A New Art

In the nineteenth century, many photographers chose the same motifs as Impressionist painters: the forest of Fontainebleau, the cliffs of Étretat, or the modern metropolis of Paris. Photographers, too, studied changing conditions of light and weather and used a variety of tricks in their ongoing quest for the perfect picture.

Dialogue and Rivalry

The newly invented technical medium laid claim to the status of art from the very beginning. Photography and painting spurred one another on: their interaction was marked by both rivalry and inspiration.

The exhibition sheds light on this fascinating development from the 1850s to the First World War. On view are masterpieces of early photography by Gustave Le Gray, Alfred Stieglitz, Louise Deglane, and Heinrich Kühn, works that show astonishing parallels to Impressionist paintings from the Hasso Plattner Collection.

The Barberini Prologue to the exhibition ...

... traces the interaction of photography and Impressionism. Whether on the beach, the boulevards of Paris, or a snow-covered field — their works capture the fleeting moment, and with it the spirit of modernity.

That photography is an entirely mechanical science (…) we cannot admit. (…) we believe that it will be on a par with the art of drawing (…)

The Normandy cliffs, here at Étretat, were already a tourist attraction in the 19th century.

Louis Alphonse Davanne: Étretat, Cliff to the Left, No. 2, 1864, Beaux-Arts de Paris

Majestic Expanses

Claude Monet: The Cliff and the Porte d’Aval, 1885, Hasso Plattner Collection

Like many photographers, Monet was fascinated by the craggy cliffs near Étretat and painted them under a variety of weather conditions.

As an expression of boundless expanse, images of clouds and the sea were associated with the idea of the sublime— nature as a majestic and untamable force. The ceaseless motion of the waves spoke to the Impressionists’ desire to capture fleeting sense impressions on the canvas as directly as possible. Early photographers likewise devoted themselves to the depiction of sky and sea and in so doing pursued both artistic and scientific ambitions.

One of the most important early photographers was Gustave Le Gray. From 1856 on, he produced a series of ocean images remarkable for their sharp detail and artistic quality. He was the first to capture nuanced images of the breakers. Since the sky and the sea had to be photographed with different exposures, Le Gray sometimes combined two negatives.

Gustave Le Gray’s training as a painter also showed in the perfection of his compositions.

A sensation in 1857: Le Gray captures sea spray in sharp focus.

... the grandest effort ever seen in photography.

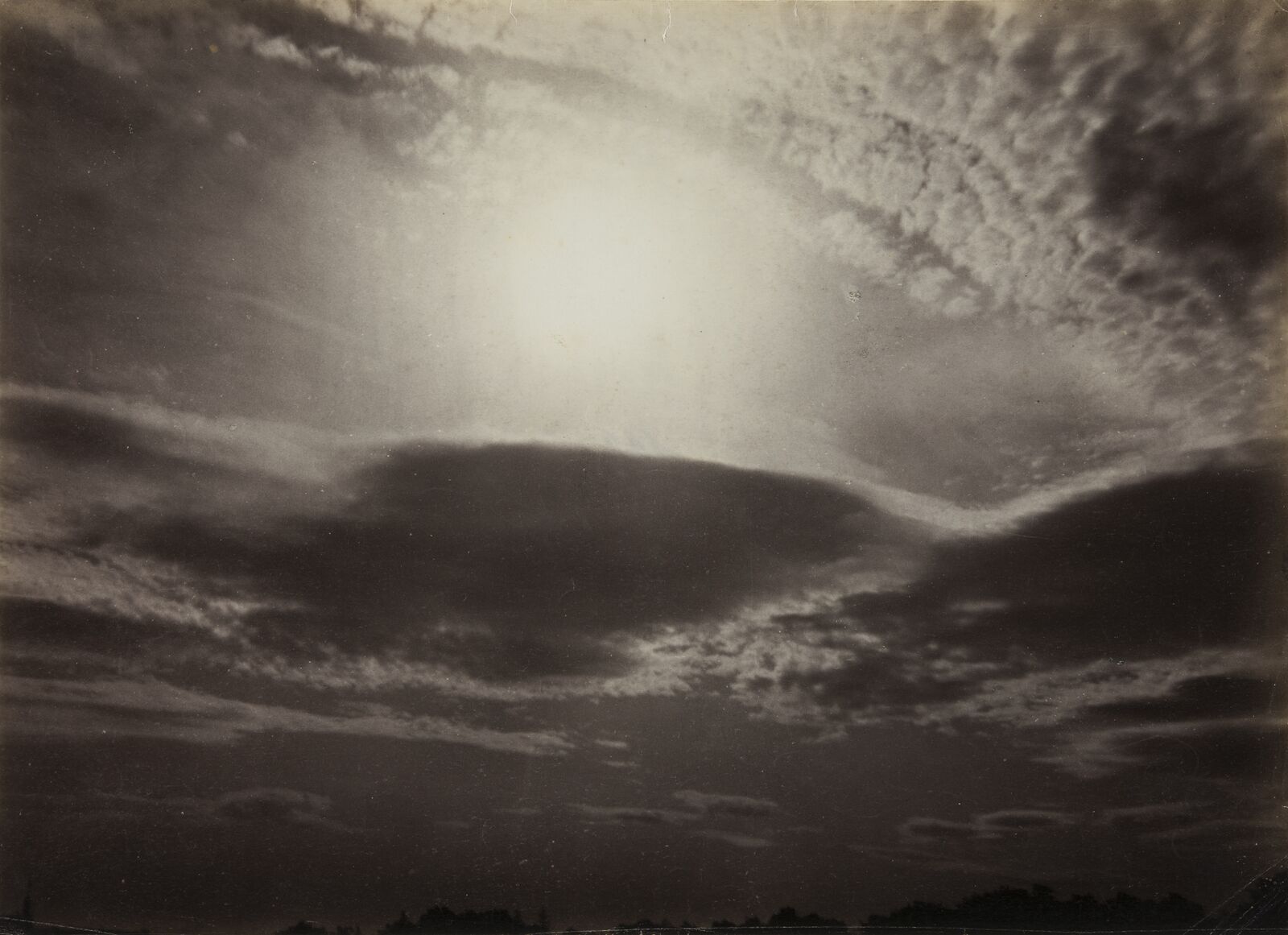

Photographers, like painters, experimented with different moods of light. In the early days it was impossible to take photographs at night due to the small aperture of the camera lens. In order to achieve a dramatic moonlight effect, Henry Stuart Wortley aimed his camera directly at the sun on a cloudy day.

Henry Stuart Wortley: How Sweet the Moonlight Sleeps upon the Wave, ca. 1869, Céline, Aeneas, Heiner Bastian

Henry Stuart Wortley poetically entitled his seascape How Sweet the Moonlight Sleeps Upon the Wave, an allusion to a line from Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice.

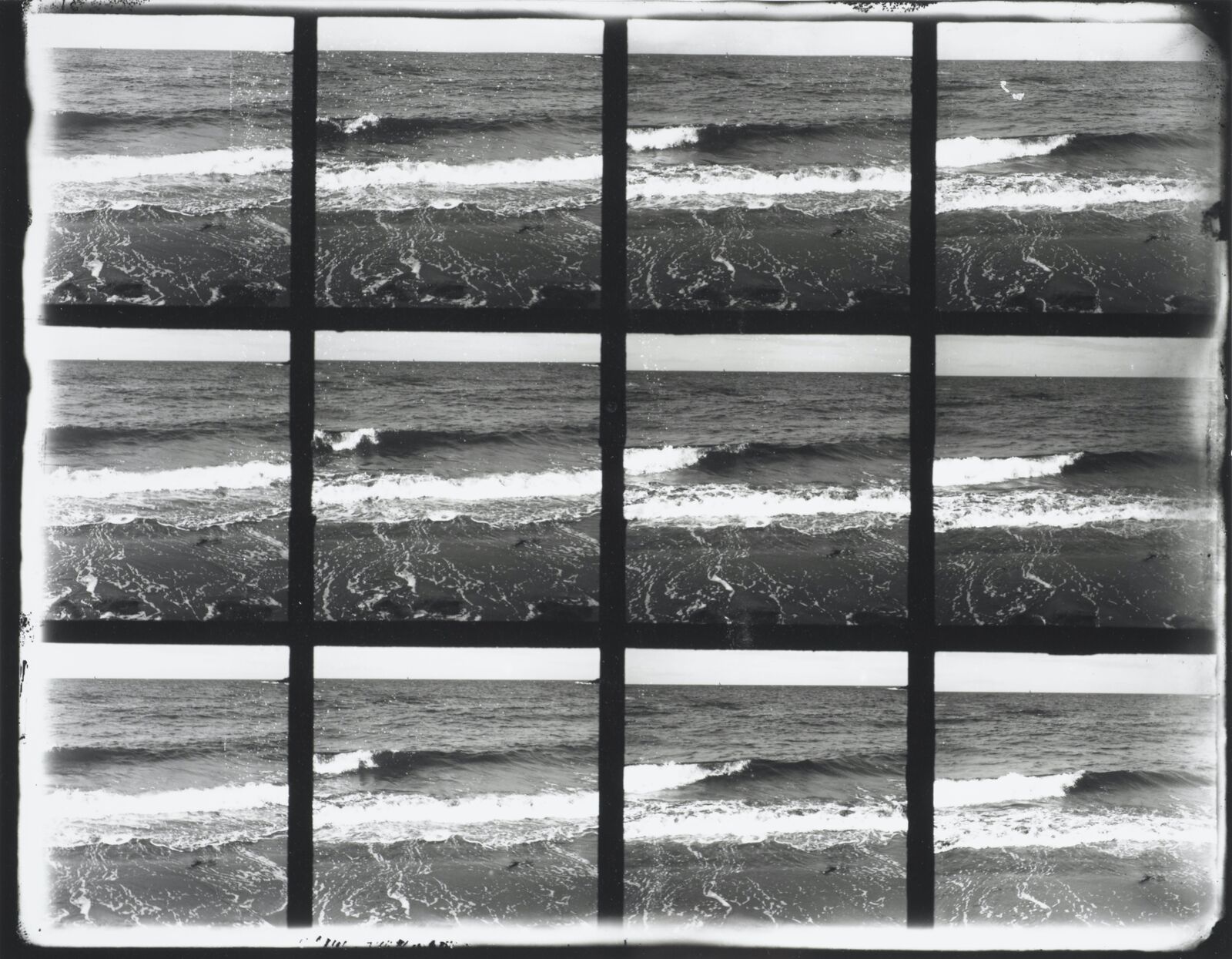

How does a wave break? Chronophotography used images photographed in rapid succession to record complex sequences of motion with greater precision than the human eye — a technique that was useful not only to natural scientists, but to painters as well.

Albert Londe: The Wave, 1893 (printed 1992), Beaux-Arts de Paris, © bpk / RMN - Grand Palais, / Albert Londe

For his photograph The Wave, Albert Londe used a camera with twelve lenses that he had constructed himself. The individual images were then exposed on a single glass plate.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the observation and study of clouds became the focus of scientific interest. Meteorological institutes were founded in Berlin, London, and Paris, and for the first time cloud formations were systematically classified — with the help of photography.

Carl Teufel: Cloud Study, Bavaria, ca. 1890, Münchner Stadtmuseum, Munich, Sammlung Fotografie

The southern German photographer Carl Teufel marketed his cloud pictures specifically as models for artists.

