Rembrandt’s Orient

Rembrandt and his contemporaries were fascinated by the distant lands from which imported goods flowed into the Netherlands in the 17th century. Turbans and carpets, sabers and silk—the enthusiasm for the foreign and the exotic became fashionable and gave rise to a new kind of art.

Over 100 Masterpieces

Biblical scenes, portraits, and still lifes combined realistic motifs with idealized images and fantastical projections. The darker aspects of this development, however—the imbalance of power between cultures, as well as slavery, violence, exploitation, and trade wars—were not represented.

With over 100 masterpieces by Rembrandt, Jan Lievens, Ferdinand Bol, Willem Kalf, and other contemporaries, the exhibition explores images and ideas of the foreign from their time. West and East, however, did not always meet on equal footing: while the Dutch appreciated exotic objects and integrated them into their lifestyle, they were less interested in learning about foreign peoples and cultures than in appropriating this new store of motifs with their accompanying prestige. In Rembrandt’s day, the term “Orient” was geographical and referred to the eastern Mediterranean and Asia; today, however, it carries a negative connotation, since the “Orientalism” to which it gave rise asserted the superiority of the West over the Arab world. The title of the exhibition, Rembrandt’s Orient, signals the intent to explore the views and perspectives of Rembrandt’s day.

This prolog to the exhibition explores the ideas these artists associated with the “Orient” and examines the influence of foreign cultures on their work. In addition, both the prolog and the accompanying program offer the opportunity to interrogate the Eurocentric clichés and stereotypes that still shape our image of the world today.

Jacob van Hasselt (?): The Wedding Feast of Grietje Hermans van Hasselt and Jochum Berntsen van Haecken, 1636, Centraal Museum Utrecht

The expansion of trade to other continents brought enormous prosperity to the citizens of the Dutch Republic. Exotic goods poured into the country; knowledge of foreign lands increased.

Although travel to faraway places was possible only for a few, such journeys were by no means prerequisite for exposure to oriental influences. The availability of exotic objects altered habits of life and fashion—and impacted painting as well. Genre scenes and portraits (portraits historiés) incorporated motifs from Asian cultures, presenting them as status symbols.

Dirck van Loonen: Assueer Jacob Schimmelpenninck van der Oye (1631–1673) with Servant and Dog, 1660, Stichting Duivenvoorde, Voorschoten

After his return from a year-long pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Damascus, and Aleppo, Assueer Jacob Schimmelpenninck commissioned a portrait of himself in proud oriental splendor, displaying his magnificent souvenirs. With his caftan, saber, and feathered turban, he almost seems to play the role of a sultan; the massive dog, too, was a souvenir of his journey and an impressive status symbol. Schimmelpenninck’s travel diary, however, reveals that during his time abroad, he primarily associated with expatriate countrymen or Western merchants. Although he occasionally mentions local customs, for the most part he shows little interest in the cultures he was experiencing.

Whether painter, scholar, merchant, or trade governor—to pose for a portrait in oriental costume was “in.”

Such representations bore witness to urbanity and open-mindedness. A favorite garment was the silk japonse rok, a Japanese dressing gown. A Persian carpet casually included in the picture likewise served as a prestige object; instead of being placed on the floor, it was demonstratively spread out on the table.

Aelbert Gerritsz. Cuyp: Group Portrait of the Sam Family, ca. 1653, Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

In Aelbert Cuyp’s Group Portrait of the Sam Family, some figures are clad in brightly colored tunics and silk garments, while others wear the plain black and white more typical of the Calvinist Netherlands. Were such costumes meant to convey a deeper significance? At times, Dutch couples and families enjoyed presenting themselves in role portraits with religious references—for example as Old Testament characters, identifiable by their clothing from the East.

Claes Jansz. Visscher II. and Pieter Bast: View of Amsterdam, Seen from the IJ, 1611, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The global trade networks developed by the Dutch in the 17th century formed the basis of their interest in faraway lands.

Visual representations of commercial activities were not intended to accurately represent scenes from everyday life or historical events; rather, they were intended to convey prestige or fulfill a decorative function. The same was true even for the depiction of ongoing military conflicts. The darker aspects of the Dutch overseas trade, such as the slavery, violence, exploitation, and oppression that helped secure the wealth of the Dutch Republic, were not represented by artists.

