Impressionism in Russia

Russian painters of the late 19th century were introduced to Impressionism in the French art metropolis of Paris. This encounter had a lasting effect: when they returned to Russia, they painted en plein air and sought to capture fleeting moments of everyday Russian life. The Impressionist exploration of light inspired not only the Russian Realists, but also the young artists of the early 20th-century Russian avant-garde.

From Repin to Malevich

With over 80 works by artists from Ilia Repin to Kazimir Malevich, the exhibition in the Museum Barberini reveals the international character of art around 1900 and illuminates a fascinating chapter in the history of Impressionism that until now has received little attention.

This Barberini Prolog explores the intense exchange of artists, motifs, and ideas across national boundaries. Russian painters adopted the Impressionist visual language and continued its legacy in a variety of lively and headstrong ways, with sunlit landscapes, vivid portraits of their contemporaries, and direct impressions of Russian life. With their painterly experiments, Russian artists advanced to the very threshold of abstraction.

Ilia Repin: Along the Field Boundary: Vera Repina Is Walking along the Boundary with Her Children, 1879, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Kazimir Malevich: Sisters, 1930, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Nicolas Tarkhoff: Carnival Day in Paris, 1900, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

In the late 19th century, many Russian painters went to Paris. They immersed themselves in the life of the modern metropolis, with its traffic, speed, crowded boulevards, and brightly lit nights.

The Russian Realism they had learned at the Imperial Academy in St. Petersburg and the Moscow Art School was inadequate to capture this excitement, but in Impressionism they found a style of painting capable of expressing the feeling of life in Paris.

Korovin and Tarkhoff in Paris

The Russian painter Konstantin Korovin encountered the Impressionists when he came to France in 1887. Their loose brushwork, vibrating effects of light, and lively motifs appealed to him. In the following years he returned to Paris again and again. His pupil Nicolas Tarkhoff also painted the Parisian cafés and boulevards under differing weather conditions and at different times of day. Tarkhoff enjoyed international success and exhibited with the Impressionists in Berlin, Venice, and Moscow.

Konstantin Korovin: Paris: Café de la Paix, 1906, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Nicolas Tarkhoff: Street in the Parisian Suburb of Saint-Martin, 1901, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Konstantin [Korovin] loved Paris; he loved the noisy, colorful crowds on the boulevards. The friendliness and joie de vivre of the French were entirely to his liking.

Valentin Serov: Lelia Derviz, 1892, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

French Impressionism encouraged Russian artists to embrace lighthearted motifs and a free approach to painting. Working in the open air imbued their paintings with a new, carefree spirit.

Instead of the weighty, socially critical, and serious themes of Russian Realism, they now explored moments from everyday life. The private realm now became viable subject matter, and artists painted sunlit motifs showing their own lives with friends and family members.

The great Realist Ilia Repin was one of the first Russian artists to recognize the potential of Impressionism.

In 1873, a scholarship from the academy in St. Petersburg enabled him to spend several years in Paris. When he returned to Russia, he painted Along the Field Boundary, showing his wife Vera with their children and governess in the countryside near Moscow—a motif entirely in the spirit of Claude Monet.

Ilia Repin: Along the Field Boundary: Vera Repina Is Walking along the Boundary with Her Children, 1879, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Konstantin Korovin: Summer: Lilac, 1895, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Konstantin Korovin’s small painting Summer: Lilac of 1895 seems like a study of the corner of a garden with a rain barrel; the girl smelling the lilacs appears almost as an afterthought. The traditional hierarchy of primary and secondary subject matter in Russian art is suspended in Korovin’s paintings: what matters is the moment, experienced with all the senses.

My single and most important goal, which I tirelessly pursued in the art of painting, was always beauty, ... enchantment through color and form. Never didactic, never an agenda or protocol of any kind.

