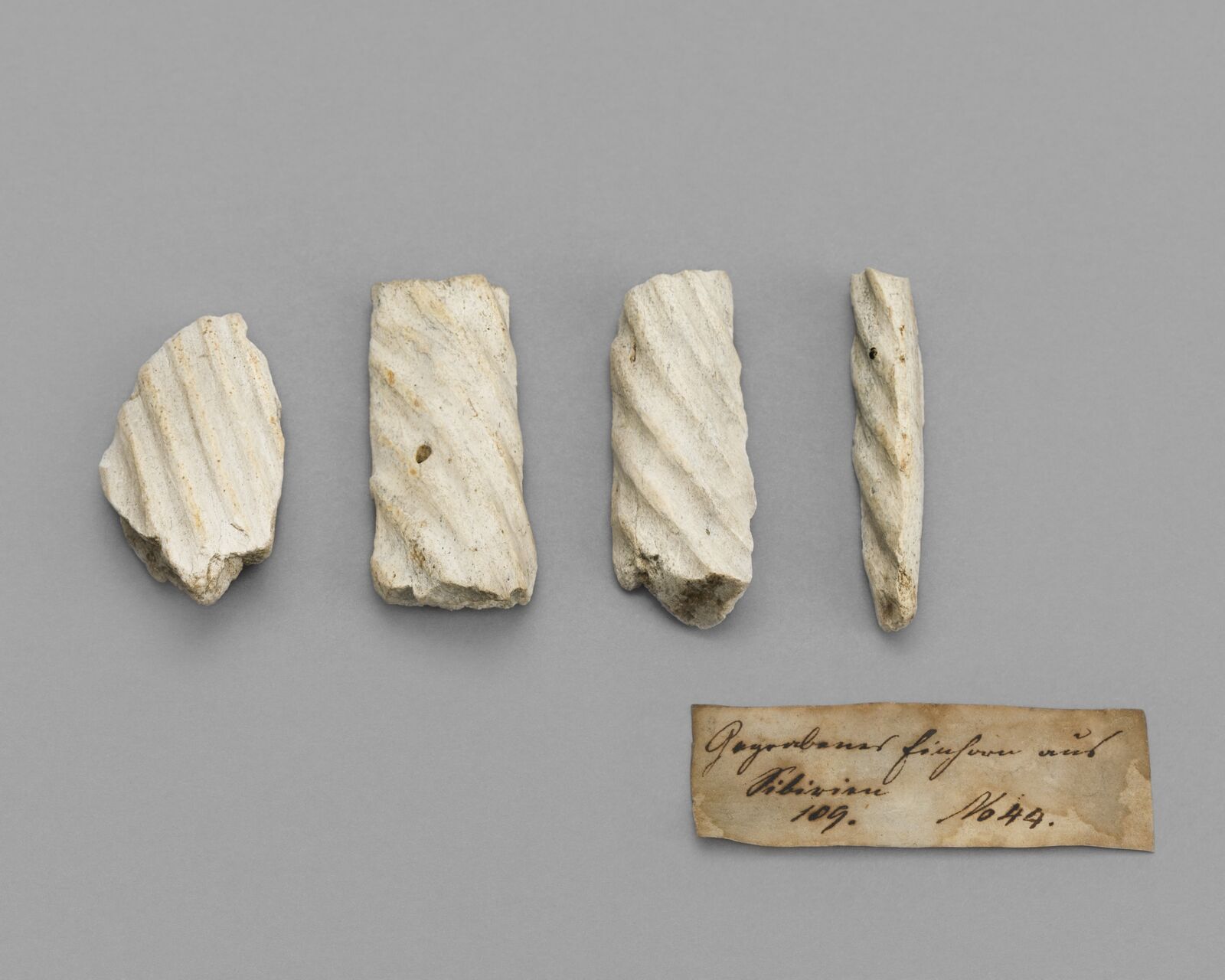

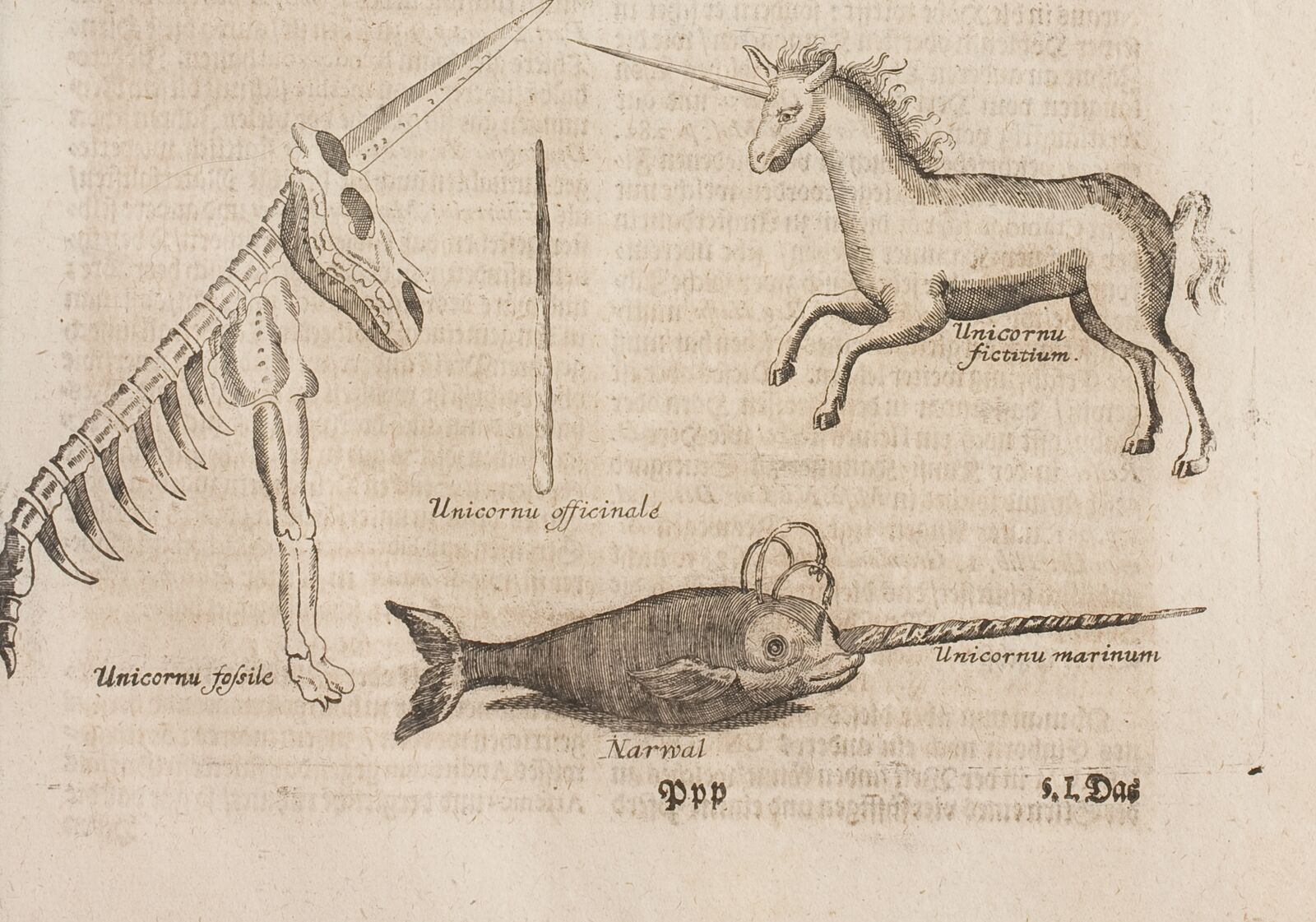

There even seemed to be concrete proof—in the form of the long, pointed, spiral horns held in church treasuries and princely chambers of art. The preciousness, extraordinary form, and rarity of such objects were viewed as confirmation of the unicorn’s existence. Not until the sixteenth century did the first scientists begin to suspect that in reality, these so-called “unicorn horns” were actually narwhal tusks. Traditional textual sources and conventional understandings of the world were increasingly called into question. Doubts proliferated, skepticism grew.

