The Shape of Freedom

The exhibition The Shape of Freedom. International Abstraction after 1945 focuses on the two most important currents of abstraction after World War II: Abstract Expressionism in the United States and Art Informel in Western Europe. It is the first show to explore the transatlantic dialogue between these two artistic movements from the mid-1940s to the end of the Cold War.

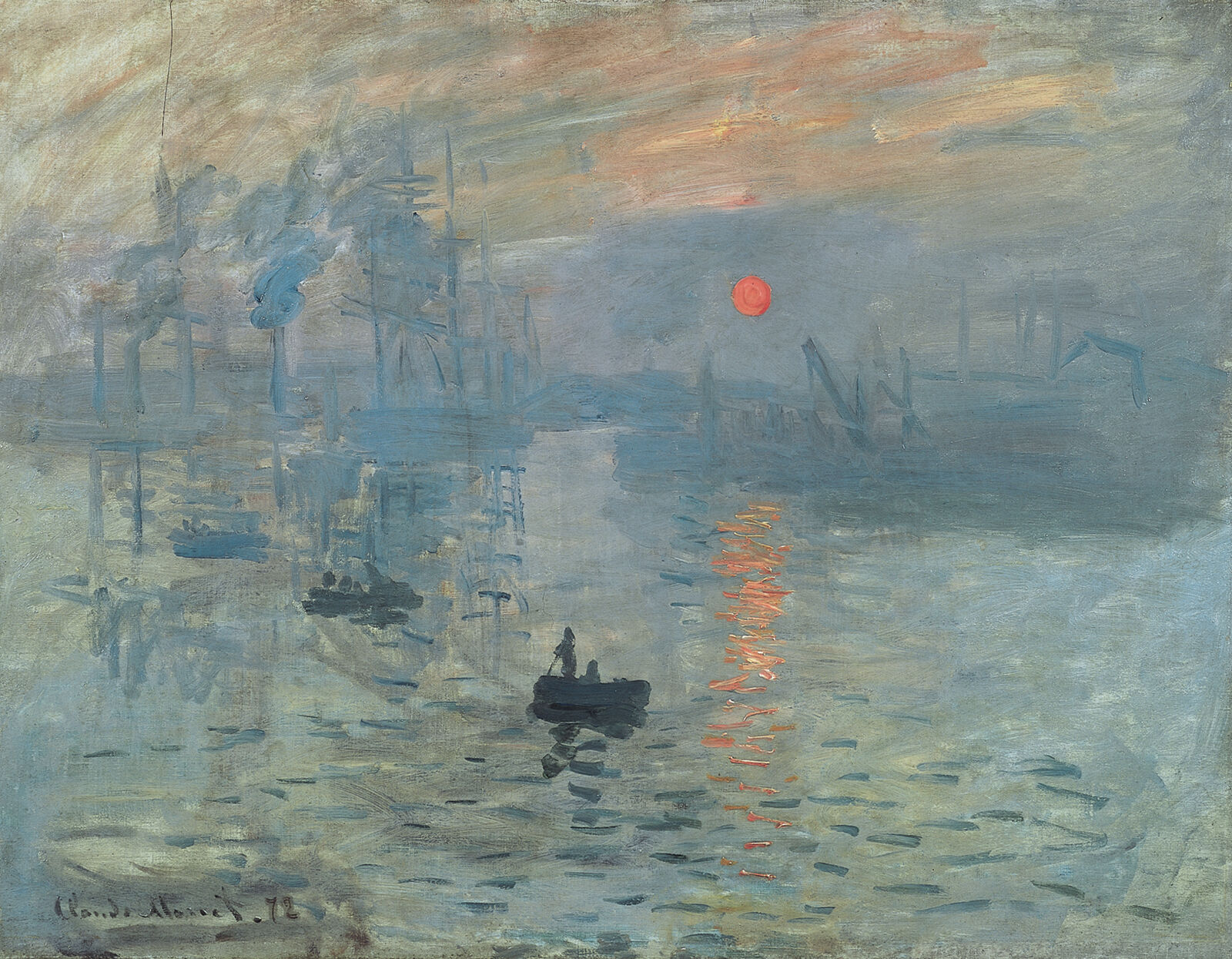

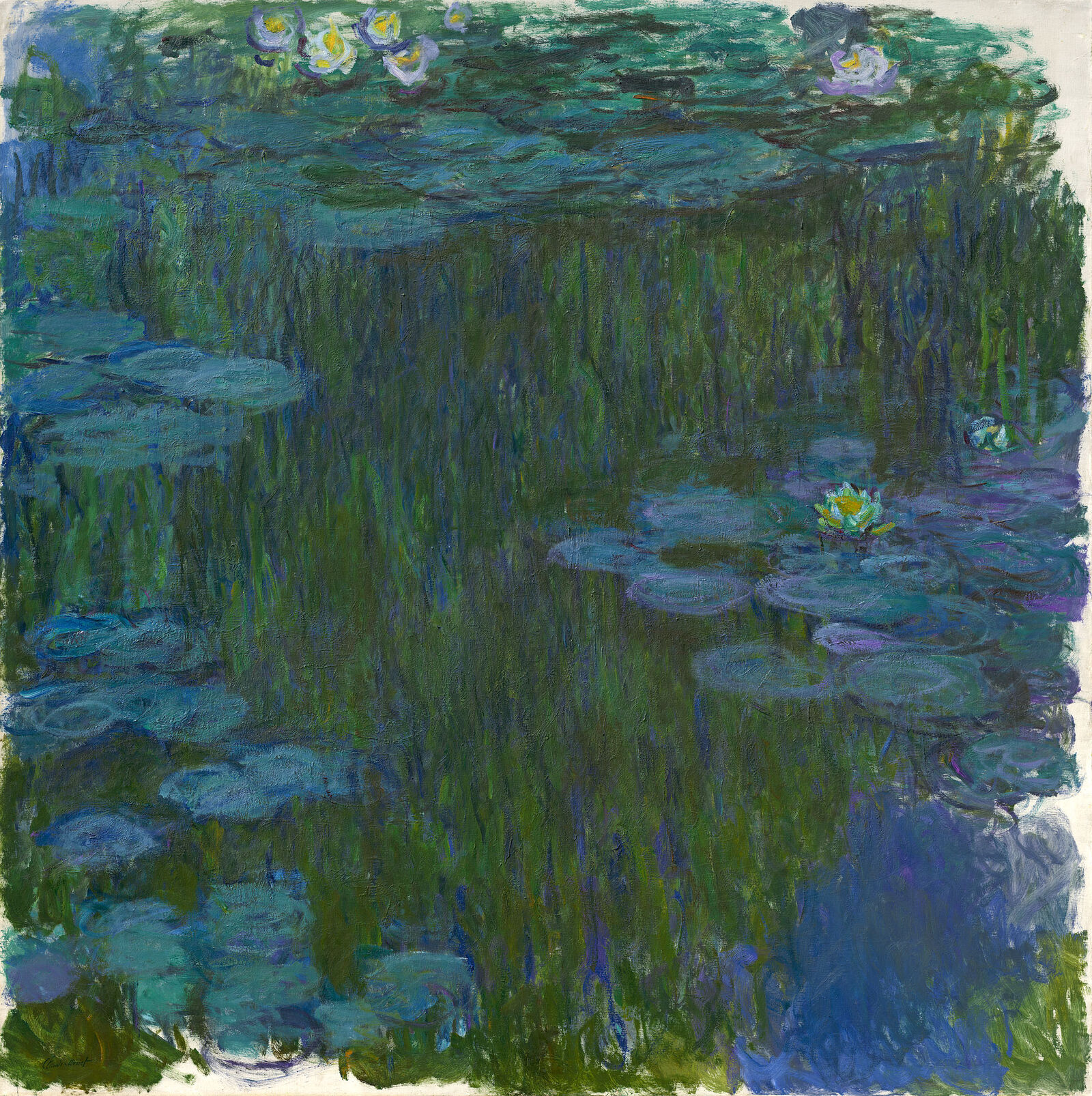

The exhibition brings together 97 works by over 50 artists, including many icons of postwar abstraction. The show takes its point of departure from a number of important paintings in the Hasso Plattner Collection, whose holdings also include key works of French Impressionism. Artists like Joan Mitchell, Sam Francis, and Norman Bluhm were inspired by Impressionist landscape painting. The nearly abstract water lily paintings of Claude Monet, in particular, were viewed by many as anticipating twentieth-century artistic developments.

The role of the artist, of course, has always been that of image-maker. Different times require different images. (...) To my mind certain so-called abstraction is not abstraction at all. On the contrary, it is the realism of our time.

The exhibition presents iconic painters like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Lee Krasner, Barnett Newman, Georges Mathieu, and Ernst Wilhelm Nay alongside lesser-known artists whose contributions to the development of abstract painting after 1945 have been largely ignored: the many discoveries to be made in the show include works by Jean Degottex, Perle Fine, Simon Hantaï, Manolo Millares, Judit Reigl, Janet Sobel, Hedda Sterne, and Theodoros Stamos.

The Barberini Prolog to the exhibition ...

... offers an in-depth view of how Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel emerged as the leading avant-garde movements after World War II, influencing and inspiring one another in transatlantic exchange.

