Maurice de Vlaminck

He was a wild, independent, rebel artist—at least, that’s how the painter Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958) saw himself. His entire life long he styled himself an untrained, “impulsive barbarian,” a revolutionary loner and an outsider. It was an image he cultivated in his writings and that defines our perception of the artist to this day. But was it true

Vlaminck’s oeuvre is surprisingly multifaceted. Today, his works are found in the most important museums and collections worldwide.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

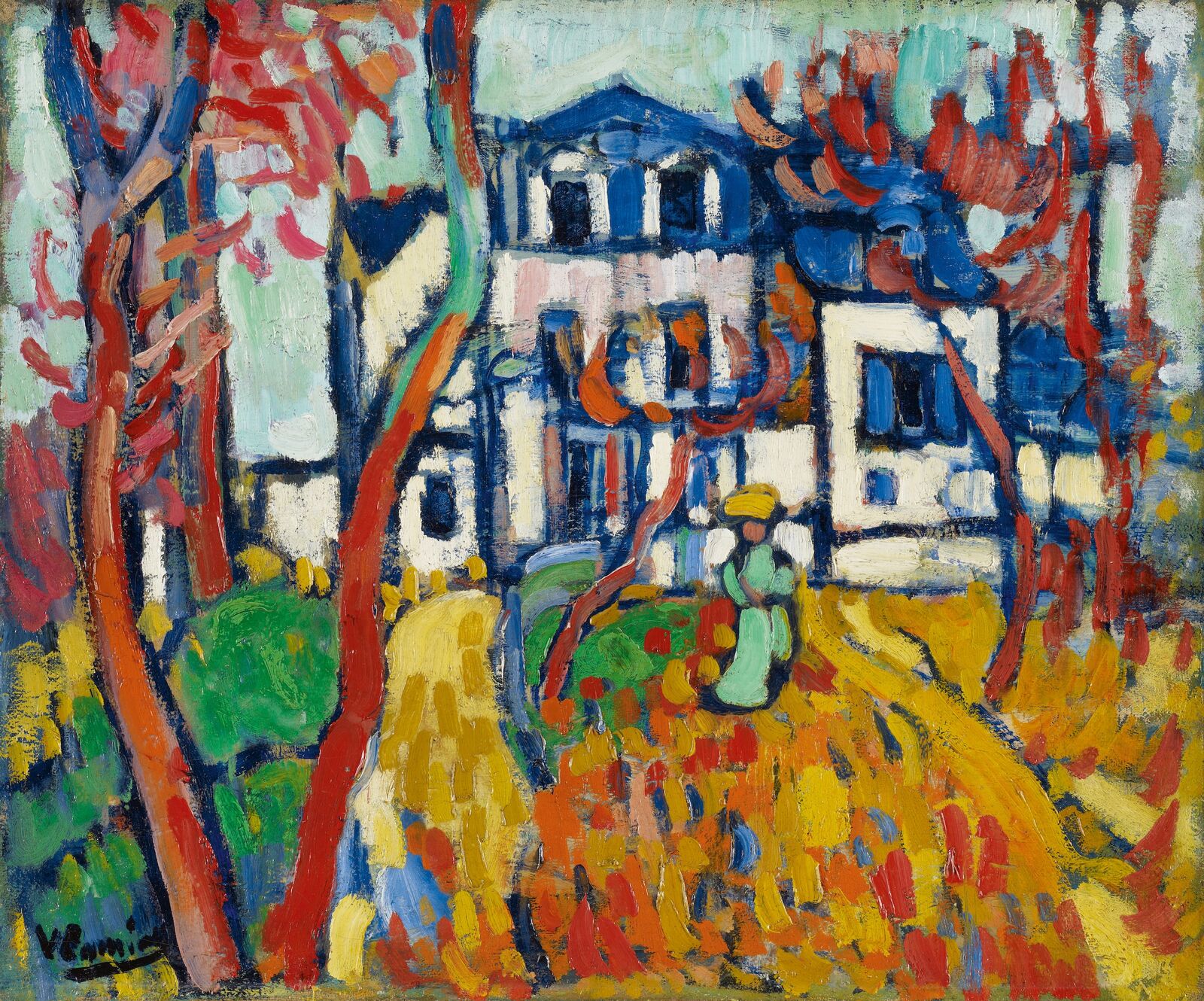

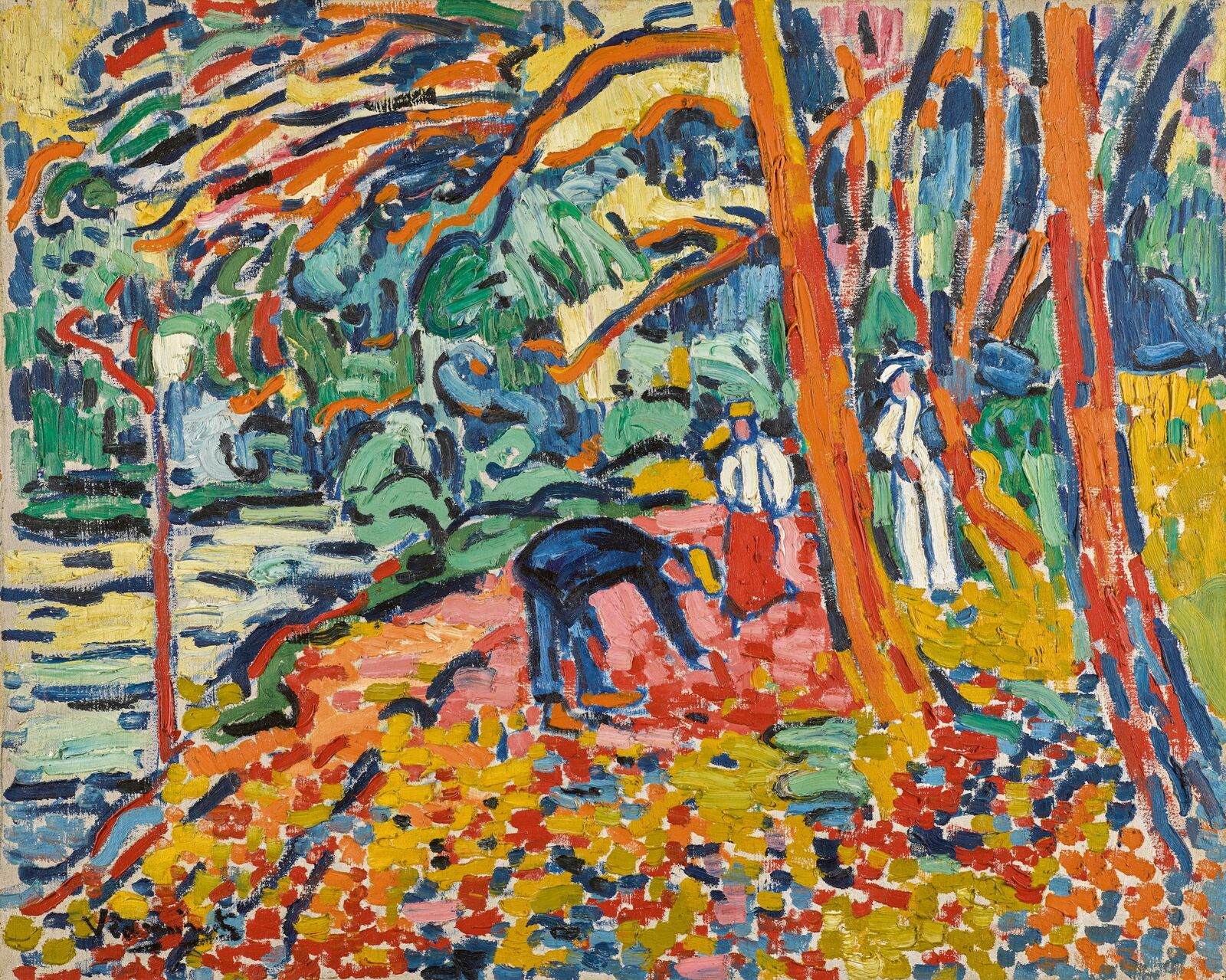

Maurice de Vlaminck: Underbrush, 1905, Private collection

With his brilliantly colored, expressive paintings, Vlaminck attracted attention from the very start. What at the time seemed shocking and disconcerting now appears full of intoxicating power, each brushstroke charged with energy. This furious, impetuous approach to painting became Vlaminck’s trademark.

