Modigliani

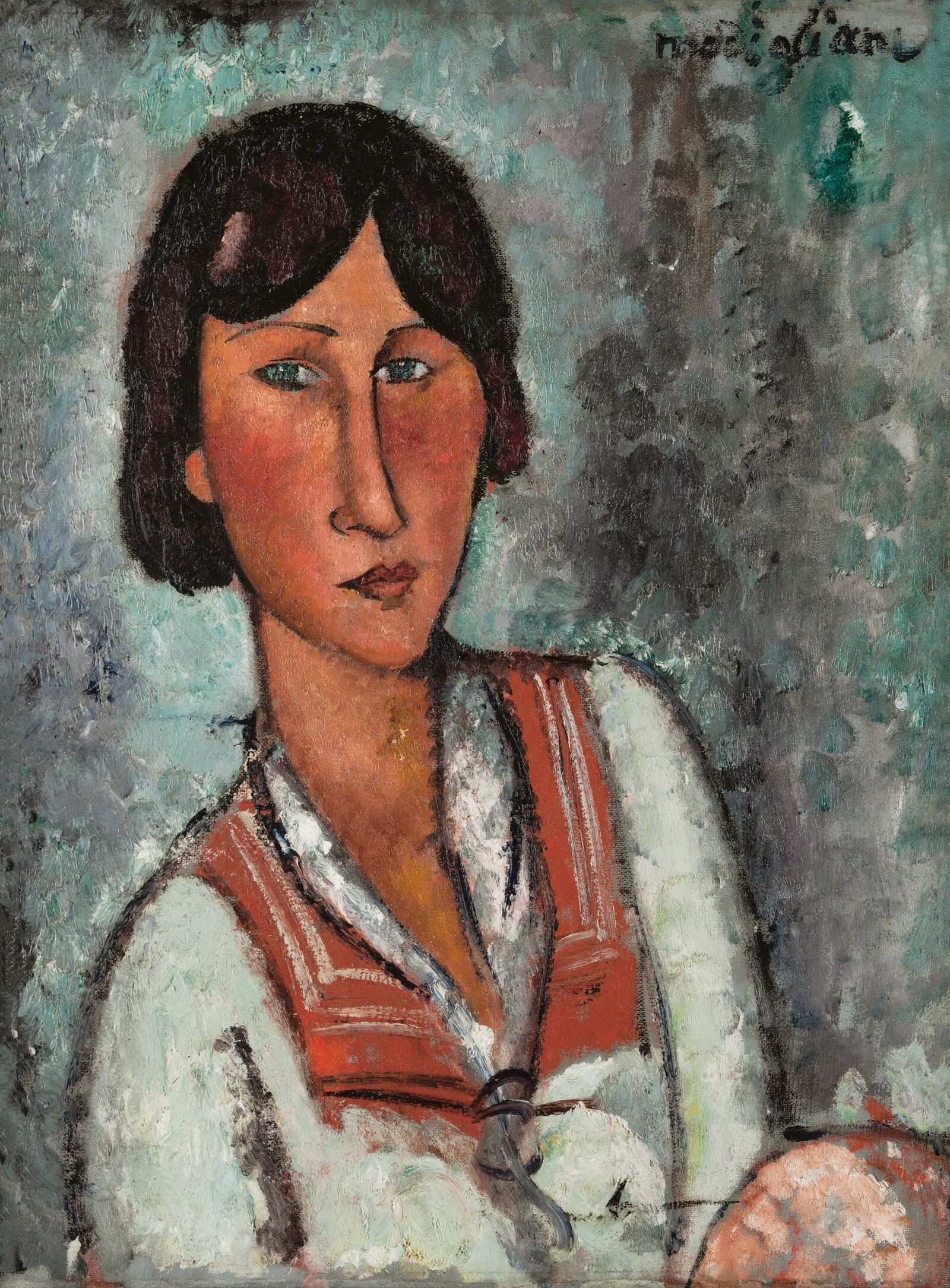

Who can resist these women? They confront us with a look that is both self-confident and introspective. Amedeo Modigliani allows them to define their own space; at times they appear charming, at times curious and impertinent — and often pensive as well. The nudes seem casual and relaxed, as if posing naked were the most ordinary thing in the world. The women Modigliani portrays on the canvas seem astonishingly modern: even today, most of them would hardly be out of place at either the supermarket or the gym — and not because they are unremarkable. On the contrary: their short hair and androgynous appearance fit perfectly into our era.

What I look for is neither reality nor unreality but the subconscious, the instinctive mystery of the human race.

Amedeo Modigliani: Portrait of a Woman, 1918, Denver Art Museum Collection, The Charles Francis Hendrie Memorial Collection

The middy blouse was a popular item of clothing among bohemian women artists, as photos of Modigliani’s circle of friends show. It was worn by figures like Nina Hamnett, who claimed to have performed sea shanties in the pubs of Montparnasse.

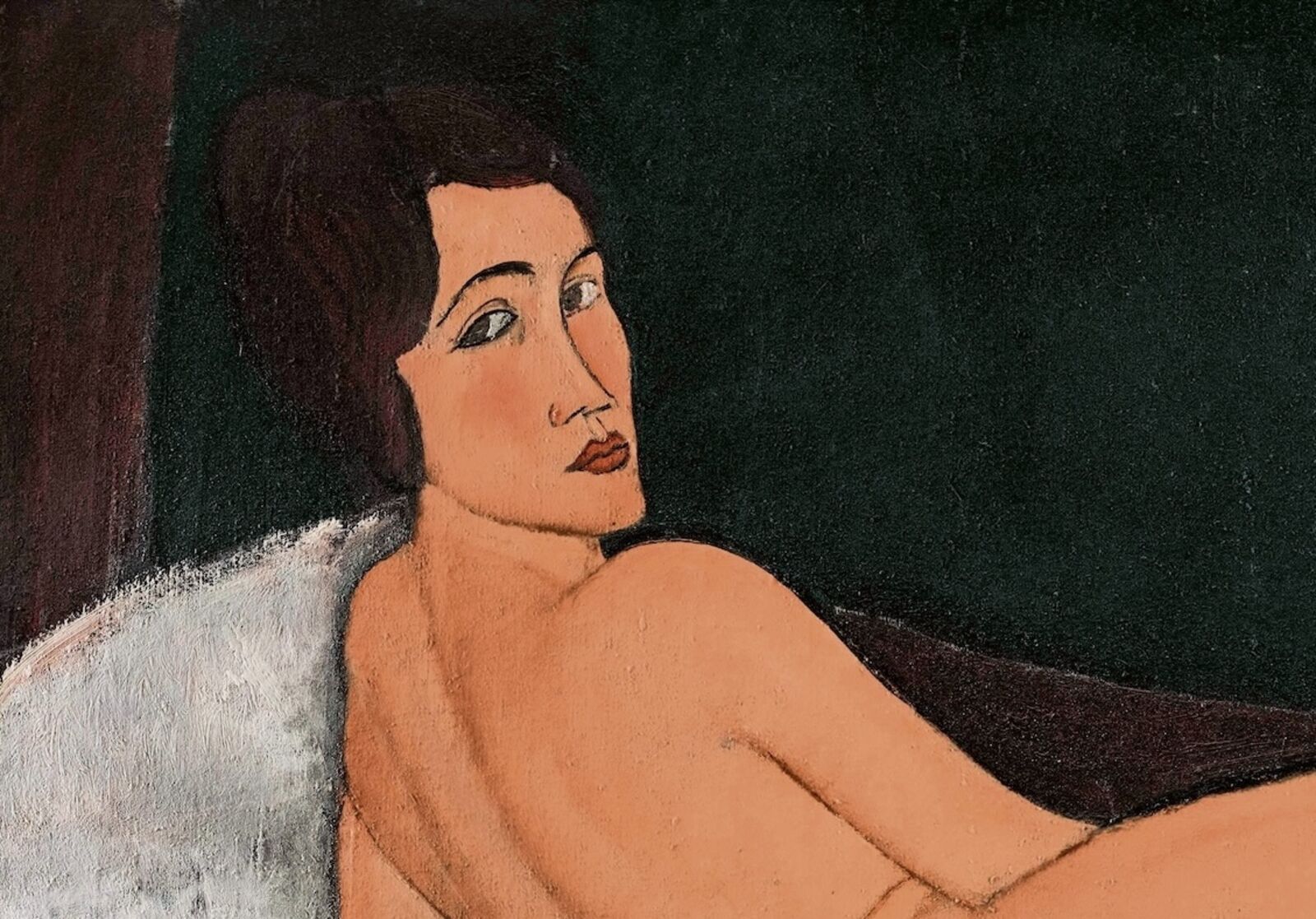

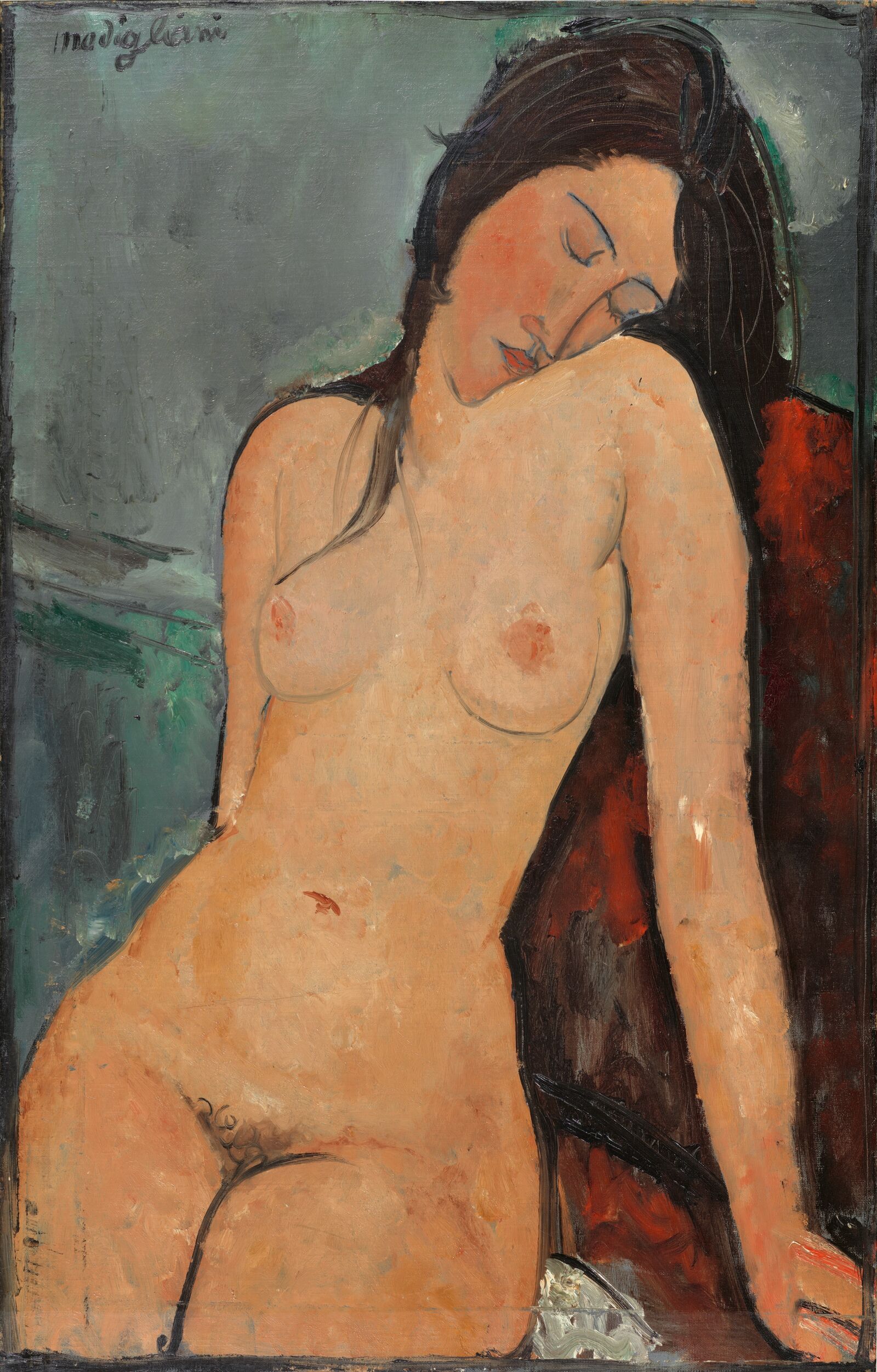

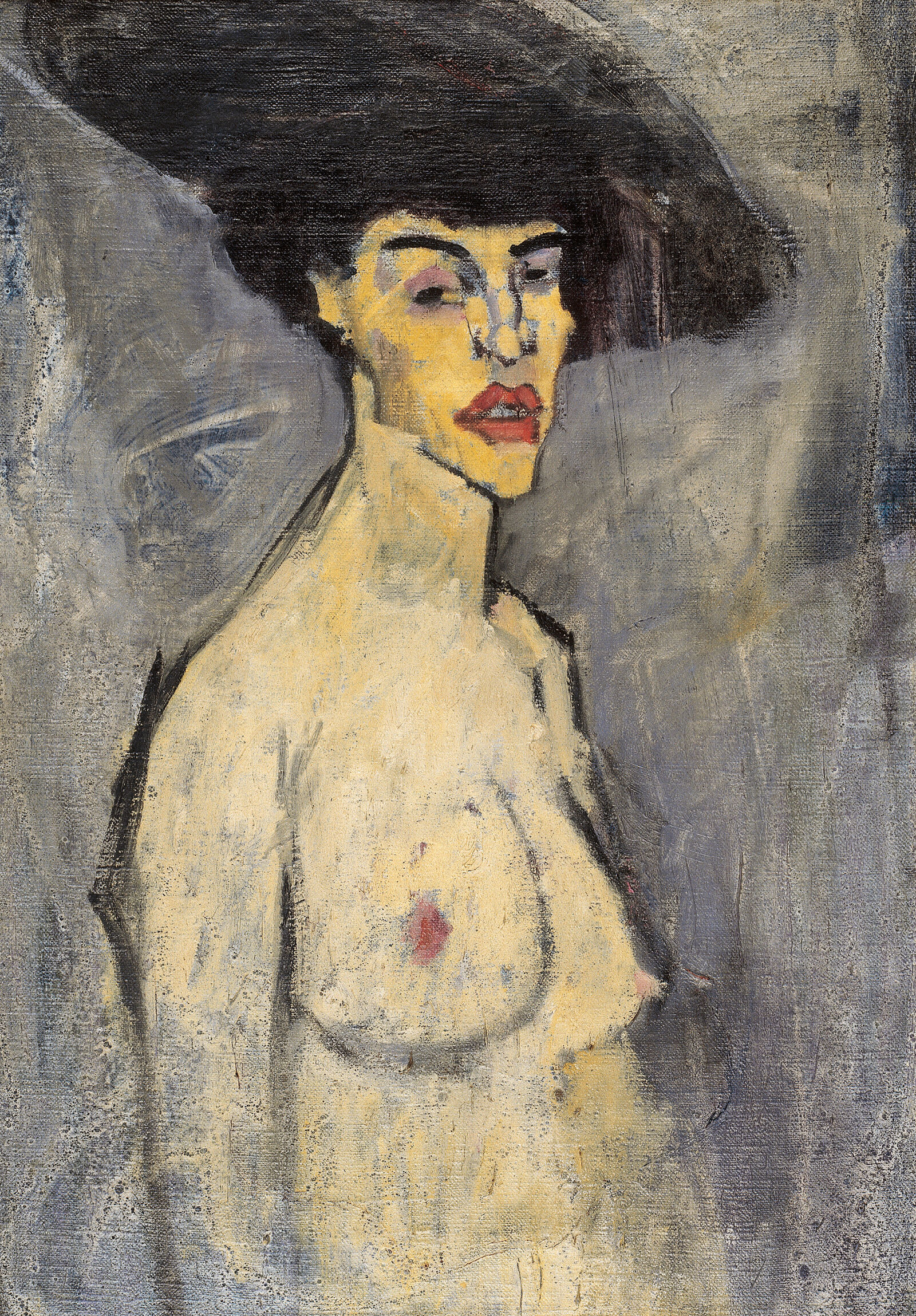

Amedeo Modigliani: Seated Nude, 1916, The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)

Photo: The Courtauld / Bridgeman Images

This Seated Nude was one of the first in Amedeo Modigliani’s series of nude paintings. The sitter seems modern and unpretentious: a new ideal of beauty.