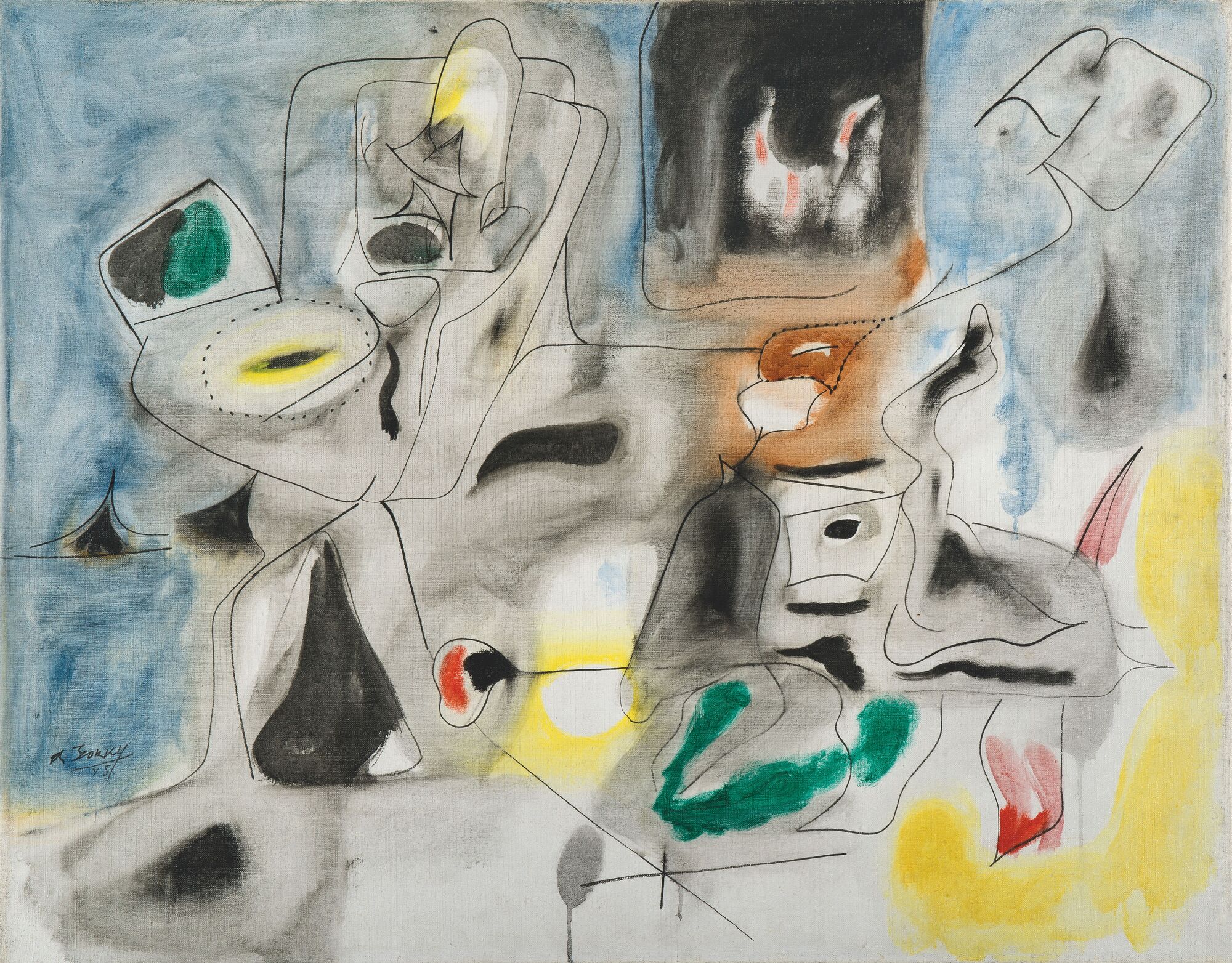

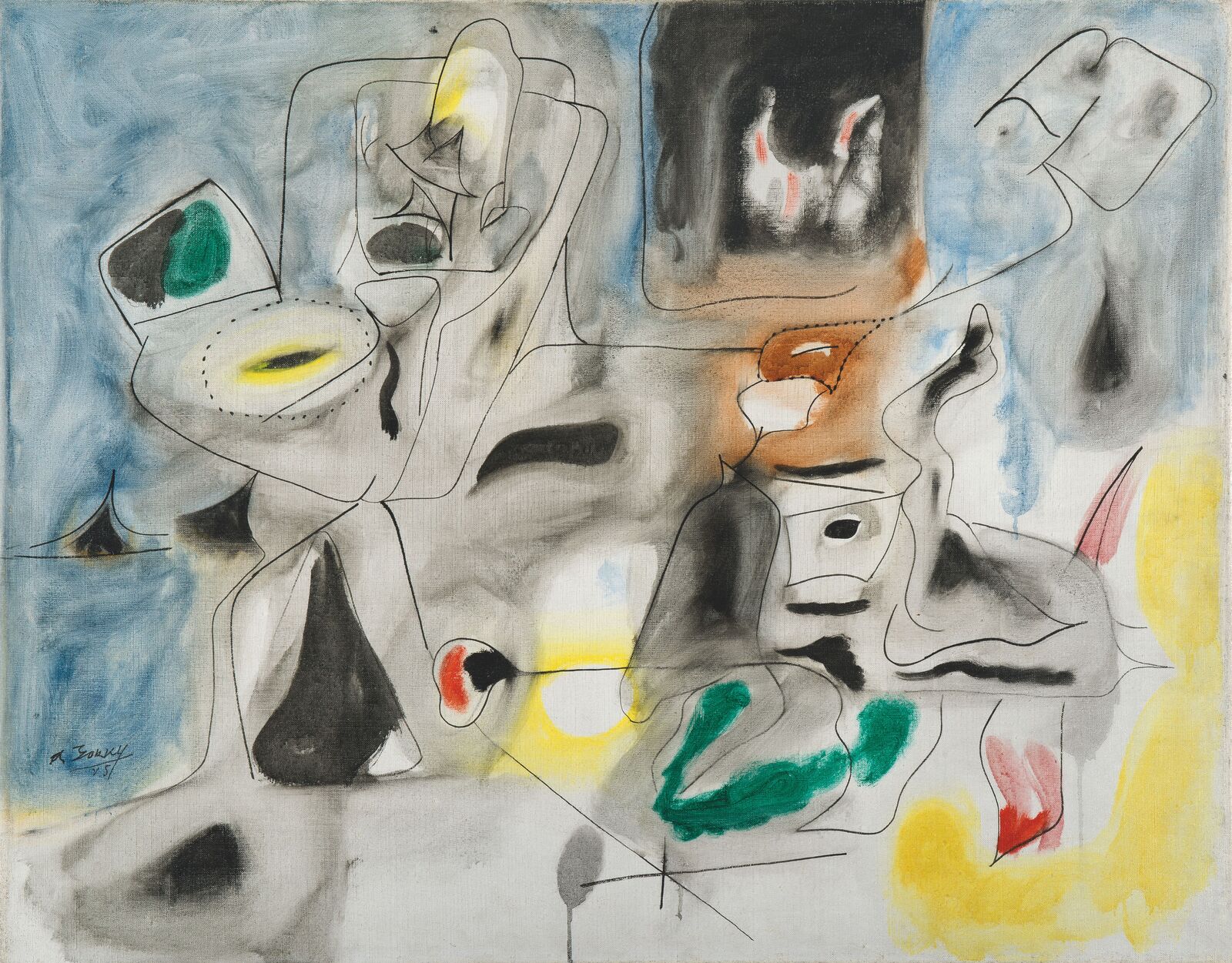

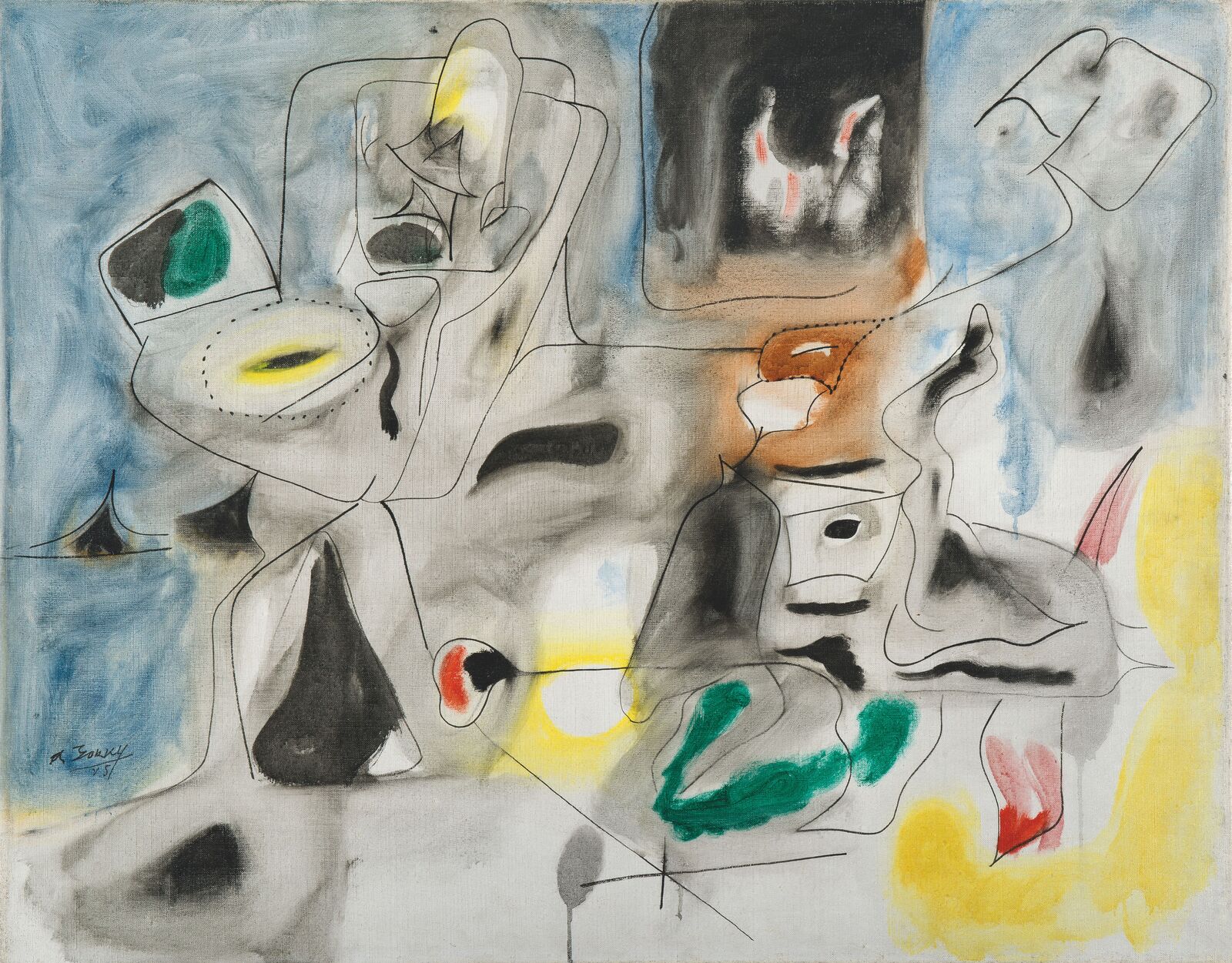

Arshile Gorky was born in Armenia and fled to the United States to escape the Armenian genocide. His poetic, expressive paintings stand at the threshold between Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. Gorky was one of the central figures of the New York art scene in the 1940s.