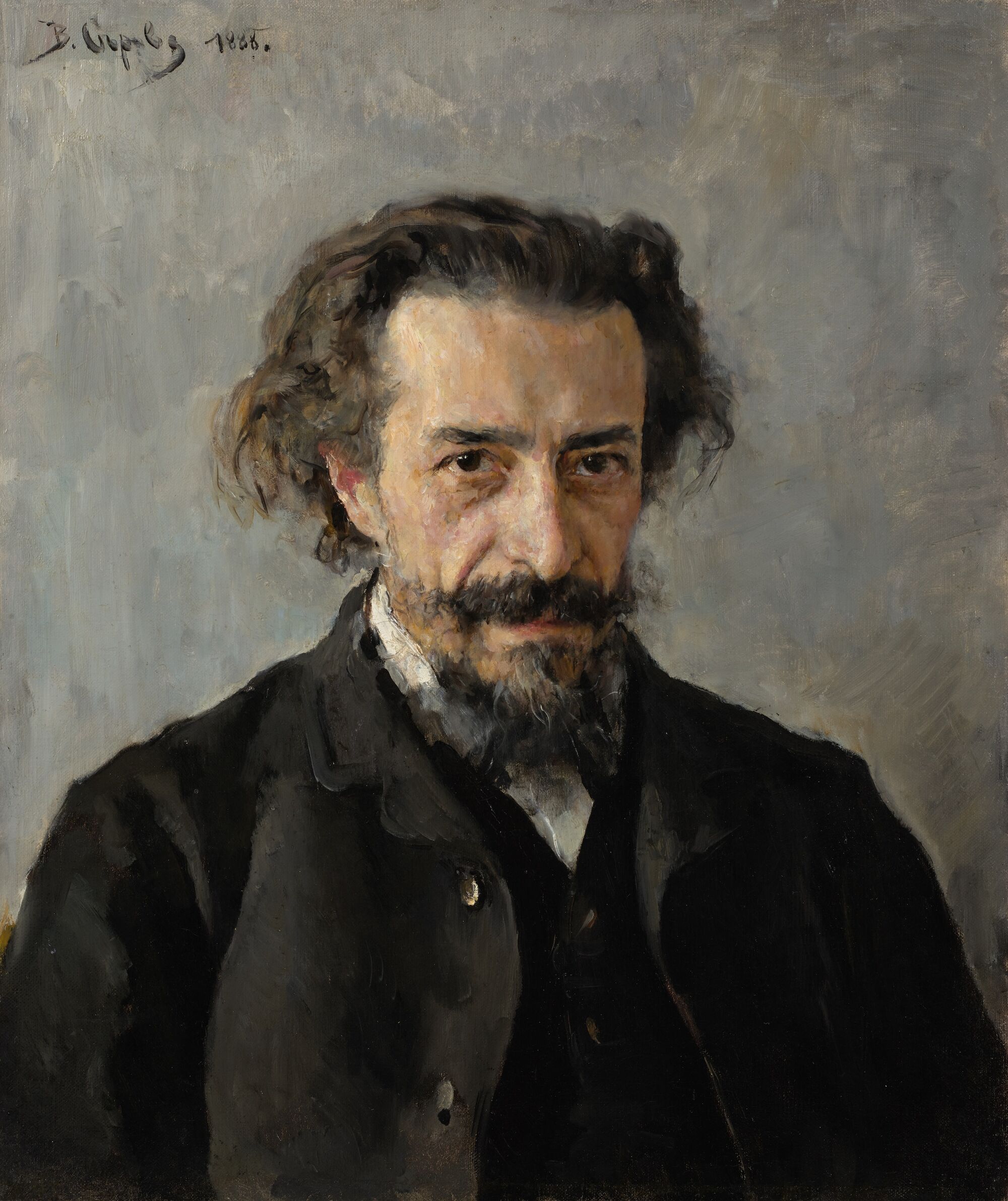

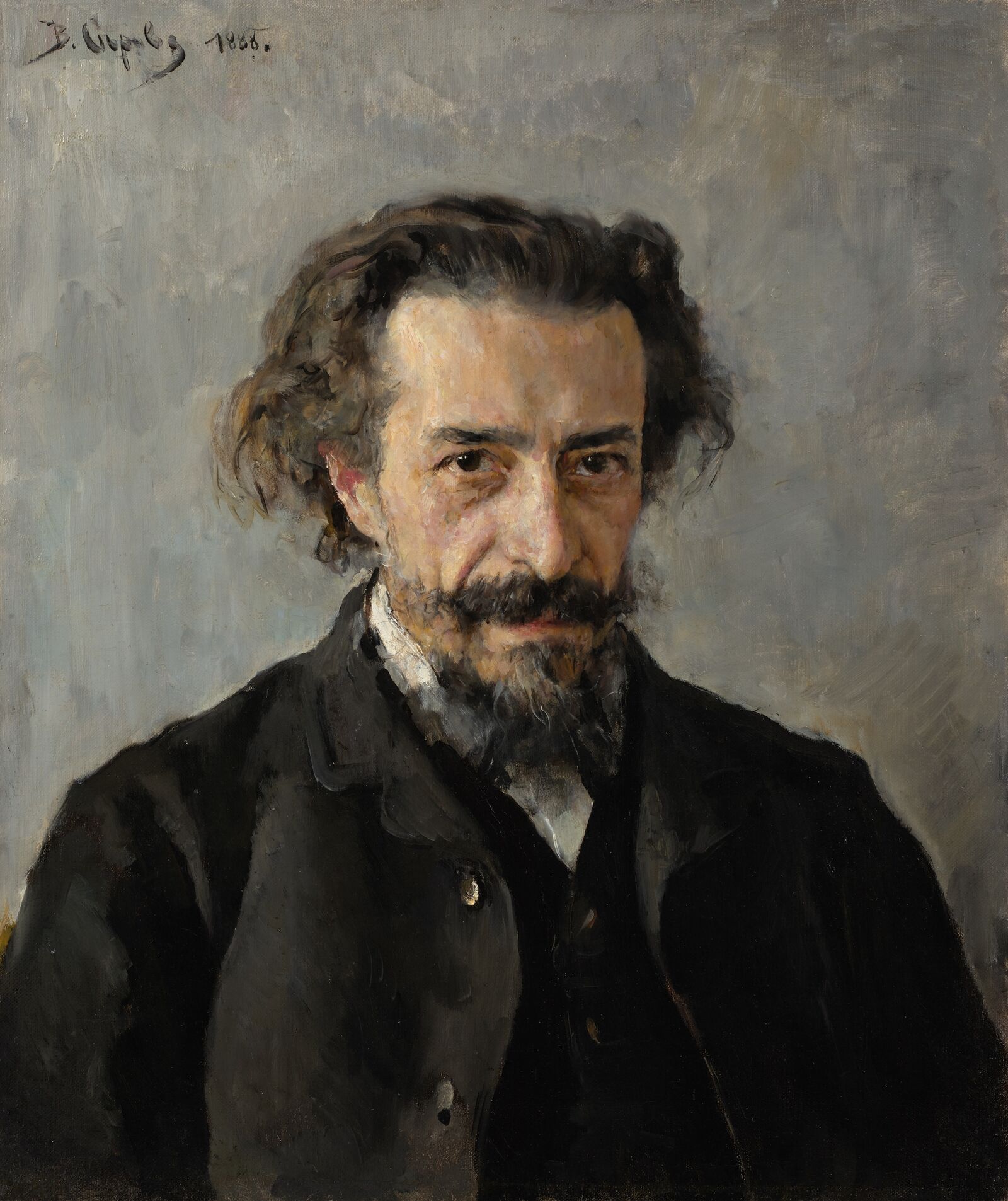

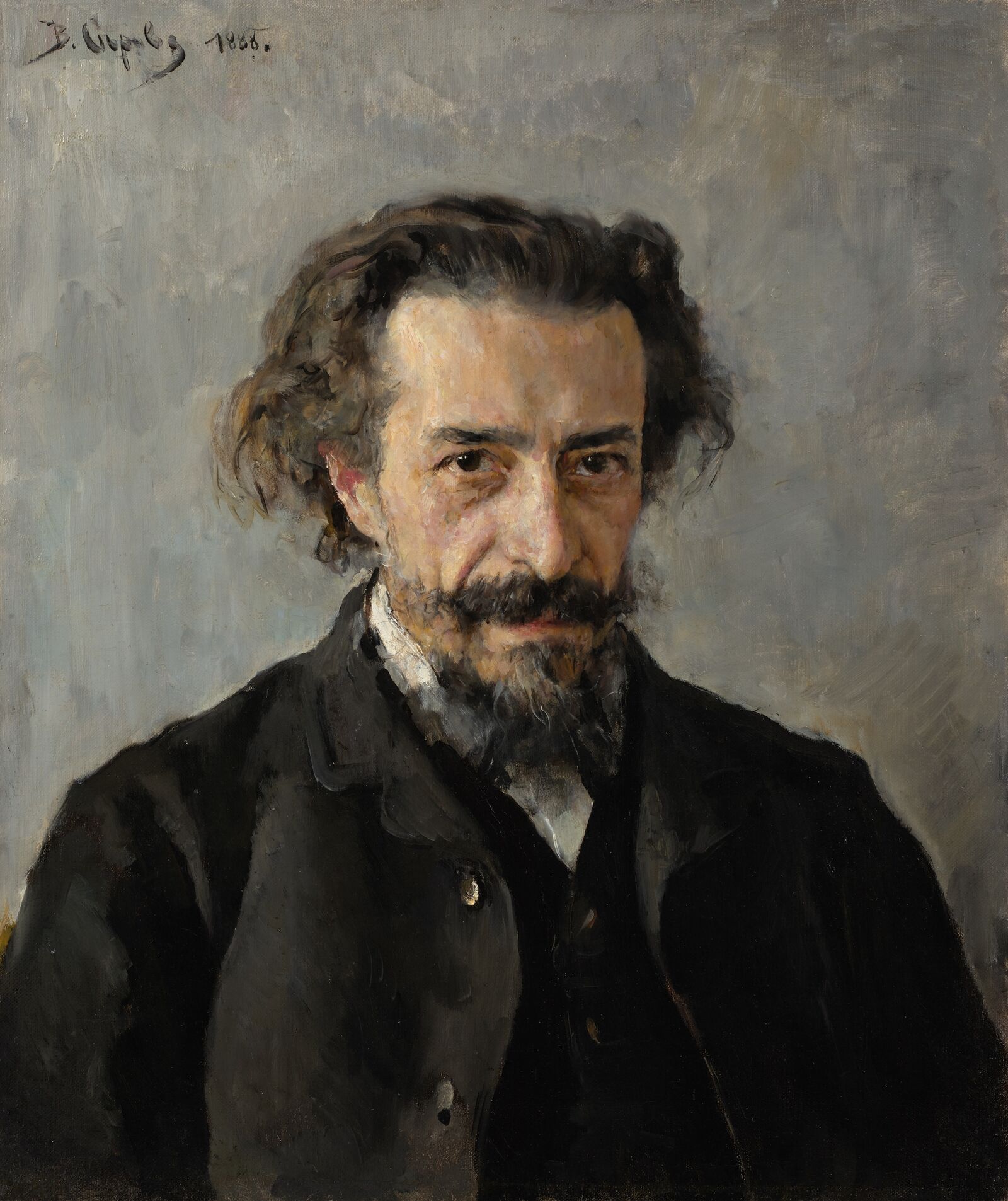

Valentin Serov: Portrait of the Composer Pavel Ivanovich Blaramberg, 1888, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

How much expansive elegance and fleeting buoyancy can Russian Realism convey? Portrait painters explored this question by depicting well-known Russian personalities—actresses, writers, or fellow painters—in an expressive, spontaneous manner, as if in a moment captured by chance. Their portraits show the influence of Impressionism, while still striving to embody the character and personality of the subject.

Humanity has always valued those works of art that express, as completely as possible, the drama of the human heart or, to put it simply, the inner character of a person.