On board they had 400 loads of pepper and 100 loads of cloves, as well as mace, nuts, nutmeg and cinnamon, porcelain, silk and silk cloth, and other treasures

Gerrit Adriaensz Berckheyde: The Town Hall on Dam Square in Amsterdam, 1672, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The bustling crowd in front of the newly built Amsterdam town hall in the painting by Berrit Adriaensz. Berckheyde includes several men in turbans—a subtle nod to the regular presence of visitors from non-European cultures. This anecdotal detail may even have reflected a real experience. Rembrandt, too—who never traveled outside the Netherlands—might have seen and sketched turbaned men in the same location.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn: Group of Men in Oriental Apparel and Two Half-Length Studies of a Beggar, ca. 1641–42, University of Warsaw Library

Where else on earth could you find, as easily as you do here, all the conveniences of life and all the curiosities you could hope to see?

Johannes Lingelbach: A Sea Battle between Christians and Turks, ca. 1670 – 74, York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)

Jacques Muller: A Cavalry Encounter between Turkish Troops and the Troops of the Habsburg Empire, ca. 1645 – 73, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Dark storm clouds, flags flapping in the wind: images of military conflict on land or at sea pull out all the artistic stops to intensify the drama in detail—as well as to idealize it. Like its competitors, the Dutch East India Company was ruthless in the pursuit of its economic interests and found itself embroiled in ongoing armed conflicts with commercial and political powers such as Portugal, Spain, England, and the Ottoman Empire. Specific historical battles, on the other hand, were seldom depicted by Dutch artists.

Jan Lievens: The Feast of Esther, ca. 1625, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh

Very few Netherlanders had seen the lands of the East with their own eyes; for them, the Orient was first and foremost the setting for biblical events.

Rembrandt and his fellow painters showed stories from the Old and New Testaments in rocky landscapes very different from the flat, green countryside of the Netherlands. Their pictures feature turbaned men and women in splendid, imaginary costumes, although the colors and patterns of the shimmering silk fabrics may have been inspired by real imported goods.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn: David with the Head of Goliath before Saul, 1627, Kunstmuseum Basel

In his early twenties, Rembrandt painted the Old Testament story of the encounter between the boy David and the majestically clothed King Saul. He depicted the Israelite king as an oriental sultan in a white turban and yellow-gold mantle. In Rembrandt’s day, history painting was considered the highest genre of art, and also included stories from the Bible, which the young Rembrandt successfully dramatized in brilliant color.

Do you wish to show the Turkish sultan in all his splendor? Then paint him in white satin or silver fabric. ... Put a tall turban with painted feathers on his head.

Artists chose stories from the Old Testament that were exciting and full of emotion. Comprehensible to Christians of all confessions, they were also suitable as models for a virtuous life. For educated viewers, oriental settings offered a reflection of their own desires and weaknesses.

Jan Victors: The Angel Taking Leave of Tobit and His Family, 1651, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Just as Dutch meals in the 17th century were enhanced with foreign spices like pepper, cinnamon, and nutmeg, so too artists adorned their history paintings with exotic set pieces. Bartholomeus Breenbergh’s brightly colored painting Joseph Distributing Corn in Egypt brings together light and dark-skinned figures and combines borrowings from the Orient with Roman architectural elements.

Bartholomeus Breenbergh: Joseph Distributing Corn in Egypt, 1655, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham

Jan van der Heyden: Room Corner with Curiosities, 1712, Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

The increase in knowledge of faraway lands gave rise to a plethora of new books and maps. Amsterdam became a center of publishing.

Portraits of scholars with open books embodied the ideal of education. Seashells and other precious objects found their way into bourgeois homes as coveted collector’s items, and the fascination with the exotic was reflected in still lifes and interiors. Interest in the foreign was wide-ranging, but generally superficial; personal exchange between scholars from different countries, for example, is documented in only a few cases.

Willem Kalf: Pronkstilleven, 1678, Statens Museum for Kunst––National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen

Willem Kalf’s Pronkstilleven celebrates the ownership of costly, foreign items. The commodities brought to the Netherlands included not only spices, fabrics, porcelain, and rugs, but also exotic objects desirable not for their utility, but for their beauty and singularity. In many still life paintings, a chambered nautilus shell occupies the place of honor. Like noblemen of the past, prosperous citizens of the Netherlands collected these rarities in so-called “chambers of curiosities” (Kunstkammern or Wunderkammern).

Following his curiosity, for forty years he took pleasure in collecting shells and minerals according to their kinds, which arrived on all the ships from Italy and other parts of the world. He assembled a fascinating cabinet.