The exhibition Modigliani: Modern Gazes also corrects the image of Modigliani as a perpetually intoxicated artist attracted only to mute stereotypes, as well as the myth of the egomaniacal womanizer who drove his pregnant mistress to suicide with his early death from tuberculosis. In reality, Amedeo Modigliani treated women with considerable respect and could even be described as an early feminist. The exhibition project, conceived in cooperation with the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, looks beyond the milieu of Paris and Montmartre to show Modigliani in a European context alongside artists like Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Paula Modersohn-Becker, and Wilhelm Lehmbruck.

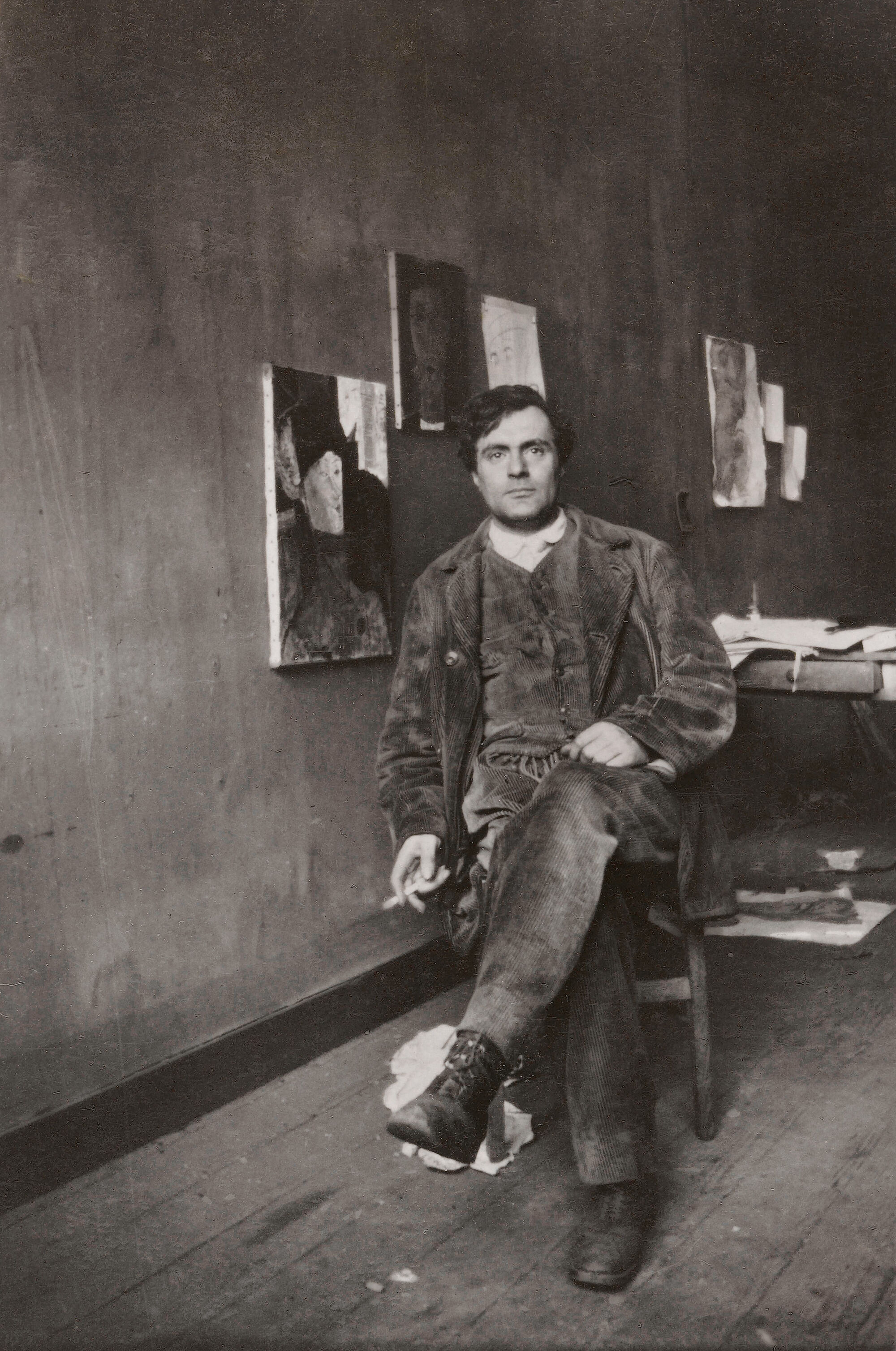

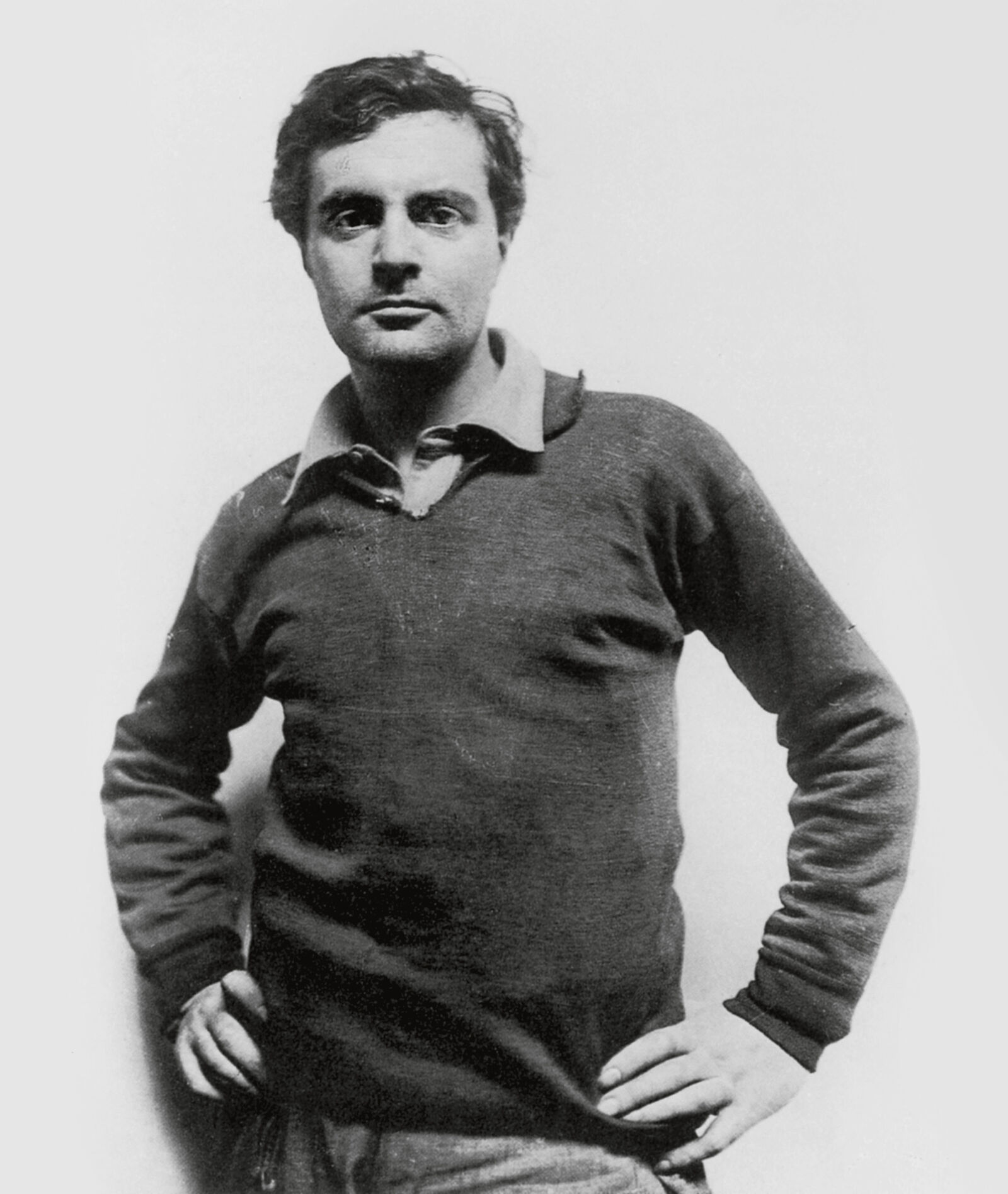

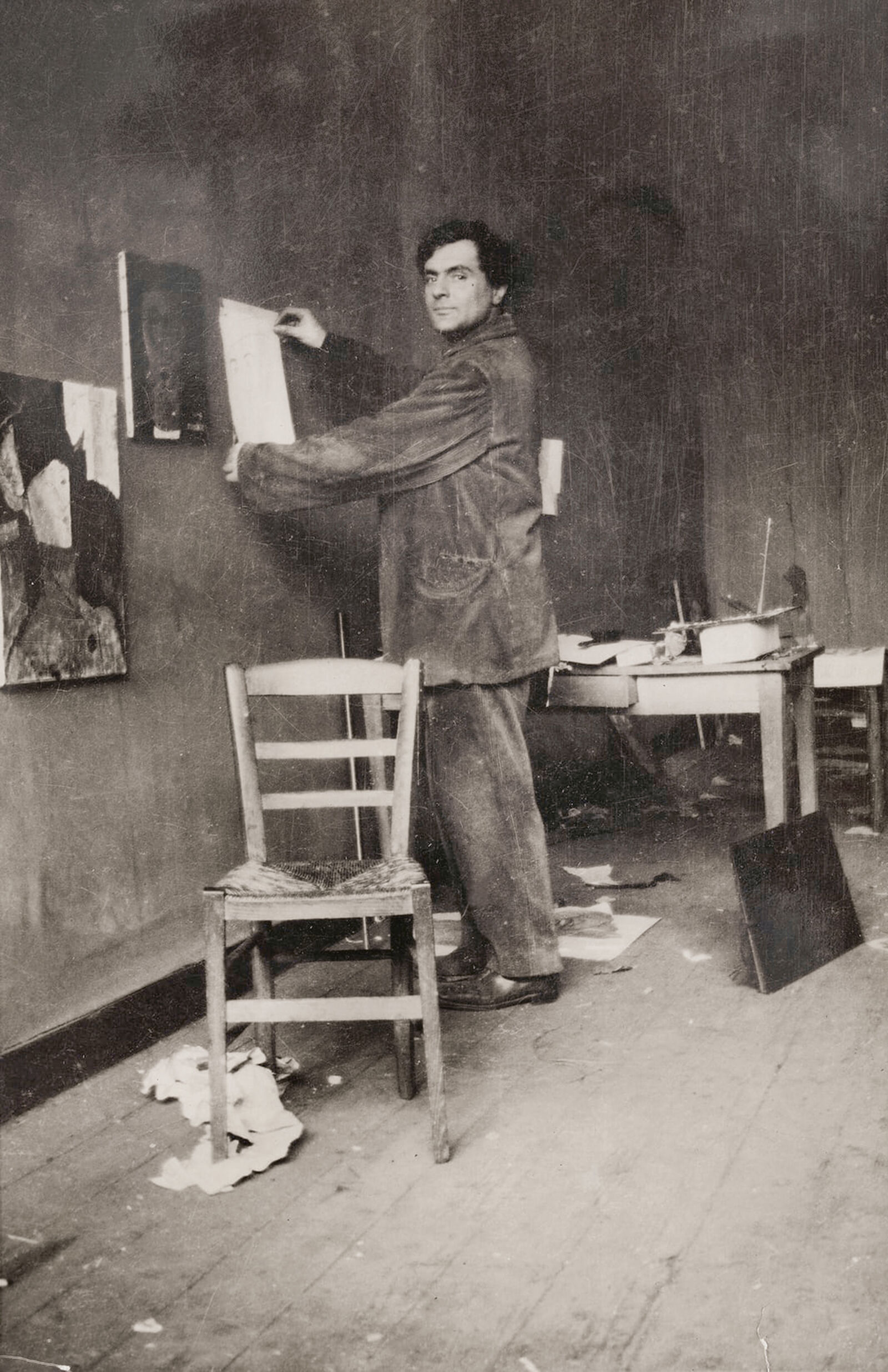

Anonym: Amedeo Modigliani, ca. 1919

Amedeo Modigliani, ca. 1919

Modigliani loved poetry and judged ... with spirit and a mysterious sensitivity to the subtle and the adventurous.