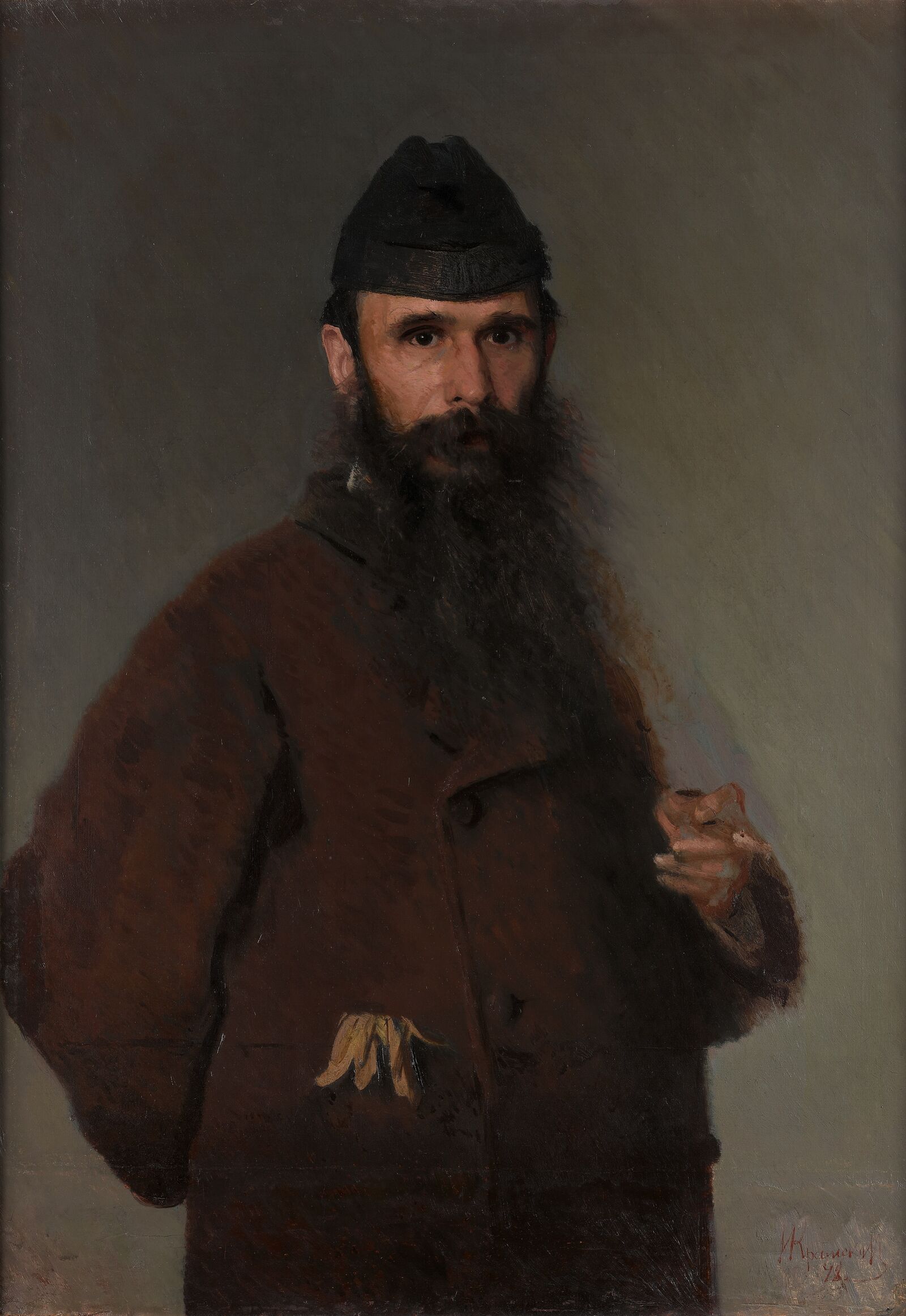

Ivan Kramskoy: Portrait of the Painter Aleksandr Dmitrievich Litovchenko, 1878, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The painter Aleksandr Dmitrievich Litovchenko poses casually, cigar in hand. The work was commissioned by the collector Pavel Tretyakov from the portrait painter Ivan Kramskoy. As a founding member of the Peredvizhniki (“Wanderers”), one of the most influential artists’ groups in 19th-century Russia, Kramskoy was a proponent of Critical Realism. In 1876, however, he traveled to Paris to investigate Impressionism, and his visible brushstrokes bear witness to the influence of Edouard Manet.