I was a tender barbarian, filled with violence. I translated what I saw instinctively, without any method, and conveyed truth, not so much artistically as humanely.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

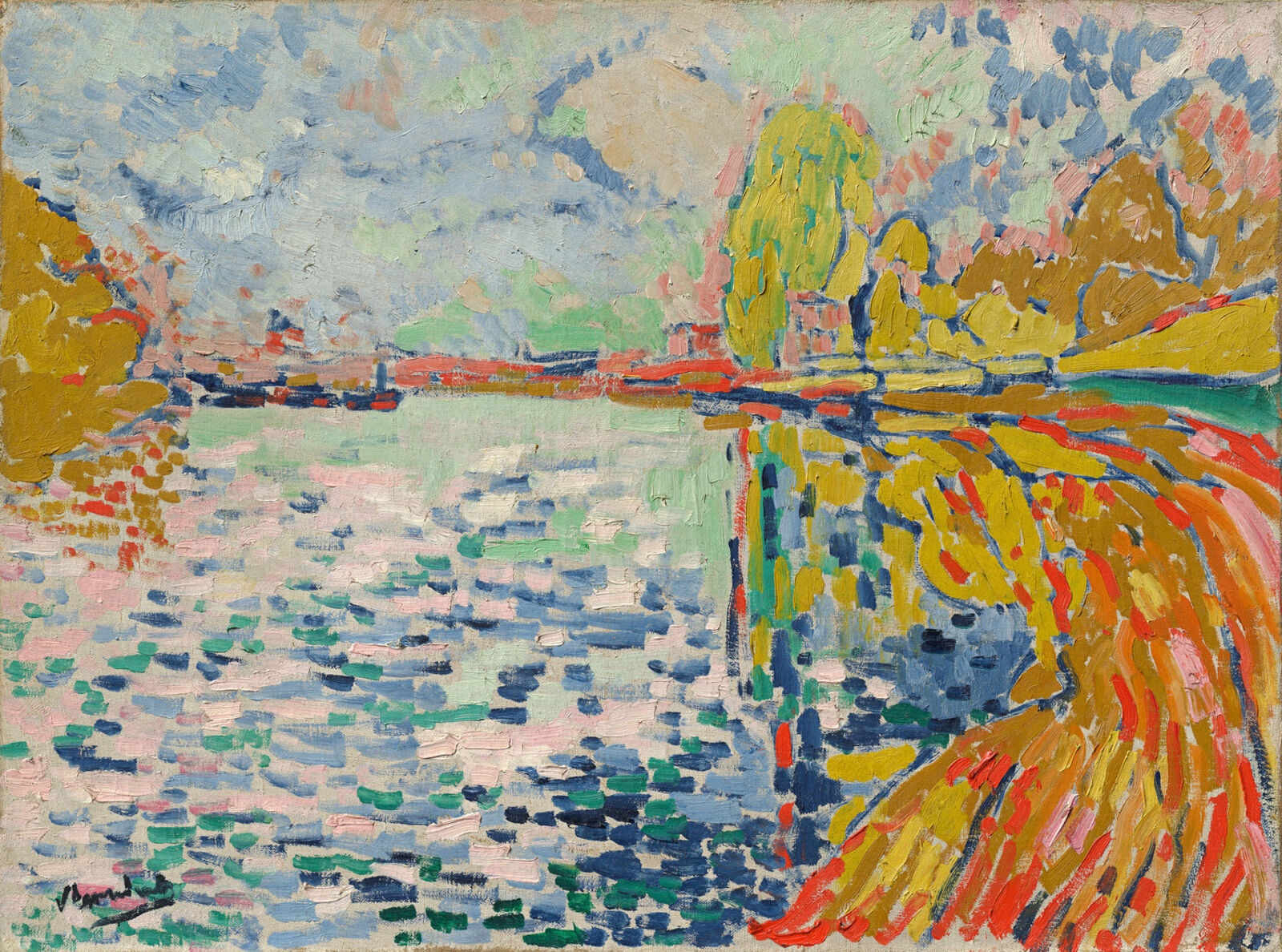

Maurice de Vlaminck, Banks of the Seine at Bougival, 1906, Hasso Plattner Collection