Joachim von Sandrart (1606–1688), Large Fish Market, ca. 1654–55, Inscribed lower right: von Sandrart, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Gemäldegalerie

A narwhal tusk, fished from the sea: the painting reflects the latest scientific discoveries.

Another century of lively debate would pass before scientists could agree that the unicorn was an invented animal. A sobering recognition—but at the same time, a liberating one: the unicorn, once believed to be extinct, could now live on as a mythical beast despite all the empirical evidence to the contrary, resilient in the face of scientific proof.

Fossil finds from Siberia: fragments from a princely collection in Saxony show the typical spiral form.

Colorful sea unicorn: a fifteenth-century illustration of a narwhal.

German (Frankfurt am Main?), Von dem wahren und gegrabenen Einhorn (On the True and Excavated Unicorn), in Michael Bernhard Valentini (1657–1729) Museum Museorum, Oder Vollständige Schau-Bühne Aller Materialien und Specereÿen . . . (Museum of Museums, or Complete Theater of All Materials and Species), Frankfurt am Main: Johann David Zunner, 1704, Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel

The state of the research in 1704: a medical professor describes the four-footed beast as Unicornu ficitium, or “invented unicorn”.

“. . . whoever desires a unicorn / may find it between the ice floes of Greenland.”

“And in the morning after sunrise, the unicorn comes, dips its horn in the aforementioned river, and in this way expels the poison from it. . . . I saw it myself.”

From about 1600 on, increasing numbers of apothecaries were named after the unicorn, and some still bear that title even today. Rare unicorn horn was once considered a powerful remedy for nearly every disease; its medical efficacy was emphasized already in the earliest sources. Whether for epilepsy or other incurable illnesses, it could be administered in powdered form, pulverized from “real” unicorn horn. Even Martin Luther relied on this miracle cure.

Austrian (Zwettl), Apothecary Symbol of a Unicorn Head with Narwhal Tusk, ca. 1720, Zisterzienserstift Zwettl, Stiftsammlungen

Healing under the sign of the unicorn: an apothecary in Austria attracted customers with a real narwhal tusk.

Even the deadliest poisons, it was believed, could be neutralized by the power of the unicorn. Since princes and potentates lived in constant fear of poisoning, they had drinking goblets made of unicorn horn or used a piece of the horn to test questionable victuals. As the number of narwhal tusks imported to Europe increased throughout the course of the seventeenth century, the price of the material dropped dramatically.

“Everyone knows how powerful the horn is against venom.”

Southern German, Vessels for True Unicorn (Unicornu verum) and Buried Unicorn (Unicornu fossile), ca. 1740, Deutsches Apotheken-Museum, Heidelberg

From the medicine cabinet: “true unicorn” was a costly and sought-after remedy.

Southern German (Nuremberg?), Bentwood Box for Precious Unicorn Powder, eighteenth / early nineteenth century, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg

Even in the early nineteenth century, some still trusted the old magic: this bentwood box for “fine unicorn powder” comes from the Stern apothecary in Nuremberg.

“. . . for His Imperial Majesty had a unicorn horn set in gold next to him at the table at all times, and when a dish mixed with poison was set before him, the unicorn horn began to sweat.”

Barefoot astride a unicorn: the hairy Wild People of the late Middle Ages represented unfettered nature.

Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet (Master of the Housebook), active ca. 1475–ca. 1500, Wild Man on a Unicorn, 1473–77, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

“. . . for thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns.”