Alfred Sisley: The Meadow at Veneux-Nadon, 1881, Hasso Plattner Collection

Cumulus or cirrocumulus? Alfred Sisley’s paintings bespeak his precise observation of characteristic cloud formations.

The technical ability to capture fleeting phenomena of weather with ever greater precision made photography an important resource for meteorological research. Photographs of lightning not only led to new understanding of electrical discharges, but also transformed landscape painting: from then on, lightning was no longer depicted as a simple zigzag form.

Great technical skill and experience were needed to avoid overexposure when photographing the sky; Robert Scholz’s Cloud Study of 1870 is an outstanding achievement.

Spectacular discoveries: the scientist Emil Jacobsen used photography to study the duration and structure of lightning.

Results of "Hausmannization": The great Parisian boulevards had only been created in the course of a massive urban redevelopment in the 19th century.

Anonymous: Grand Boulevard, Paris, ca. 1875, Münchner Stadtmuseum, Munich, Sammlung Fotografie

Center of Modernity

Gustave Caillebotte: Rue Halévy, View from the Sixth Floor, 1878

This view of the Rue Halévy was painted by Gustave Caillebotte in 1878. The Impressionist shows the street in a dramatically foreshortened view from a sixth-story window. Photographers often chose very similar perspectives.

Paris was in the throes of radical change. From the 1850s on, entire streets of the medieval city center had been taken down, while ambitious new buildings in a uniform architectural style sprang up to take their place.

Wide boulevards and avenues brought light and air into the capital city; the streets, pulsating with life, were filled with rapidly increasing traffic. Around 1870, Paris was considered the most modern metropolis in the world. Photographers documented these profound changes.

(…) everywhere masonry fell with thunderous noise, clouds of dust darkened the heavens, workers shouted (…), cars laden with rubble plowed valleys of mud; (…) it rained rubble and bricks.

The photographer Charles Marville was commissioned by the municipal authorities of Paris to showcase the magnificence of the newly renovated city. His images, known for their technical perfection, are always devoid of human figures. The extremely long exposure times effectively excluded pedestrians in motion.

Charles Marville: Paris, Rue de Rivoli, ca. 1877, Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris

For this image, the photographer chose a location very close to the Louvre. The low angle of the camera emphasizes the broad expanse of the street.

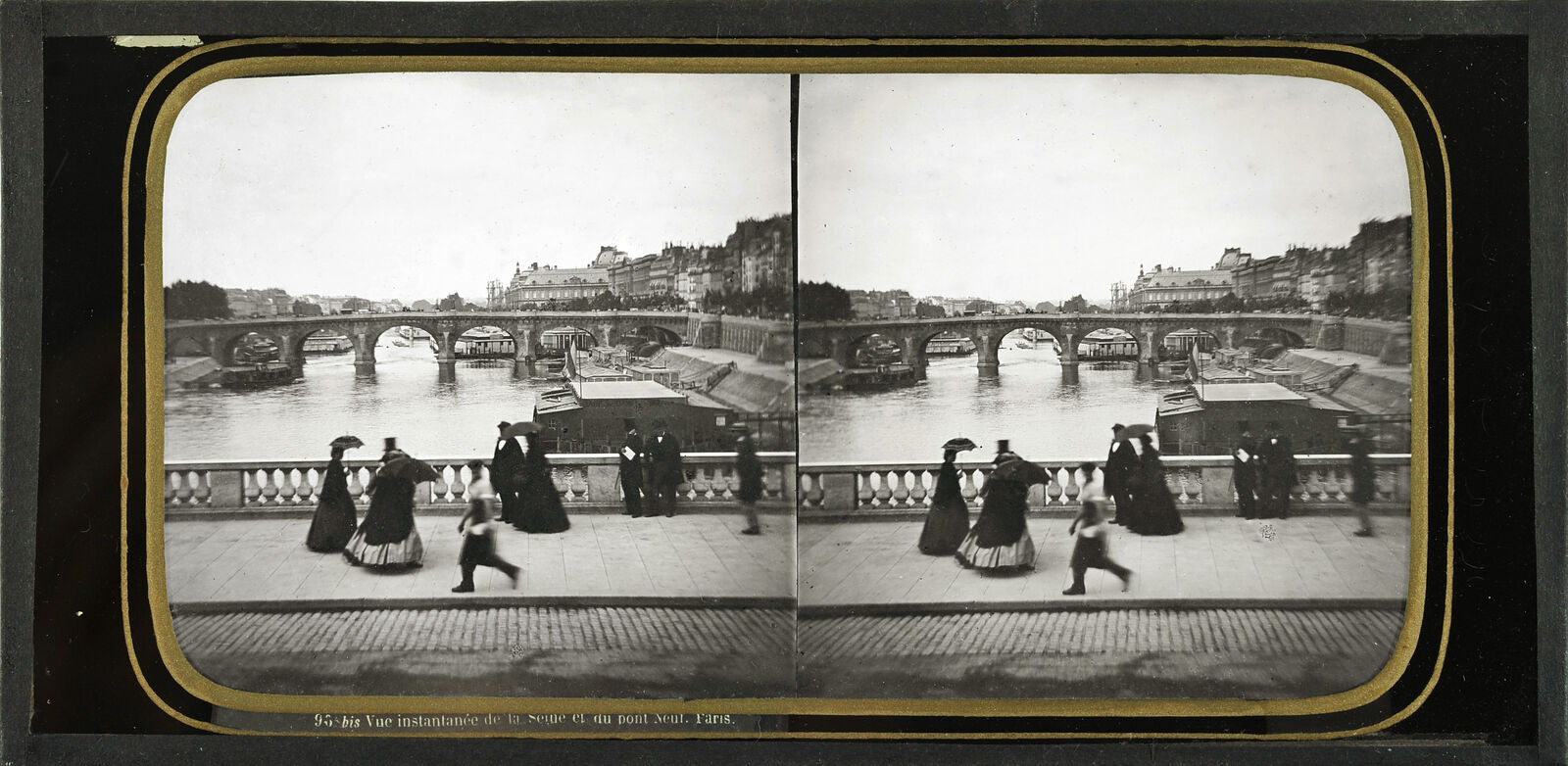

Stereophotographs were among the most popular images of the new Paris. With their short exposure times and small negative formats, these snapshots made possible the realistic depiction of motion and dynamism. Viewed through a special device, they conveyed an impressive three-dimensional effect.

Stereophotographs were the first mass medium in history and enjoyed tremendous popularity. This photograph was made in 1860 ...

... while Camille Pissarro depicted the busy Boulevard Montmartre in this painting from 1897, part of a series of fourteen works in which he painted the street under varying conditions of light.

Carriages, pedestrians, and the hustle and bustle of traffic: contemporary viewers were fascinated by snapshots of city life.

If we ascend the Arc de l’Étoile and look down on the Champs-Élysées, we see a number of (…) variously coloured specks stirring about on the roadway or pavements. That is all our eyes distinguish.

Jacques Henri Lartigue, later a famous photographer, was only seventeen when he captured this perfect snapshot in 1911.

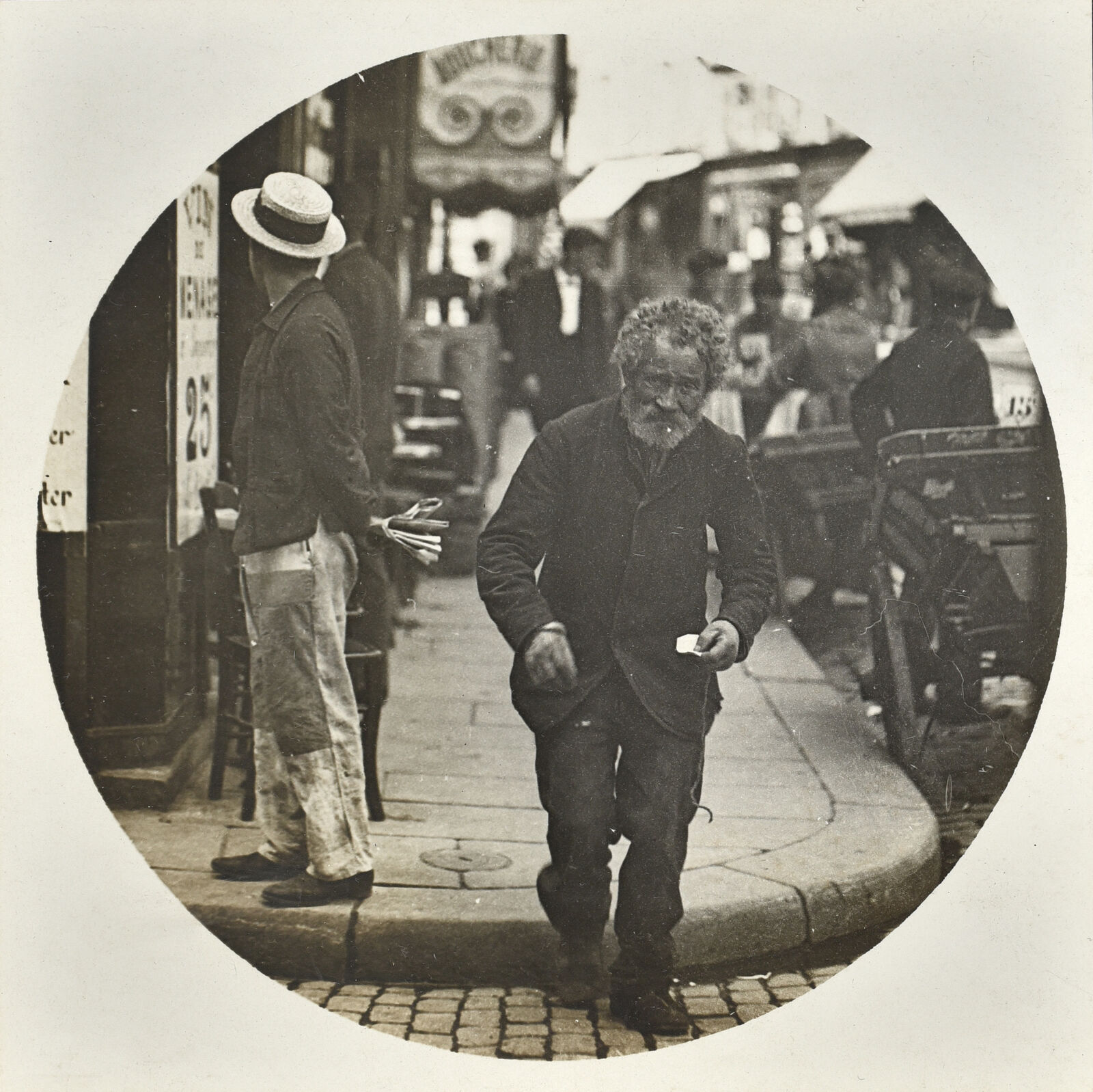

The camera could also document the dark side of the glittering metropolis, as in this photo by Louis Vert from around 1900.

Modern industrial architecture was a symbol of technical progress. Buildings of iron and steel were soon adopted as motifs in the visual world of Impressionism. Many photographers helped document the Seine bridges in Paris and the expanding network of railroads in France.

Augustin Hippolyte, called Auguste Collard: Pont de Grenelle, Paris, ca. 1875–76, Bibliothèque de l’École nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Marne-la-Vallée

The photographer Auguste Collard specialized in industrial architecture. This view of the Pont de Grenelle in Paris evinces a strikingly dynamic composition.