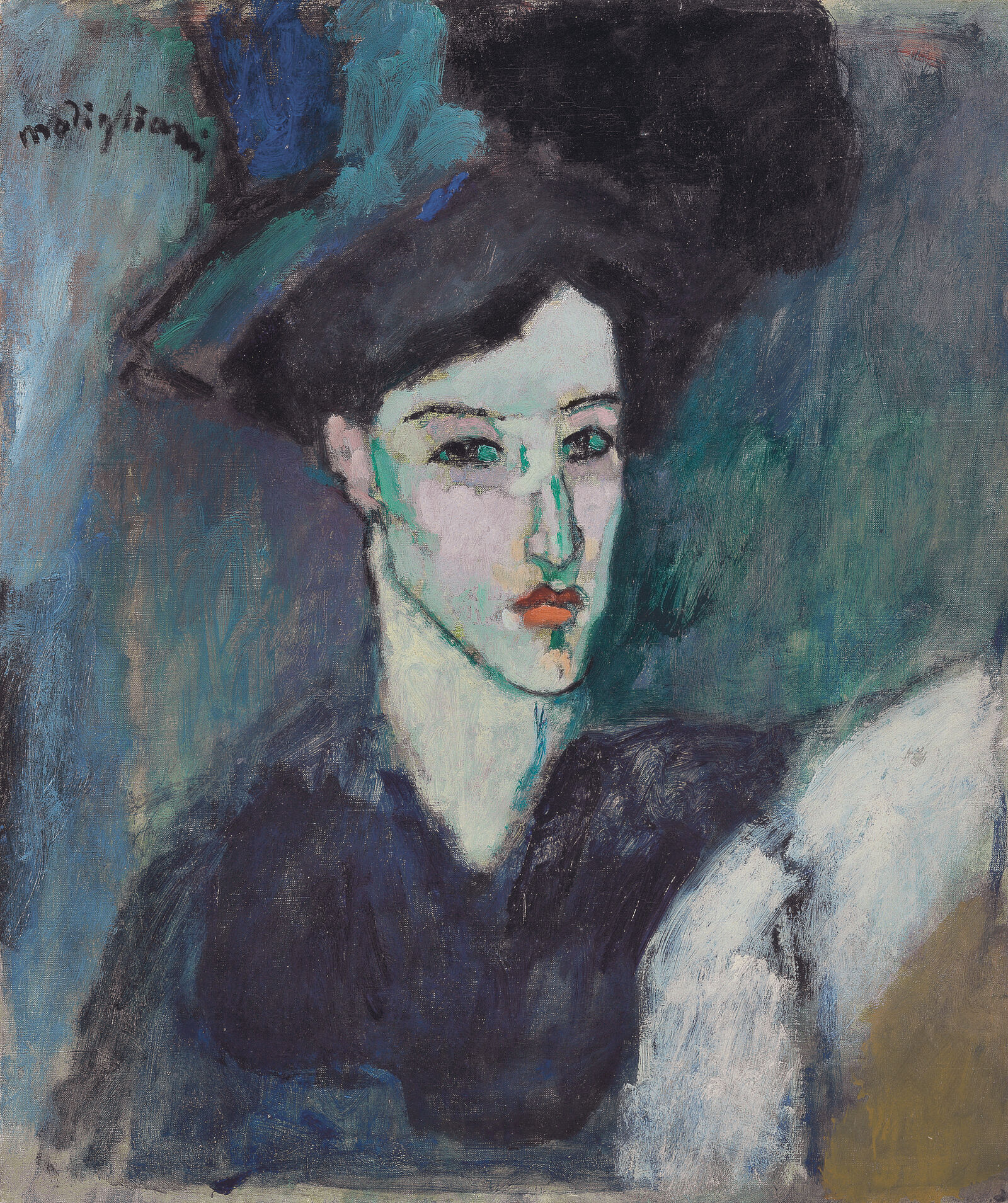

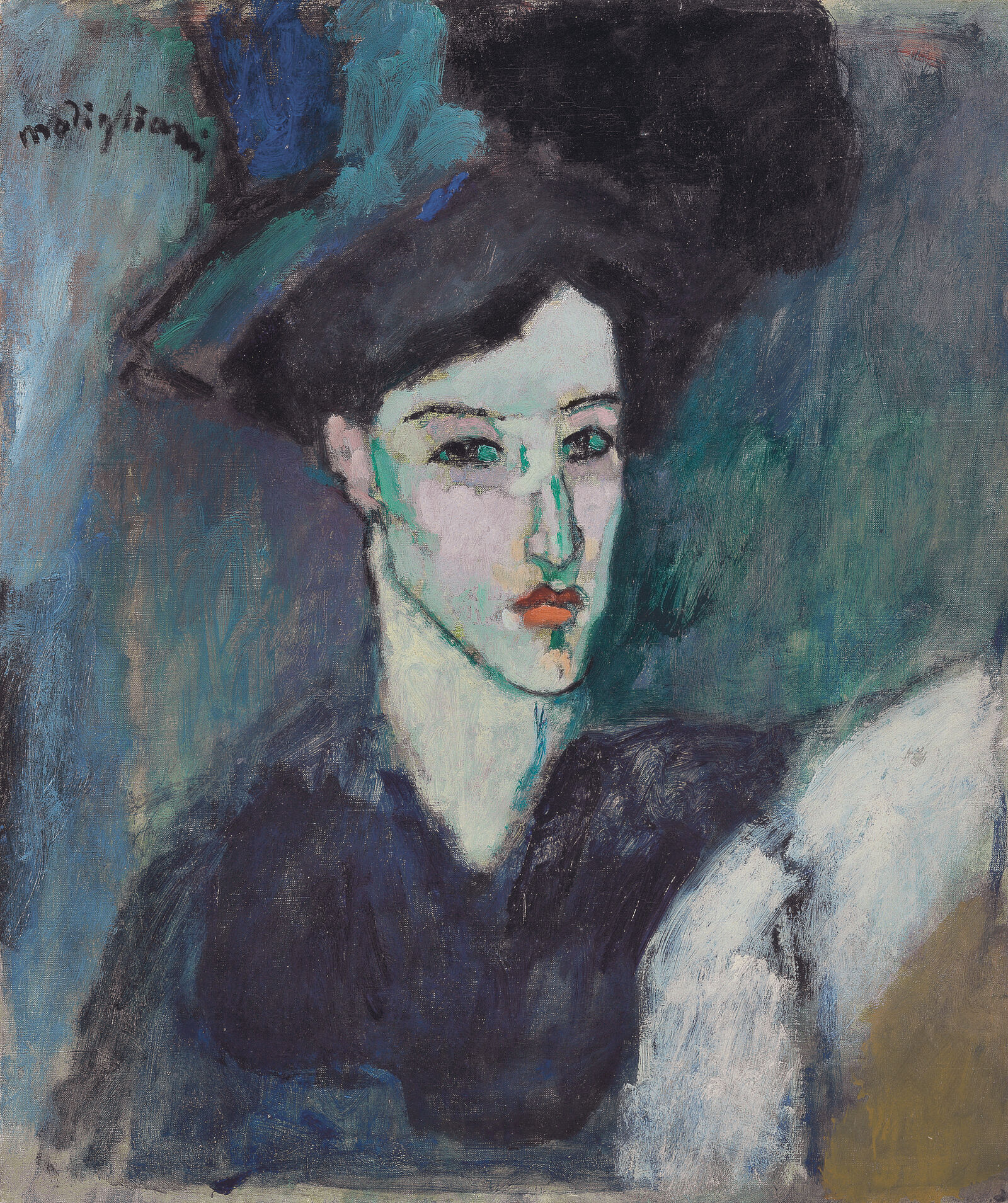

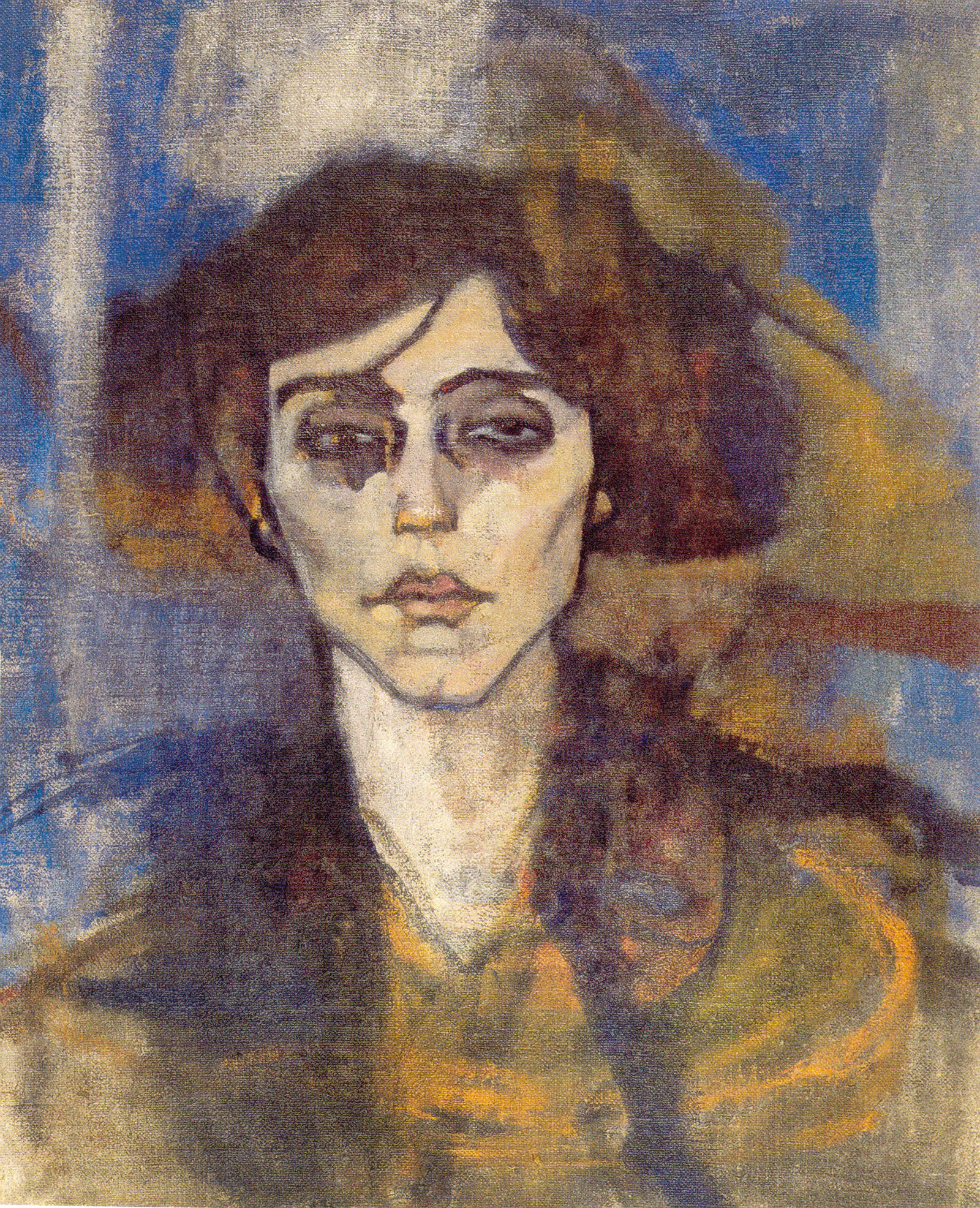

The title the artist chose for this work—The Jewess—is programmatic. Amedeo Modigliani came from a family of liberal Sephardic Jews; although he did not practice the religion, he acknowledged his Jewish origin and associated it with the cosmopolitan atmosphere of his home city of Livorno. The painting, dominated by blue, echoes works from Picasso’s Blue Period.

Amedeo Modigliani: The Jewess, 1907-08, Laure Denier Collection, Laure Denier Collection, Paul Alexandre Family

The environment in which Amedeo Modigliani grows up is a cosmopolitan one: born July 12, 1884, he is the youngest of four children in a liberal Jewish family in the port city of Livorno in Tuscany. His family places a high value on education, and “Dedo,” as everyone calls him, attracts notice early on for his “precocious intelligence and thoughtfulness.”

He devours stacks of books and is intimately acquainted with Dante and Petrarch. Since the family business had gone bankrupt shortly before Amedeo’s birth, his French mother supports them by teaching languages and translating literature, including works by Gabriele D’Annunzio.

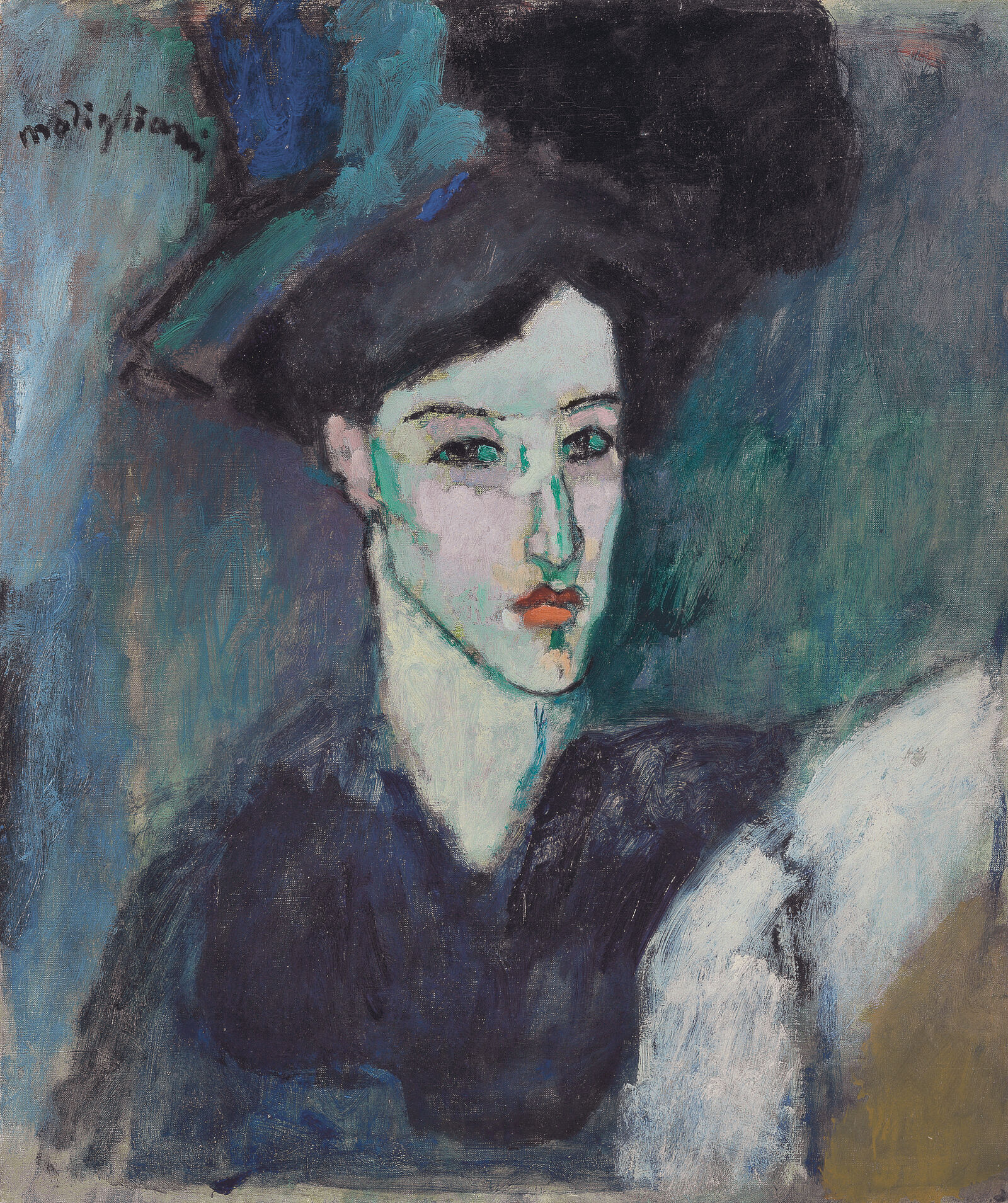

Amedeo Modigliani: The Jewess, 1907-08, Laure Denier Collection, Laure Denier Collection, Paul Alexandre Family

The title the artist chose for this work—The Jewess—is programmatic. Amedeo Modigliani came from a family of liberal Sephardic Jews; although he did not practice the religion, he acknowledged his Jewish origin and associated it with the cosmopolitan atmosphere of his home city of Livorno. The painting, dominated by blue, echoes works from Picasso’s Blue Period.