The unicorn is not always gentle, trusting, and peaceful: on the contrary, ancient authors emphasize its wildness and aggressiveness in some situations. The unicorn’s fierce, threatening nature is strikingly portrayed in artistic images into the sixteenth century.

Workshop of the Flammschweiflöwe (Nuremberg), Aquamanile in the Form of a Unicorn, first quarter of the fourteenth century, Musée de Cluny—musée national du Moyen Âge, Paris

Flaming tail and shaggy mane: a pouring vessel for ritual handwashing.

The unicorn unleashes its ferocity against humans, animals, and even its own kind. Only the so-called “Wild People” of the late Middle Ages—mythical forest-dwellers whose bodies were entirely covered in hair—could live with the unicorn and even ride it. In the conceptual world of that era, the Wild People represented the antithesis of civilized human society.

“One cannot protect oneself from it or approach it with any weapon, so fierce is this animal, so strong, so wrathful, and so proud, and so fearless . . .”

According to a medieval romance, 8,450 unicorns were slain by Alexander the Great and his men in a mighty battle.

In the Persian epic Shāhnāmā (Book of Kings), the hero Prince Gushtāsp must hold his ground against a monstrous beast . . .

The unicorn boldly attacks dragons, lions, and especially the elephant. Tales of the “wild unicorn” were likely based on early reports of the rhinoceros. Heroic legends from Europe and Persia tell of lone warriors who courageously battle the dreaded beast. But who wins? The gallant tailor of fairy-tale fame defeats the unicorn by his wits alone, without recourse to weapons. In contemporary art, the mythical beast once again appears as aggressive and combative, a figure for identification in existential struggles.

A unicorn brutally assaults a deer.

The knight Saint George rides a unicorn into battle against a dragon.

Muscular physique: the triumph of the unicorn in sculptural form.

Militant and vulnerable: female self-determination in the company of a unicorn.

“Even an elephant is not safe from this horn, despite the size of its body. It sharpens its horn for battle by rubbing it on the rocks.”

Exquisite Showpieces

The unicorn held a special place in princely chambers of art and curiosities, known as Kunst- and Wunderkammer. Such collections were microcosms of the knowledge and mystery of the world and formed the basis of later museums. When princes and wealthy citizens in the Renaissance and Baroque began collecting marvelous objects of nature and art, the unicorn was among the most sought-after rarities.

Southern German, Unicorn Horn of Canon Andreas von Thüngen, sixteenth century, Gold mounting Nuremberg (?), circle of Wenzel Jamnitzer (1507/08–1585)?, Galerie Bernard De Leye, Brussels

A legendary find: an alleged unicorn horn from a noble collection.

Whether whole and intact as a “genuine” horn, artfully decorated with carvings, or repurposed into a drinking vessel, unicorn horn was considered the showpiece of a Kunstkammer. Also much coveted were the gleaming figures of unicorns fashioned of ivory, gold, or silver by a master’s hand. Such objects were manifestations of the marvelous in tangible form.

Showpiece at a princely banquet: the unicorn as Trinkspiel (drinking game).

Crafted narwhal tusk set in silver: drinking vessels of unicorn horn could allegedly neutralize poison.

Crowned with a unicorn: a princely wedding gift of gilded silver.

“And to tell you the truth, these horns which are shown to us . . . under the name of unicorn are different animals than those which are depicted for us in paintings.”