Jacob van Meurs and workshop: Mandarin Insignia, 1670, University of Amsterdam

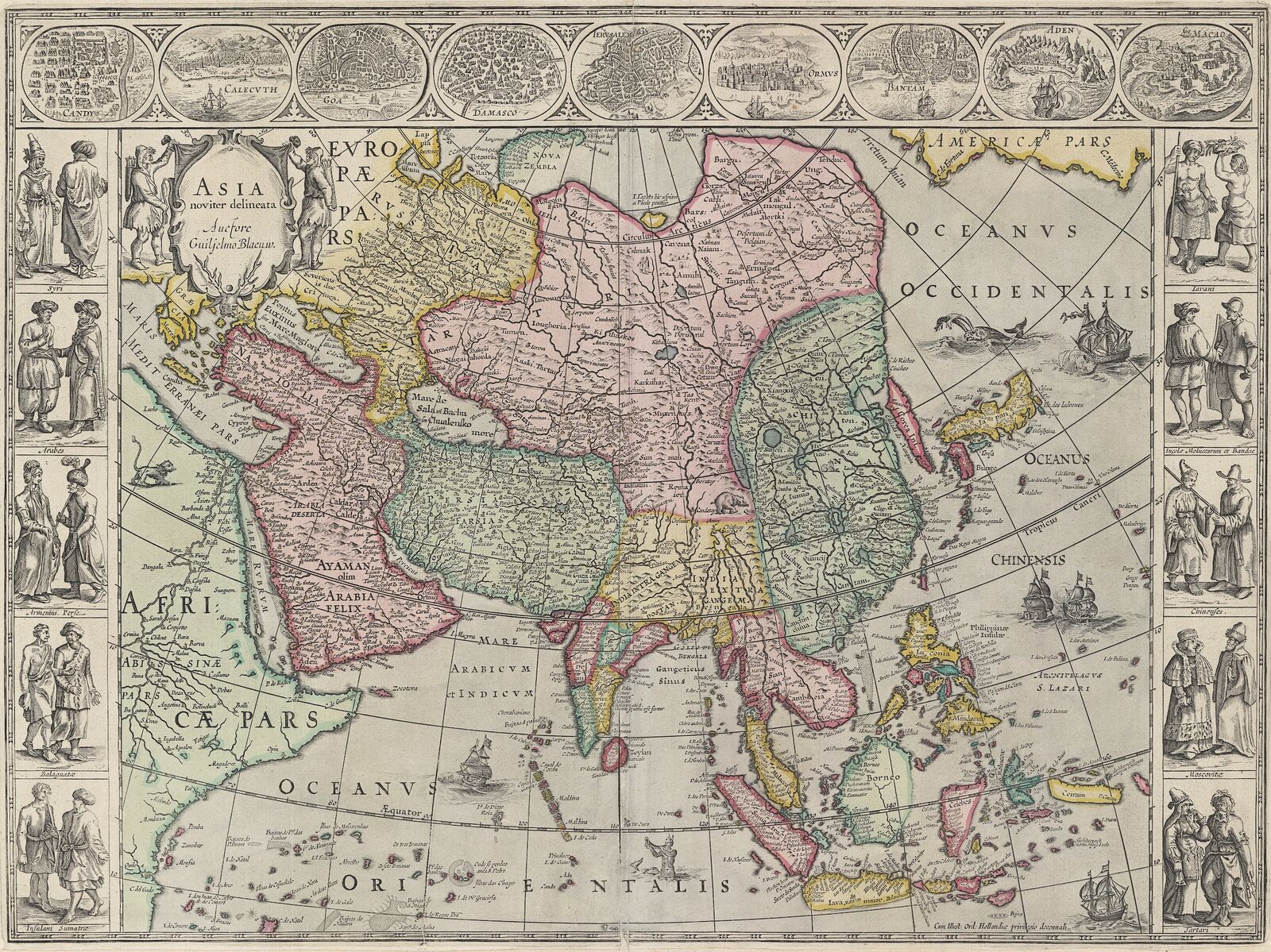

Willem Jansz Blaeu: Asia noviter delineata, ca. 1630, University of Amsterdam

Exploration of the world gave rise not only to enthusiastic collecting and research, but also to cartography.