Yet Vlaminck did not work in isolation: he had connections to the networks of modern art and took careful note of developments in the art scene around him. With energy and a headstrong will, Maurice de Vlaminck helped forge new paths for painting in the twentieth century.

The exhibition Maurice de Vlaminck: Modern Art Rebel at the Museum Barberini is the first posthumous retrospective devoted to the artist by a German museum. With seventy-three works, it presents an overview of Vlaminck’s entire painterly oeuvre, from his Fauvist pictures, to his experiments with Cubism, to his little-known late work. Viewers can discover not only his famous landscapes, but also his stunning still lifes and figural paintings.

Socially, I was a born revolutionary . . . and in matters of art the same spirit boiled within me.

Maurice de Vlaminck: Woman with a Hat, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

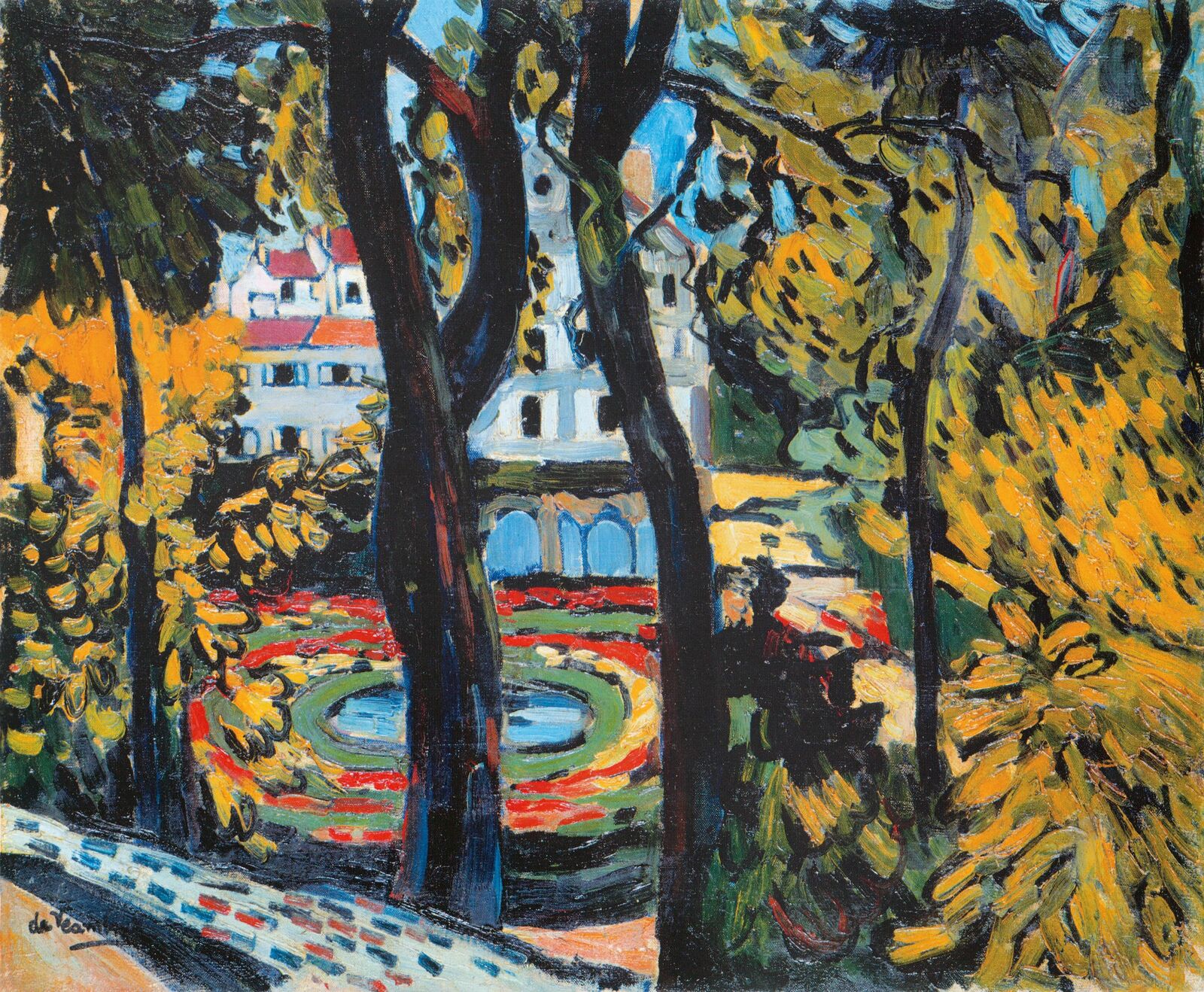

Pure color! At the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris, a group of young artists burst onto the scene with provocative paintings. One of them was Maurice de Vlaminck, who was only twenty-nine years old at the time. His friend André Derain also participated, as did Henri Matisse, who had already gained some notoriety. Though not an official group, the artists were kindred spirits.

Like the young Expressionists in Germany around the same time, these French artists radically asserted the expressive power of pure color. Critics perceived their bold hues as unbridled and uninhibited and soon dubbed them “wild beasts”—fauves in French. The artists themselves did not like the term “Fauvism”; only Vlaminck embraced it.

What is Fauvism? It is me . . . my way of combined revolt and liberation . . . my blues, my red, my yellows.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Maurice de Vlaminck: Park in Carrières-Saint-Denis, 1904, Privat collection

As a youth, Vlaminck had taken occasional painting lessons from a neighbor. Aside from that, he remained a proud autodidact, recognizing no limits to his freedom. He was contemptuous of academic tradition and claimed to have never seen the inside of a museum.