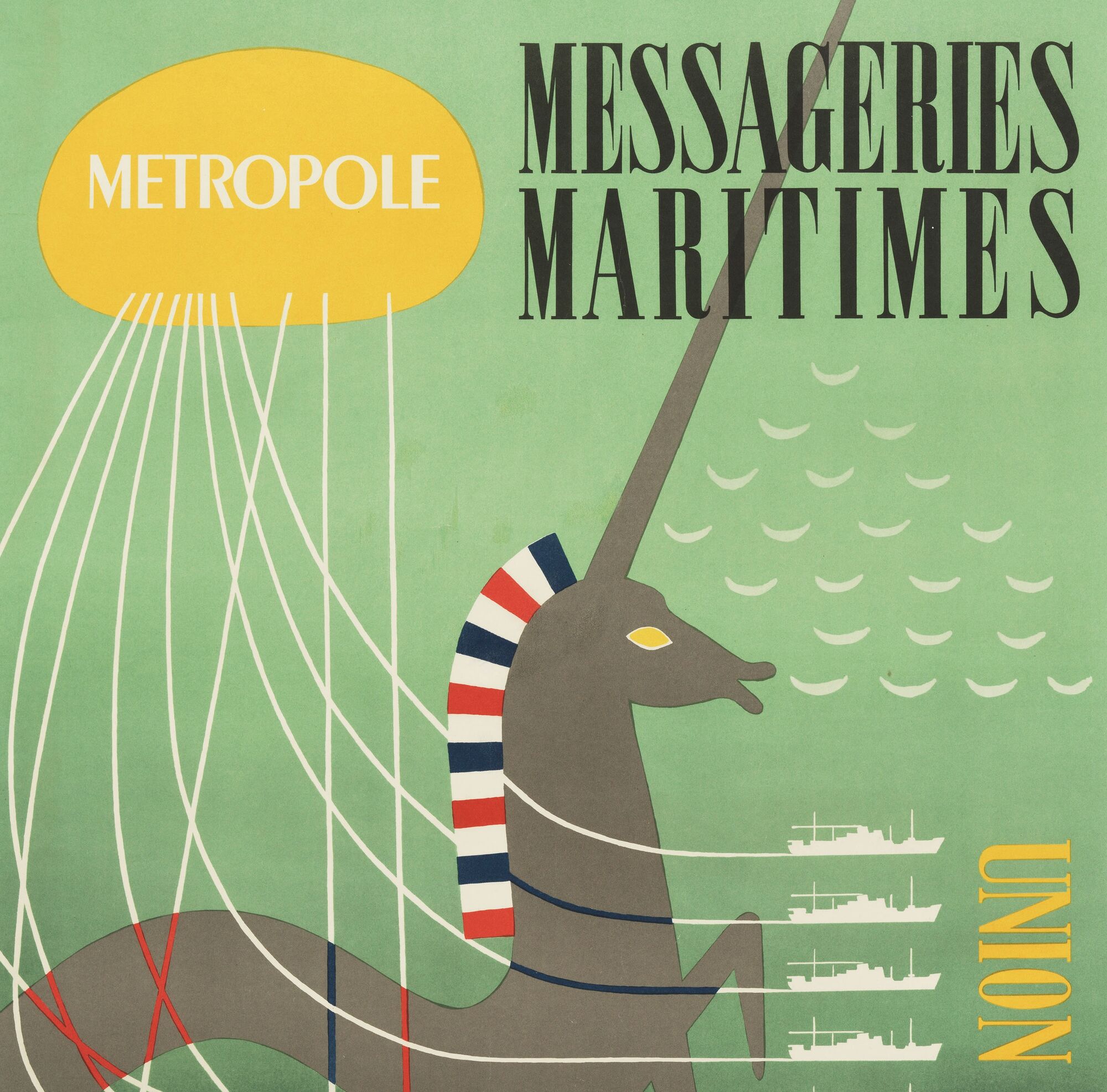

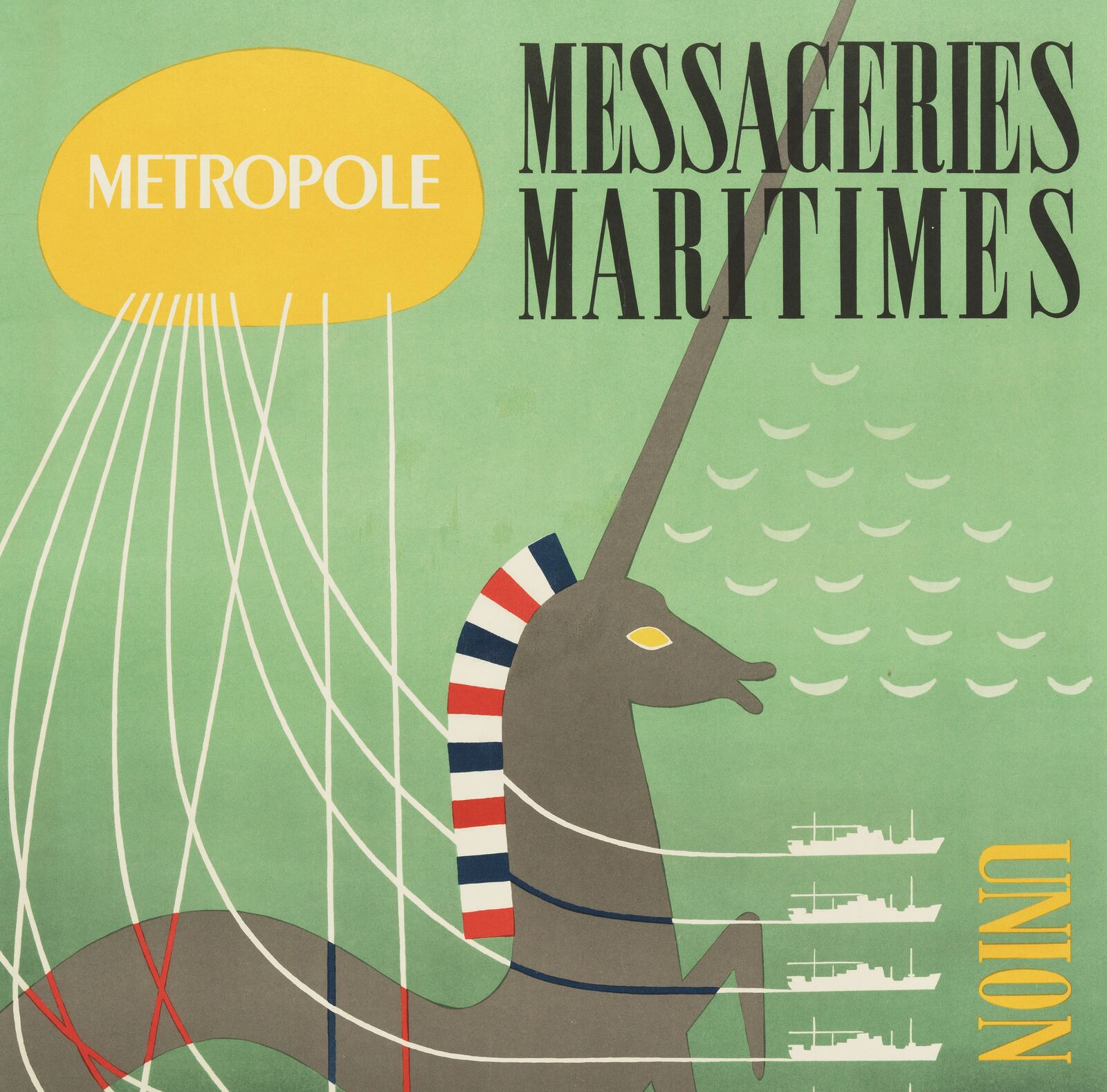

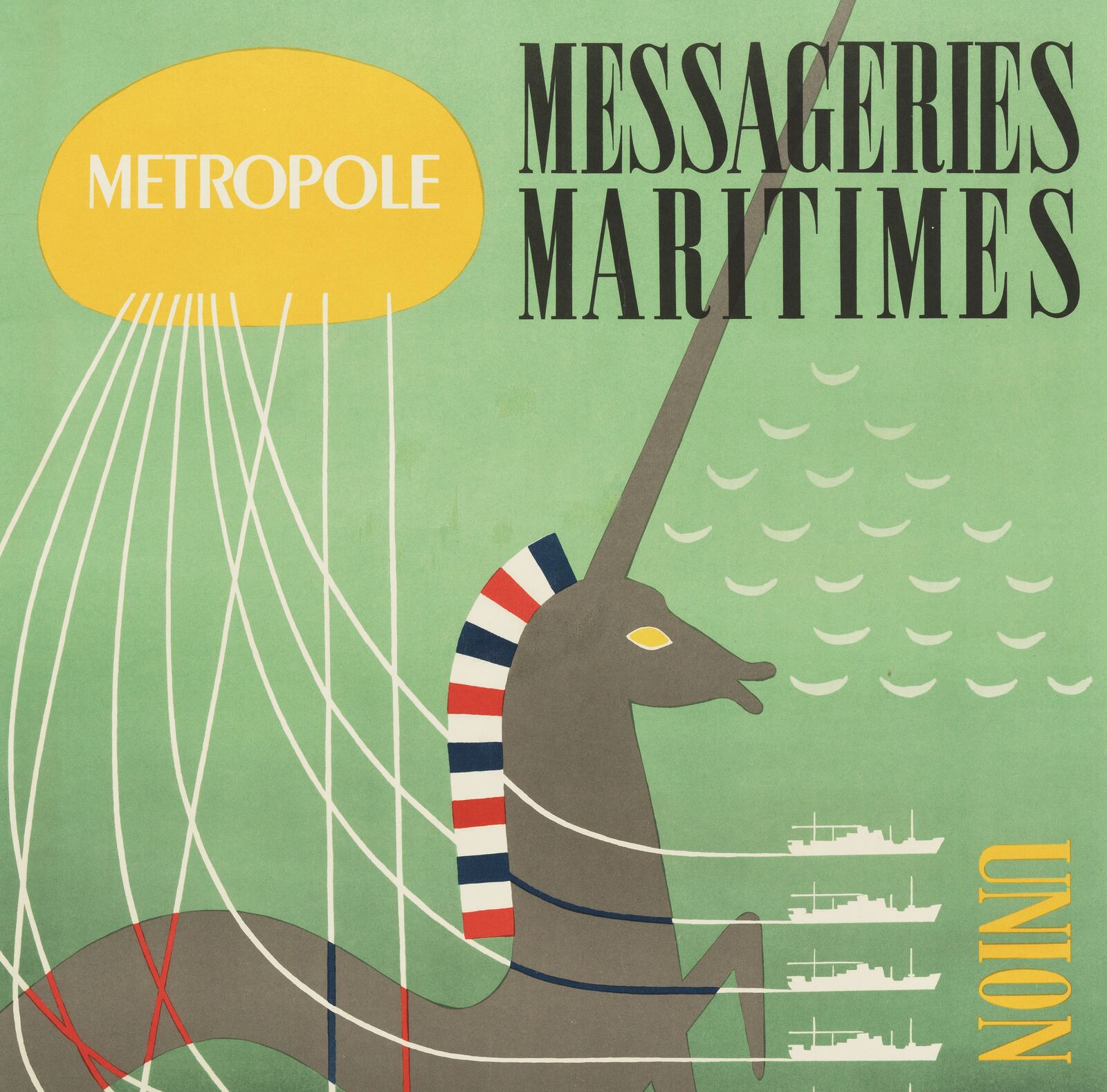

Poulain (active ca. 1950), Marine Unicorn of the Messageries Maritimes, Poster advertising for the shipping company, Messageries Maritimes, 1946–58, Private collection

As an imaginary creature, the unicorn has a special gift: it has always been open to differing interpretations and a wide variety of meanings. Over the course of the centuries, the unicorn has been associated with the most diverse themes and fields of activity: for example, it has served as a symbol of chastity and virtue, but could also stand for arrogance or other qualities.