As I drew near to Litovchenko’s portrait, suddenly I was startled: there he stood in front of me, in the flesh, though I do not know him personally. What a magician this Kramskoy is! That’s not a canvas—it’s alive…

Konstantin Korovin painted the aspiring opera singer Tatiana Spiridonovna Liubatovich in 1889. Both of them belonged to the circle of the businessman and patron Savva Mamontov. An artists’ colony with writers, composers, and painters had formed at Mamontov’s estate in Abramtsevo near Moscow; there, far from the pressures of the official cultural institutions of tsarist Russia, new artistic currents such as Impressionism could develop freely.

Konstantin Korovin: Portrait of the Opera Singer Tatiana Spiridonovna Liubatovich, 1889, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

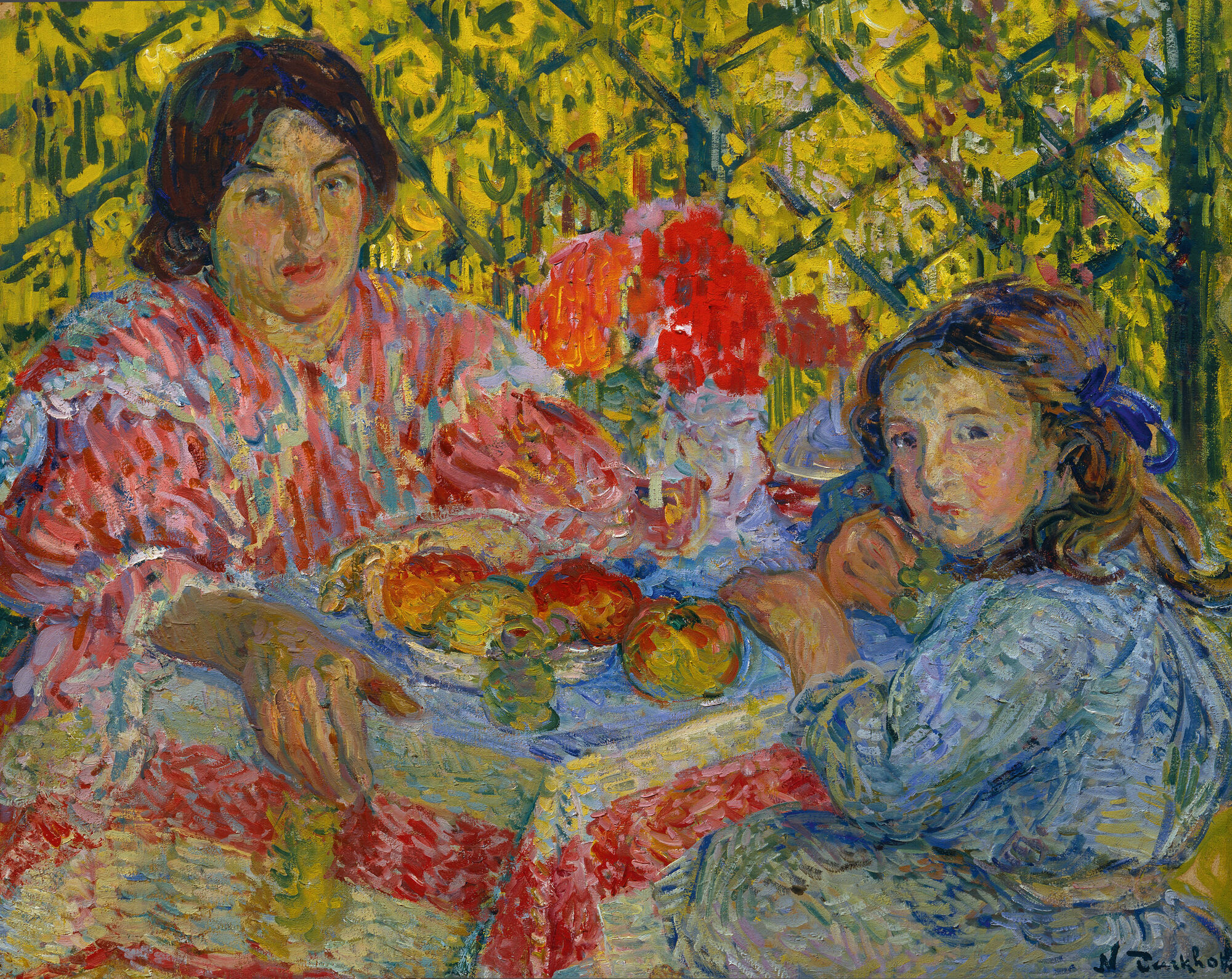

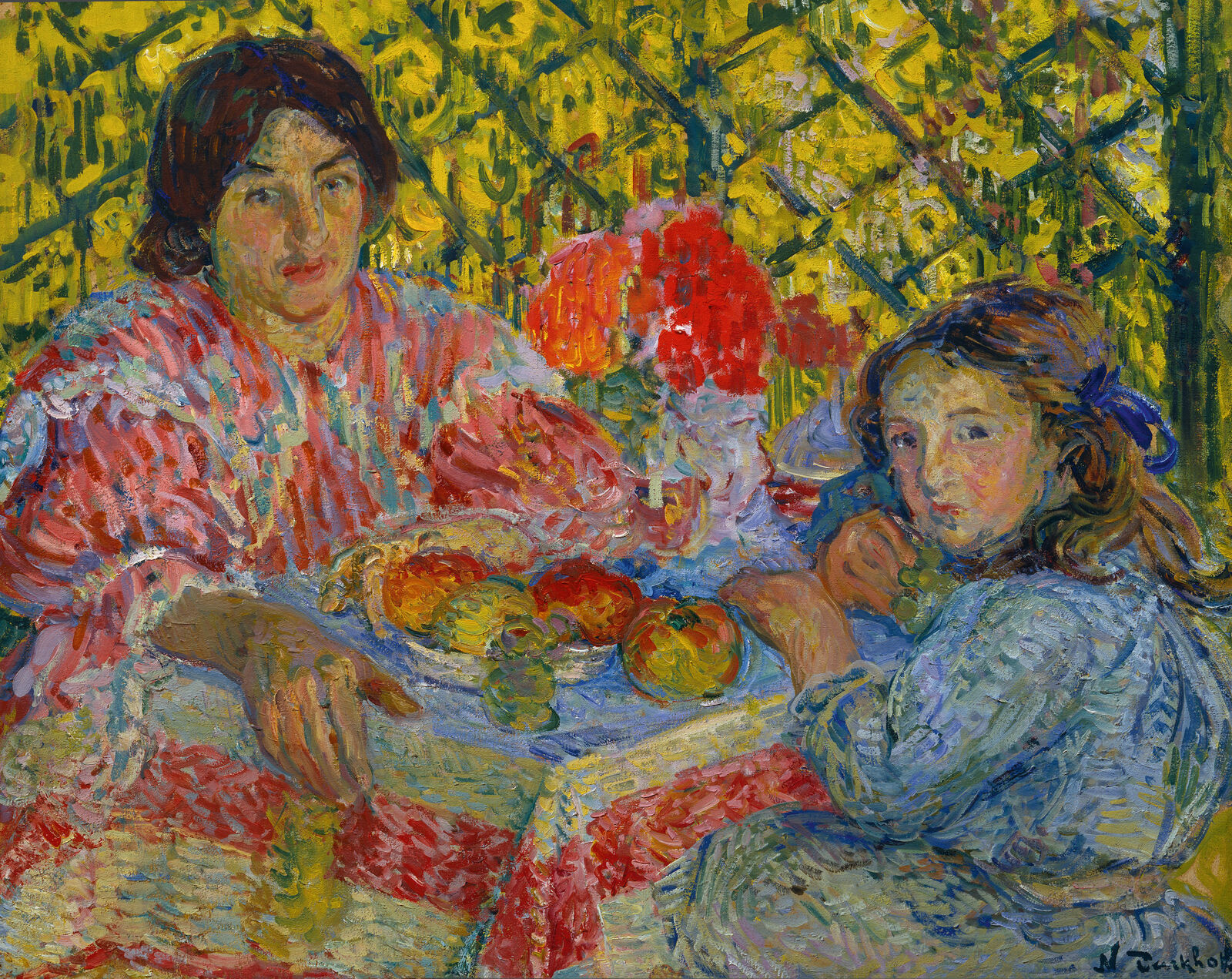