For painters and photographers, the new infrastructure of bridges and railroads was more than just an interesting motif. Modern transportation enabled creatives to enjoy unprecedented mobility and altered the landscape and its perception.

August Collard took this photograph from directly beneath the bridge: an unusual, striking perspective.

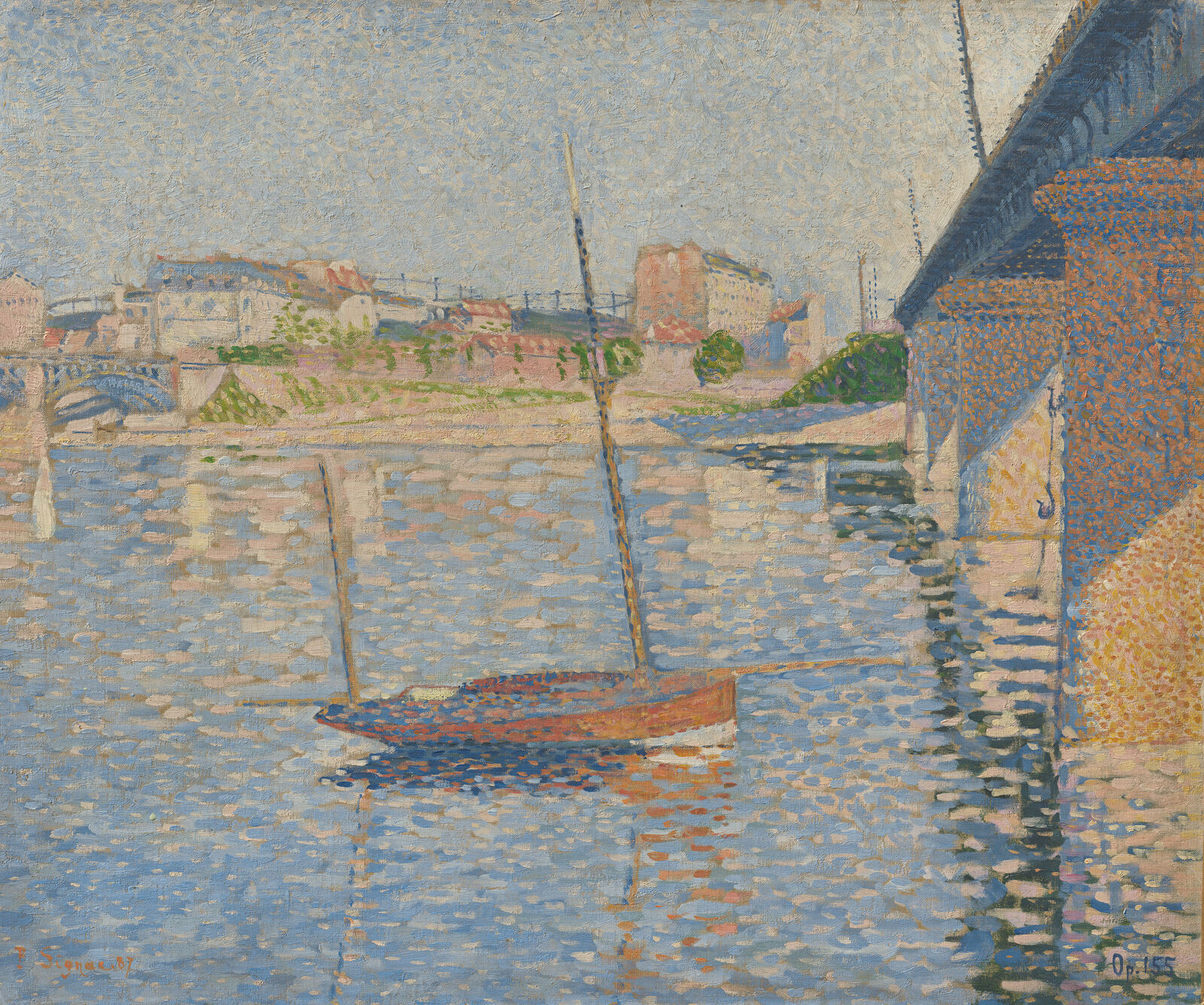

Modern bridge structures also appear in the works of Impressionist painters, such as Clipper by Paul Signac, created in 1887.

Auguste Collard documented all of the Seine bridges in Paris, including the Pont de Grenelle seen here.

Modern transportation, vehemently painted: the Fauve artist Maurice de Vlaminck echoed Impressionist motifs.

A picture like a walk in the woods: the finely differentiated play of light leads the eye into the depths in Georg Maria Eckert's Middle Ground Study - Rocky Path in the Forest.

Georg Maria Eckert: Middle Ground Study — Rocky Path in the Forest, Heidelberg, 1867–68, Münchner Stadtmuseum, Munich, Sammlung Fotografie

Shadow and Light

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Path in the Forest, 1874–1877, Hasso Plattner Collection

Like the Barbizon painters of the generation before him, Pierre-Auguste Renoir explored the world of the forest. His dissolution of form took Impressionism to a new level.

French landscape painting underwent profound changes in the nineteenth century. Increasingly, artists turned away from idealized images of nature.

Like the Barbizon painters before them, Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir embarked on lengthy painting excursions in the forest of Fontainebleau from 1862 on. They were followed by photographers with heavy, large-format cameras, wooden tripods, and portable darkrooms. These photographers, too, worked under the open sky, directly from the motif. The result was a new kind of landscape art. In the words of the painter Théodore Rousseau, the desire was to depict:

not trees where dryads dwell, but rather the (…) oaks of Fontainebleau, honest roadside elms, the simple birches (…) , and all this without any Greek temple (…)

Henri Le Secq: Forest Brook, ca. 1852–53, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

Due to the long exposure time, the babbling brook in Henri Le Secq’s photograph appears blurred, as if frozen. The rest of the image is sharply focused.

Many early photographers, such as Henri Le Secq and Gustave Le Gray, were trained as painters and thus had an eye for the subtle changes and compositional effects of light and shadow.

The photographer, even more than the painter, must search for and choose the correct vantage point, because unlike the painter he does not have the ability to add to or subtract from his picture. Regardless of the choice of location, the photographer must still choose the moment when the landscape is best lit and the day when nature is at its most beautiful.

The amateur photographer Eugène Cuvelier married the innkeeper’s daughter at the “Auberge Ganne” in Barbizon, a popular meeting place for artists—and stayed to explore the forest of Fontainebleau amid the changing seasons and atmospheres of light. He was friends with many of the painters who came as summer visitors, and some even purchased his photographs to use as models.

A path leading into depth—this classic motif from landscape painting occurs here in a photograph by Eugène Cuvelier.

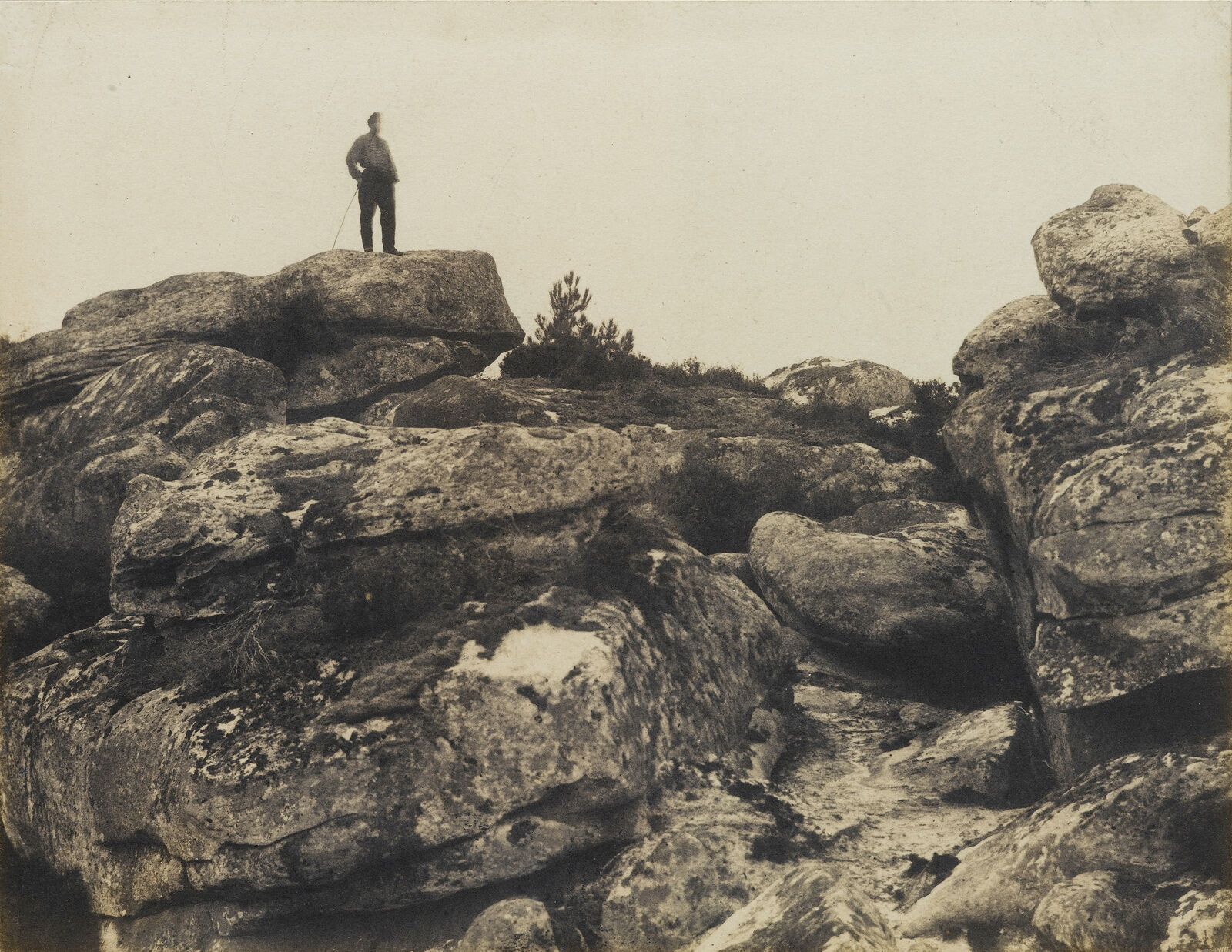

Even in those days, the strange rock formations in the forest of Fontainebleau were a tourist attraction.