Dedo, a sickly child, is educated at home. The pen scarcely leaves his hand: he makes little drawings on every sheet of paper, a habit his friends in Montmartre will later observe as well. His philosophically-minded grandfather imparts a humanistic worldview to the boy and frequents the museums with him; Dedo knows the Uffizi in nearby Florence like the back of his hand. And so it comes as no surprise that already as a youth, he firmly resolves to become a painter—especially since his cousins Olga and Corinna Modigliani work as artists in Rome with some success, even showing at the Venice Biennale.

For a time, Amedeo lives in their studio house after a stay in the south of Italy due to a recurring respiratory ailment. The young man’s fragile health, however, does not deter him from studying art in Florence and Venice.

Amedeo Modigliani’s death of tubercular meningitis at the age of thirty-five is only partly the result of his “irregular” lifestyle. Already as a small child, he suffers from pleurisy and contracts typhus at the age of fourteen, followed by serious respiratory illness. For weeks, Amedeo hovers between life and death.

The need to break off his schooling is not unwelcome to the boy, since he is much more interested in drawing and is able to receive well-grounded instruction from Guglielmo Micheli at the age of fourteen. However, in the painter’s studio he contracts tuberculosis, a disease that around 1900 is still incurable and will regularly afflict him for the rest of his life. The fact that Modigliani later abandons sculpture after a promising start in Paris is due not least of all to his weakened physical condition.

Amedeo Modigliani: Head, 1909-1912, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

Photo: bpk / Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe / Wolfgang Pankoke

Through the constant ups and downs, art becomes Modigliani’s driving force and an elixir of life. Even amid the chaos of World War I and in the French Riviera, where he seeks refuge from German troops, he never ceases to paint — until his early death in January 1920. Thereafter, the myth of the ailing artistic genius is not long in coming.

With his conspicuously elegant clothing, the twenty-two-year-old Amedeo Modigliani seems a bit snobbish when he first arrives in Paris. Yet despite the hint of elitism, the Italian makes a good impression and is quickly accepted into artistic circles.

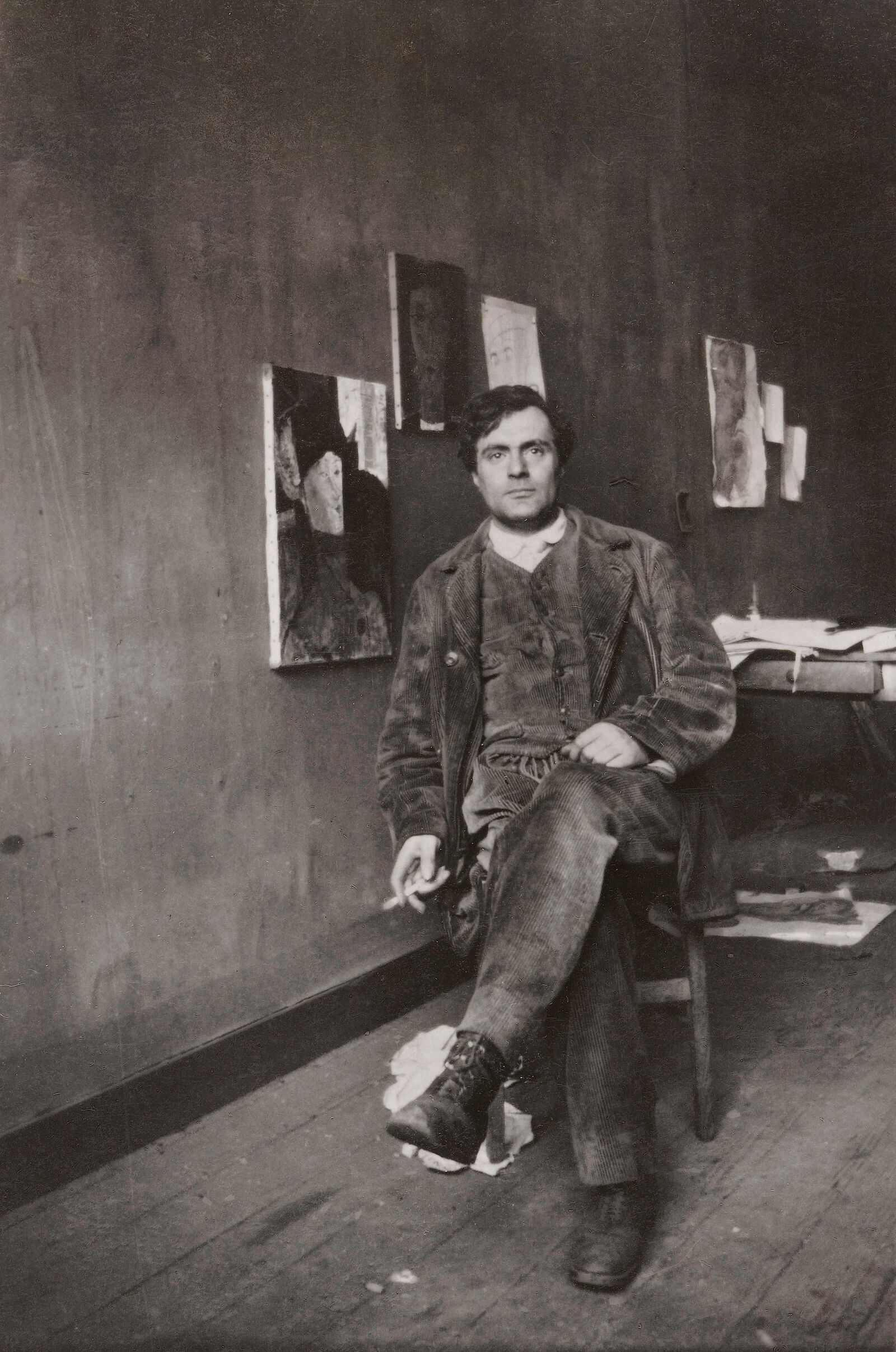

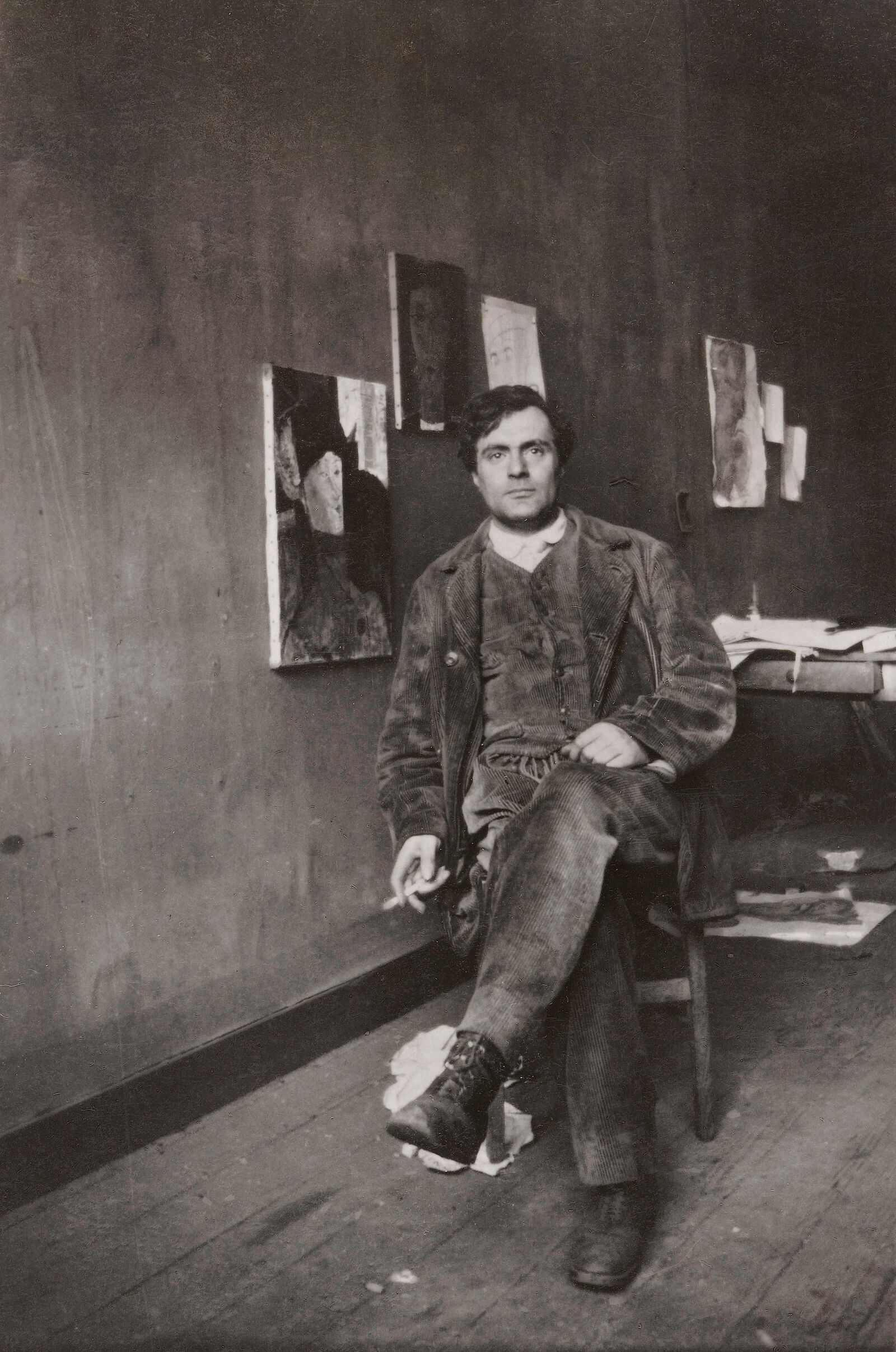

Dominique Couto: Modigliani at his Studio, rue Ravignan, 1915

© bpk, Berlin

In 1906, the twenty-two-year-old Modigliani feels drawn to Paris. An artistic revolution is underway in Montmartre, and Modigliani lives quite close to the legendary Bateau-Lavoir, the dilapidated studio building where Picasso is wrestling with his Demoiselles d’Avignon and the avant-garde is giving birth to Cubism and other visions.

Paul Guillaume: Modigliani in his studio (standing) in the Rue Ravignan at Montmarte, 1915

© akg-images, Berlin

In Paris, Amedeo Modigliani lives a Spartan lifestyle and from the beginning supports himself entirely with his art. Rents in Montmartre are cheap, and his studio on the Rue Ravignan contains only the bare necessities. The art dealer Paul Guillaume photographed the artist there in 1915.

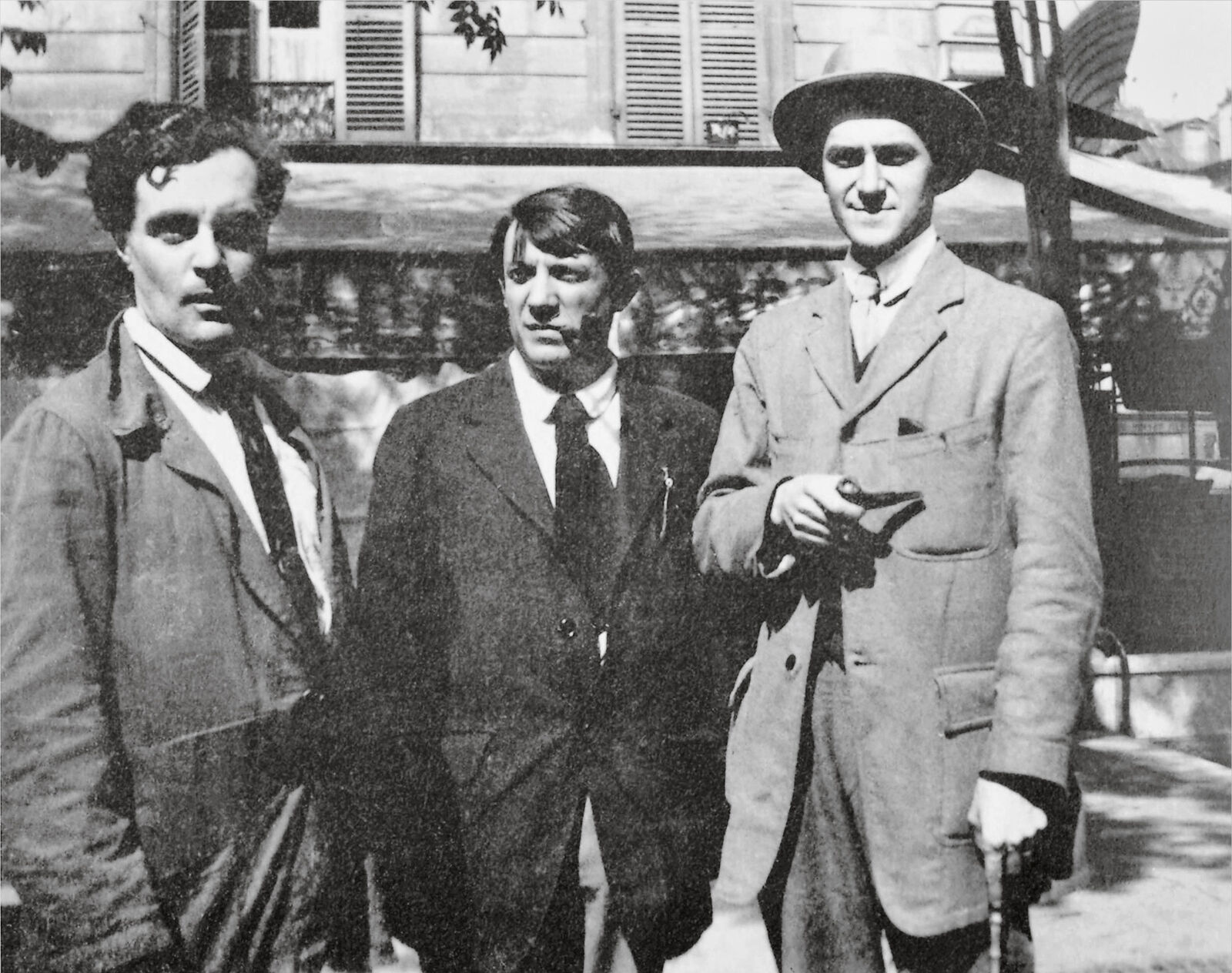

Jean Cocteau: Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso and Andre Salmon in front of the Café de la Rotonde, Paris, August 1916

Amedeo Modigliani lives near Picasso and observes his work on the Demoiselles d’Avignon — and with it the development of Cubism and other variants of modern art.

Unlike the Spaniard Picasso, who is teased for his accent, the suave Modigliani speaks fluent French and is fond of quoting Baudelaire — and especially Dante. Women flock to this refined, bright-eyed charmer, and his fellow artists are taken by his friendly, open demeanor and witty conversation. Although he strikes an unusual figure with his large felt hat, velvet suit, and red scarf, his skillful hands and confident line bear witness to his professional skill.