With my cobalts and vermilions, I wished to burn down the École des Beaux-Arts and to render my impressions without any thought for what has been achieved in the past.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/bpk | CNAC-MNAM

Maurice de Vlaminck: A Street in Marly-le-Roi, 1905/06, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d'art moderne / Centre de création industrielle

Rather than pursuing academic training in art, Vlaminck began earning his living as a passionate racing cyclist and a violinist, performing in cafés and the theater. At first, he painted only for enjoyment, finding his motifs in locales such as the nightclubs of Paris.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Girl from the Rat mort, 1905/1906, Private Collection, Courtesy Du LAC Fine Art, Paris

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/Ville d’Avignon/Musée Calvet

Maurice de Vlaminck: On the Counter, 1900, Musée Calvet, Avignon

Gaudy makeup and voluptuous corporeality mark the women as prostitutes. Unflinchingly, Vlaminck shows them in garish color, using bright red as a visual irritant. As a symbol, however, the color red also constituted a programmatic assertion of wildness and passion.

The landscapes covering the walls of the studio were so many challenges to the bourgeois whose idea of nature is of something tame and tidied up. Nevertheless, far from being put off by this outrance, I bought everything Vlaminck showed me.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Rural Luncheon, 1906, Private collection

The intrepid art dealer Ambroise Vollard staked everything on Vlaminck’s work and in 1905 purchased the entire contents of the artist’s studio. Previously, Vollard had also represented controversial artists like Vincent van Gogh and Pablo Picasso. From then on, Vlaminck was able to concentrate entirely on painting, and within only a few years produced an astonishing quantity of work. Spontaneity and rapidity were part of his strategy.

I was certainly glad for the reassurance he gave me, but at the same time, it struck me like a heavy blow!

Vlaminck always styled himself a self-made artist, free of all other influences. Yet there was one painter for whom his admiration knew no limits: Vincent van Gogh. Vlaminck embraced Van Gogh’s free, agitated brushwork, allowing the eye no resting place among the pulsating currents of color.