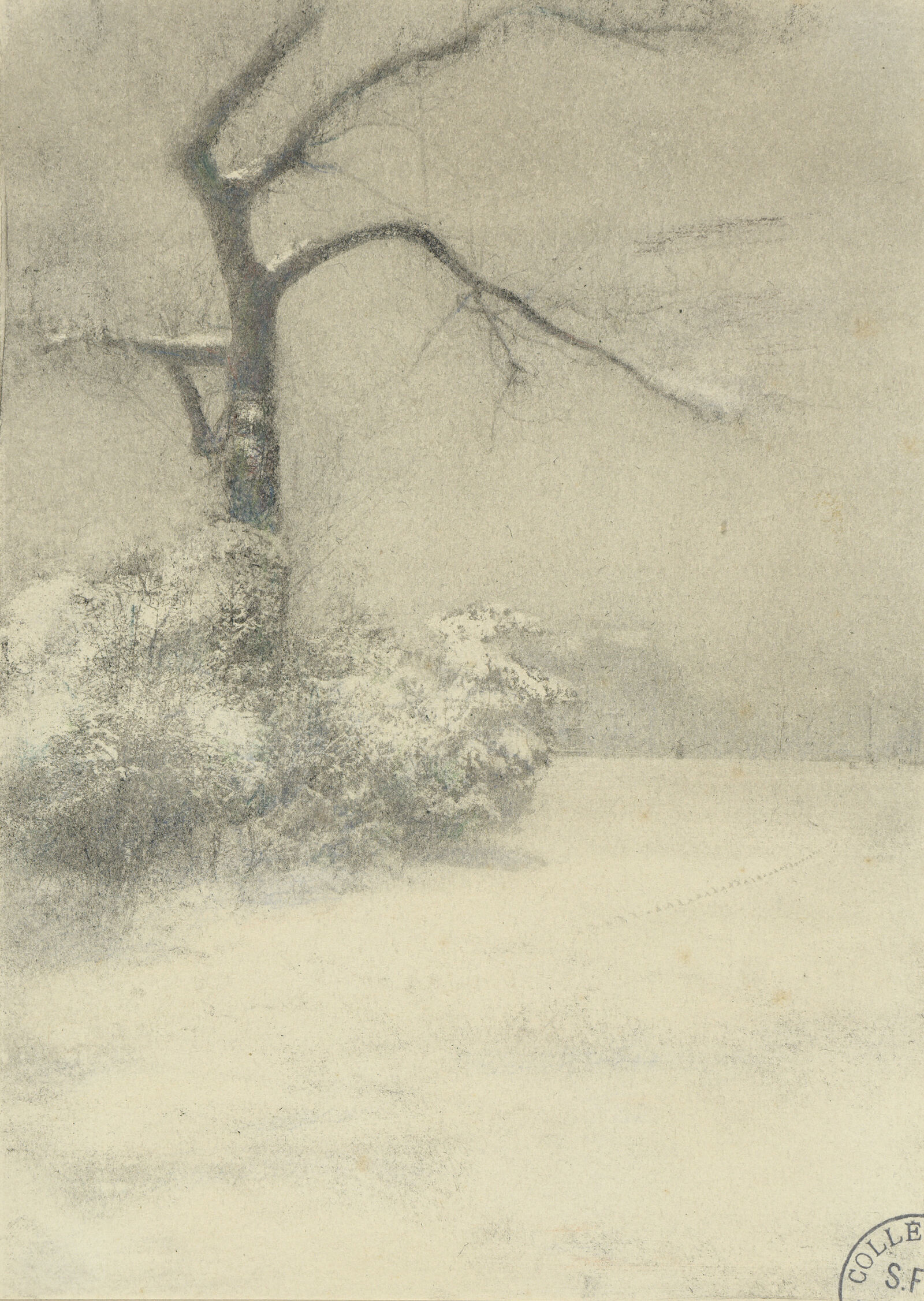

Eugène Cuvelier captured the familiar scenery of the forest of Fontainebleau, here transformed by snow.

The diffuse light in Constantin Puyo's photograph Two Women in a Field mimics effects of Impressionist painting.

Constant Puyo: Two Women in a Field, 1894–1926, Société française de photographie, Paris

Everyday Motifs

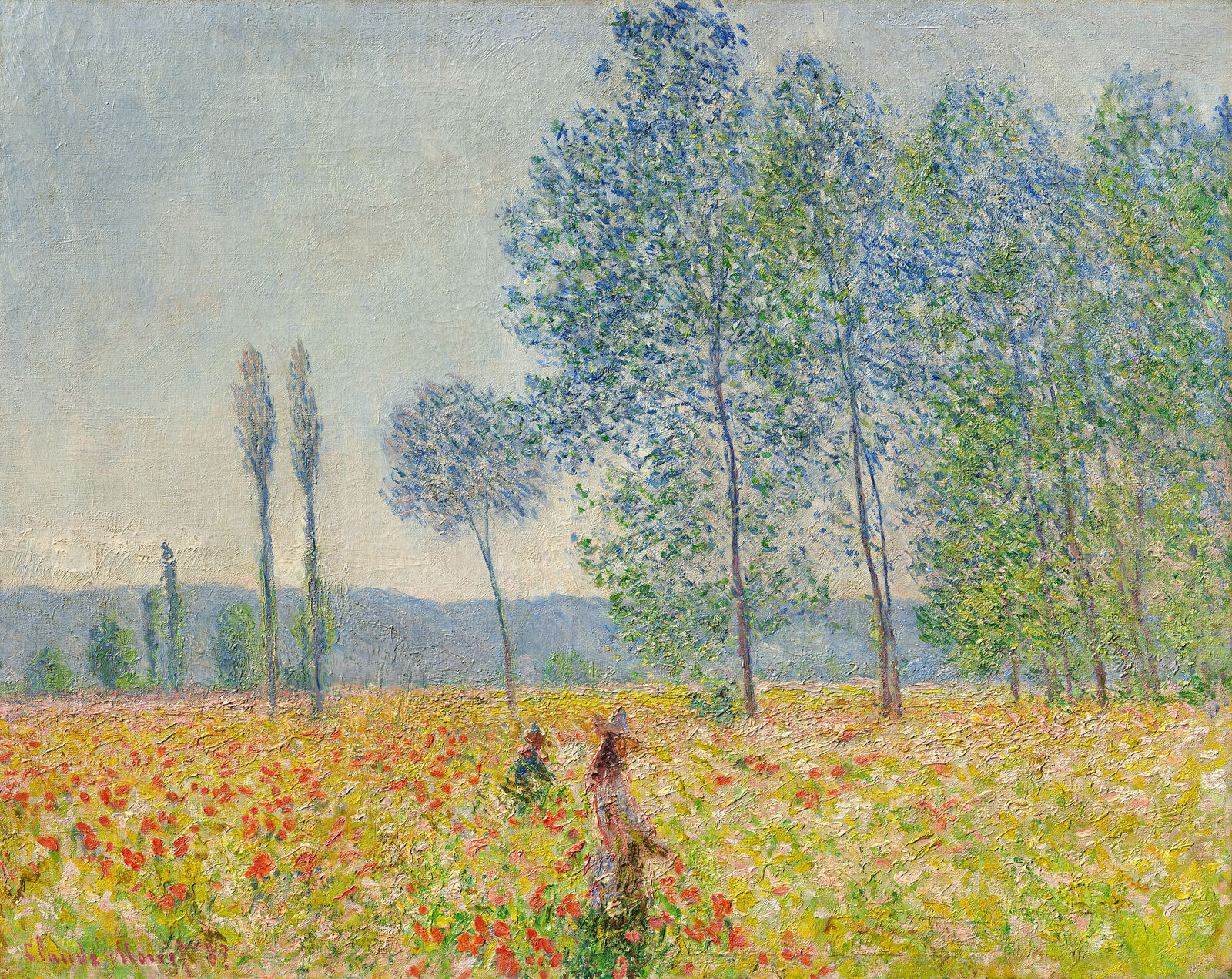

Claude Monet: The Flowered Meadow, 1887, Hasso Plattner Collection

In 1883, Claude Monet moved to Giverny, a village with fewer than 300 inhabitants about eighty kilometers northwest of Paris. There he found rural motifs in the environs of his own home.

Like the Impressionists around Claude Monet, photographers sought out ordinary landscapes, turning their gaze in an almost incidental manner to rivers, fields, and blooming meadows. Landscape photography ranged from regionalist documentation of agrarian life to artistically ambitious, “painterly” tableaus. The motifs reflect a reassessment of rural life as a refuge from the hustle and bustle of the city and rapidly expanding industrialization.

In the fields around their homes, the Impressionists painted pictures of humble motifs from the French countryside for audiences in Paris: crops in the field, rows of poplars, country lanes, and grainstacks. Photographers, too, turned their attention to the evidence of agricultural labor. Such images are not always documentary: Henry Peach Robinson, for example, arranged his models in carefully selected costumes like a theater director.

In the 1850s, British photographer William Sherlock produced images of rural life.

Life in the country with Camille Pissarro: two farm children kindle a brushwood fire. The everyday scene is idealized by the radiant winter light.

Not a snapshot, but a choreographed scene: the influential British photographer Henry Peach Robinson was a spokesman for fine art photography.

Stéphanie Breton: The Castle of Franqueville near Rouen, 1861, Société française de photographie, Paris

Stéphanie Breton, who lived in Rouen, was one of the few women photographers in the early days of the medium. Only a few of her works survive.

Streams with reflections of trees along their banks offered rich artistic possibilities for photographers and painters. Every change of location, every shift in the weather altered the play of reflective light. In contrast to mass-market commercial portrait photography, the genre of landscape played an important role in elevating photography to the status of art.