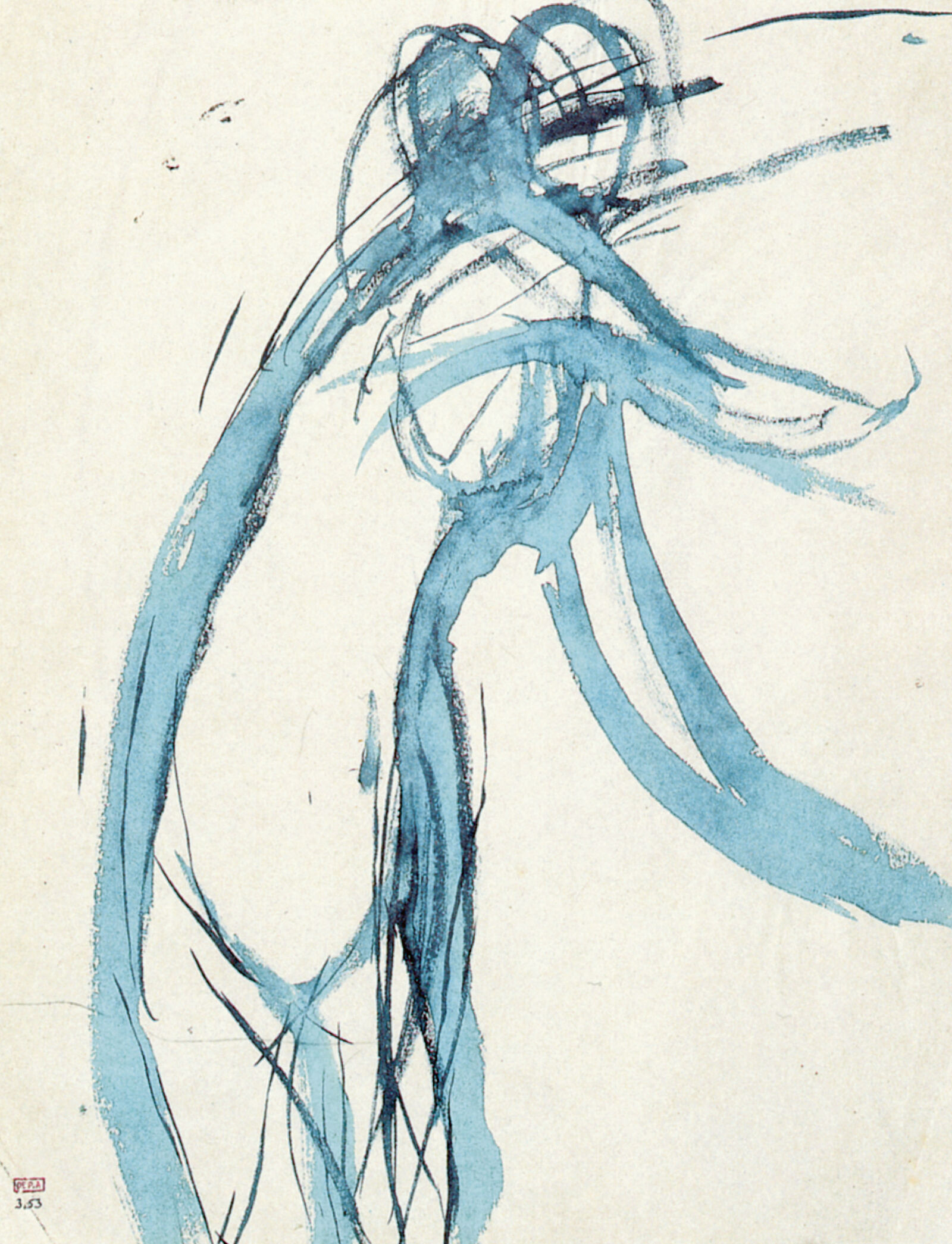

Amedeo Modigliani: Female Figure in Movement, 1909, Privatsammlung, Private collection, formerly Paul Alexandre Collection

The sketch in blue ink shows a slender female body. In its direct evocation of movement, it recalls the watercolors of the sculptor Auguste Rodin.

Modigliani makes the rounds, drawing his patron, the physician Paul Alexandre, and of course the companions he flirts with in the cafés and dance theaters. Night soon turns to day, and the bohemian life works its magic on the young man from sheltered circumstances — along with the extraordinary, self-confident women.

Among them is his friend Maud Abrantès, who like Modigliani is drawn to literature and art. Clearly addicted to morphine, she is featured in an impressive portrait by Modigliani.

Amedeo Modigliani: Nude With a Hat (recto) / Portrait of Maud Abrantès (verso), 1908, Hecht Museum Collection

Modigliani often used canvases multiple times. One side of this piece shows the American Leontine Phipps, who adopted the artist name Maud Abrantès. Modigliani portrays his morphine-addicted friend in 1908.

Amedeo Modigliani: Nude With a Hat (recto) / Portrait of Maud Abrantès (verso), 1908, Hecht Museum Collection

On the front, the pale figure of a Nude with a Hat captures the artistic milieu of Montmartre.

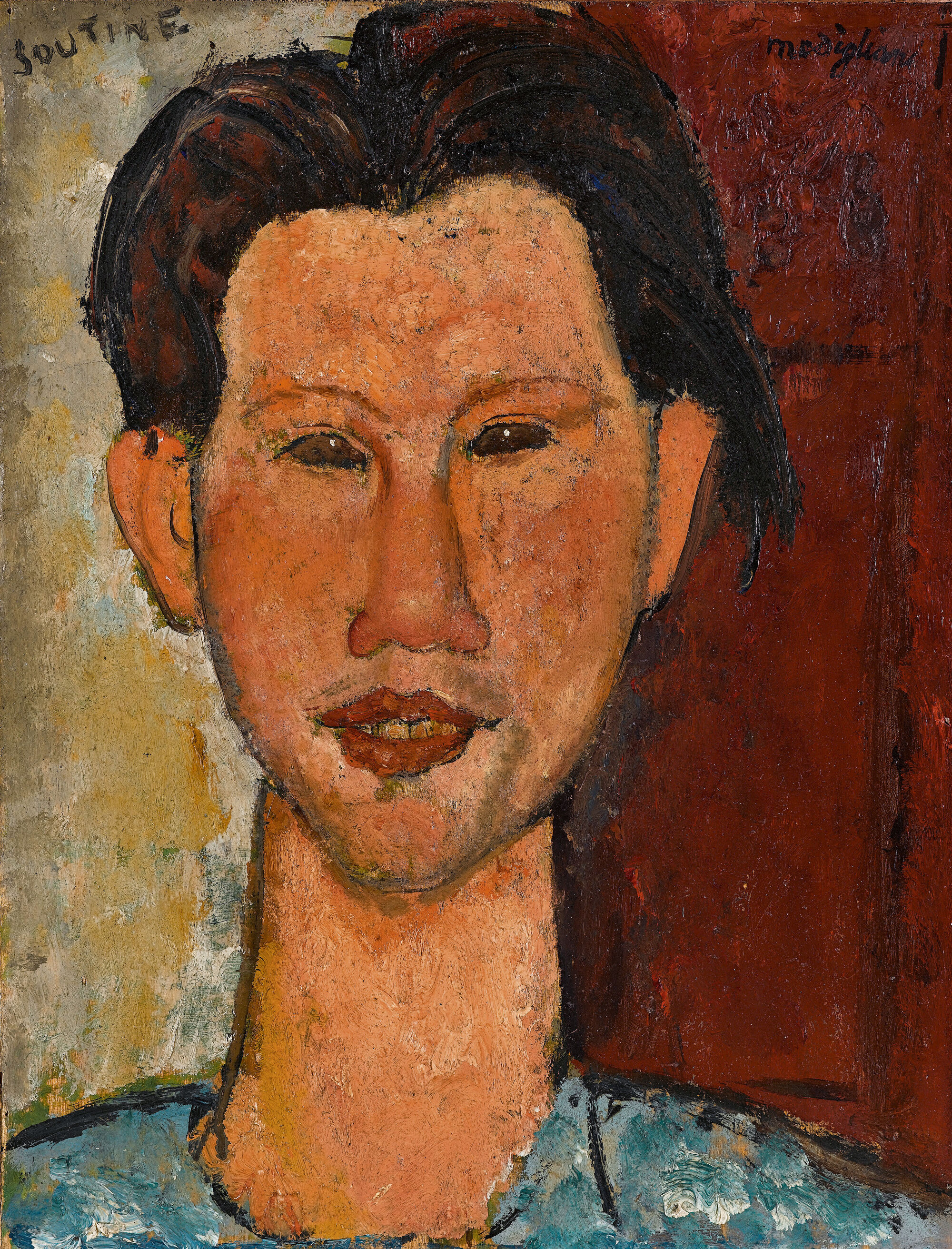

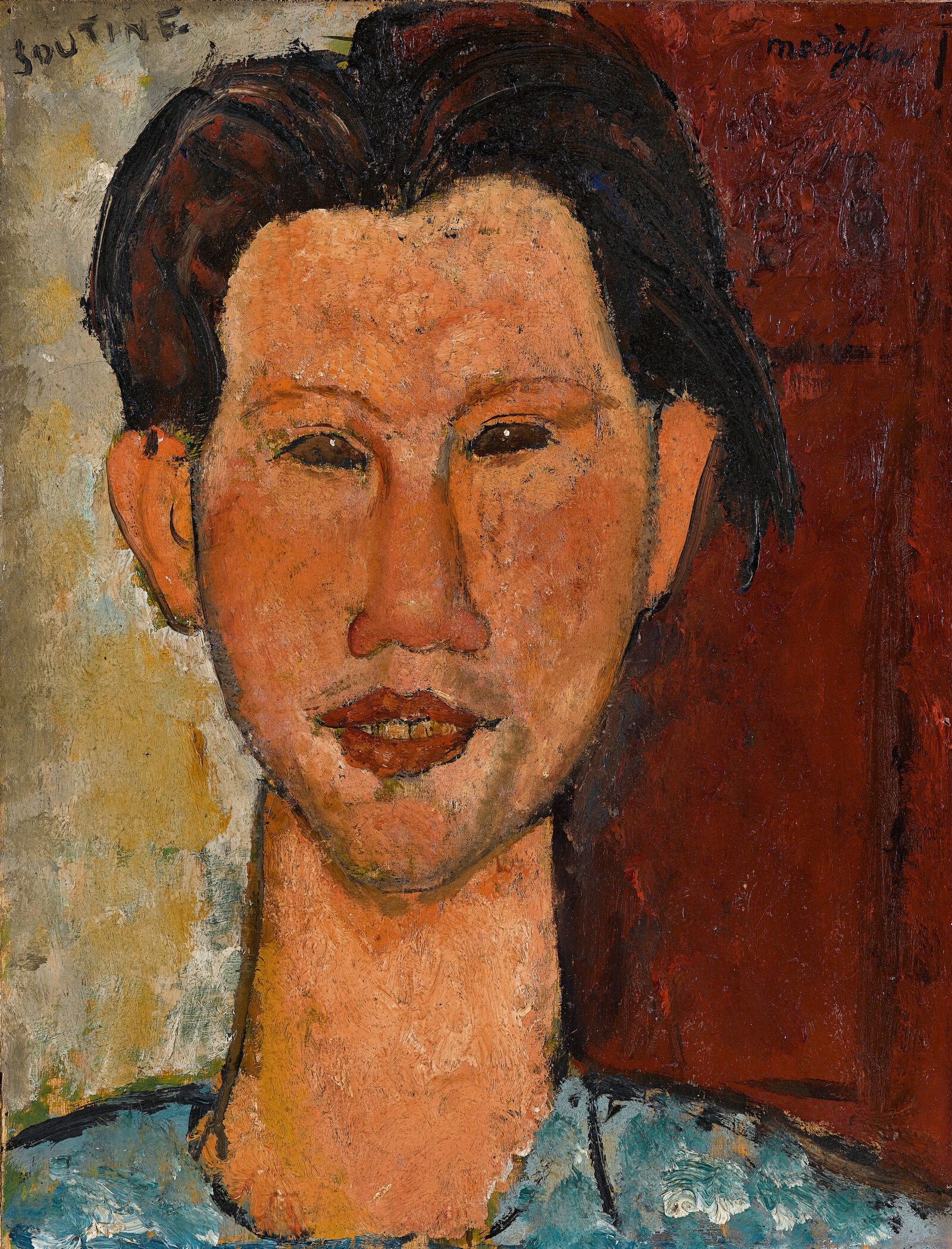

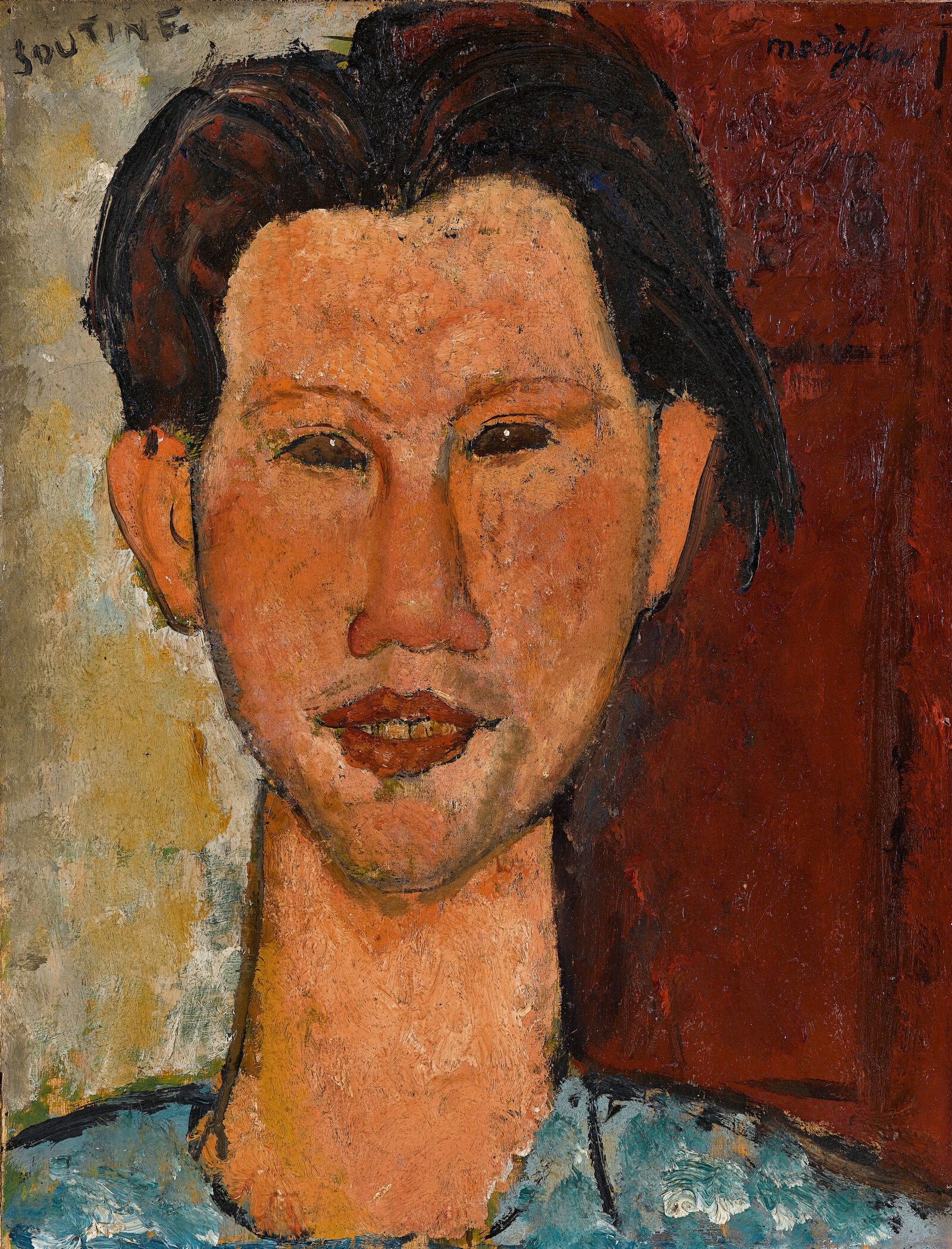

Few painters have portrayed their artistic milieu as extensively as Modigliani. He paints three portraits of Chaïm Soutine, an artist ten years his junior who had come from then-Russian Belarus. The two painters are drawn to each other from the moment they meet, perhaps also due to their shared Jewish roots. In the small portrait from 1915, Soutine looks alert and youthfully impudent.