Maurice de Vlaminck: Route maraîchère, 1905, Kunst Museum Winterthur

Maurice de Vlaminck: Suburban Landscape, 1905, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Vlaminck discovered the painting of Van Gogh in 1901 at a solo show at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris. Apparently he was also impressed by Van Gogh’s misunderstood artistic genius: though unrecognized in his lifetime, Van Gogh was now experiencing growing renown.

When I saw his paintings, they seemed to me to be the ultimate solution, and because of my boundless admiration for the man and his work, his figure confronted me as an adversary.

Maurice de Vlaminck: Fisherman in Chatou, 1906, Private Collection

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/Courtesy of Sotheby’s

For Vlaminck, industrially manufactured oil paints were a given. They came ready to use, straight from the tube, and were easily available at the paint dealer’s shop. The practicality of tube paints had already enabled the Impressionists to work in the open air, but as Vlaminck realized, they also made it possible to achieve entirely new effects. He often squeezed pure color directly from the tube onto the canvas.

I squeezed and ruined tubes of aquamarine and vermilion.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Maurice de Vlaminck: Forest Scene, 1906, Private collection

The swiftness of the painting process is obvious, in keeping with Vlaminck’s self-portrayal as a “barbaric” artist driven by instinct and wild creative fury.

Maurice de Vlaminck: Bougival, 1905, Dallas Museum of Art

Maurice de Vlaminck: View of Bougival, 1906, Tel Aviv Museum of Art

He applied the paint unmixed and unthinned, straight from the tube. The saturated tones glow with remarkable intensity. In his choice of hues, Vlaminck was less interested in realism than in expressive power.

I heightened all my tonal values and transposed into an orchestration of pure color every single thing I felt.