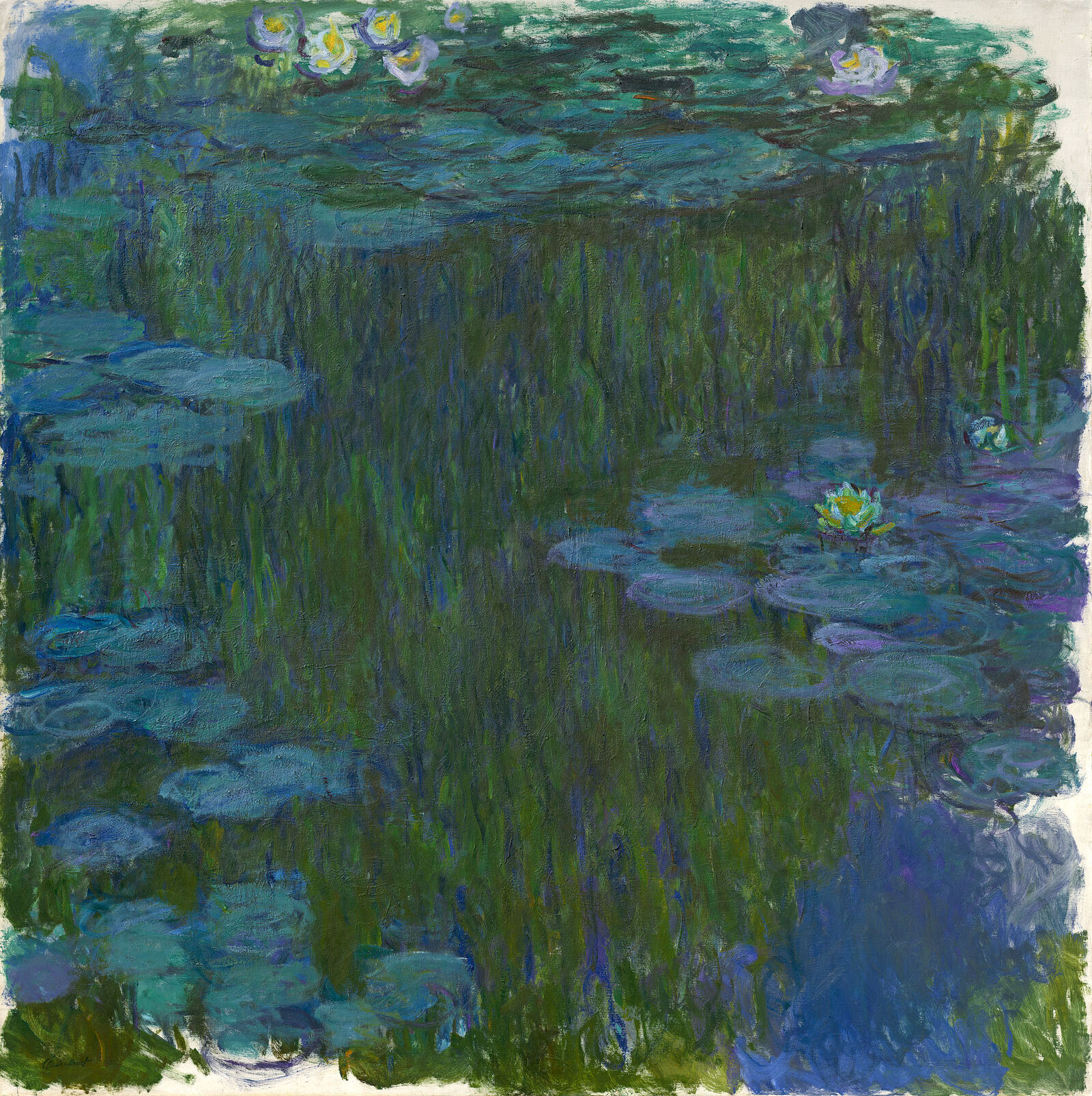

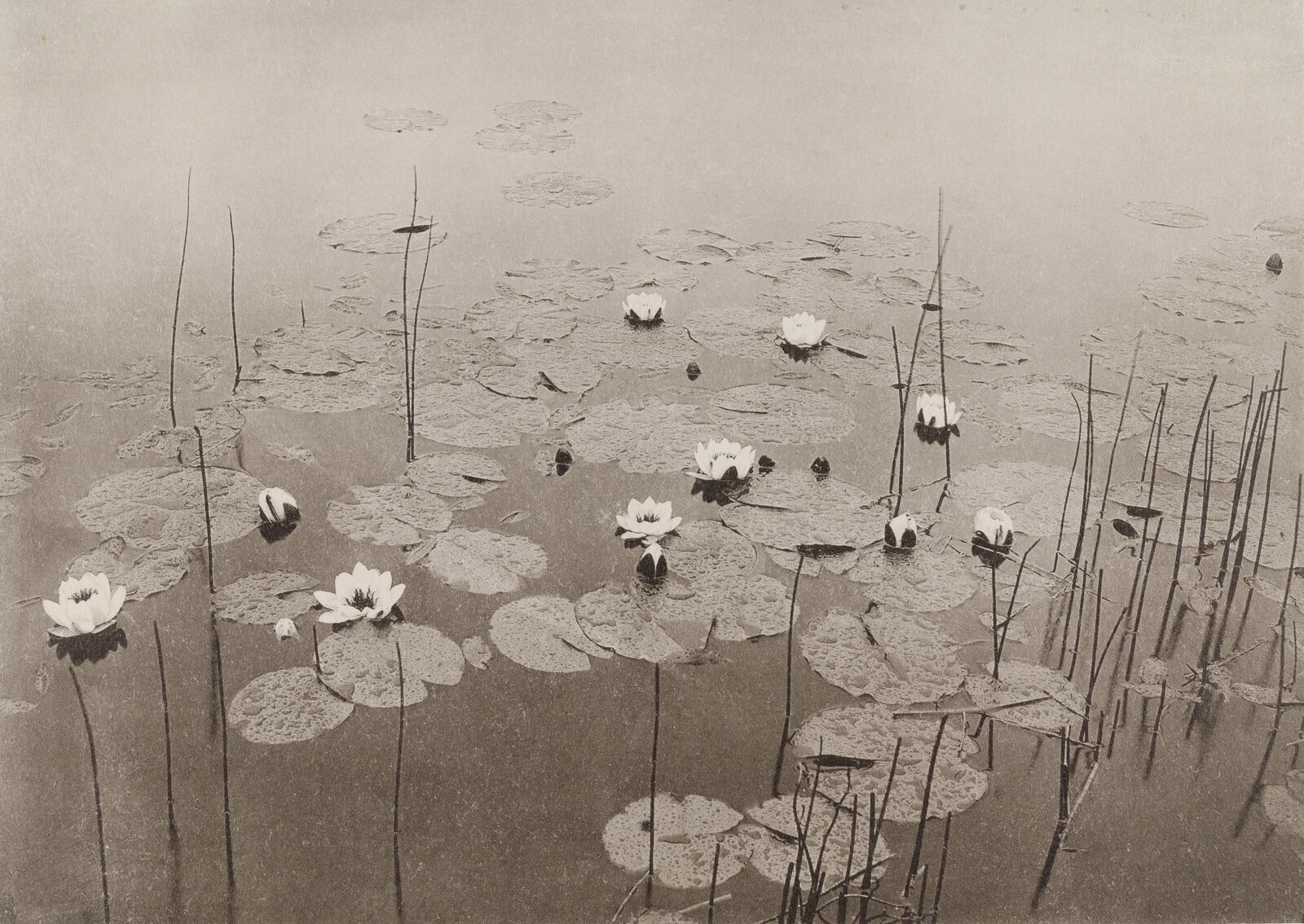

Many photographers tried to enhance the artistic quality of their landscape images by emulating painting in both style and motif — for example the water lily pictures of Claude Monet. In turn, the cropped compositions and snapshot-like character of photography changed the way painters perceived the world.

In the garden at Giverny, Monet installed his own water lily pond—a motif that would come to define his late oeuvre.

Like Monet, the American photographer Dwight A. Davis focused his gaze directly on the shimmering surface of the water, capturing it in the finest nuances of gray.

Monet’s late water lily paintings explore the interplay of light and reflections on the water.

Since color photography had not yet been invented in 1890, this anonymous photograph is colored by hand.

The water lily motifs popularized by Monet bear witness to the relationship of mutual influence and inspiration between the two media. In this process, the representation of fleeting, ephemeral impressions of nature becomes the hallmark of modernity.

For centuries, still life painters had sought to perfect the illusionistic rendering of objects and surfaces, an approach known as trompe-l’oeil — deceiving the eye. After the invention of photography, mechanically reproduced images took on a supporting function for many painters. An important point of intersection between the two media were the reference photos that increasingly began to replace traditional preliminary drawings. Many artists assembled archives of photographs with sharply focused, detailed images of plants, animals, or rock formations.

Charles Aubry: Still Life, ca. 1864, Musée d’Orsay, Dépôt du Mobilier national, Paris, © bpk / RMN - Grand Palais / Charles Aubry

Charles Aubry’s composition resembles a classical still life painting.

Charles Aubry had originally worked as a textile designer and spent over thirty years creating patterns for fabric and wallpaper production. In 1864, he opened a photo studio in Paris. His more than two hundred flower pictures, plant studies, and botanical still lifes captivate the eye with their finely nuanced chiaroscuro. They recall the paintings of the Old Masters.

Charles Aubry: Garden Asters, ca. 1864, Musée d’Orsay, Dépôt du Mobilier national, Paris, © bpk / RMN - Grand Palais / Charles Aubry

Charles Aubry sensitively captured the play of light on the delicate petals of his Garden Asters.

Gustave Caillebotte: Lilacs and Peonies in Two Vases, 1883, Hasso Plattner Collection

Precise observation of nature and free brushwork: the Impressionists also chose the traditional genre of still life.

The still life photographs of August Kotzsch, who worked in the environs of Dresden, seem amazingly modern. Their cool, detached approach emphasizes the sculptural concreteness of objects and anticipates the restrained aesthetic of the New Objectivity of the 1920s.

August Kotzsch: Cut Melon, ca. 1870, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Hungry for melon? The German photographer August Kotzsch found a market for his cool, objective photographs as far away as New York.

Claude Monet: Still Life with a Honeydew Melon, 1879, Hasso Plattner Collection

Monet shows a cut melon: his carefully arranged still life with fruit is remarkable for its voluptuous colors and forms.