Arshile Gorky: Good Hope Road II. Pastoral, 1945, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

The decade of the 1940s marked a turning point in the development of modern painting. World War II, the horrors of the Holocaust, and the shock of Hiroshima and Nagasaki prompted an existential search for meaning on the part of many artists. For them, abstraction meant first and foremost the rejection of the human figure, which had hitherto been the primary motif in Western painting.

Paris, the international center of modern painting from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1940s, increasingly yielded its preeminence to New York. Many European avant-garde artists fled to the United States to escape war and persecution. There, in galleries like Peggy Guggenheim’s “Art of this Century,” they exchanged ideas with young American painters. For artists like Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock, the Europeans were important role models.

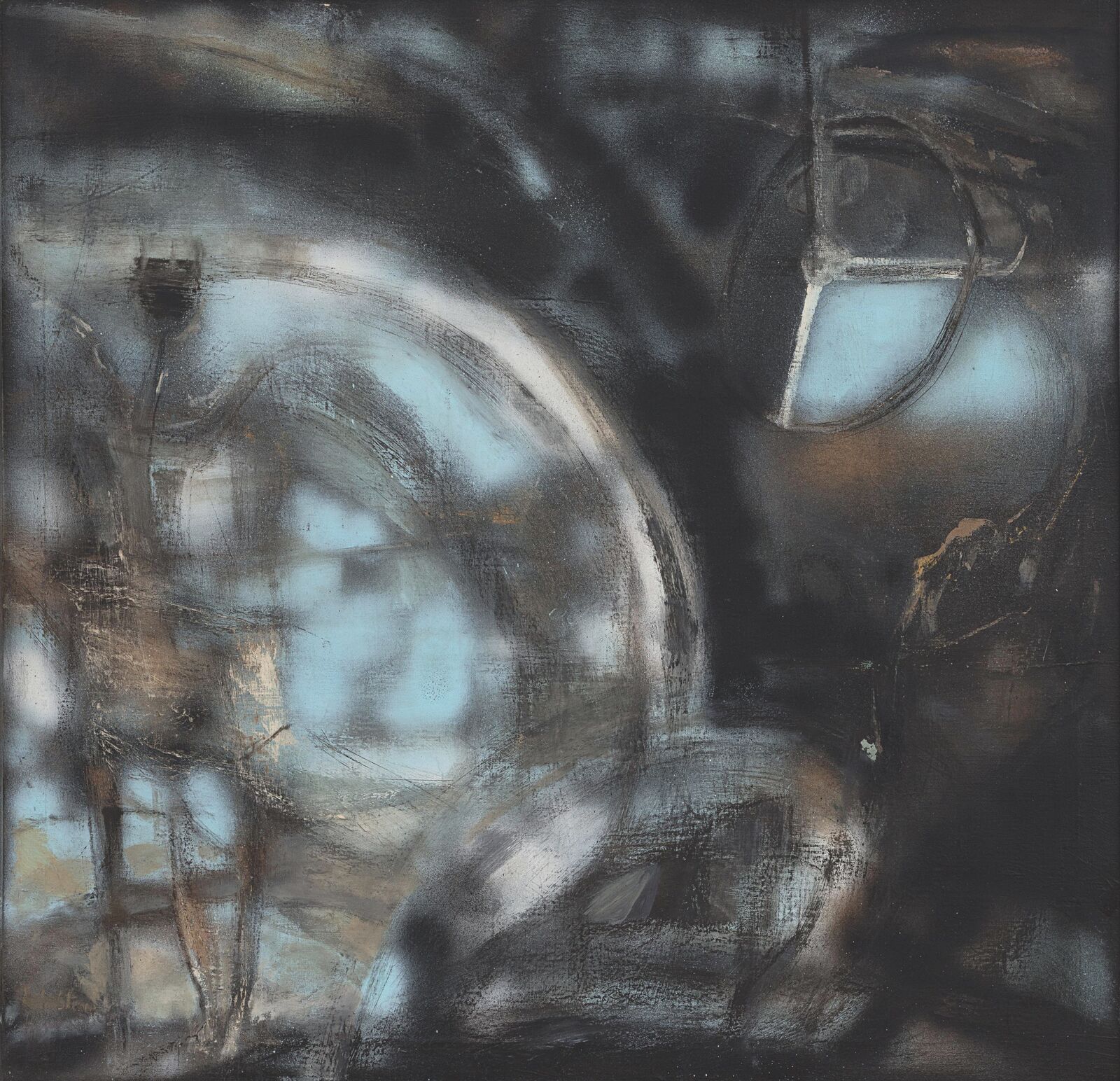

The “New York School” developed as an avant-garde collective of exiled European artists together with their American counterparts. In the 1950s and 60s, they established themselves as pioneers of Abstract Expressionism. Their number included Hedda Sterne, one of the few women painters who was able to assert herself in the male-dominated art world of the 1950s.

Hedda Sterne: N.Y. #7, ca. 1955, ASOM Collection

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

The Jewish painter Hedda Sterne was born in Bucharest in 1910. In 1941, she fled to America and received American citizenship in 1944. Her series N.Y. expresses her fascination with her adopted homeland.

Although the artists of this new movement did not embrace a uniform style or share a common manifesto, they were united in their conviction that painting should not seek to render external reality. Instead, they saw their task as the instinctive expression of emotion. For them, the canvas was a stage on which creative energies should be allowed to unfold freely and spontaneously. This spirit is also reflected in a 1943 statement by several of the avant-garde artists active in New York:

To us art is an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by those willing to take the risks. (...) It is our function as artists to make the spectator see the world our way — not his way.

The title of Mary Abbott’s painting Imrie alludes to her friendship with the economist Imrie de Vegh. The expressive brushwork of her Action Painting reveals the influence of Willem de Kooning. Along with Perle Fine and Joan Mitchell, Mary Abbott was one of the few women accepted into the “8th Street Club,” a discussion group dominated by the Abstract Expressionists.

Mary Abbott: Imrie, 1952, Collection of Thomas McCormick and Janis Kanter, Chicago, Illinois

Photograph courtesy McCormick Gallery, Chicago

Even before the outbreak of World War II, the Surrealists in Paris had developed techniques for integrating chance elements into the composition of their pictures. They used semiautomatic processes to develop a direct, dynamic approach to painting, working rapidly and without preliminary planning. At the same time, this process was also intended to release the creative powers of the unconscious. In their so-called Action Painting, the Abstract Expressionists drew inspiration from the works of their European colleagues.

At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act. (...) What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event. The painter no longer approached his easel with an image in his mind; he went up to it with material in his hand to do something to that other piece of material in front of him. The image would be the result of an encounter.

Willem de Kooning: Untitled X, 1976, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Willem de Kooning is considered one of the leading figures of American Action Painting. Like many artists of the New York School, he maintained a studio in Downtown Manhattan.

Most of the Abstract Expressionists did not make preliminary drawings. Instead, Action Painting foregrounded the spontaneous, painterly gesture — an artistic means of self-assertion. The works typically show powerful marks and energetic brushwork.

The impulsive application of color is also characteristic of Hans Hofmann’s First Sprouting. Born in Bavaria in 1880, Hofmann emigrated to the United States in the early 1930s and became one of the most important forerunners of Abstract Expressionism.

As a teacher at art schools in New York and Provincetown, he exposed his students — including women artists like Perle Fine, Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krasner, and Joan Mitchell — to German and French avant-garde painting.

Hans Hofmann: First Sprouting, 1960/61, Private Collection

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Hofmann’s influence on an entire generation of artists, however, extended beyond his activity as a teacher: the term “Abstract Expressionism” was first coined in a review of his art in 1946. Shortly thereafter, it became widespread as a general term for American postwar abstraction.