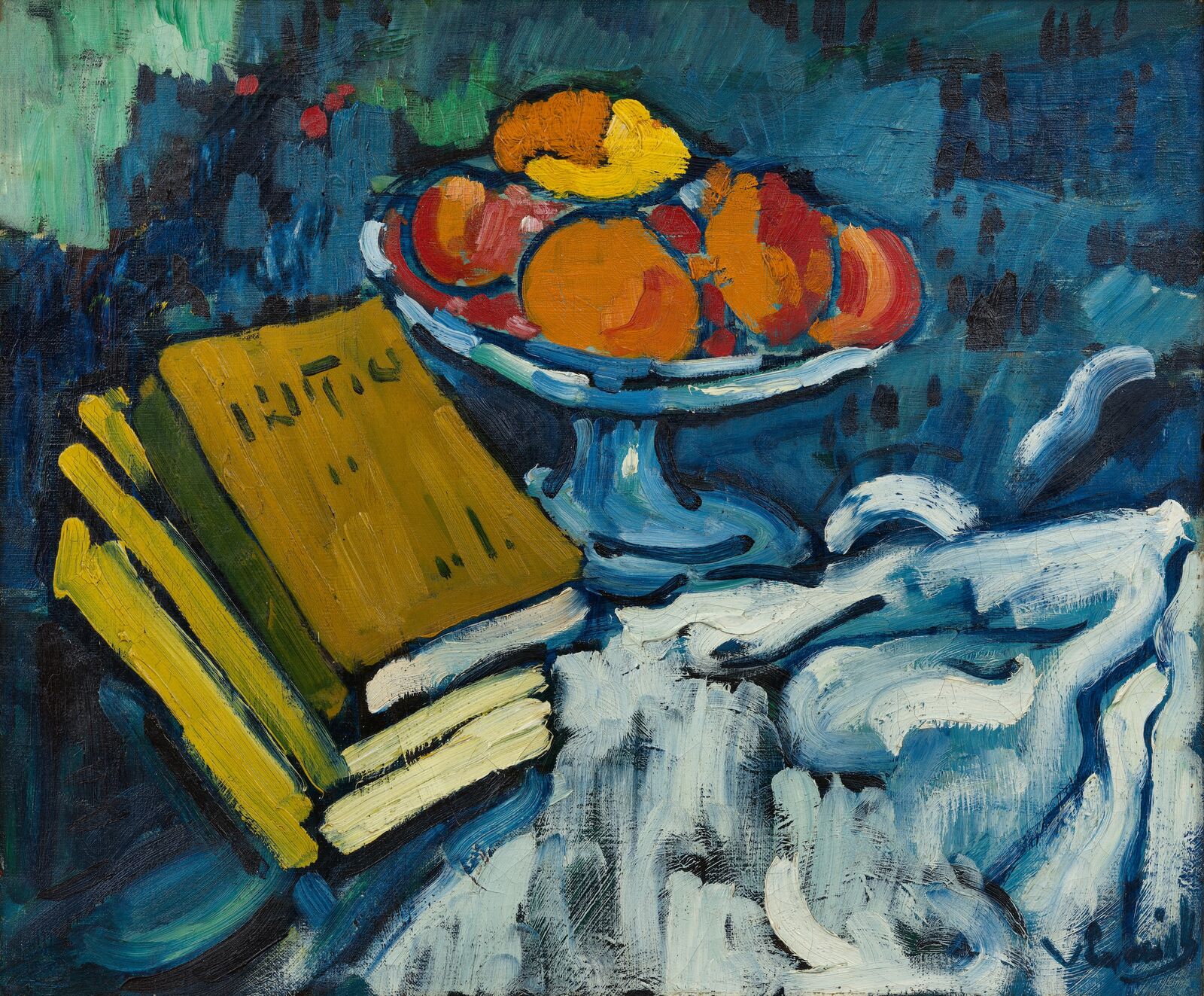

Vlaminck favored still life as a motif especially in the winter, when he was unable to work outside. Other Fauve painters also explored this traditional subject, since it lent itself to visual experimentation more than any other genre. Such experiments are precisely what we find in Vlaminck’s still lifes. His Fauvist arrangements of everyday objects seem anything but “still”; marked by powerful color contrasts, they vibrate with energy.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/Artistica Art Collection Limited, Nikosia

Maurice de Vlaminck: Still Life with Books and Fruit Bowl, 1906, Private collection

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

Maurice de Vlaminck: Still Life with Vase, Pitcher, and Fruit Bowl, 1907, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

Working in the studio, the self-described artist-rebel and “wild barbarian” patiently arranged fruits and dishes on a table. In his still lifes, he continued his studies and tested new possibilities for the design of pictorial space.

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Fishermen, 1907

Hasso Plattner Collection / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Reflections on the waves and green riverbanks: Vlaminck’s favorite and most frequently painted subjects were the river landscapes and villages along the Seine. In this regard he followed in the footsteps of the Impressionists: like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, Vlaminck worked en plein air amid changing weather conditions, painting directly from the motif.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/Andres Kilger

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Bridge at Chatou, 1906/07, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

The towns along the Seine River were familiar to Vlaminck. Here he knew his way around: he had grown up in Le Vésinet and Chatou, and later explored the region on extended bicycle tours up and down the river, finding the best spots for painting.

Hasso Plattner Collection / VG-Bild Kunst, Bonn 2024

Maurice de Vlaminck: Rueil, the Boathouse, 1906

For me, the discovery of the outside world dates from my acquisition of a bicycle. I spent whole days on the high-road. I rode through villages, towns and the countryside. I tasted dust; rain poured down on me; I struggled against the wind.

In many paintings, Vlaminck turns his attention to the water, using powerful, distinct brushstrokes to give the scenery a sketch-like appearance. He omits details and abstracts nature, using strategic contrasts to intensify the coloristic effect: the cobalt blue of the water seems luminous, juxtaposed with the red house roofs on the riverbank.

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Bride at Chatou, 1906/07, Hasso Plattner Collection

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Bridge at Chatou, 1908, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud, Cologne

Unlike the Impressionists, Vlaminck did not show holiday seekers from the big city. His interest was in the economic function of the river and the world of work, with puffing smokestacks, imposing industrial complexes, modern steamers, and barges on the Seine.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/Artizon Museum, Ishibashi Foundation, Tokyo

Maurice de Vlaminck: Canal Boat, 1905/06, Artizon Museum, Ishibashi Foundation, Tokyo

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Seine at Nanterre, 1906/07, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

During his time in the military around 1900, Vlaminck had become politically conscious and had devoured the writings of anarchists. He published articles advocating for the dispossessed and in support of striking workers. He openly professed anarchism and rebelled against militarism and nationalism. In painting, he found a safety valve—and freedom to overturn rigid rules and traditional norms.