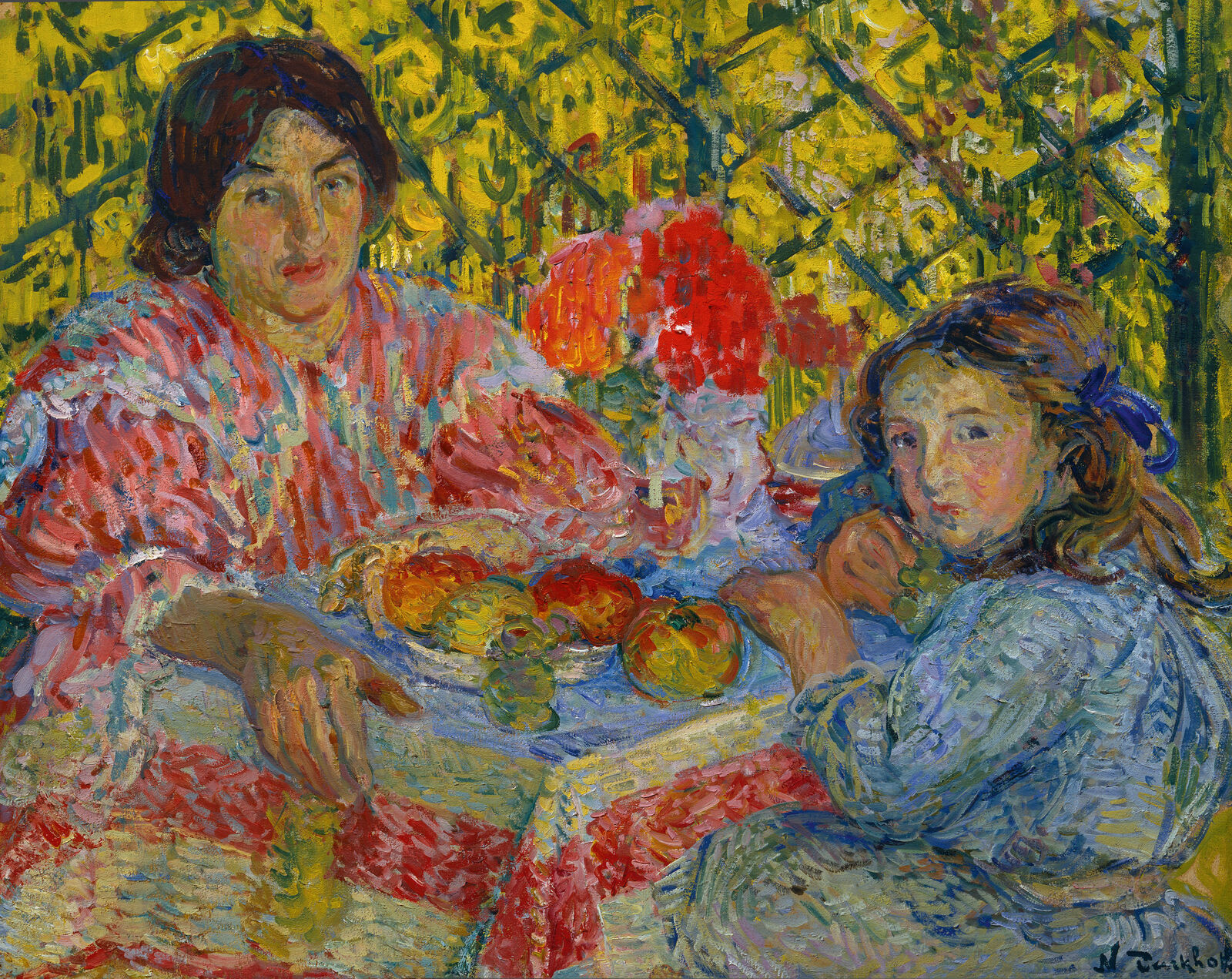

Nicolas Tarkhoff: Breakfast, 1906

State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

In the early 20th century, a new generation of Russian artists arrived in Paris. For them, color became a powerful new force.

Like the French Post-Impressionists and Fauves before them, they intensified their expressive capabilities by working in pure, glowing colors. Rich hues applied in strong brushstrokes gave their painting a luminosity never before seen in Russian art. Color acquired a significance of its own, independent of the depicted motif. These artists achieved recognition internationally as well.

It is time for us to quit chasing Parisian fashions … and develop our own character. May national pride, self-knowledge, and self-respect help us embrace the inexhaustible beauty of our homeland even more deeply in our hearts.