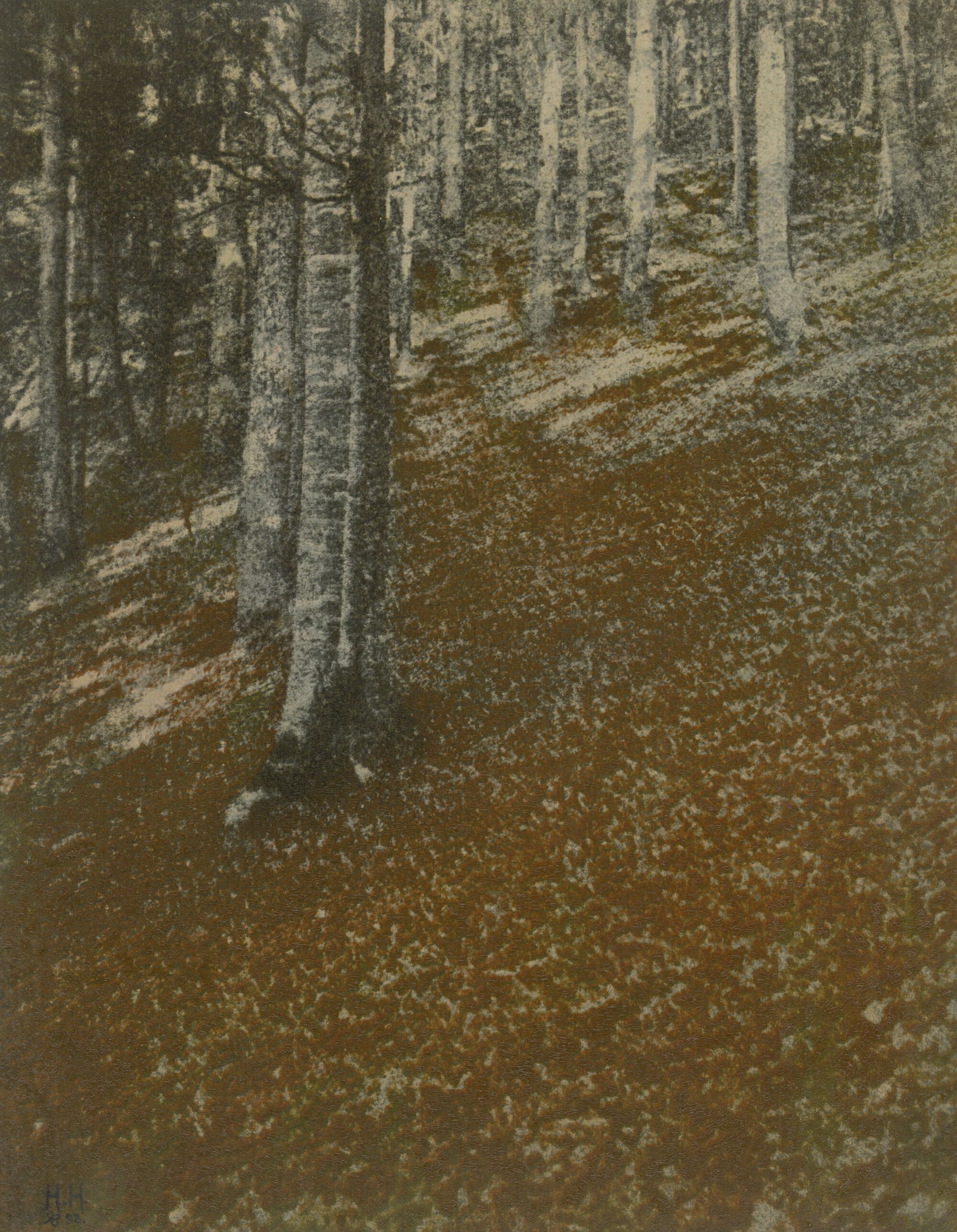

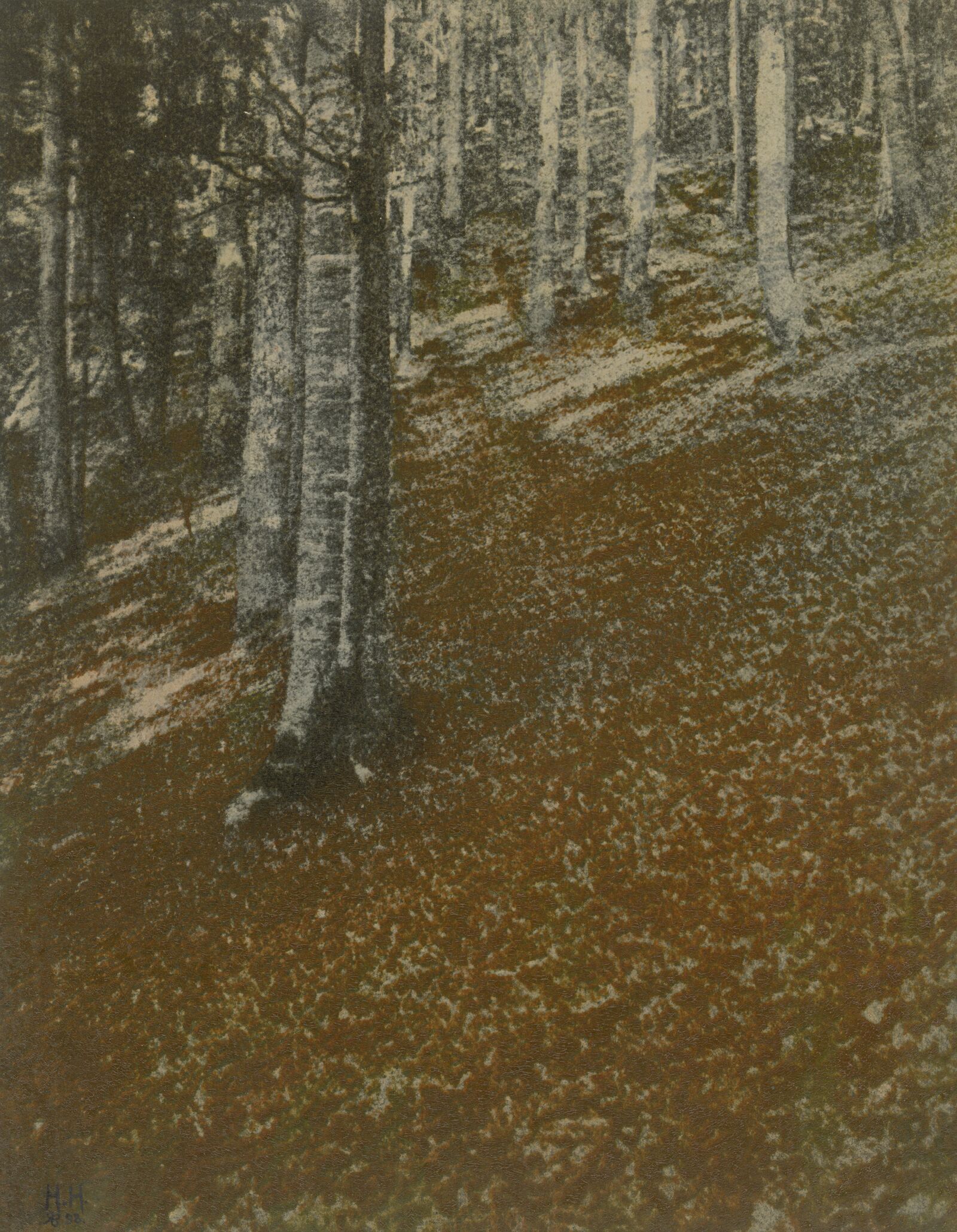

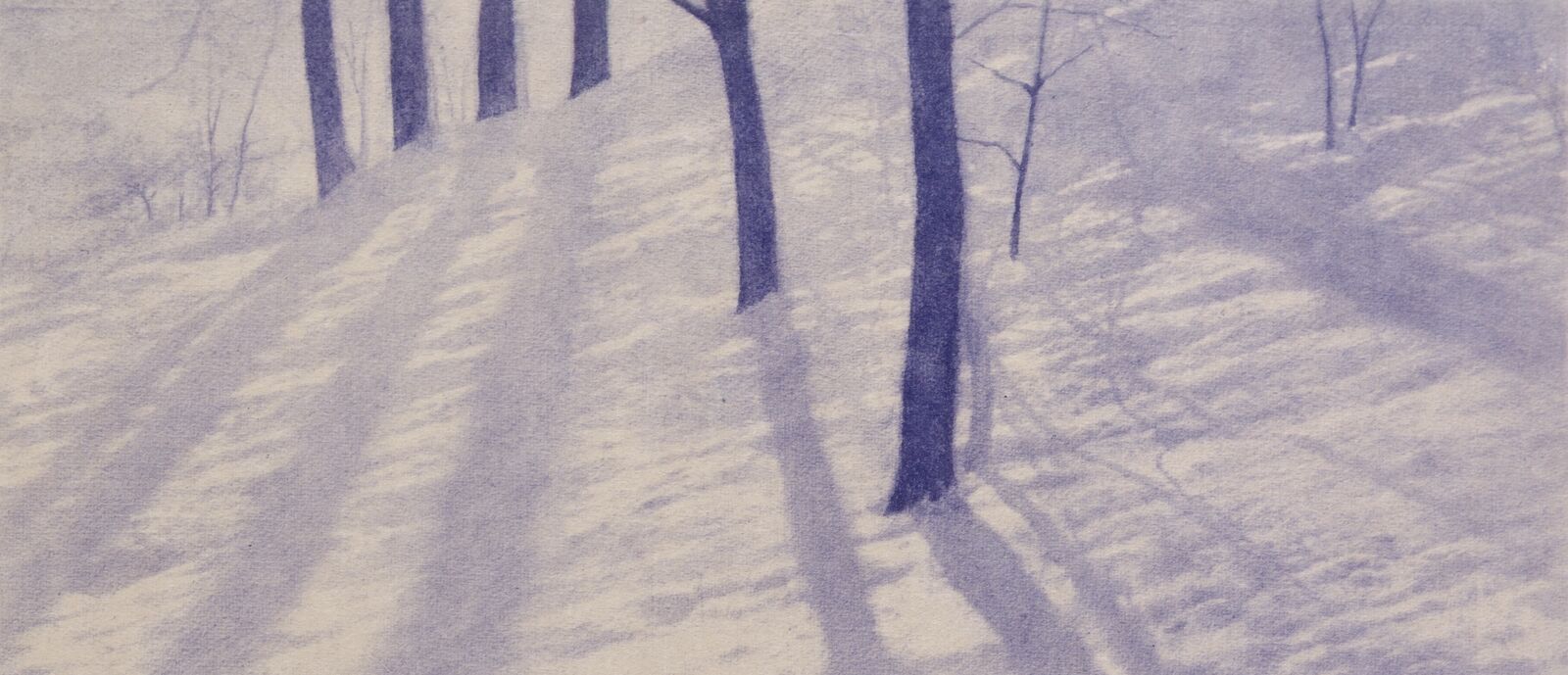

Lika a painting? The German photographer Hugo Henneberg achieved amazing effects through elaborate printing processes.

Hugo Henneberg: Beech Forest in Autumn, 1898, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

Painterly Photographs

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Shaded Path, 1872

In Renoir’s Shaded Path, colored daubs of paint evoke the dappled sunlight filtering through the leaves.

The artistic worth of photography was still contested as late as 1900. Many believed it could provide only a soulless reproduction of reality. Proponents of art photography vehemently advocated for the elevation of photography to a status equal to painting. This international movement, also known as pictorialism, emerged in the final decades of the nineteenth century and continued until the First World War.

Photography imitates everything and expresses nothing. It is blind in the world of spirit.

Fog was a favorite effect for many pictorialists of the period around 1900. Marcel Vanderkindere used it in a winter landscape in this photo from 1897.

The Belgian amateur photographer Édouard Hannon exhibited internationally. An engineer by profession, he financed his expensive hobby by working for a chemical company.

The Danish art photographer Carl Frederiksen used backlighting to achieve stunning effects.

Many pictorialists were passionate amateur photographers. They saw themselves as avant-garde artists and engaged the public through exhibitions and art theoretical publications. They intentionally sought out opportunities to show their photographs on equal footing with works of contemporary painting.

Claude Monet: Argenteuil, Late Afternoon, 1872, Hasso Plattner Collection

Monet was fascinated by the changing character of Argenteuil, a burgeoning industrial city. The smokestacks on the horizon bear witness to the rise of industrialization; in fine art photography, however, such motifs rarely occur.

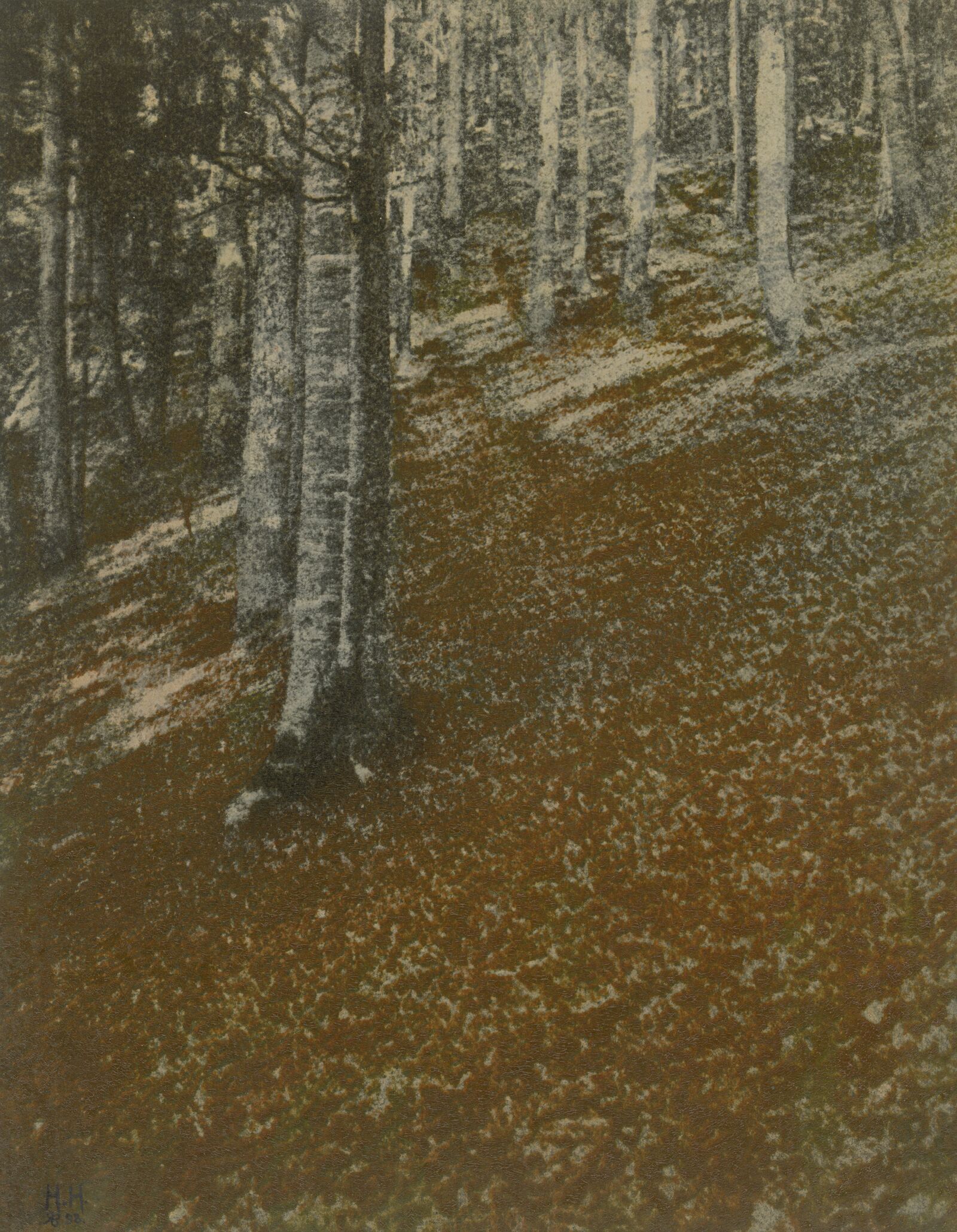

Robert Demachy: Banks of the Seine, ca. 1906, Société française de photographie, Paris

In this atmospheric work, the prominent pictorialist photographer Robert Demachy intentionally blurred the image.