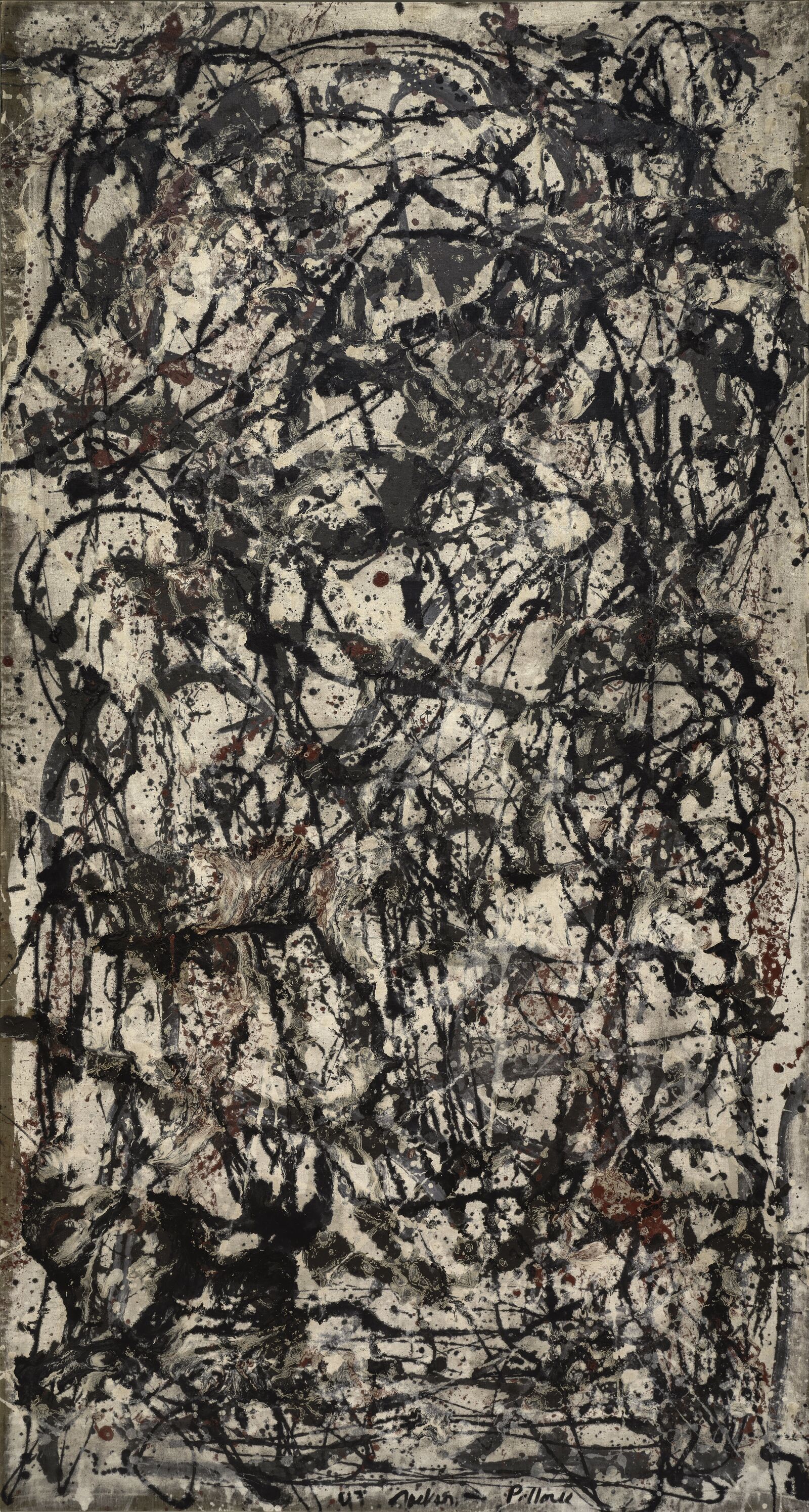

Jackson Pollock: Composition Nr. 16, 1948, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

No center, no foreground, no above or below — with “all-over” effects, every part of the painting is equally developed. The image often seems like an arbitrary section of a composition that can be imagined as continuing beyond the edges of the canvas.

The Abstract Expressionists sought to redefine the relationship between paint layer and ground. They avoided spatial illusionism and emphasized the presence of the canvas as a two-dimensional surface.

The most famous examples of the “all-over” effect are the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock. The artist laid his canvas on the studio floor and covered it with densely tangled strands of color, dripping, spattering, and pouring the paint onto the surface in rhythmic, dance-like movements.

Jackson Pollock: Enchanted Forest, 1947, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venedig (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York)

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Image: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York (Photo: David Heald)

Today, Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings are considered the epitome of American Action Painting.

Their often monumental size, reminiscent of fresco painting, would become a trademark of Abstract Expressionism. Critics frequently described the works as imposing, epic, or heroic, emphasizing the overwhelming sensory power of their spatial effect. With their focus on the free play of color and form, American artists of the postwar era radicalized a tendency that had already begun to emerge in French landscape painting of the late nineteenth century.

Beginning in the early 1950s, this revolutionary new technique also influenced the development of European abstraction. Without resorting to geometric structure, the works are often marked by a decorative character.

Janet Sobel: Illusion of Solidity, ca. 1945, ASOM Collection

© Estate of Janet Sobel

Ukrainian-born painter Janet Sobel was one of the many women pioneers of American abstraction promoted by Peggy Guggenheim in the 1940s. It is also highly likely that her works influenced the development of Pollock’s drip paintings.

Lee Krasner, the companion and later wife of Jackson Pollock, was also a leading figure in Abstract Expressionism, although she was ignored by critics and art historians for decades. The couple’s influence on each other’s work was not limited to mutual inspiration: in her painting Bald Eagle, Lee Krasner used discarded fragments from her husband’s drip paintings.

Lee Krasner: Bald Eagle, 1955, ASOM Collection

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Lee Krasner was long known primarily as the wife of Jackson Pollock, for whose work she tirelessly advocated. Not until the 1970s did her own art begin to be recognized for its profound influence on Abstract Expressionism.

When one starts using the unconscious as a source to take off, it doesn’t mean that it’s an unconscious painting because the conscious¬ness is there. The artist is there. You’re aware. The point at which you stop or pick up or make your next move is a conscious move.

This work is a characteristic example of the Color Field Painting of Mark Rothko. Paintings like this one from his most famous series show soft-edged, monochromatic blocks of color positioned above one another. They seem to float within a colored space, at times even blurring into each other.

Mark Rothko: Untitled (Blue, Yellow, Green on Red), 1954, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Digital image: Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala

Color Field Painting developed alongside Action Painting as a second current of Abstract Expressionism. The works typically feature rhythmic arrangements of large forms, painted in only a few colors.

Color Field Painting often involved monumental formats and the negation of spatial depth. Many of the works are intended to be viewed at close range, inviting viewers to contemplatively immerse themselves in the pictorial field.

I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on — and the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions. (...) The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.

One of the pioneers of Color Field Painting was Clyfford Still. While artists like Mark Rothko applied the paint in thin layers, Still produced impasto, relief-like surfaces, using the palette knife to create textures.

Clyfford Still: PH-847, 1953, Private Collection. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth (Photo: Alex Delfanne)

After 1947, Clyfford Still no longer gave his works associative titles. With his monumental formats, he sought to create visual fields of energy that would inspire viewers to search for meaning beyond objective references.

Adolph Gottlieb likewise connected his painting to an existential search for meaning. In a text written by Gottlieb together with Mark Rothko in 1943, the two artists state: “We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.” In his painting, Gottlieb pursued the quest for a universal visual language, thereby tending toward a reduction that manifests itself in his Burst series.

Adolph Gottlieb: Burst 1973, 1973, Collection of the Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, New York

© Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation/Licensed by ARS, New York / VG-Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

In his Burst series, begun in 1957, Adolph Gottlieb repeatedly varied a single pictorial scheme. In works like Burst 1973, the glowing red disk evokes the life-giving energy of the sun, while the reduced brushwork on largely monochromatic fields alludes to East Asian ink paintings.

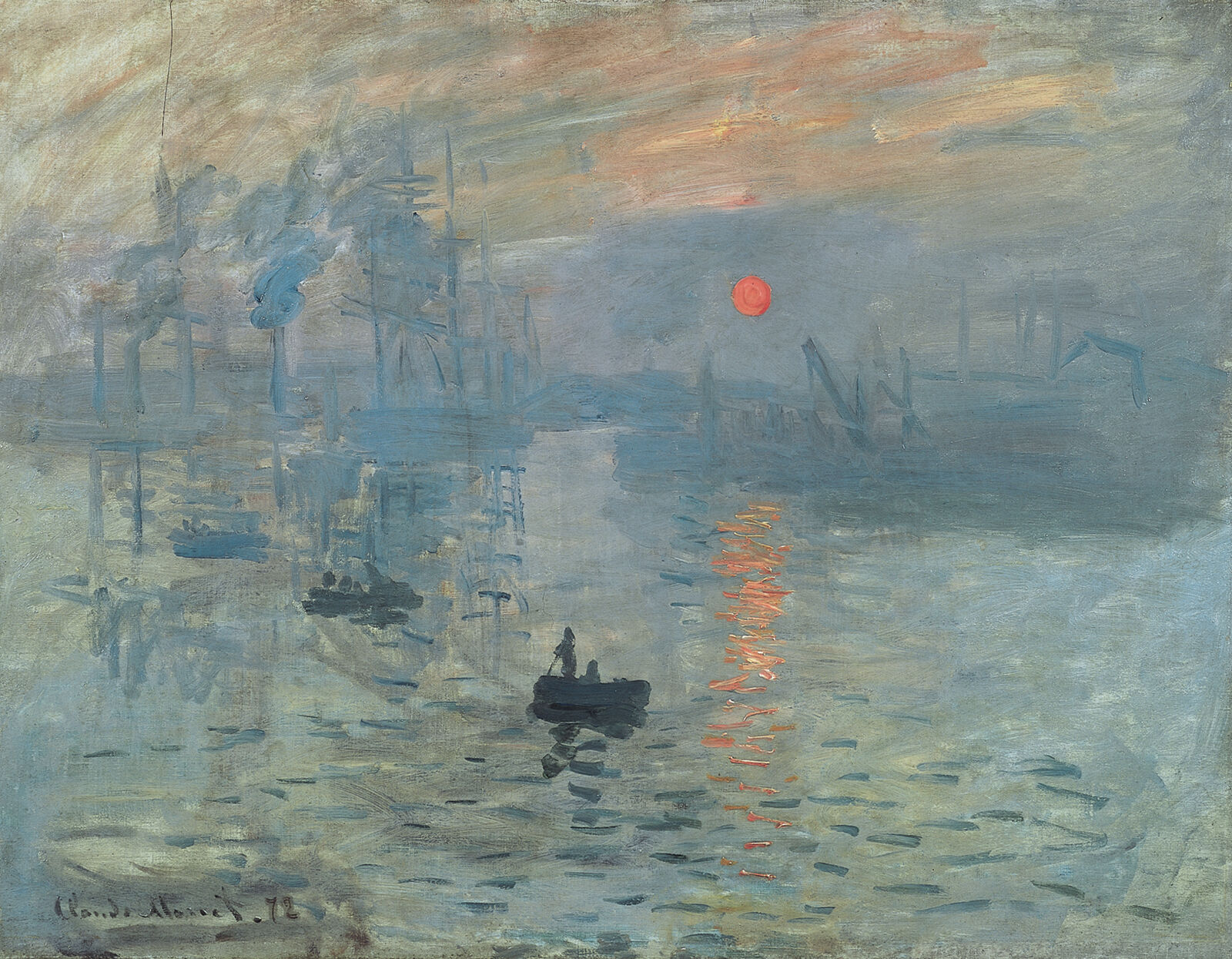

Claude Monet: Impression, Sunrise, 1872, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

With her staining process, Helen Frankenthaler developed an approach that combined elements of Action Painting and Color Field Painting. She poured strongly thinned paint onto the picture plane, allowing it to soak into the fabric as a form-creating “stain.” Since the paint did not simply cover the canvas, but completely dyed the fibers, the traditional separation of paint layer and support was eliminated.

By lifting and moving the support, Frankenthaler allowed the paint to flow freely across the surface. She often gave representational, associative titles to her nonobjective works. Motifs of landscape and nature served as key reference points for Frankenthaler’s monumental abstractions.

Helen Frankenthaler: Beach Scene, 1961, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photograph Rob McKeever, courtesy Gagosian

Both real and imagined impressions of nature formed the point of departure for Helen Frankenthaler’s Beach Scene.