Vladimir Burliuk: Young Girl with Yellow Kerchief, 1906–07, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

In Young Girl with Yellow Kerchief, Vladimir Burliuk used Neo-Impressionist dots of paint to evoke a folkloric Russian motif. The young woman in a headscarf and apron looks like a traditional peasant, yet she appears not front of a farmhouse or in a rural landscape, but in a brightly lit studio. The use of the Pointillist painting technique in areas such as the colorful clothing transforms the time-honored motif and creates shimmering, modern chromatic effects.

The color red is predominant in all of Abram Arkhipov’s works. In Russia, red has special meaning: the Russian word for red—krasnaya—is etymologically related to the word krasny, or beautiful. In the icon painting of the Russian Orthodox Church, red signifies the divine, and in 1917 the Bolsheviks continued the tradition when they established a new visual culture under the banner of the red star.

Abram Arkhipov: The Visit, 1914, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Alexej von Jawlensky: Andrei and Katia, 1905, Collection of Iveta and Tamaz Manasherov, Moscow

Studies in Munich

While many Russian artists were drawn to Paris, the painting school of Anton Ažbe in Munich also emerged as an important destination for aspiring Russian painters. Ažbe taught his students, among them Alexej von Jawlensky and Vassily Kandinsky, to apply unmixed colors directly to the canvas. Previously, Jawlensky had studied with Repin in Russia; now, however, he embraced a palette of glowing colors. The faces of Andrei and Katia, painted with a light touch, already foreshadow Jawlensky’s Expressionist style.

Konstantin Korovin: Pond: Study, 1907, State Museum of Fine Arts of the Republic of Tatarstan, Kazan

Landscape painting was an entirely new genre in Russian art. Inspired by Impressionism, artists explored the countryside around Moscow and St. Petersburg, painting in the open air.

Many of them journeyed long distances, traveling to the northern reaches of Russia. Like their French counterparts, they used the expanding railway network to travel from the vibrant cities to the Russian countryside. Yet these artists were interested in more than just the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere; in nature, they sought the feeling, the subjective and poetic mood of the Russian landscape.

What a terrible mistake to chase after French color hues when there is so much beauty here.

Sergei Vinogradov: At a Country Estate in Autumn, 1907, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Peredvizhniki: The Wanderers

Abram Arkhipov, Valentin Serov, and Sergei Vinogradov were all members of the Peredvizhniki or “Wanderers,” the first independent artists’ association in Russia. This society for traveling exhibitions was formed in 1870 in protest against the strict dogmas of the Imperial Academy of the Arts in St. Petersburg. In their paintings, they depicted the life of the simple rural population. With the traveling exhibitions that gave the Peredvizhniki their name, these artists went into the Russian provinces, bringing their paintings to a broader public.

Sergei Vinogradov: In the House, 1912

State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Summer homes offered a refuge for carefree life in the country. The dacha—sometimes a lavish country estate, sometimes a simple wooden house—was more than a vacation home: it was a place for quiet, fresh air, and informal sociability.

At the dacha, the Moscow Impressionists painted interiors flooded with light. The effects of light on interior spaces and everyday objects also inspired these artists to paint still lifes, a genre that enjoyed little esteem at the Imperial Academy of the Arts and was considered unserious. The new Impressionist vision for the charm of the everyday, however, elicited new forms of painterly expression, free of weighty content and somber themes.

Konstantin Korovin: Tea on the Terrace, 1916, ABA Gallery, New York

Olga Rozanova: Flowers on the Windowsill, ca. 1910, Collection of Iveta and Tamaz Manasherov, Moscow

In addition to interiors, terrace scenes were also a popular motif at the dacha. Here, elements from different artistic genres—nature, still life, and genre scenes—could interact with one another. At the threshold between interior and exterior space, figures and objects fuse into a harmonious whole, flooded with light.

The artist must never passively imitate nature, but must become the active mouthpiece of his relationship to nature.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