The pictorialists also distanced themselves from the new phenomenon of mass photography, opting instead for technically ambitious fine art printing. For them, the negative was only the starting point for an elaborate artistic process. Its ultimate result was a positive image with the aura of a work of art: a unique, non-reproducible object.

Painterly blurring, diffused lighting, and soft contours characterize many works by art photographers. But they also experimented with colored tinting, using an elaborate gum bichromate process in which the image was printed multiple times in succession in variously colored pigments.

Heinrich Kühn was one of the most important pictorialists in German-speaking Europe.

In extensive series of works, Kühn experimented with the finest gradations of chiaroscuro and explored the effects of color.

A single, thoroughly considered picture, (…) as the final result of a systematic series of experiments (…) , is worth more than a dozen half-finished, technically barely adequate works.

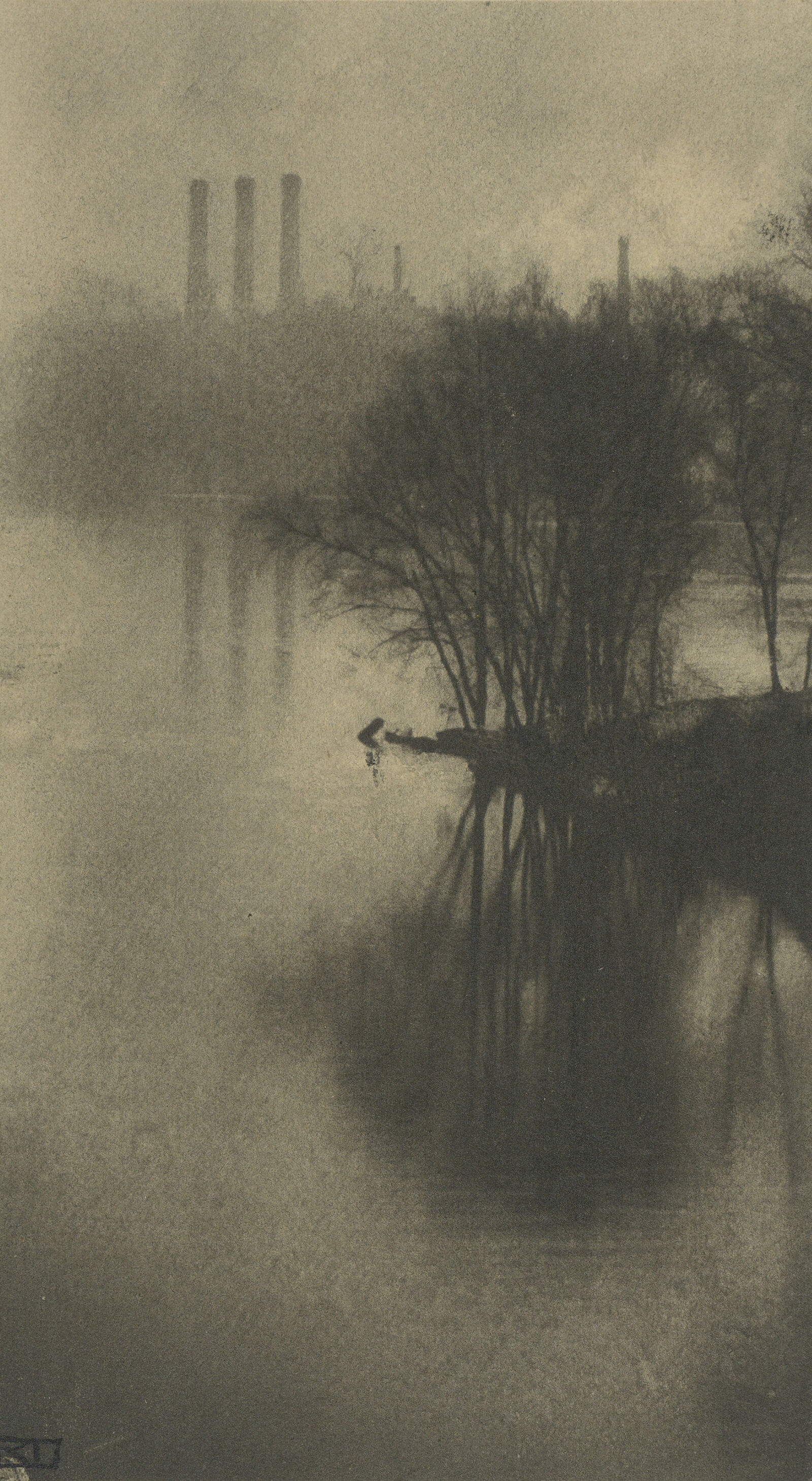

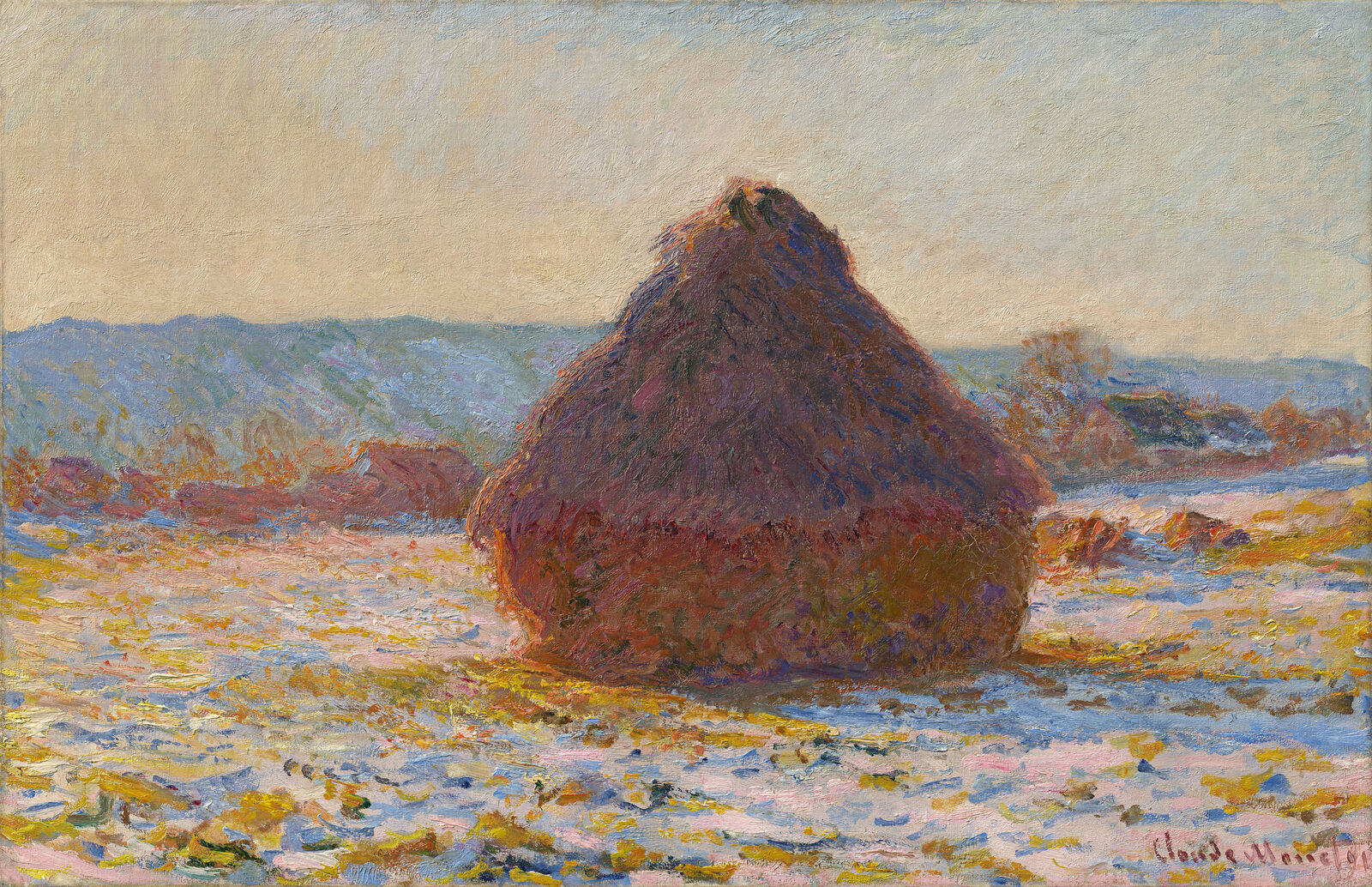

Winter landscapes had been present in European art since the seventeenth century. They were a motif that fascinated the Impressionists. For snow is never pure white: the frozen crystals reflect colored sunlight, and shadows glisten in nuances of blue.

Gustav Eduard Bernhard Trinks: Colored Shadows, 1897, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Sammlung Fotografie und neue Medien

Colored Shadows was the name the amateur photographer Trinks gave to this winter scene. The elongated shadows of trees in the low winter sun evoke an almost abstract impression.

In 1893, Claude Monet painted drifting floes of ice on the Seine in a symphony of pastel hues. Even bitter cold did not stop the Impressionists from painting in the open air.

Winter in Bazincourt: the intense glow of the setting sun gives a hint of warmth to Pissarro’s snowy landscape.

In Skaters at Giverny, Claude Monet applied rapid, sketchlike brushstrokes to the canvas in a rhythm that enlivens the quiet winter landscape.

Although the American photographer Rudolf Eickemeyer was self-taught, his works bespeak his artistic aspirations.

With bold compositions and otherworldly atmospheres, the pictorialists sought to compete with painting.

Antonin Personnaz: Sunrise with Snow, ca. 1907–14, Société française de photographie, Paris

Photography or painting? Personnaz takes up the motif of Monet's famous series of pictures of grainstacks.