What I could have done in life only as an anarchist, to throw a bomb—which would have sent me to the scaffold—I sought to realize in painting through the exclusive use of pure colors.

Maurice de Vlaminck: Saint-Michel District, Bougival, 1913

Hasso Plattner Collection / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

The play of pure color and nothing else, taken to an extreme, this frenzy into which I had so fervently thrown myself, no longer satisfied me.

Eventually the bright colors of his Fauvist phase were no longer enough for Vlaminck, and his painting began to change. He struck out in a new direction, distancing himself from Fauvism. From around 1907 on, Vlaminck transitioned to a darker, more muted palette. At the same time, he now showed a keener eye for the observation and development of geometric structures.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/DACS (Photo: Tate)

Maurice de Vlaminck: Landscape near Martigues, 1913, Tate, London

Ocher-colored fields extend under a matte blue sky: Vlaminck painted the landscape near Martigues in the Provence in the South of France. The painting seems like an homage to Cézanne, who often depicted similar motifs.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Maurice de Vlaminck: Sailboats at Chatou, ca. 1908, Nahmad Collection

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Maurice de Vlaminck: Still Life, 1910/11, Privatsammlung, Courtesy Galerie de la Présidence, Paris

Between 1905 and 1907, a genuine “Cézanne fever” broke out in Paris. Several major exhibitions following the death of the pioneering artist prompted his rediscovery and fueled the emerging movement of Cubism. Attentively, Vlaminck observed these new developments.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Maurice de Vlaminck: Opium, ca. 1910, Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

A flirtation with Cubism? The angular, fragmented forms recall Cubist works by Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque. Although Vlaminck later disparaged Cubism, from 1908 on he experimented with the dissection of form and Cubist strategies of representation. This phase, however, would remain a short one, ending with the shattering outbreak of World War I in Europe. For Vlaminck, too, the war represented a caesura.

The war taught me a great lesson. All my confidence in civilization, science, progress, socialism has been destroyed. . . . I don’t believe in anything any longer. . . . I don’t even believe in painting anymore!”

Maurice de Vlaminck: Harvest during Approaching Thunderstorm, 1950, Fonds de dotation Maison Vlaminck

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

After World War I, Maurice de Vlaminck turned his back on avant-garde experimentation. As a young Fauvist painter between 1904 and 1908, the self-described rebel had once played a decisive role in pioneering modern painting. Now, however, he returned to previous modes of art, developing an idiosyncratic version of Post-Impressionism in his late work.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/bpk | RMN - Grand Palais | Hervé Lewandowski

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Fire, 1945, RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay), on permanent loan to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Chartres

During the German occupation of France (1940–44), Vlaminck rejected the French avant-garde and polemicized against it, unabashedly praising the vitality of Nazi art and culture. At the same time, however, his own works fell victim to the reactionary artistic policies of the Nazis and were removed from German museums as “degenerate.”

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024/bpk | CNAC-MNAM | Photo: Christian Bahier/Philippe Migea

Maurice de Vlaminck: Houses with Thatched Roofs, 1933, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris

In his late works, Vlaminck presents nature as inscrutable and awe-inspiring. Dark clouds race across the sky; powerful storms draw near. The painter uses strong contrasts of light and dark to intensify the oppressive atmosphere.

Maurice de Vlaminck: Landscape, 1930, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Maurice de Vlaminck: The Grainstacks, 1950, RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay), on permanent loan to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Chartres

The grainstacks stand out against the horizon, harsh and massive. Vlaminck returned to this agrarian subject again and again in his later years. The motif of grainstacks had been made famous by Claude Monet, who inscribed it in art history in a pioneering series of sunlit views, flickering with color. In Vlaminck’s scene, however, the sky is brooding. Does it signal a repudiation of progress and modernization? In any event, it bears witness to the artist’s rejection of the avant-garde of his day.

True liberation is found within . . . and the freedom within oneself is endless.