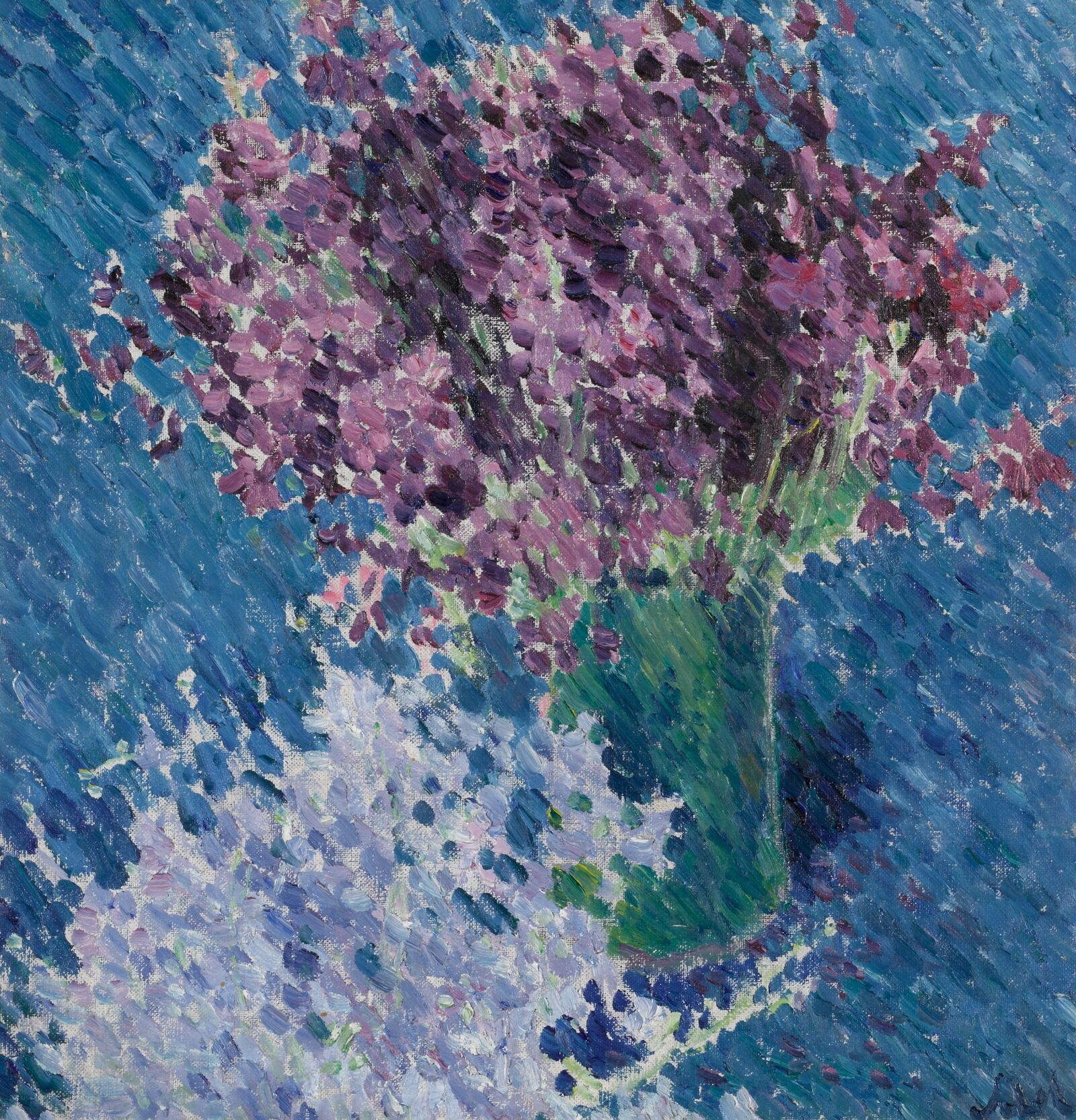

Mikhail Larionov: Lilac, 1904–05, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Mikhail Larionov was one of the most important artists of the early avant-garde, whose radical aesthetic paved the way for modernism in Russian art. His early career was decisively influenced by his encounter with Impressionism. He was particularly affected by the works of Claude Monet, whose painting Lilacs in the Sun he studied in the private collection of Sergei Shchukin.

Vladimir Baranov-Rossiné: Green Garden, 1907–08, Collection of Vladimir Tsarenkov, London

Experimentation with landscape encouraged Russian artists to embrace a new freedom in their painting. Rapid, impassioned brushstrokes become a vehicle of expression: the artistic handwriting of individual artists asserts itself independently of the motif. In their early, Impressionist-inspired works, the later pioneers of the Russian avant-garde freed themselves from the naturalistic Realism of the preceding generation.

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

Natalia Goncharova: Landscape (Pointillated), 1907–08, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

I have learned everything the West could give me … I am now shaking the dust from my feet and leaving the West … my path leads to the source of all art, the East.

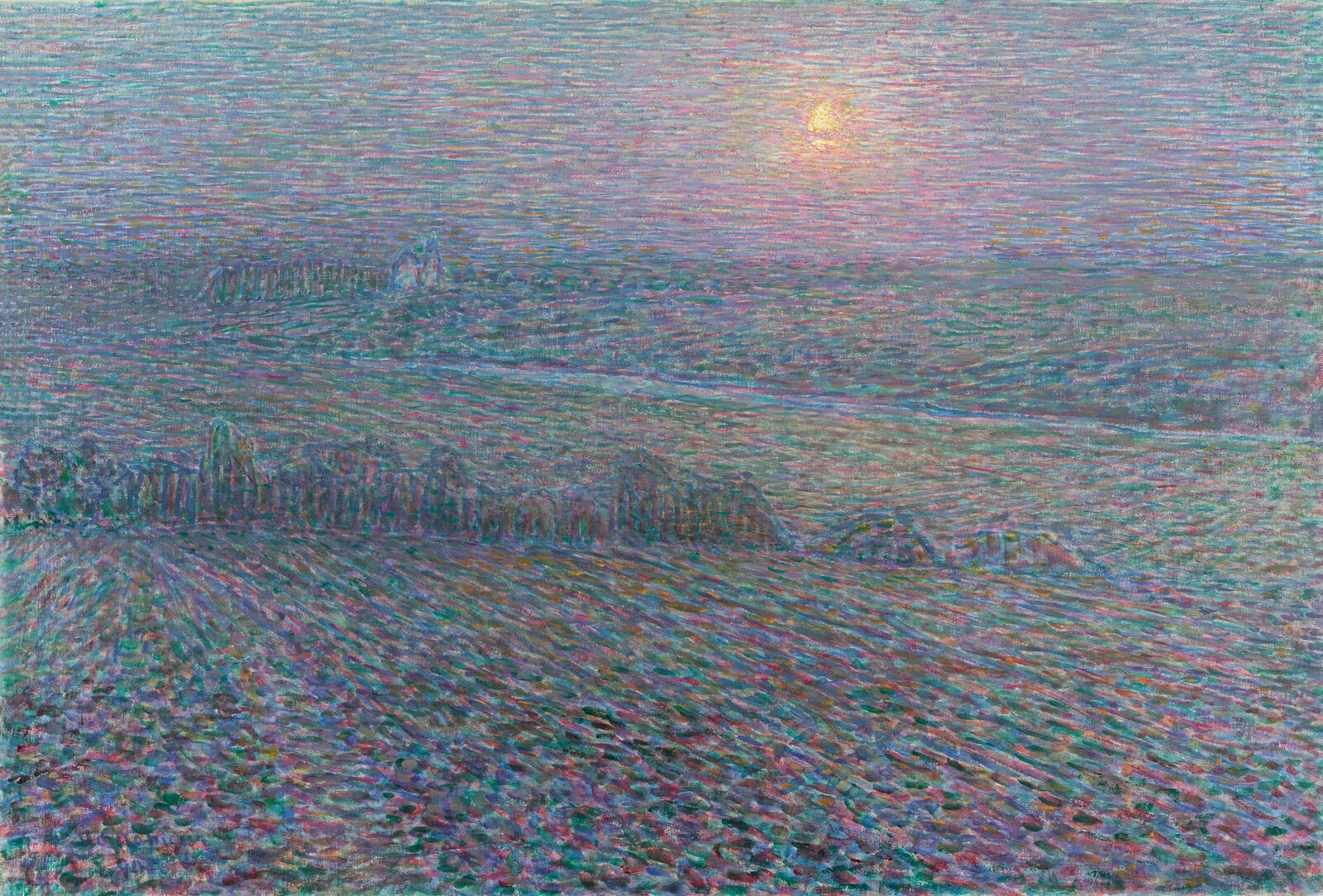

Nikolai Meshcherin: Moonlit Night, 1905, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The moon emits its radiance in a bright circle, surrounded by azure pearlescence. The clouds—gray masses on a veil of azure pearlescence. … Rose, purple, green in the distance.

Wintry landscapes with their effects of light had already captivated Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. Russian artists, too, were fascinated by snow-covered views of their homeland. For snow is not merely white: its surface can reflect all the colors.

Olga Rozanova: Corner of the House and Bullfinches in the Tree: Winter, 1907–08, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Robert Falk: Winter in Pokrov, 1905, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Winter, snow, and ice have long been important themes in Russian culture.