For the Netherlands—a global trading power with overseas colonies—cartography had practical value, and the Dutch were the world’s leading mapmakers in the 17th century. Willem Jansz. Blaeu published an atlas with over 200 maps which, in keeping with Baroque taste, were adorned with decorative embellishments.

Portraits of scholars in the 17th century show them with massive tomes, symbolizing research and the acquisition of knowledge. In the economically thriving country of Holland, however, such volumes could also represent business or tax books. The portrait by Michiel van Musscher depicts Barend van Lin, who earned his money as a tax collector, cartographer, and surveyor. The astronomical model brought the cosmos directly into his study in Amsterdam.

Michiel van Musscher: Barend van Lin with His Younger Brother and His Future Brother-in-Law, 1671, Amsterdam Museum

J. F. F. nach Andries Beeckman: The Marketplace of Batavia, after 1688, Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam

Where is the line between documentation and artistic imagination? Landscapes and portraits may have seemed to depict real places and persons.

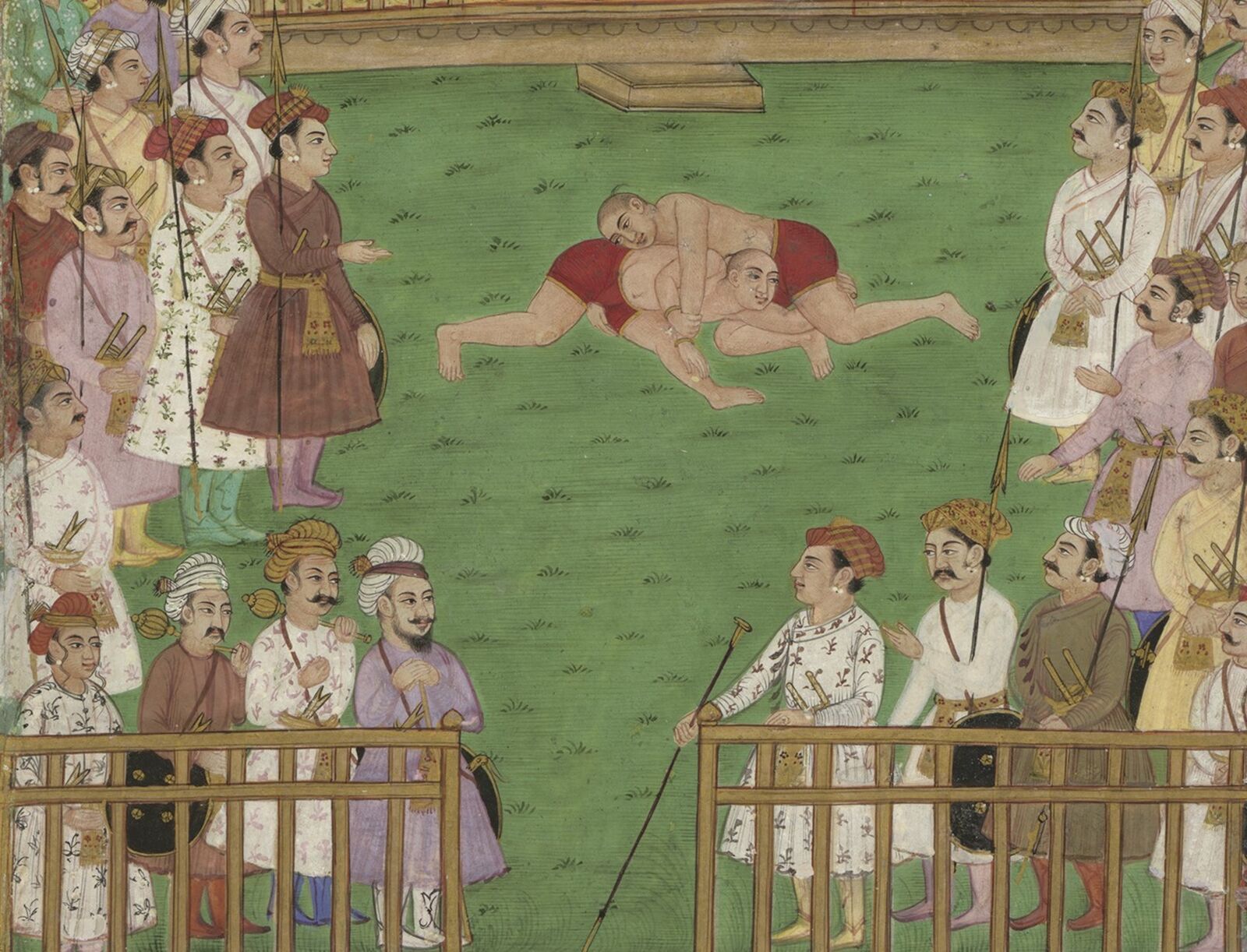

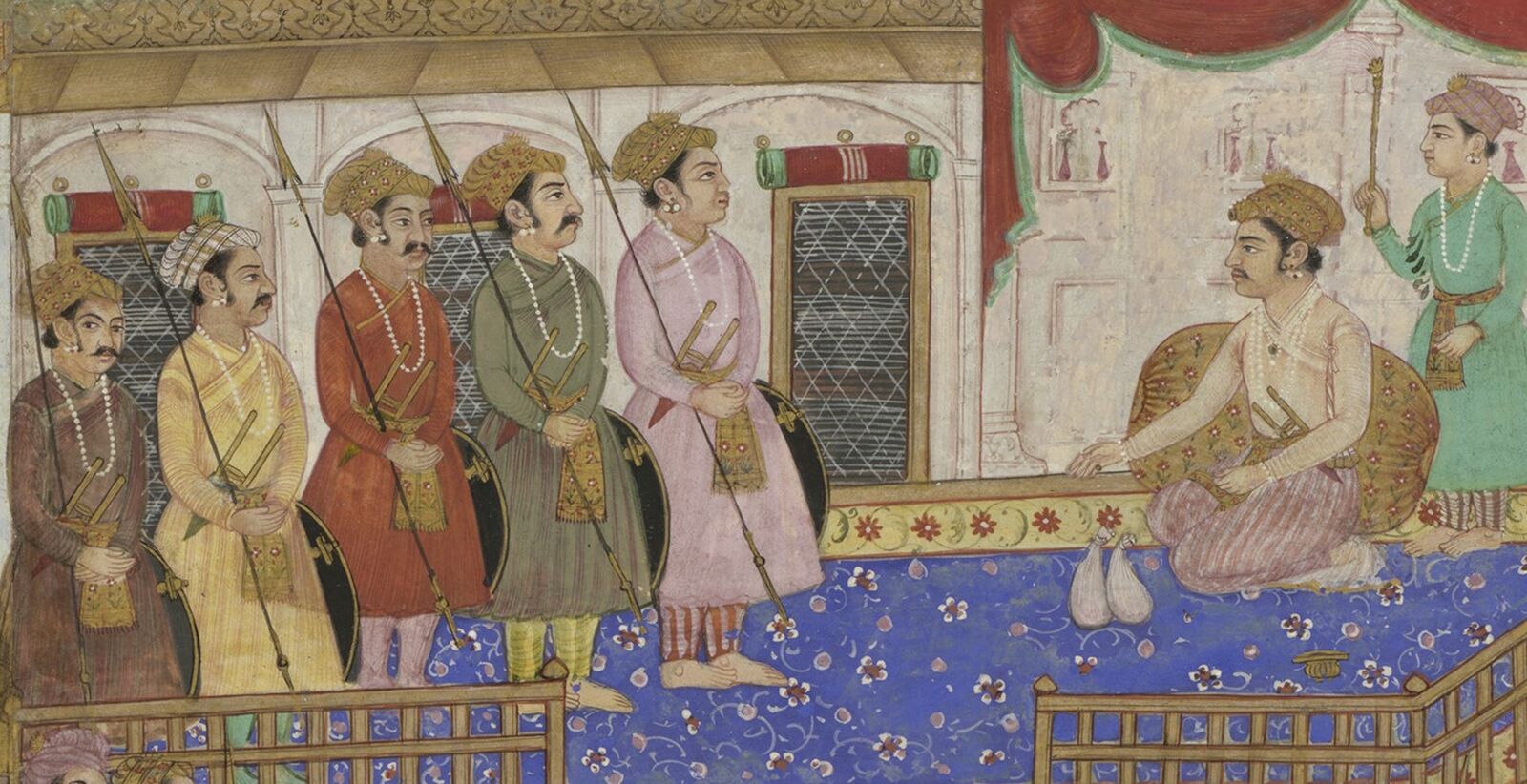

In the 17th-century Netherlands, however, only a few paintings showed reliable representations of faraway lands and their inhabitants. Many images simply confirmed existing clichés. In only a few cases did artists, including Rembrandt, study works of art such as miniatures from India or Persia.