Any successful picture — an abstract work or a landscape — has a place and rightness and an ability to last and grow. It is not merely a matter of painting a tree, but of making a picture that works.

Helen Frankenthaler’s fellow artist Morris Louis also used the staining technique for his Color Field Paintings. He adopted this approach after being impressed by it during a visit to Frankenthaler’s studio in 1953. He poured paint onto the canvas in a carefully orchestrated sequence of colors, creating a rhythmic pattern of glowing veils.

Morris Louis: Saf Heh, 1959, ASOM Collection

© All Rights Reserved. Maryland Institute College of Art/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

The painting Saf Heh belongs to a group of compositions in which Morris Louis allowed the paint to flow in two directions. Like most of his paintings, this one, too, was titled only after his death. “Saf” is the last, and “Heh” the fifth letter of the Hebrew alphabet.

A sunlit landscape, rippling water, flickering light: Joan Mitchell’s works were inspired by nature, and in particular by the countryside around the French village of Vétheuil, where she settled permanently in 1969. Claude Monet had also lived and worked there for a number of years.

Joan Mitchell: River II, 1986, ASOM Collection

© Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York

With the emancipation of color from form, the American postwar avant-garde embraced a tendency that had already characterized French landscape painting in the late nineteenth century.

Claude Monet: Water Lilies, 1914–1917, Hasso Plattner Collection

Artists and critics were fascinated by Monet’s seeming anticipation of the very thing for which they, too, were striving: a new relationship between the viewer and the work, established through scale, flatness, and compositional strategy.

Sam Francis, who had encountered Abstract Expressionism through the work of Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still during his time as a student in the late 1940s, also studied the nature scenes of Claude Monet. From 1950 on, Francis spent a number of years in Paris, where he also contributed to the exchange between Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel. With his American origin and close connection to the French art scene, he was seen early on as a link between Paris and New York on both sides of the Atlantic.

Sam Francis: My Shell Angel, 1986, Hasso Plattner Collection

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Lutz Bertram

Sam Francis’s large-scale abstractions show a luminous play of pulsating color fields, spatters, and splotches. Their calligraphic character bears witness to East Asian influences.

Another Abstract Expressionist painter who was associated with the Paris art scene early on was Joan Mitchell. Unlike Francis, Mitchell had initially built her international reputation in New York, where she participated in the pioneering 9th Street Art Exhibition in May and June of 1951. Along with Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Robert Motherwell, she belonged to the avant-garde clique around the artists’ group known as the 8th Street Club in Lower Manhattan.

From the mid-1950s on, Mitchell regularly spent extended periods of time in France and settled there permanently at the end of the decade. Through Sam Francis, she made the acquaintance of numerous artists and critics from the milieu of Art Informel, including Georges Mathieu, Judit Reigl, and Michel Tapié as well as Simon Hantaï, with whom she became close friends.

Joan Mitchell: Faded Air I, 1985, Private Collection

© Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York

In 1958, both Joan Mitchell and Sam Francis were represented in the London exhibition Abstract Impressionism. The works of both artists are viewed as the artistic legacy of Impressionism.

In 1968, Mitchell moved to the Seine village of Vétheuil, where she lived near the former home of Claude Monet. Many of her brilliantly colored Action Paintings are reminiscent of Monet’s sun-drenched landscapes.

I paint from landscapes of the memory I carry with me. I prefer to leave nature to itself. I do not intend to improve it. I could never mirror it. I love most of all what it leaves inside me.

For over 25 years, Jean-Paul Riopelle was romantically involved with Joan Mitchell, whom he met through their mutual friend Sam Francis. Like Mitchell, he too viewed his works as abstracted landscapes and was fascinated by the use of color in French Impressionism.

Jean-Paul Riopelle: Untitled, 1954, ASOM Collection

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

The 1940s were a period of profound change in European painting. Many artists had been involved in the war or had suffered under fascist dictatorships. As with American art, figurative styles receded into the background.

In Paris and other Western European cities, the painting of Art Informel developed parallel to Abstract Expressionism in the United States. Its open, “formless” pictorial structure was based on an improvisational approach to brushwork, surface texture, and material.

In many works, scratches, holes, or gouges evoke the feeling of bodily wounds. In a postwar world traumatized by violence and fascist terror, gestural painting was also an expression of the existential search for meaning.

The rise of Art Informel led to the reemergence of the École de Paris, with artists Wols and Jean Dubuffet playing a crucial role.

Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze): Composition Champigny, ca. 1951, MKM Museum Küppersmühle für moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Sammlung Ströher

The self-taught artist Wols painted not only with a brush, but also with brush handles, forks, knives, fingers, and paint tubes. As a pioneer of Art Informel, his work was defined by improvisation and a completely free handling of colors and forms. Like the American Action Painters, Wols embraced the spontaneous artistic gesture.

In America, Art Informel was soon perceived as a European pendant to Abstract Expressionism and was greeted with intense interest. In October 1950, the group exhibition Young Painters in the US and France opened at the Sidney Janis Gallery, with seven painters from each country paired in visual dialogues — Rothko with Nicolas de Staël, for example, or Hedda Sterne with Maria Helena Vieira da Silva.

Three years later, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum mounted the exhibition Younger European Painters, in which Art Informel was represented with works by Alberto Burri, Hans Hartung, Georges Mathieu, and Jean-Paul Riopelle. In 1955, the Museum of Modern Art followed suit with The New Decade: 22 European Painters and Sculptors, showing artists such as Karel Appel, Alberto Burri, Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Soulages, and Fritz Winter.

Jean Dubuffet: The Archer, 1953, Fondation Gandur pour l‘Art, Genève

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Bild: Fondation Gandur pour l‘Art, Genève. Photographer: Sandra Pointet

Many people can’t imagine painting as the expression of a human being who thinks differently. If they could understand ‘the Chinese’ of our pictures, they would read in them the sadness of every day and sense their liberation and renunciation. (...) They don’t realize that the act of painting is the sum total of our hopes. They don’t understand that we must make extreme, unknown revelations through the distinct lines of our paintings.