Amedeo Modigliani: Chaïm Soutine, 1915, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

As sabers rattle throughout Europe, the atmosphere in Montmartre in the summer of 1914 is still pervaded by a fascinating openness. Even after the outbreak of World War I, artists are interested less in national loyalties than in the thrill of experimentation. The revolution in modern art is propelled not least of all by immigrants who have arrived in Paris seeking the free exchange of ideas and who nonchalantly introduce their traditions into the avant-garde. Modigliani observes his environment carefully and paints his milieu, including new colleagues like the Mexican artist Diego Rivera who have come to the city on the Seine for inspiration.

Amedeo Modigliani: Diego Rivera, 1914, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, acquired in 1986 through the Freunde der Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen with the support from the business community of North Rhine-Westphalia and state funds

© bpk / Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf / Walter Klein

Between 1911 and 1921, the Mexican painter Diego Rivera made multiple trips to Paris and explored Cubism there. Modigliani was friends with Rivera and painted the Mexican’s portrait several times. This image from 1914 is one of the first paintings Modigliani produced after his intensive phase of sculptural work.

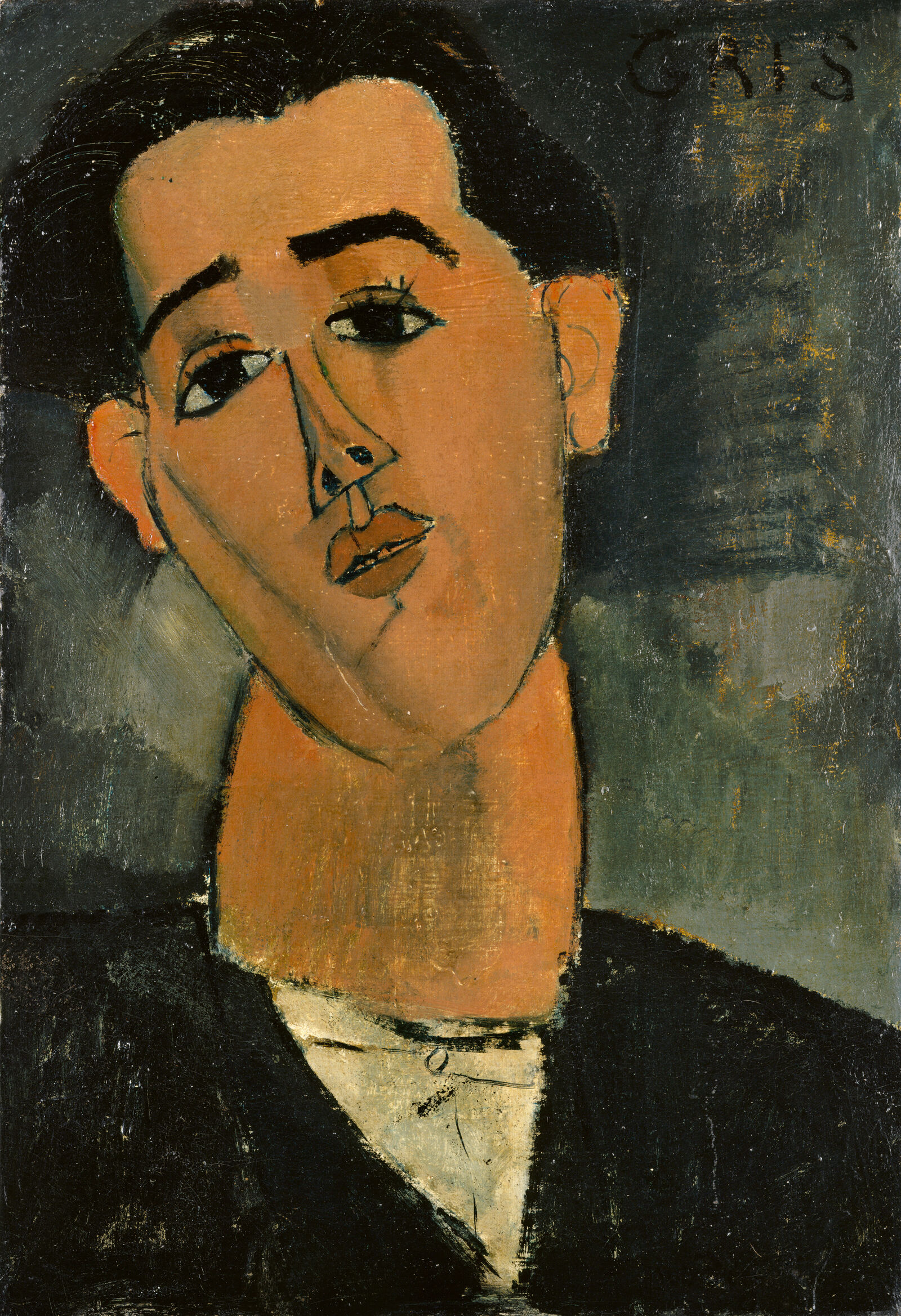

Amedeo Modigliani: Juan Gris, 1915, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), 1967

Photo: bpk / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Like Modigliani, the Spaniard Juan Gris came to Paris in 1906. Along with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, he developed Synthetic Cubism, a style from which Modigliani was to glean only formal inspiration. In this portrait from 1915, the tilted head, long eyelashes, and delicate facial features make Gris seem surprisingly feminine, like a pendant to Modigliani’s images of modern women with short hair.

Modigliani’s style is now distinct and unmistakable, especially in its reduction to essences. The portraits of his friends now confront the viewer directly, as if using their own countenances to underscore their artistic convictions. This holds true for Juan Gris and Moïse Kisling as well as Chaïm Soutine, with whom Modigliani has a special connection. Around 1915, the faces become even flatter, almost like disks. Eyes and nose are indicated by simple contours, and the viewer is involuntarily reminded of the almost 5,000-year-old Cycladic idols that also made an impression on Brâncuşi and Picasso.

Amedeo Modigliani: Moïse Kisling, 1916, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Jesi Collection

Photo: bpk / Scala - courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali

With its slightly shifted perspectives, the portrait of Moïse Kisling shows faint echoes of Cubism. Kisling, who grew up in a Polish Jewish family in Krakow, arrives in Paris in 1910 and soon belongs to Modigliani’s inner circle. Like his later wife, the painter Renée Gros, he wears bobbed hair with bangs. With their suits and neckties, the pair embody the modern artist couple.

The intellectual women who surrounded Amedeo Modigliani in his childhood not only shape his sensibilities, but also influence his interaction with female friends and lovers. Musical, literary women are especially attractive to him — like the urbane, drug-addicted Maud Abrantès (morphine was downright fashionable among the affluent bourgeoisie) or the Russian poetess Anna Akhmatova. For Modigliani, Akhmatova is a kindred spirit: in the summer of 1910, they visit museums in Paris, and he creates drawings of his brilliant, beautiful acquaintance.

The painter’s two-year affair with the highly emancipated writer and journalist Beatrice Hastings is turbulent and exhausting. Modigliani makes multiple portraits of his British companion; a painting from 1915 bears the telling title “Madam Pompadour” — with the English spelling “Madam” — in allusion to the mistress of Louis XV. The couple have no loyalties to each other, and infidelity is the order of the day. In 1916, the liaison ends when Modigliani decides to move in with Jeanne Hébuterne, an art student almost fourteen years his junior.

Amedeo Modigliani: Portrait of a Girl (Victoria), 1916, Tate, Tate, bequeathed by C. Frank Stoop 1933

Modigliani painted this image of a young woman called Victoria over a portrait of Beatrice Hastings.

The relationship with Hébuterne is much more harmonious: Modigliani produces over twenty portraits of his final companion, images that tell of an affectionate gaze. His distinctive style, however, with its elongated necks, tilted heads, and almond-shaped eyes, emerges during the stormy liaison with Hastings.

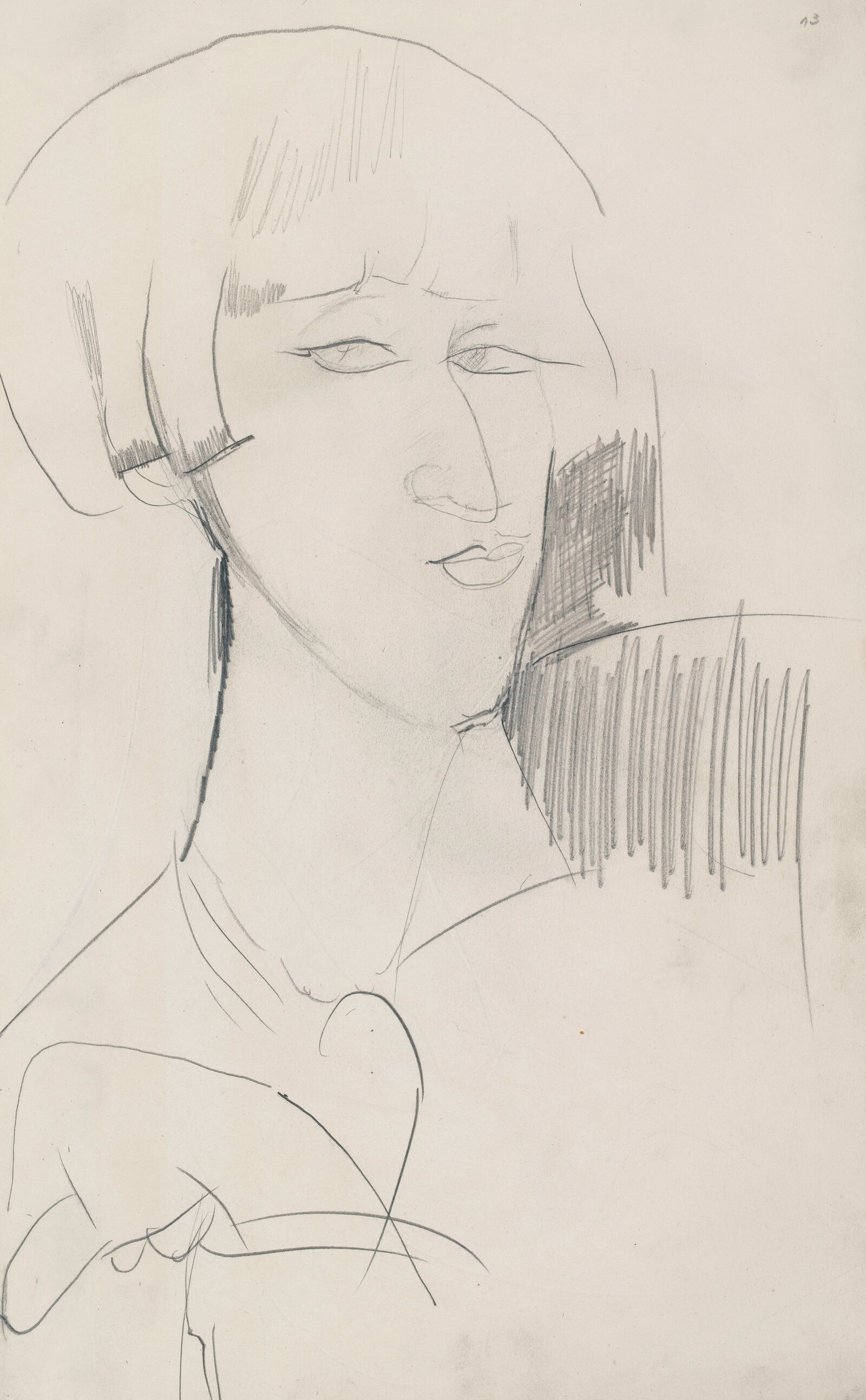

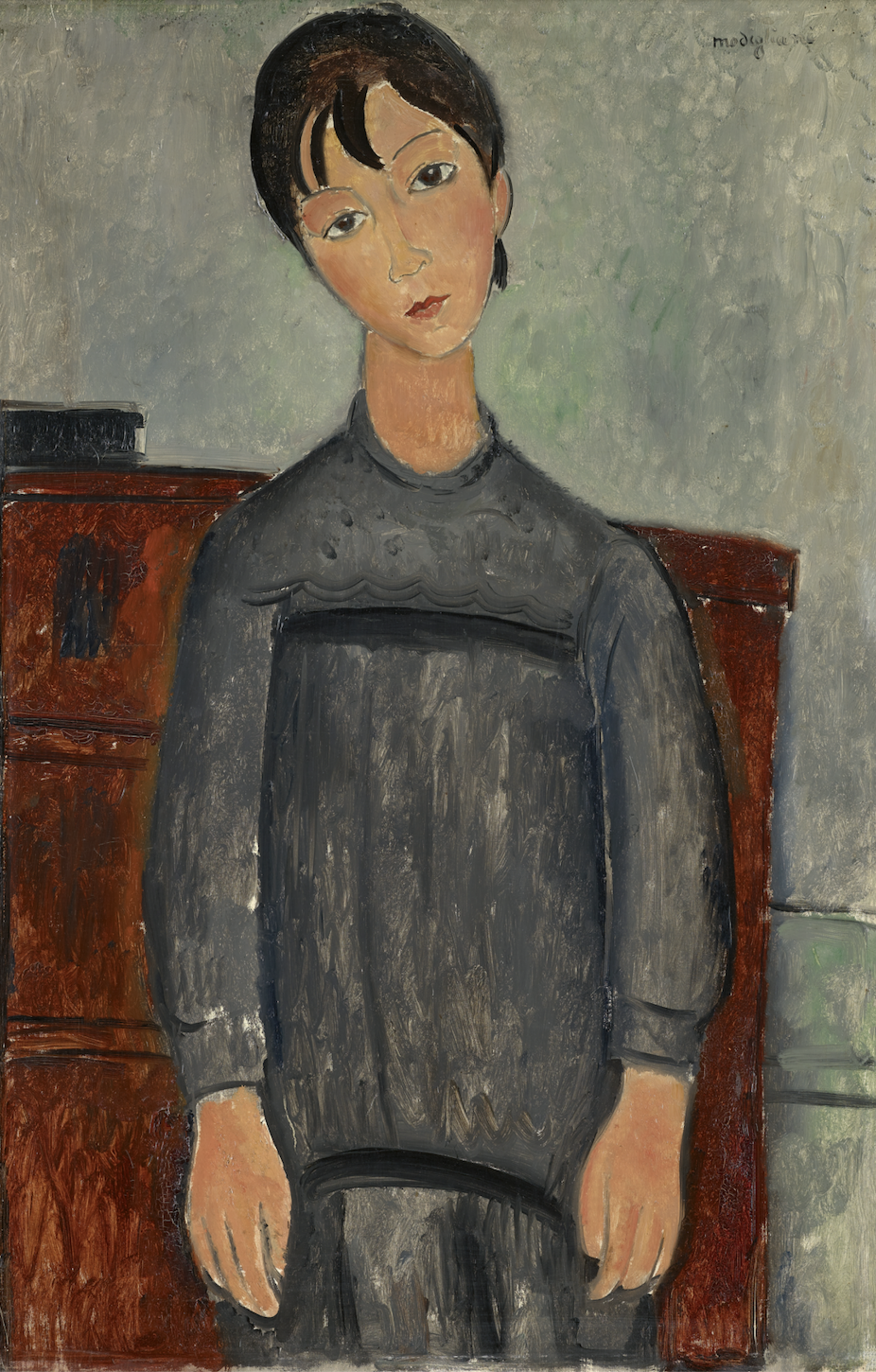

The unknown subject seems girlish and lost in thought—a characteristic feature of Modigliani’s late portraits of women. With her pageboy haircut and necktie, she is a typical example of the femme moderne. The portrait may show the artist Renée Kisling, who was known for this style of hair and clothing.