Father Frost, the personification of winter, gives gifts to children on New Year’s Eve. In his poetry, Alexander Pushkin wrote of the “fields adorned in powdery white” of his homeland, and from a historical perspective, the merciless Russian winter with its bone-chilling cold and masses of snow brought many an enemy army to its knees. For the painter, the charm of the Russian winter landscape lies precisely in the limitations of the motif. When snow covers everything, the effects of shadow and the winter sun appear all the more striking on the crystalline blanket of white.

Natalia Goncharova: The Rowers, 1912, Collection of Vladimir Tsarenkov, London

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

The artists of the Russian avant-garde developed a pioneering new visual language. In so doing, they reacted to the dynamism of a new era in which, after 1905, social conflicts in Russia led to revolutionary unrest.

At the same time, however, they embraced the Impressionist painting of light, which provided the point of departure for their radical innovations. In lively international exchange with Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism, they liberated the artistic power of light and color. Instead of observing light as a natural phenomenon as the Impressionists had done, these pioneers of the avant-garde made it an element of their non-objective world.

Color is also light, light is also color—depending on the circumstances

Georgy Iakulov: Bar, 1915, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

Mikhail Larionov: City at Night: A Rayonist Composition, 1912–14, Collection of Vladimir Tsarenkov, London

The painter Georgy Iakulow developed his own theory of light in painting. In his painting Bar of 1915, he shows a motif that had already fascinated the Impressionists: the leisure activities of the big city. In Paris he had encountered the artist couple Sonia and Robert Delaunay, whose intensely colored Orphism echoed his own artistic interests. The colorful dissection of the picture plane resembles the effect of a prism, refracting light into the colors of the spectrum.

In 1913, Goncharova and Larionov published the Rayonist Manifesto, which dealt with the fourth dimension of light. The entire picture field of the Rayonist composition City at Night is refracted into parallel planes resembling beams of light. Larionov’s abstract image evokes the throbbing dynamism of the city by night. He transforms the real, perceptual experience into a pure, pulsating realm of light and color.

I understood that Impressionism was concerned not with the precise rendering of appearances or objects, but exclusively with the way in which I turned my entire energy toward the purely painterly quality that these appearances conveyed or carried within themselves.

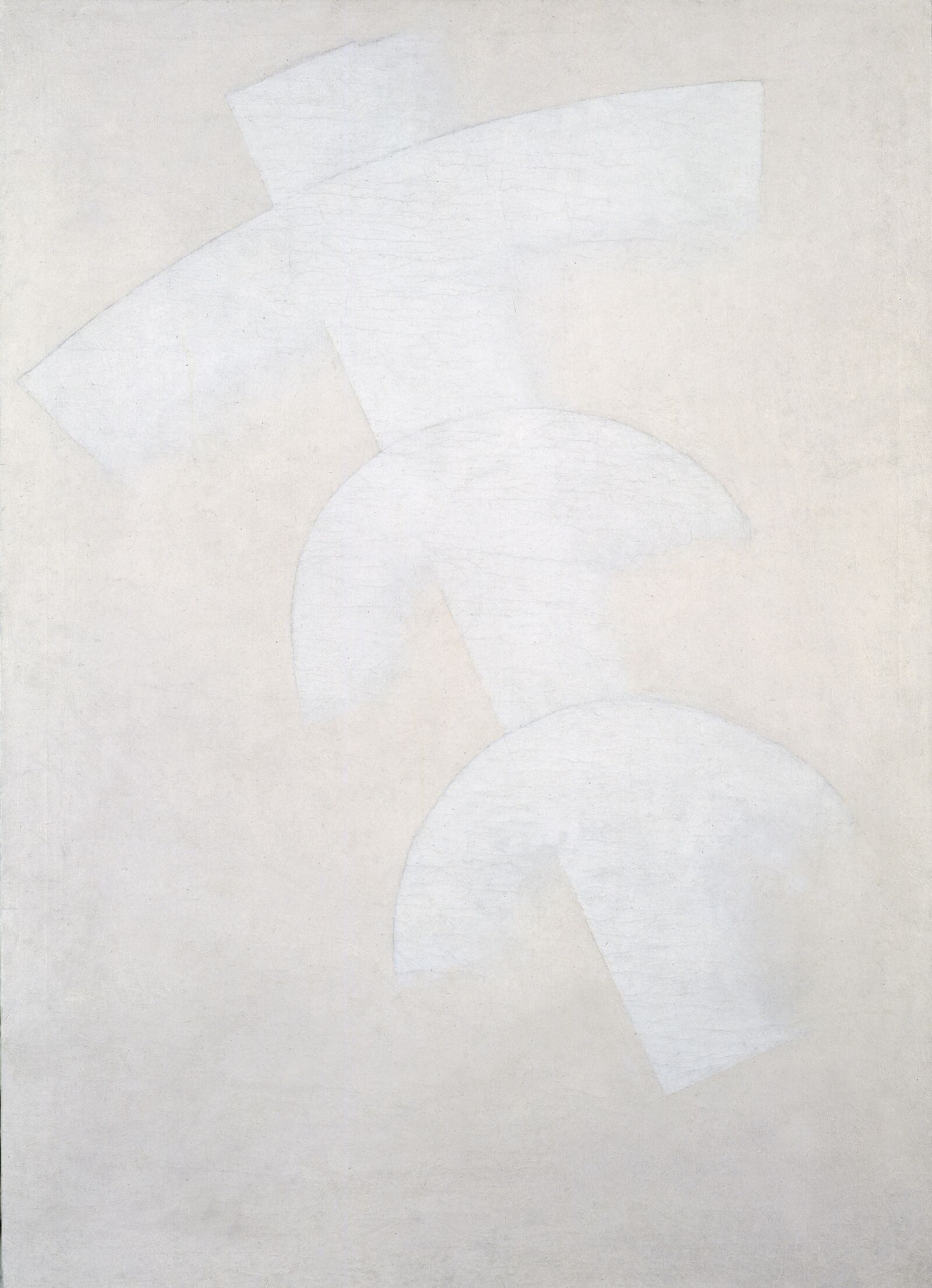

Kazimir Malevich: Construction in Dissolution (Three Arches on a Diagonal Element in White), 1917, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

In the years after 1915, Malevich searched for a non-objective style of painting able to convey pure feeling. In this phase, which he called Suprematism, he initially used black or colored forms floating in front of a white background. He viewed the series White on White as the conclusion of a development that had begun with Impressionism. In his painting Construction in Dissolution (Three Arches on a Diagonal Element in White), the all-encompassing white absorbs the forms, fusing together light and space.