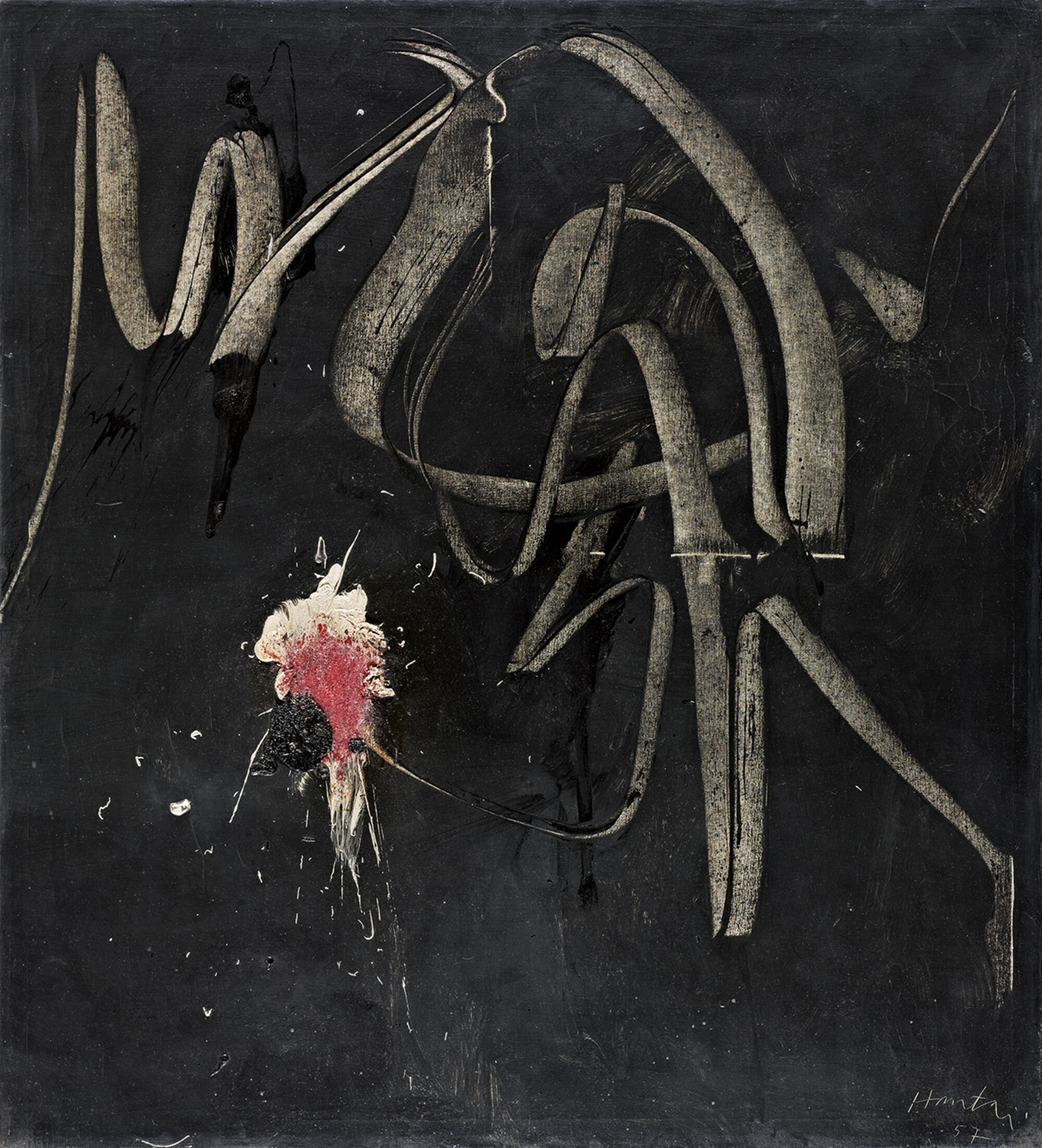

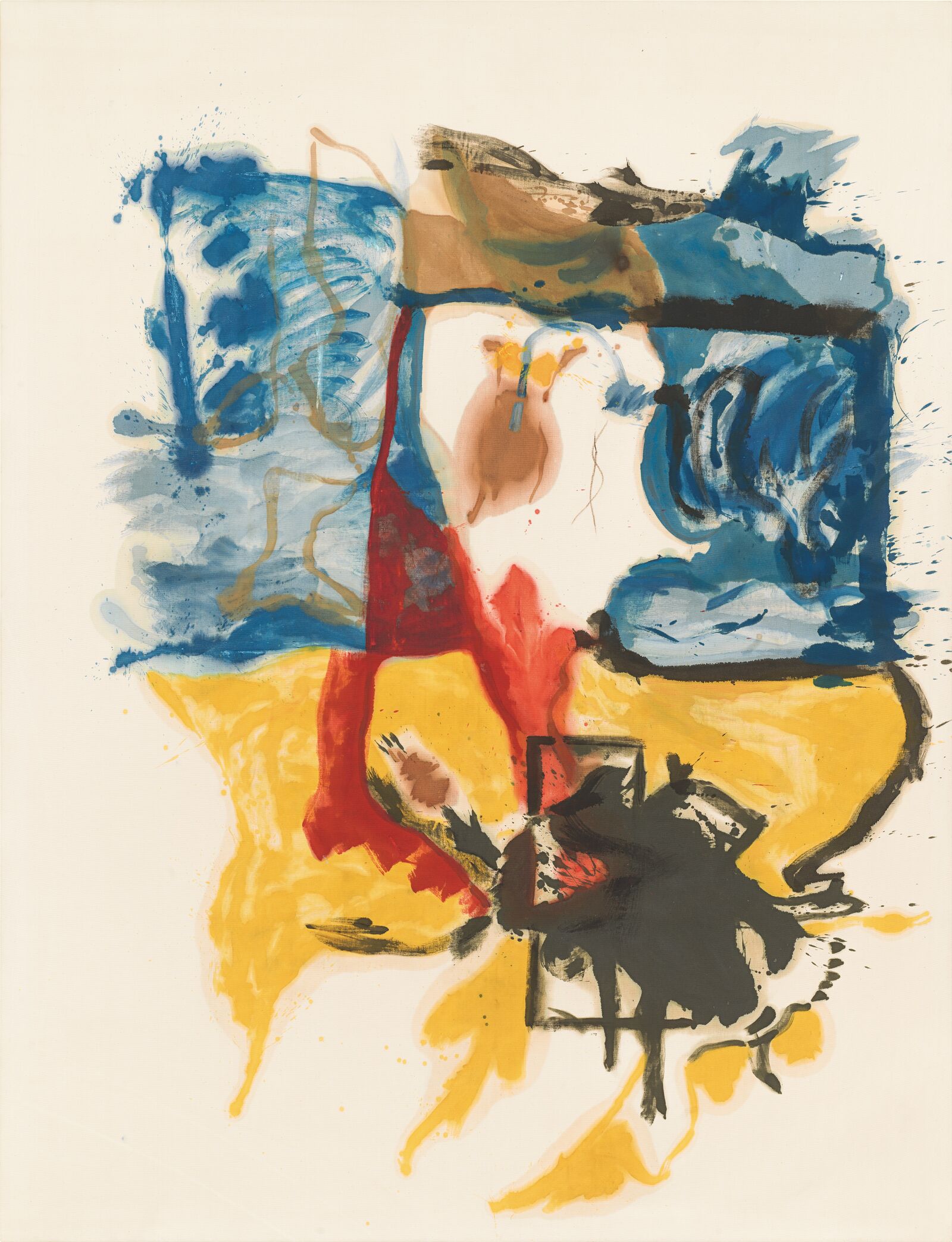

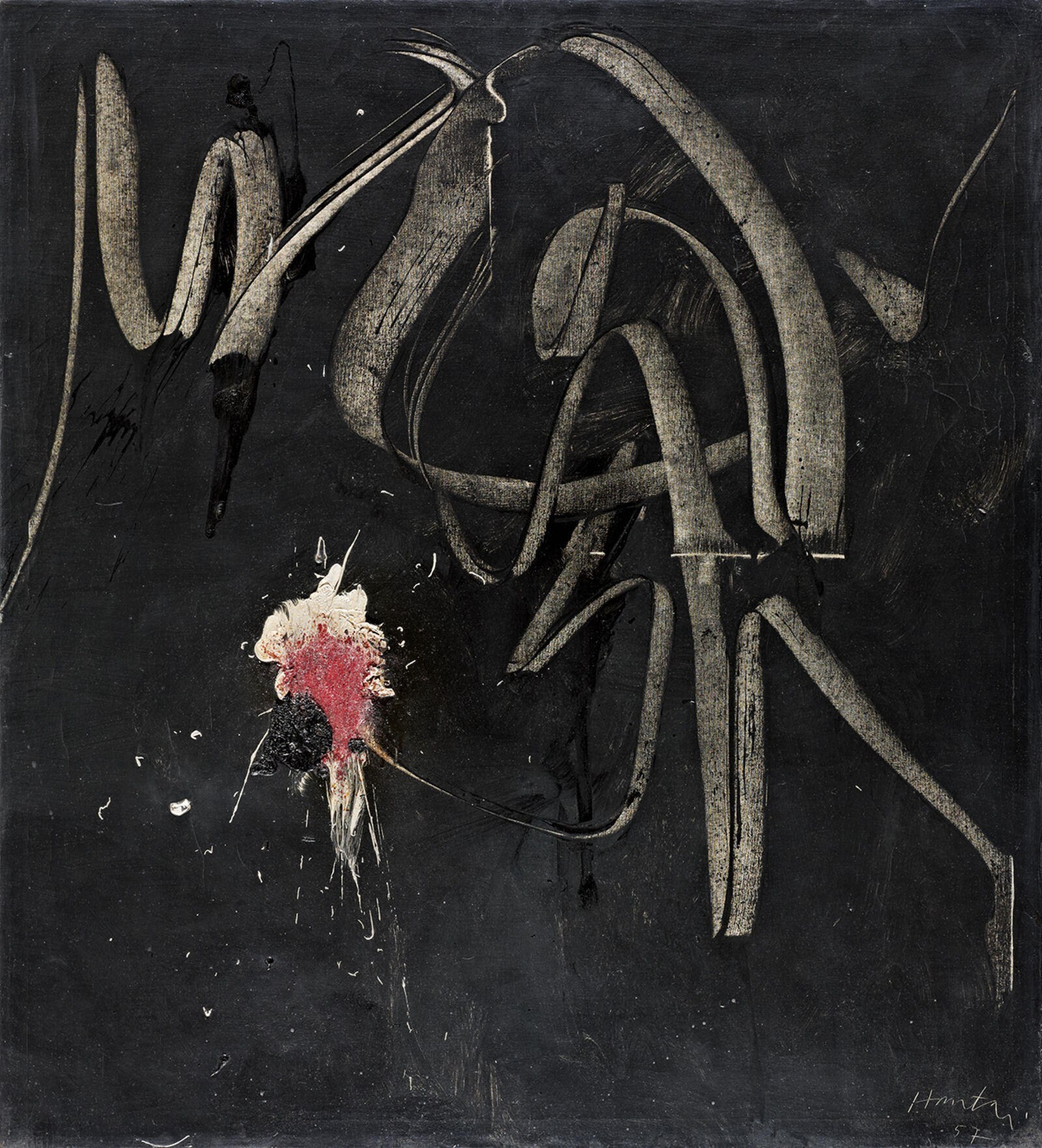

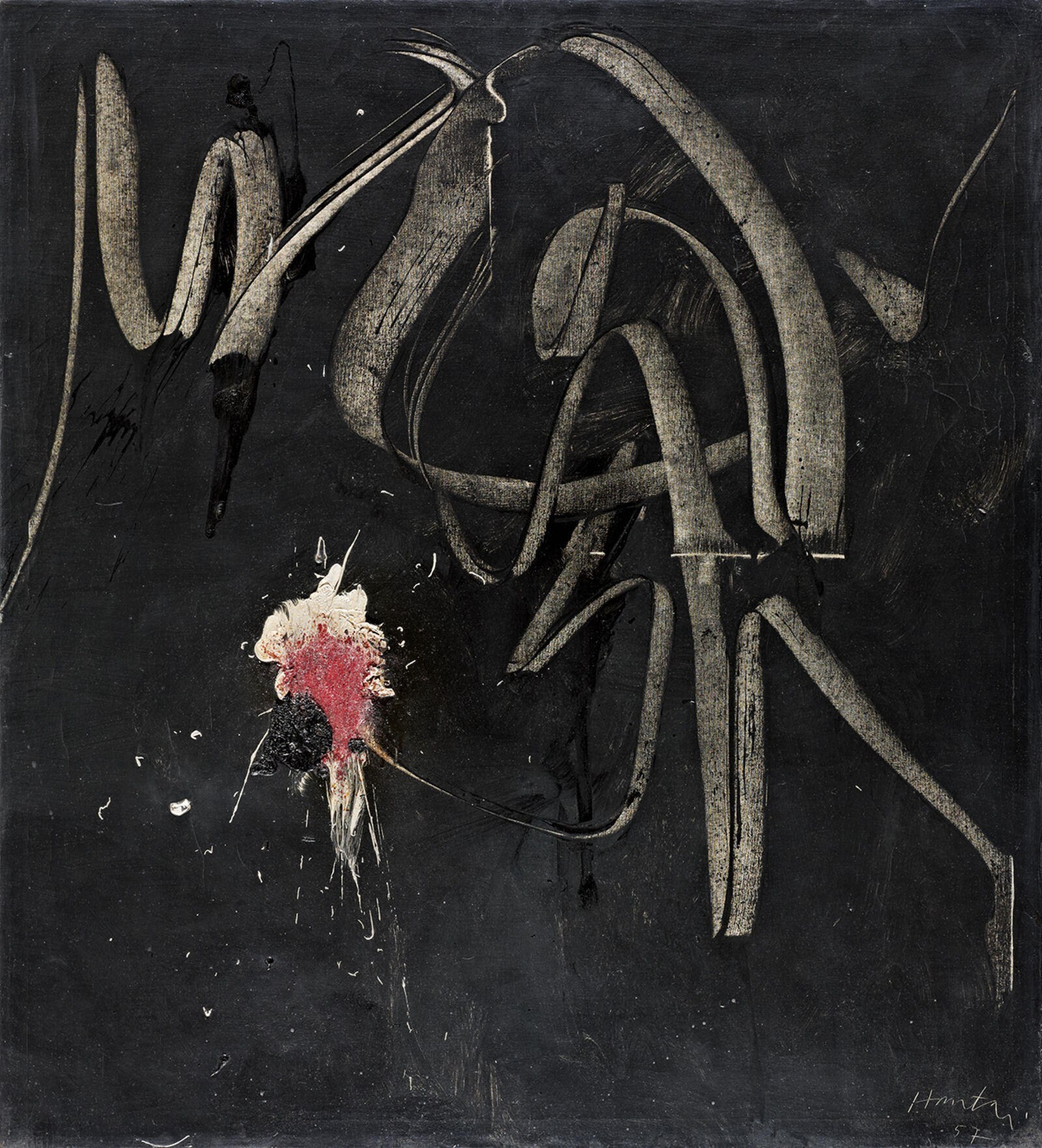

Simon Hantaï was born in Hungary in 1922 and, like Judit Reigl, was one of the many Eastern European immigrants in Paris. He too had studied in Budapest and had discovered the art of Jackson Pollock at the Venice Biennale in 1948. He was close friends with the American artist Joan Mitchell. With his impulsive visual language, he became an important proponent of European Action Painting.