We discovered in them the most secret peculiarities of the stories, way of life, and religion of the land.

The painter Willem Schellinks never traveled to India. Nevertheless, he is known to have studied a number of original Mughal miniatures, works which seldom found their way to the Netherlands. They filled him with enthusiasm and inspired him to create his own fantastical works such as the Parade of the Sons of Shah Jahan on Composite Horses and Elephants. No other Dutch artist of the period adapted Asian art as thoroughly as he did.

Willem Schellinks: Parade of the Sons of Shah Jahan on Composite Horses and Elephants, ca. 1665 – 70, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

... as exceedingly noble as an artist’s brush could ever paint

Hans de Jode: View of the Tip of the Seraglio with Topkapı Palace, 1659, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna

The view across the Golden Horn shows the promontory of the Seraglio Point in Constantinople, or modern-day Istanbul. It is unknown whether the painter Hans de Jode ever visited this site. His View of the Tip of the Seraglio with Topkapı Palace from 1659 could just as easily have been based on engraved scenes. In the 17th century, most of the painting’s viewers had likely never been to the Bosphorus and would thus be unable to evaluate the authenticity of the depiction.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn and workshop: Samson Threatening His Father-in-Law, ca. 1635, Natan Saban Collection, Israel

Whether palaces, temples, or the stall of Bethlehem—in the 1630s, Rembrandt and his fellow painters often showed biblical scenes in mysterious, dimly lit interiors.

Exotic turbans, robes, and swords helped lend authenticity to the depictions. This imagined Orient thus became a mystical site where the wisdom of God was revealed to the Israelites or the miracle of Christian salvation was accomplished. Nuanced effects of lighting dramatized the action and intensified its significance.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn: Samson Proposing the Riddle at the Wedding Feast, 1638, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

In his painting Samson Proposing the Riddle at the Wedding Feast, Rembrandt positions the brightly illuminated figure of the young bride at the center of the festive gathering: it is she who will disclose the riddle’s answer to the guests. In Rembrandt’s day, the orientalizing trappings of the scene were perceived by his contemporaries as exceedingly authentic.

Once I saw a picture of Samson’s wedding by Rembrandt... In it, one can see ... the guests sitting at the table—or rather reclining, for the ancients used beds, and lay on them ... as is still practiced in these lands among the Turks.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn and workshop (?): The Circumcision of Christ, ca. 1646 or later, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn: Daniel and Cyrus before the Idol Bel, 1633, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The exotic atmosphere of Rembrandt’s dark interiors differed markedly from the Protestant churches of the Calvinist Netherlands. The latter were light-filled, whitewashed, and lacked pictorial decoration. In contrast, the paintings of Rembrandt and his contemporaries evoked a mystical, exotic atmosphere imbued with a sense of the marvelous. The contrast with the everyday environment probably intensified the sensual fascination of such works.

Deep shadows and theatrical light: Rembrandt developed his dramatic chiaroscuro in the medium of printmaking as well. The scenes come alive solely in black and white, without the use of color. Turbans and tunics intensify the mysterious foreign atmosphere, while architectural settings are often only suggested. Prints like these, executed with the etching needle, were more affordable than oil paintings. Produced in large editions, they were widely disseminated and achieved considerable fame.

Ferdinand Bol: Portrait of an Oriental, ca. 1665, Milwaukee Art Museum

For the 17th-century Dutch, the Orient was the Other—an abstraction of the possible and a projection field for longings that had no place in the rationalistic worldview of the West.

This imaginary role-playing with the exotic also gave rise to a new pictorial type. In the late 1620s, the Tronie emerged: portrait studies of mostly anonymous persons with pronounced facial features, wearing splendid robes and often turbans.

In the house of my prince there is a portrait [by Jan Lievens] of a so-called Turkish prince, which was painted after the head of some Dutchman or other.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn and workshop: A Tronie of a Bearded Old Man in Middle Eastern Dress, ca. 1635, Lent by the Earl of Derby

Rembrandt frequently painted not only his models, but also himself, in a wide variety of costumes and roles. For this purpose he made use of a large collection of props, headdresses, and even weapons he had assembled over the years. Character heads (Tronies) of this type play with the ambivalence of appearance and reality—and indulge in the luxury of orientalizing robes. The opulent splendor and exoticism gives expression to a longing for the extraordinary and exceptional.