Amedeo Modigliani: Young Girl with a Striped Blouse, 1917, Nahmad Collection

Photo: Christie's Images / Bridgeman Images

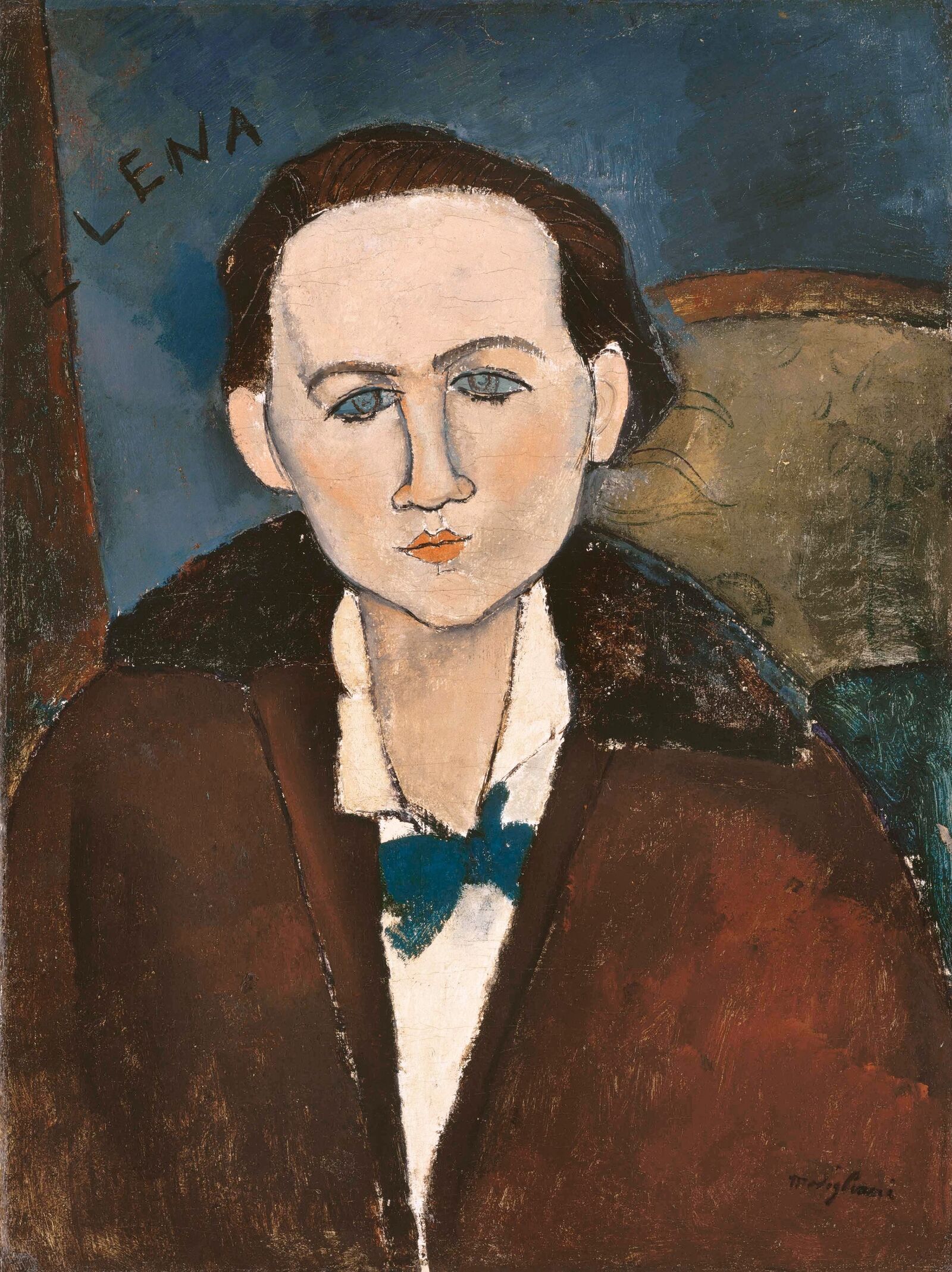

Trousers, neckties, and short hair: around the turn of the century, masculine dress for women is considered shocking and scandalous — no one cares that it might also be practical. Thus it is all the more remarkable that as early as World War I, Amedeo Modigliani paints a whole series of femmes modernes with pageboy hairstyles, bobs, and even the ultrashort boy cut worn by the bookseller Elena Povolozky. Modigliani anticipates what will become chic only in the late 1920s, but also has connections to queer circles and the fashion scene.

Amedeo Modigliani: Elena Povolozky, 1917, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Photo: akg-images / Album

Hélène Joséphine Bernie Povolozky moved to Paris from Rennes to become an artist. With her excellent network, she then began exhibiting avant-garde art together with her husband, who had emigrated from Russia. She provided financial support for Modigliani, who expressed his appreciation in 1917 with one of his finest portraits. It shows the gallerist and bookseller with a critical, melancholy expression, wearing men’s clothing and short, bobbed hair. Povolozky would still cut a fine figure today, and the painting involuntarily echoes Picasso’s portrait of his patron Gertrude Stein.

Androgynous clothing is popular among progressive artist couples. With their plain suits and bobbed hair or coupe garçonne, Moïse and Renée Kisling look like twins. Modigliani is good friends with both of them.

Amedeo Modigliani: Renée Kisling, 1915, Centre Pompidou, Paris, National Museum of Modern Art / Center of Industrial Creation; purchased 1963

He also associates with Ossip Zadkine and the latter’s partner Nina Hamnett, who makes no secret of her bisexual affairs. The scintillating “Queen of Bohemia,” as Picasso calls her, even borrows a pair of trousers from Modigliani and takes the Paris nightclub scene by storm, costumed as an “Apache” — with a female dance partner. In Paris, costume balls and studio parties also offer welcome opportunities to exchange roles.

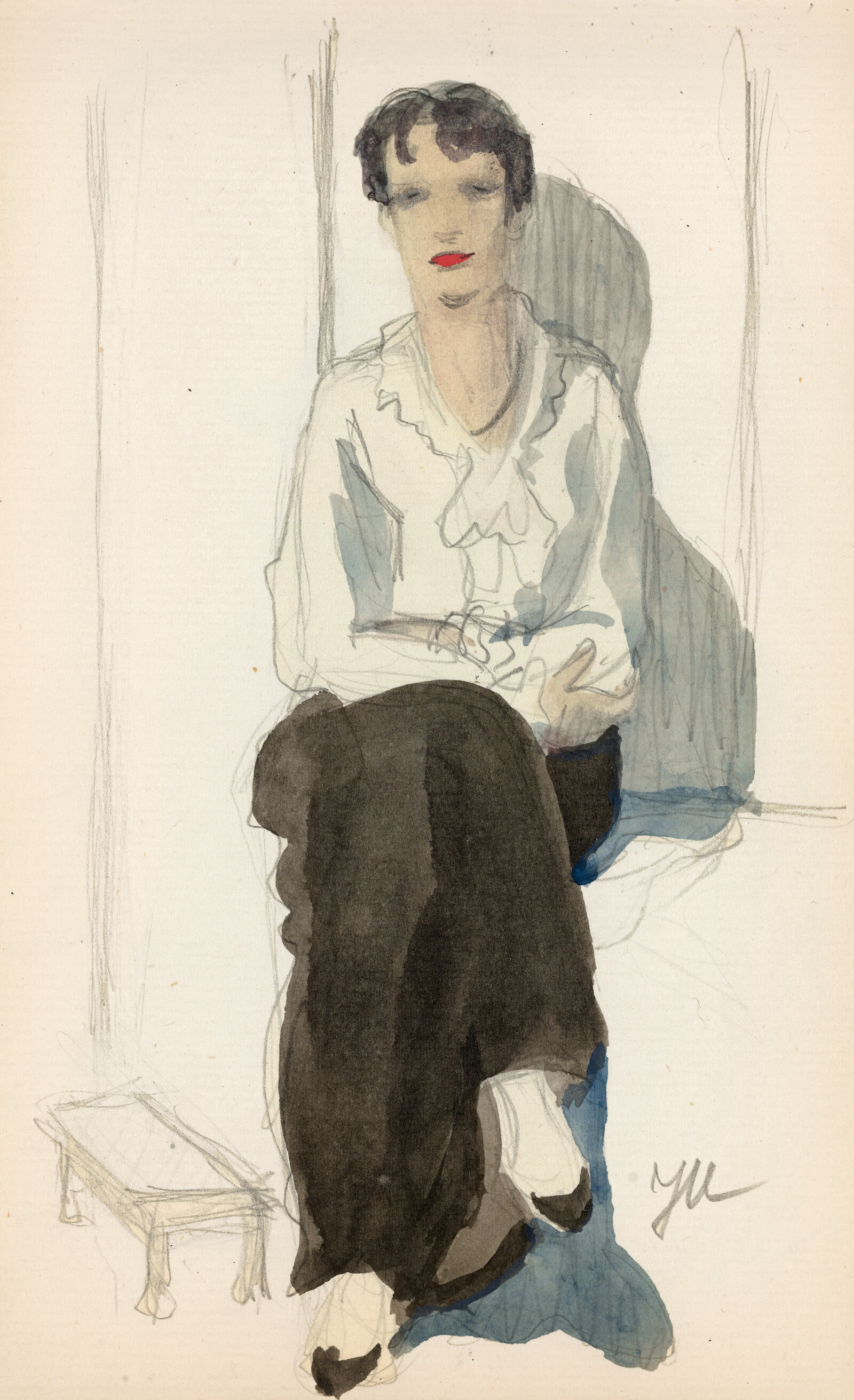

Jeanne Mammen: Sketchbook II, Page 38, 1910–14, Jeanne-Mammen-Stiftung im Stadtmuseum Berlin

Photo: VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024 / Jeanne-Mammen-Stiftung im Stadtmuseum Berlin / Dorin Alexandru Ionita, Berlin

Along with Amedeo Modigliani, only a few female artists explored a new image of womanhood, such as would later characterize the New Objectivity of the late 1920s. Among them were Jeanne Mammen and Émilie Charmy. Around 1914, Mammen drew self-confident women in men’s clothing or at least with bobbed hair, as this example from her sketchbook demonstrates.

Emilie Charmy: Self-Portrait, 1906/07, Galerie Bernard Bouche, Paris

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

In her self-portrait, the artist Émilie Charmy shows herself in a sailor shirt, an item of clothing which, despite its masculine connotations, was also worn by children around the turn of the century. Here, Charmy distances herself from the traditional female image in two ways: as a childlike woman, she dissociates herself from the role of mother, while the masculine accoutrements convey her emancipated position.

Only ostensibly chaste, the young woman with empty gray eyes wraps herself in a white cloth — while still revealing a view of her breasts. Modigliani places the half-nude figure, painted toward the end of his exile in the French Riviera, in a simple, undefined interior. The color of her eyes extends to the entire surface of the wall, albeit with nuances of green and a delicate play of shadows. During this period, Modigliani visits the elderly Pierre-Auguste Renoir and pays homage to his great role model. At the same time, he also sets different accents, cropping his subjects with a boldness that would never have been embraced by Renoir.