Simon Hantaï: Peinture, 1957, Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Genève

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Genève. Fotografin: Sandra Pointet

The late 1940s saw the development of a specifically European version of Action Painting. Through the work of the Surrealists, artists were familiar with automatic processes of visual creation and continued to develop them in the painting of Art Informel.

The first solo exhibition of the work of Jackson Pollock in France took place in 1952. A number of large-scale drip paintings were on view, and the exhibition was attended by numerous avant-garde artists. In the accompanying catalog, the French gallerist Michel Tapié described the debut presentation of Pollock’s works as “a bomb in the Paris art world.”

Georges Mathieu had developed his dripping and pouring technique even before Jackson Pollock. Many of his calligraphic Action Paintings were completed in the space of only a few hours, in a burst of creative energy.

Georges Mathieu: Triumphal Return of Go Daïgo to Kyoto, 1957, Fondation Gandur pour l‘Art, Genève

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Image: Fondation Gandur pour l‘Art, Genève, Photographer: Sandra Pointet

Like Jackson Pollock, Georges Mathieu dripped fluid paint onto the canvas. Many of his monumental works were created within only a few minutes as performances in front of a large audience, making him an important precursor to Happenings.

In the early 1950s, Judit Reigl emigrated from Hungary to Paris, where she was initially associated with the Surrealists. Later, under the influence of the New York School, she experimented with impulsive, gestural painting.

Judit Reigl: Center of Dominance, 1958, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d'art moderne / Centre de création industrielle. Donation of the artist, 2011

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Image: © bpk / CNAC-MNAM / Georges Meguerditchian

Judit Reigl first encountered Abstract Expressionism in 1948 at the pavilion organized by Peggy Guggenheim at the Venice Biennale. From then on, Reigl stayed informed — primarily through magazines — about the works of the New York School, which especially interested her.

In many of her works, she slung industrial paint mixed with linseed oil onto the canvas, spreading it over the picture plane with her bare hands or metal tools. The playful integration of the artist’s own body into the creative process situates these strategies at the threshold of new forms of expression such as Happenings or Performance.

Ernst Wilhelm Nay: Hour Ypsilon, 1956, Kunstpalast Düsseldorf

© Ernst Wilhelm Nay Stiftung, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo: Kunstpalast - Achim Kukulies - ARTOTHEK

Under the Nazi regime from 1933 to 1945, the free creation of art and exposure to new developments from abroad had been almost impossible for German artists. As soon as the war ended, young painters began cultivating close international contacts and traveled to Paris.

By the early 1950s, West Germany had emerged as a center of Art Informel. For many artists, nonobjective painting seemed the only possible response to the horrors of war and the Holocaust. West German artists, too, embraced spontaneous, dynamic processes as the expression of a new sense of artistic freedom.

The only ones who perhaps have an inkling of freedom, because it is in their blood, because they are inveterate individualists and rebellious by nature — the artists — continue to be laughed at, hostile and insulted, as if the Nazis were still at the helm, as if the Third Reich with its hatred of ‘degenerate art,’ with its mendacious, stuffy, and kitschy aesthetics had remained victorious beyond its downfall. (...) Painting! I am trying to paint, I have set my mind on becoming a good painter. Isn’t that madness, after all that has happened?

Germany’s unique role in the Cold War, as well as the Federal Republic’s close connection to its Western allies, further encouraged the turn toward abstraction. As the perceived antithesis of the Socialist Realism of Communist East Germany, abstraction was politicized as the only valid form of expression for free democracies.

Accordingly, many art historians celebrated abstraction as the “universal” visual language of free modernity — a construct of the postwar period that informs art historical discourse to this day.

Winfred Gaul: Couleur et signification 1, 1958

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Image: Kunstpalast - Achim Kukulies - ARTOTHEK

In 1955, the painter Winfred Gaul joined “Gruppe 53,” an artists’ group that turned the city of Düsseldorf into a hub of Art Informel. The painting Couleur et signification (Color and Meaning) is closely related to both French Art Informel and American Action Painting.

One of the most important proponents of Art Informel in Germany was K. O. Götz. While visiting Paris, he met pioneers of Informel such as Georges Mathieu and Jean-Paul Riopelle and encountered works of Abstract Expressionism. In 1952, Götz began experimenting with a new painting technique that showed parallels to American Action Painting.

Karl Otto Götz: Giverny III/2, 1987, Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf - Stiftung Sammlung Kemp

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo:Kunstpalast - LVR-ZMB - Stefan Arendt - ARTOTHEK

The painting Giverny III/2 from the series Giverny is one of Karl Otto Götz’s late works. The title alludes to the glowing colors and flat compositions of the garden paintings of Claude Monet.

Another important artist of German postwar abstraction was Ernst Wilhelm Nay. In the 1930s, Nay had worked in a figural style influenced by German Expressionism. Under the Nazis, he was banned from painting and exhibiting.

He created his first nonobjective works in the early 1950s, drawing inspiration from the abstract pictorial language of Vasily Kandinsky, whom he had visited in Paris in 1943. Nay’s works were also well received early on in the United States.

Ernst Wilhelm Nay: Jota, 1959, Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Genève

© Ernst Wilhelm Nay Stiftung, Köln/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, Genève. Photographer: Sandra Pointet

In 1956, a selection of Scheibenbilder (disc paintings) by Ernst Wilhelm Nay were shown at the Venice Biennale, garnering him international fame as an artist.

Nay himself rejected the categorization of his pictures as Art Informel or Abstract Expressionism. Instead, he described his approach as “chromatic constructivism,” focused on the painterly exploration of nonperspectival space.