Claude Monet: Grainstack in the Sunlight, Snow Effect, 1891, Hasso Plattner Collection

In both winter and summer, Monet painted the striking rural motif of grainstacks under varying conditions of light.

Heinrich Kühn often took his family as a model, as here. In this shot, the blur enhances the painterly effect.

Heinrich Kühn: Miss Mary and Lotte, 1907, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

The World in Color

It was a revolution in the development of photography: in 1907, the Lumière brothers marketed the first practicable process for color photography. Thanks to industrially prefabricated color screen plates, it was now possible to take automatically colored photographs. The glass plate negative was coated with tiny grains of pigmented starch, producing a granular effect in the finished photograph that recalled the dotted brushwork of Pointillism. The transparent color slides could be projected onto the wall in enlarged form, producing an almost magical effect.

Many art photographers rejected the autochrome since it offered little opportunity for the artist to intervene in the process of production or guide the pictorial effect through manual manipulation. The Austrian pictorialist Heinrich Kühn, however, enthusiastically embraced the autochrome process, creating carefully orchestrated compositions that betray the influence of Impressionism.

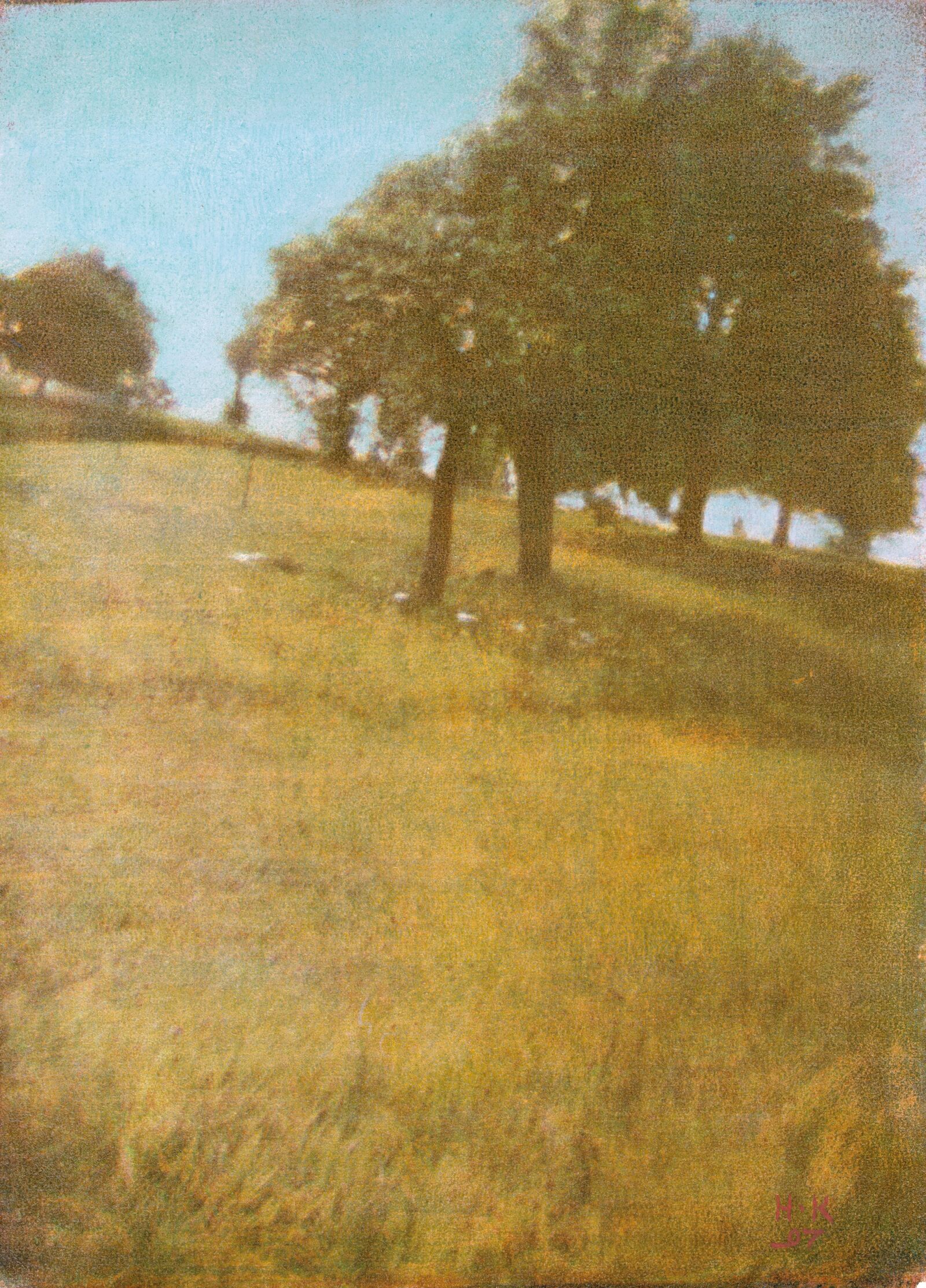

In this carefully calculated diagonal composition, the photographer Heinrich Kühn used his colorfully costumed children to set intentional color accents.

Passing clouds over a luxuriant green meadow: Heinrich Kühn translated a classic Impressionist motif into the new colored medium of autochrome.

Immersed in summer: Claude Monet used countless small brushstrokes to create a flickering atmosphere of color.

Frequent visits to painting galleries, but above all to the first Secession exhibition (…) were especially inspiring to me. The new expression of fine art had a decisive effect on my works.

An important proponent of artistic autochromes was Antonin Personnaz, a photographer who also made a name for himself as a collector of Impressionist painting. His river landscapes directly recall the pictorial strategies of Claude Monet and other Impressionists. Personnaz was a friend of the painter Armand Guillaumin.

Antonin Personnaz: Armand Guillaumin Painting “Bathers near Crozant”, ca. 1907, Société française de photographie, Paris

In 1907, Antonin Personnaz photographed the Impressionist painter Armand Guillaumin at work. The grainy quality of the autochrome enhances the impressionistic effect of this summery river landscape, while the figural composition alludes to a famous painting by the Pointillist Georges Seurat.

Women, too, took the camera in hand and experimented with the new techniques. The masterful autochromes of Louise Deglane recall Impressionist paintings in their visual strategies and choice of motifs. In 1914, she became one of the few women members of the Société française de photographie.

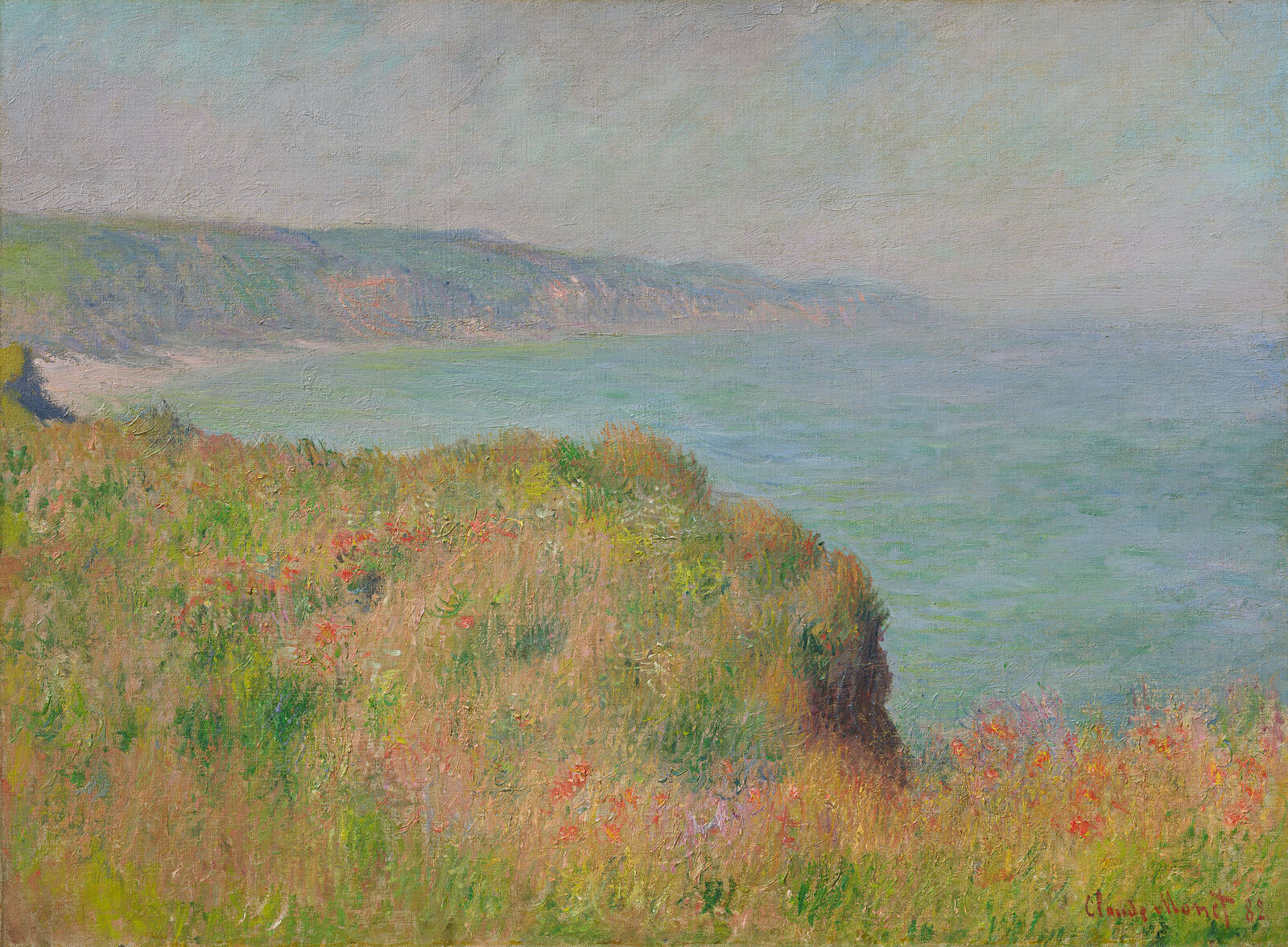

Claude Monet: Edge of the Cliff at Pourville, 1882, Hasso Plattner Collection

Monet explored the famous cliffs on the Normandy coast from a wide range of perspectives.

Louise Deglane: Beach with Boats (Étretat), 1907–36, Société française de photographie, Paris

The photographer Louise Deglane used soft, subtle colors in her image of the beach at Étretat, where Monet had painted decades before.

Claude Monet: The Garden at Vétheuil, 1881, Hasso Plattner Collection

Claude Monet painted his luxuriantly blooming gardens on countless occasions; here we see the garden at Vétheuil.

Louise Deglane: A Man in a Rose Garden, after 1907, Société française de photographie, Paris

Our gaze moves through a vine-covered trellis into a sunlit garden; the eye of the photographer Louise Deglane is guided by Impressionism.

The nineteenth century was marked by a productive rivalry between photography and painting. United by common themes such as light or the act of seeing itself, the two disciplines developed side by side in a mutual process of emancipation. For photography, the result was acceptance as a legitimate art form; painting, in turn, was inspired to redefine its own means of expression.

While avant-garde painters turned to currents such as Expressionism or Cubism, many works by pictorialist photographers were still shaped by Impressionism and Symbolism. Again and again, the tableaus of fine art photographers responded to the works of Impressionist painters, sometimes decades later.