French, Confrontation of Good and Evil, Virtue and Vice, ca. 1505, S. Franses, London © S. Franses Limited, London

Vices on the left, virtues on the right: the monumental tapestry visualizes complex ideas.

In the realm of politics, the unicorn triumphed as a heraldic animal for rulers. Always dazzling and capable of transformation, its cleverness and speed made it suitable even for twentieth-century advertising. The unicorn’s enduring popularity also arises from its graceful form: the pointed horn alone, jutting up like an exclamation point, draws attention to itself.

Agentur Le Globe (Paris), La Licorne, 1907–ca. 1915, Poster advertising the French car company, Corre La Licorne, Neuilly-sur-Seine, Private collection

Legendary speed: the unicorn as automobile advertising.

French, Unicorn Supporting a Coat of Arms, in Gradual of Robert de Croÿ, 1540, Le Labo—Cambrai, Bibliothèque classée de l’agglomération de Cambrai

A heraldic supporter: the unicorn often embodies positive qualities.

“These animals are very strong and swift. . . . At first they run slowly, but the longer they run their pace increases wonderfully, and becomes faster and faster.”

In more recent times, the unicorn has assumed new roles. The LGBTQAI+ community and marginalized groups have chosen it as a symbol and figure for identification, and it also serves as an emblem for the climate crisis. It has become a permanent fixture in children’s rooms as well as in pop and consumer culture, and in the digital world of the internet it lives on, open to new interpretations.

Unknown carver after a design by Helmtraud Wunderwald (1922–2016), Tailor and Unicorn, 1946 Figures for a diorama to the fairy tale Das tapfere Schneiderlein (The Gallant Tailor), Stadtmuseum Dresden, Museen der Stadt Dresden © Jens Ziehe, Berlin

A modern fairytale scene: the toy figure of the unicorn faces off against the gallant tailor.

René Magritte (1898–1967), The Meteor, 1964, Private collection

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

For centuries the unicorn was almost entirely absent from art, receding into distant memory with the waning of the Baroque period. Only toward the end of the nineteenth century did the legendary beast once again appear in the visual arts. Artists, who often perceived themselves as existing on the margins of society, now adopted the rare, enchanted unicorn as a figure for identification on their path toward modern art. In an age increasingly dominated by technology and rationalism, the magical animal embodies an alternate world: the refuge of the imagination.

Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901), The Silence of the Forest, 1885, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, Poznan

The unicorn steps into the light from a mysterious forest: Böcklin often combined the fantastical and the real with a touch of irony.

Armand Point (1861–1932), The Princess and the Unicorn, 1896, Lucile Audouy, Paris

The renaissance of the unicorn: born in Algiers, the artist belonged to the Symbolist movement in Paris.

“Why did they go away, do you think? If there ever were such things.”

“Who knows? Times change. Would you call this age a good one for unicorns?”

Modern images of the unicorn often echo traditional themes such as the close relationship between woman and unicorn. But as conventional gender roles are increasingly called into question, new facets and associations arise. In the contemporary world, manifestations of the unicorn can be gently ironic, surreal, or even completely abstract.

Self-confident: The unicorn portrayed by contemporary artist Marie Cecile Thijs.

The unicorn resides in the liminal regions of the world and moves in the margins of human existence. In its singularity, it embodies the possibility of being different and of diverging from the norm. In this way, the unicorn—an enchanted being that can live freely, just the way it is—offers us the opportunity to encounter difference with admiration.

Gustave Moreau (1826–1898), Woman and Unicorn, undated, Musée national Gustave Moreau, Paris

Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau was inspired by the recently rediscovered medieval tapestry series The Woman and the Unicorn, now in the Musée de Cluny.

“. . . the unicorn grazes on the hillside of the soul . . . “