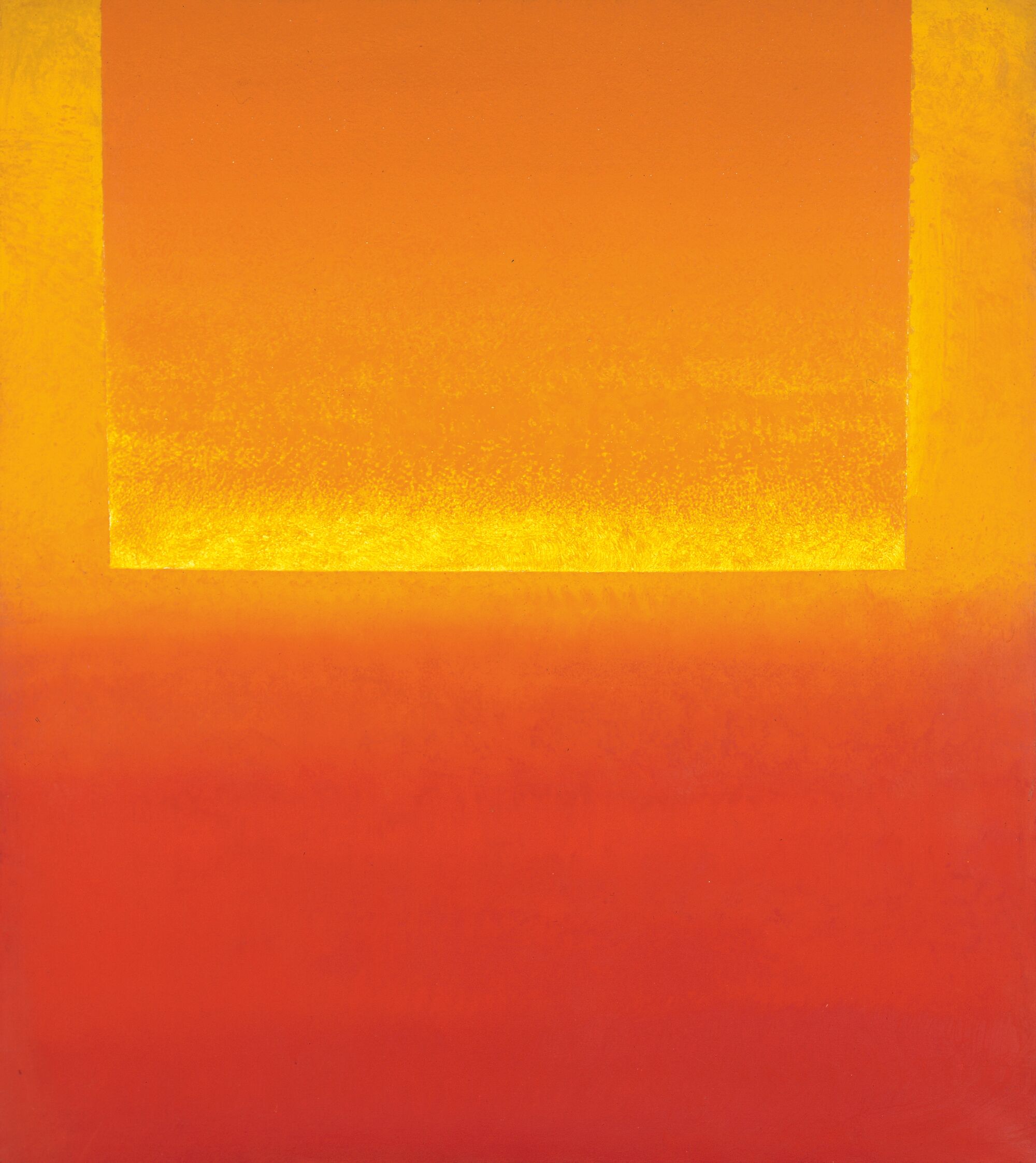

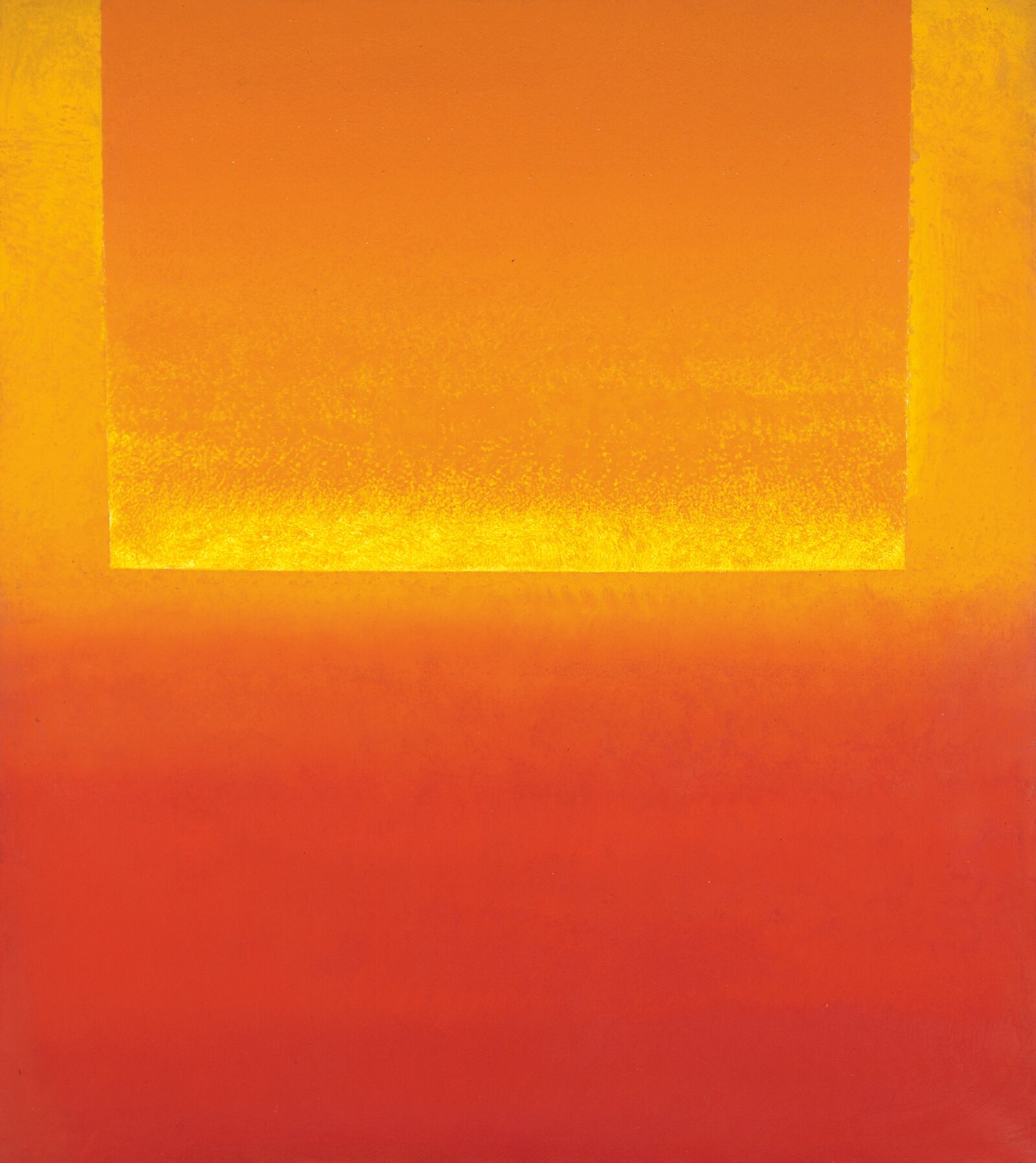

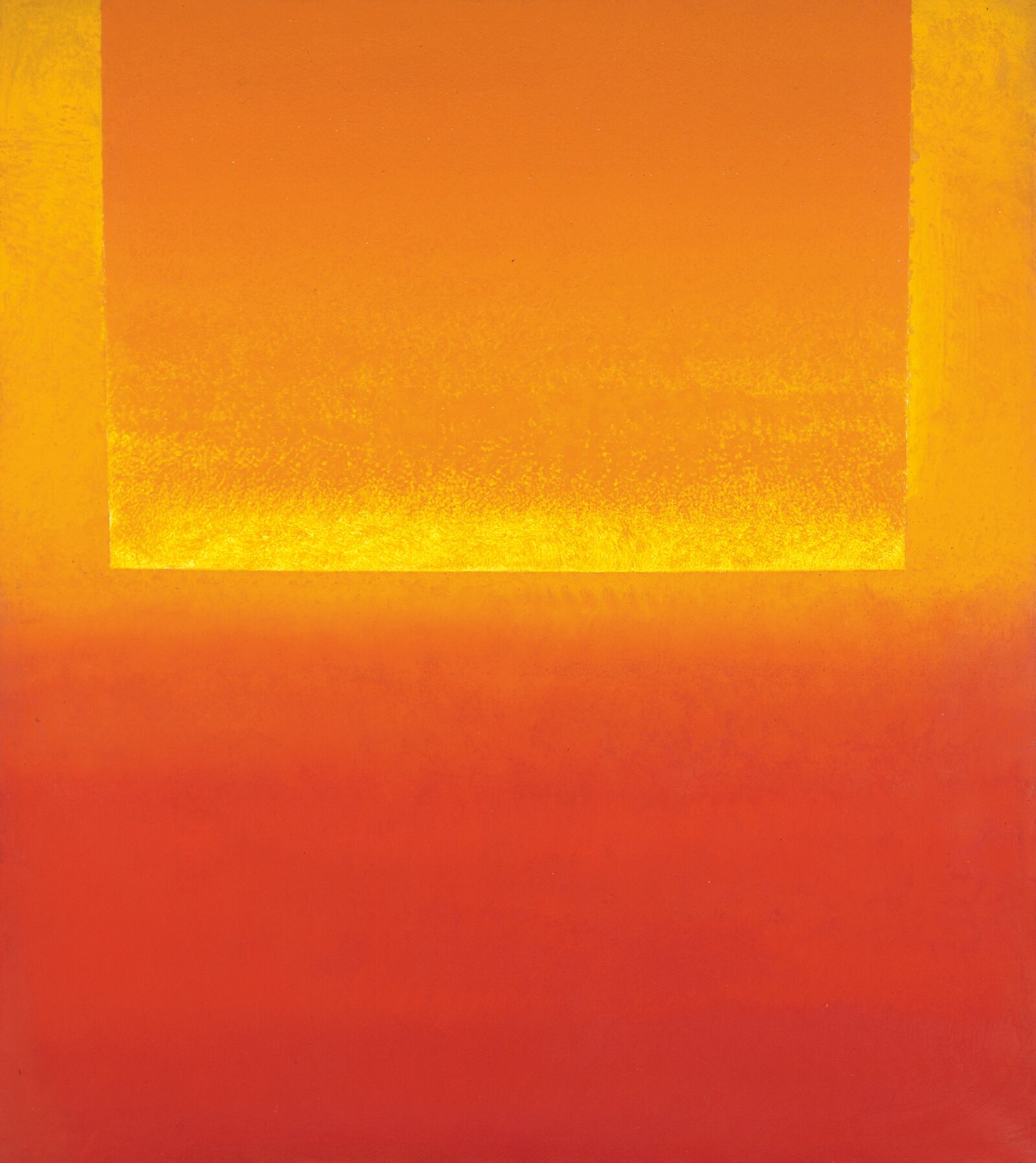

Already in the 1950s and 60s, a number of artists turned away from the impulsive gestures of Art Informel. One of them was Rupprecht Geiger, who helped found the artists’ group Zen 49, an important breeding ground for German postwar abstraction. The group’s focus was on meditative immersion in abstract visual spaces.

Rupprecht Geiger: 317a/61, 1961, Kunsthalle Mannheim

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Image: bpk / Kunsthalle Mannheim / Cem Yücetas

In the 1950s, Art Informel had established itself as the dominant style of the West German avant-garde. Many works created in reaction to Art Informel also show echoes of Abstract Expressionism. Yet the concern was not to imitate established pictorial formulas; between the poles of Action Painting and Color Field Painting, each artist engaged in an individual exploration of the tension between color and form, between the subjective gesture and the rational articulation of the picture plane.

Otto Piene: The Sun Is Burning, 1966, Kunstpalast Düsseldorf

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Bild: Kunstpalast - ARTOTHEK

Like Rupprecht Geiger, Otto Piene also distanced himself from the gestural expressiveness of Art Informel. In 1958, he cofounded the Düsseldorf artists’ group ZERO together with Heinz Mack. With their focus on the optical phenomenon of light, the painters propagated the idea of a “zero hour” as a radical new beginning for painting.

The transatlantic alliance of gestural abstraction also manifested itself in the early international reception of the two artistic directions. A key moment was documenta II in 1959, where works of Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel were presented as the expression of a universal language of abstraction. Notwithstanding the existence of national schools, free abstraction seemed the order of the day.

In his influential 1983 book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art, art historian Serge Guilbaut outlined the thesis that after World War II, New York established itself as the global epicenter of avant-garde painting, thereby superseding Paris. Moreover, it has often been observed that the United States, in particular, exploited free abstraction for purposes of propaganda during the Cold War. The political overtones of postwar abstraction, however, were of little importance to the artists themselves, who engaged in a mutually fruitful dialogue between equals.

With Abstract Expressionism in America and Art Informel in Western Europe, the two most important currents of international postwar abstraction matured at the same time. The two movements were marked by a profound kinship, drew from many of the same models and sources, and developed their radically new pictorial language in direct response to the upheavals of World War II. In particular, the dialogue between New York and Paris gave rise to many points of connection from the late 1940s on, enabling this creative exchange.

Now for the first time, the exhibition The Shape of Freedom showcases the intensity and lasting impact of this transatlantic dialogue.