Amedeo Modigliani: Young Woman in a Chemise, 1918, Albertina, Wien, Sammlung Batliner

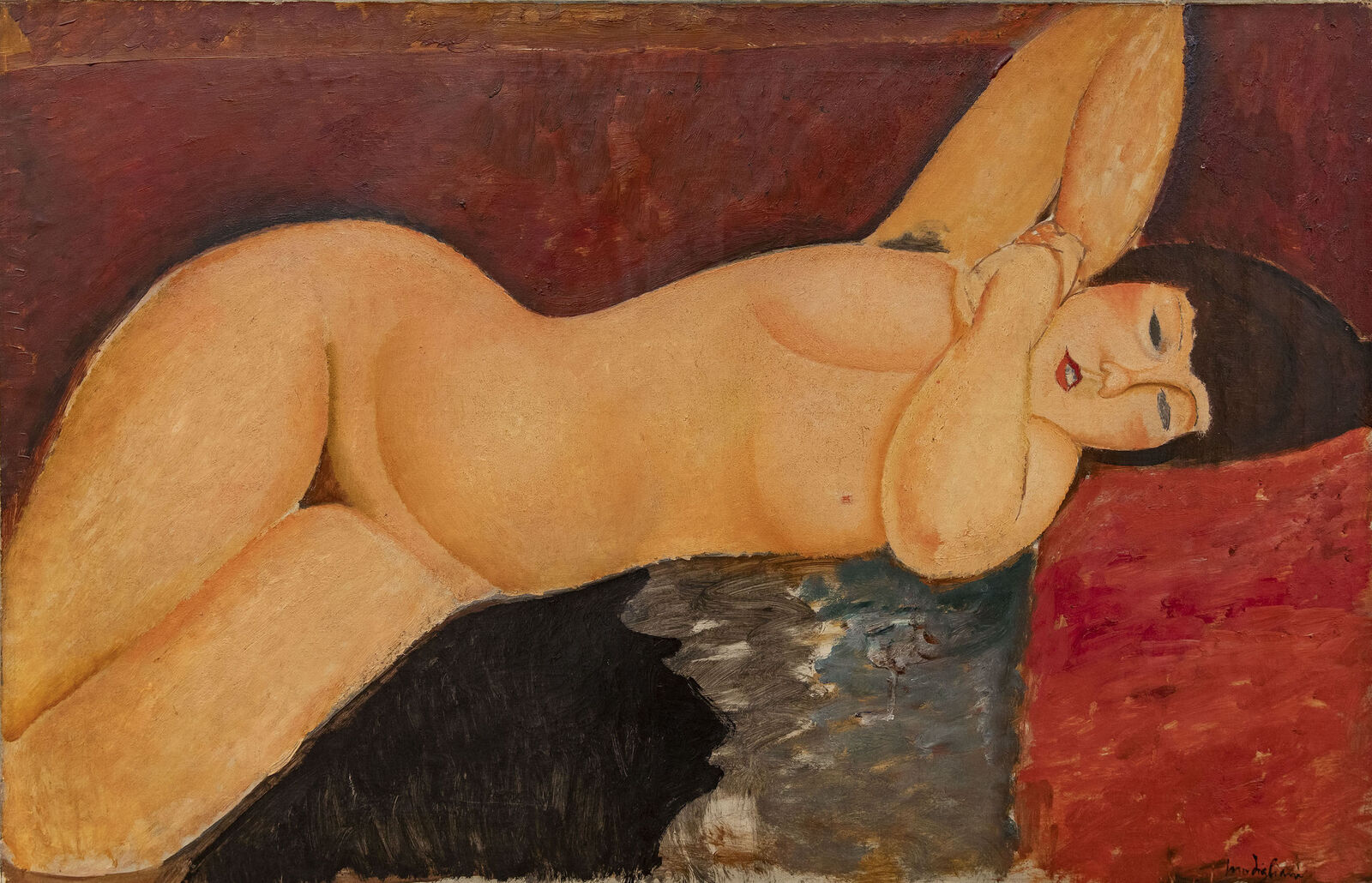

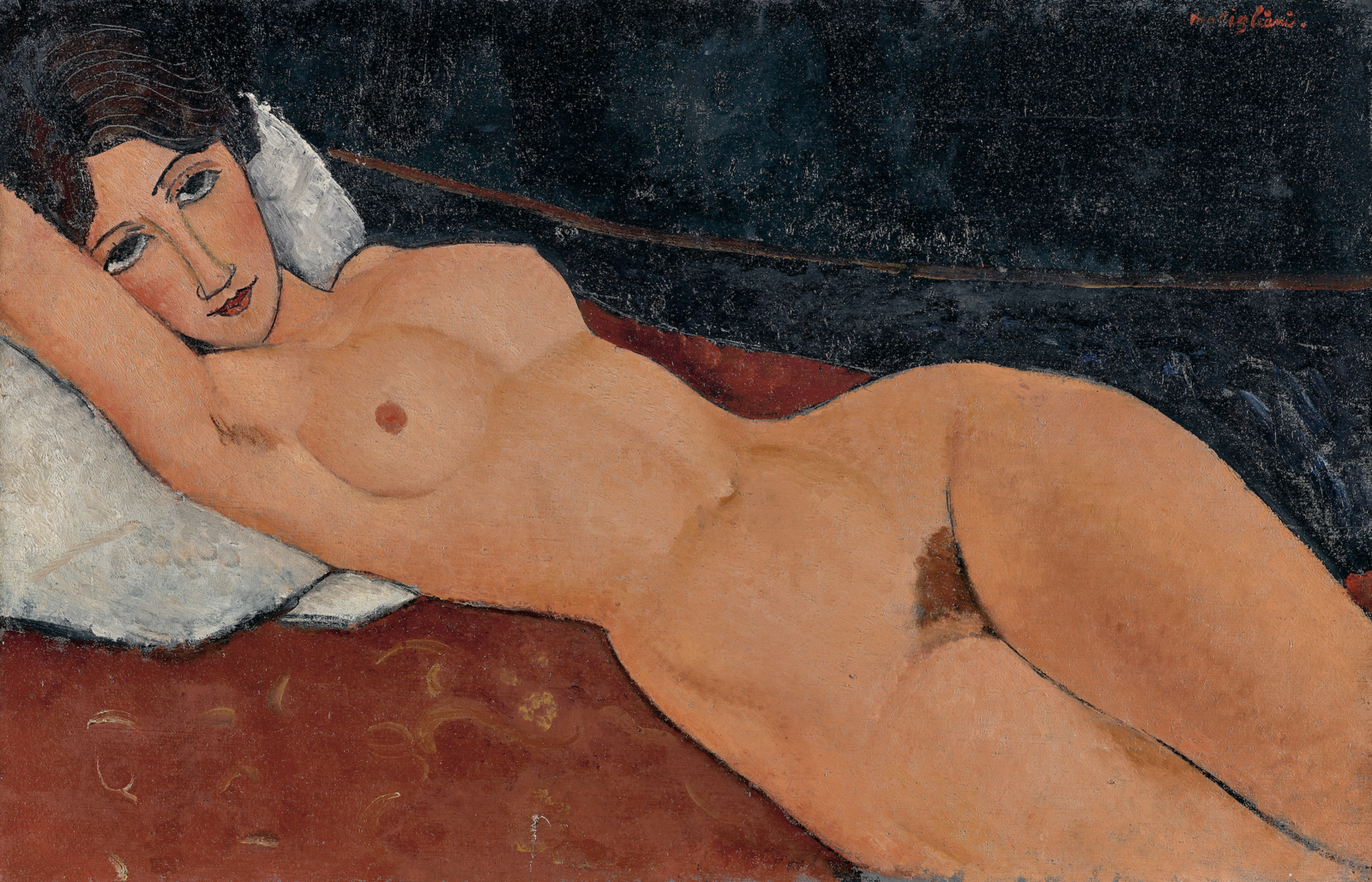

Along with portraits, Modigliani once again focuses intensively on nudes. Picasso’s Demoiselles d'Avignon, painted in 1907, is shown in public for the first time in 1916 and demands a response from the Italian artist. While Modigliani has no interest in deconstructing the figure, his nudes — who loll about casually, echoing traditional imagery — still manage to burst the bounds of the frame.

Amedeo Modigliani: Reclining Nude with Intertwined Hands, 1917, Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin

Modigliani’s Lying Nude with Joined Hands seems dreamy and downright playful. Stretching and lolling, the young woman fills the space around her. She evokes associations with the Sleeping Ariadne, a Roman copy after a Greek original that the artist saw in the Vatican Museums in 1900–1901.

Modigliani prefers tightly cropped compositions, intensifying the flesh tones to an almost Pompeiian red and taking liberties with the proportions. He may be the only modern artist to invoke Renaissance painting without overstatement, imbuing his nudes with a timeless, classical quality.

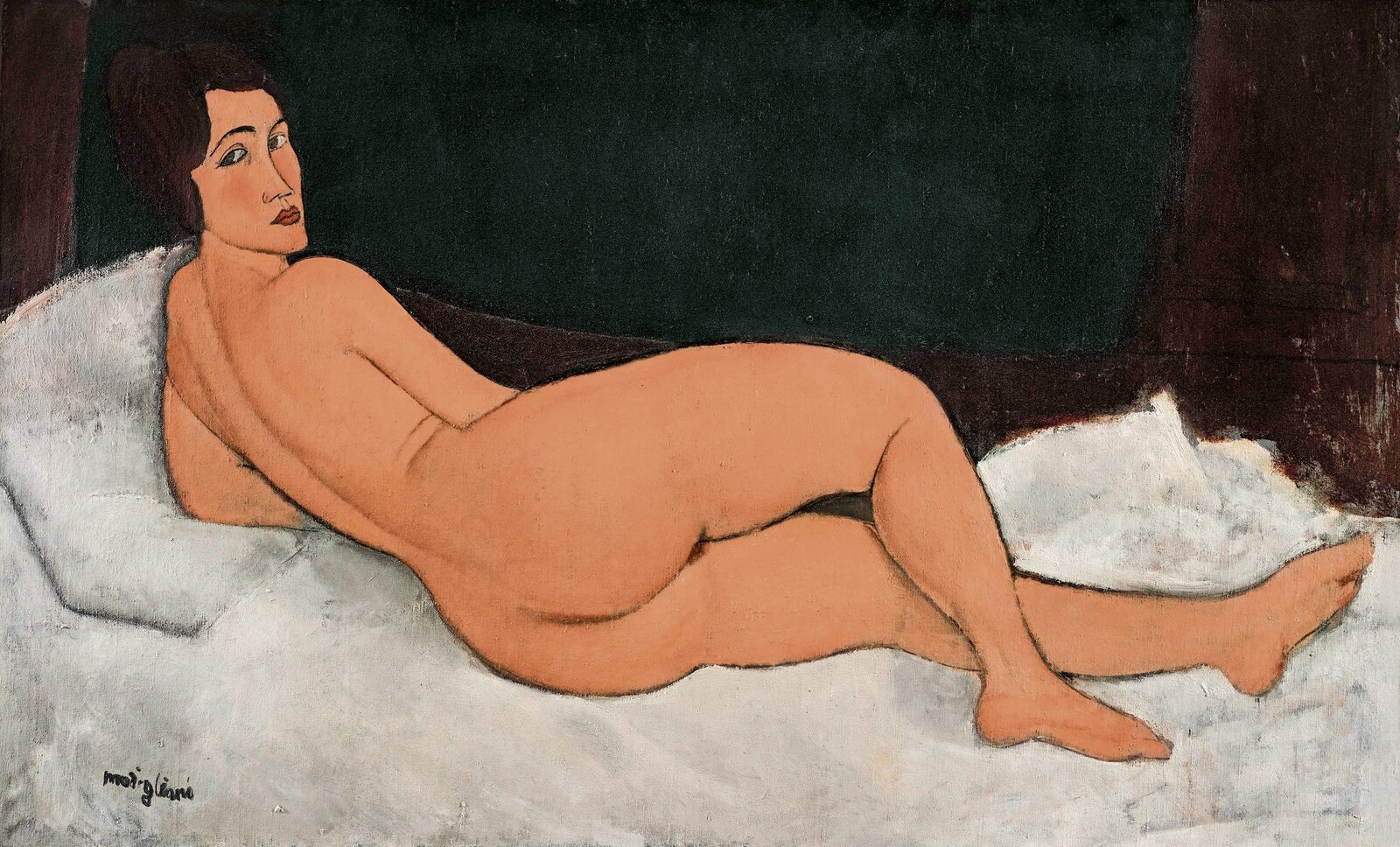

Amedeo Modigliani: Reclining Nude (on the Left Side), 1917, Nahmad Collection

“First look me in the eye,” this gaze seems to say. Amedeo Modigliani did not have to break with tradition to forge new artistic paths: the female nude reclining on her side clearly recalls Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Grande Odalisque from the Louvre in Paris. But in Modigliani’s work, it is the anonymous nude model who sets the terms of the encounter.

These are not destitute, addicted prostitutes, as some have insisted. And the scandal provoked by the artist’s only solo exhibition in 1917 is in fact no scandal at all. A nude by Modigliani displayed in the window of Berthe Weill’s gallery on the Rue Taitbout in Paris causes consternation among policemen at the nearby station; only by removing the “offensive nude” from her window can Weill keep the exhibition from being shut down. It is the pubic hair that the police chief finds objectionable — or is it perhaps also the model’s direct gaze, with the self-confidence that it expresses?

Amedeo Modigliani: Reclining Nude on a White Cushion, 1917, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, erworben mit Lotto-Mitteln 1959

Bedroom eyes: Modigliani places his seductive Reclining Nude on a White Cushion against a warm, velvety red. He evokes associations with mythologically veiled images of nude goddesses and doubtless has Titian’s Venus of Urbino in mind as well, which he knew from the Uffizi in Florence — with the obvious difference that this modern “rebirth” is a very earthly one, complete with pubic hair. This painted nude may have been the one that so alarmed the police in 1917.

Paula Modersohn-Becker: Reclining Female Nude, 1905/06, Döpfner Collection

The same direct eroticism seen in Modigliani’s work also characterizes the nudes of Paula Modersohn-Becker and Émilie Charmy. They, too, show pubic hair and create tightly cropped compositions in which the figures fill almost the entire space of the picture, heightening the tension. Modersohn-Becker painted her Reclining Female Nude as early as 1905–6, shortly before Modigliani arrived in Paris.

Modigliani’s art finds its counterparts less in Paris than among his fellow artists in German-speaking countries. Both August Macke and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner prized directness and naturalness, and, like Modigliani, also distanced themselves from the image of woman as femme fatale.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner: Nude against Blue Background, 1911, Buchheim Museum der Phantasie, Bernried am Starnberger See

Photo: akg-images

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Nude Against a Blue Background from 1911 shows parallels to Modigliani’s seated nudes ...

August Macke: Nude with Coral Necklace, 1910, Sprengel Museum Hannover, Donation Sprengel Collection 1969

Photo: bpk / Sprengel Museum Hannover, Schenkung Sammlung Sprengel 1969 / Herling/Gwose/Werner

... as does the self-absorbed Nude with Coral Necklace by August Macke from 1910.

His pictures have endless dignity and elegance. You will find nothing common, coarse, or banal in them.

Amedeo Modigliani: Young Woman in a Yellow Dress (Renée Modot), 1918, Fondazione Francesco Federico Cerruti per l’Arte Collection. Long-term loan, Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin

War looms: in March 1918, Modigliani and Jeanne Hébuterne retreat to Cagnes-sur-Mer and Nice in the South of France, seeking refuge from the bombs. The artist’s respiratory condition has been deteriorating for months, and the mild Mediterranean climate promises relief. The couple will remain in the French Riviera for over a year. Their daughter Jeanne is born shortly after the armistice in November 1918, but Modigliani lacks the necessary documents for a proper wedding.

During this phase he even begins painting landscapes reminiscent of the work of Paul Cézanne — and not solely due to the delicate colors. Above all, however, this period is marked by the emergence of the artist’s late, “classicistic” style. His contours become even more elongated and softer, the loosely applied pastel tones more cheerful. Harmony and beauty play an ever-greater role, and the faces of his subjects, with their often pupilless eyes, seem enraptured.

Amedeo Modigliani: Girl in a Black Pinafore, 1918, Kunstmuseum Basel, Gift of Georgette Denise Simon, Basel

In the South of France in 1917–18, Modigliani frequently works on multiple paintings at once. Despite her expression of knowing melancholy, the Girl in a Black Pinafore seems childlike, partly because of the awkwardness of her hands. The long neck and tilted head are typical of the painter, yet are also reminiscent of the child portraits of Paula Modersohn-Becker.

In the French Riviera, Modigliani paints portraits of serving maids, shop girls, and, for the first time, children. His favorite model is Jeanne, the love of his life, but their time together is quickly running out.

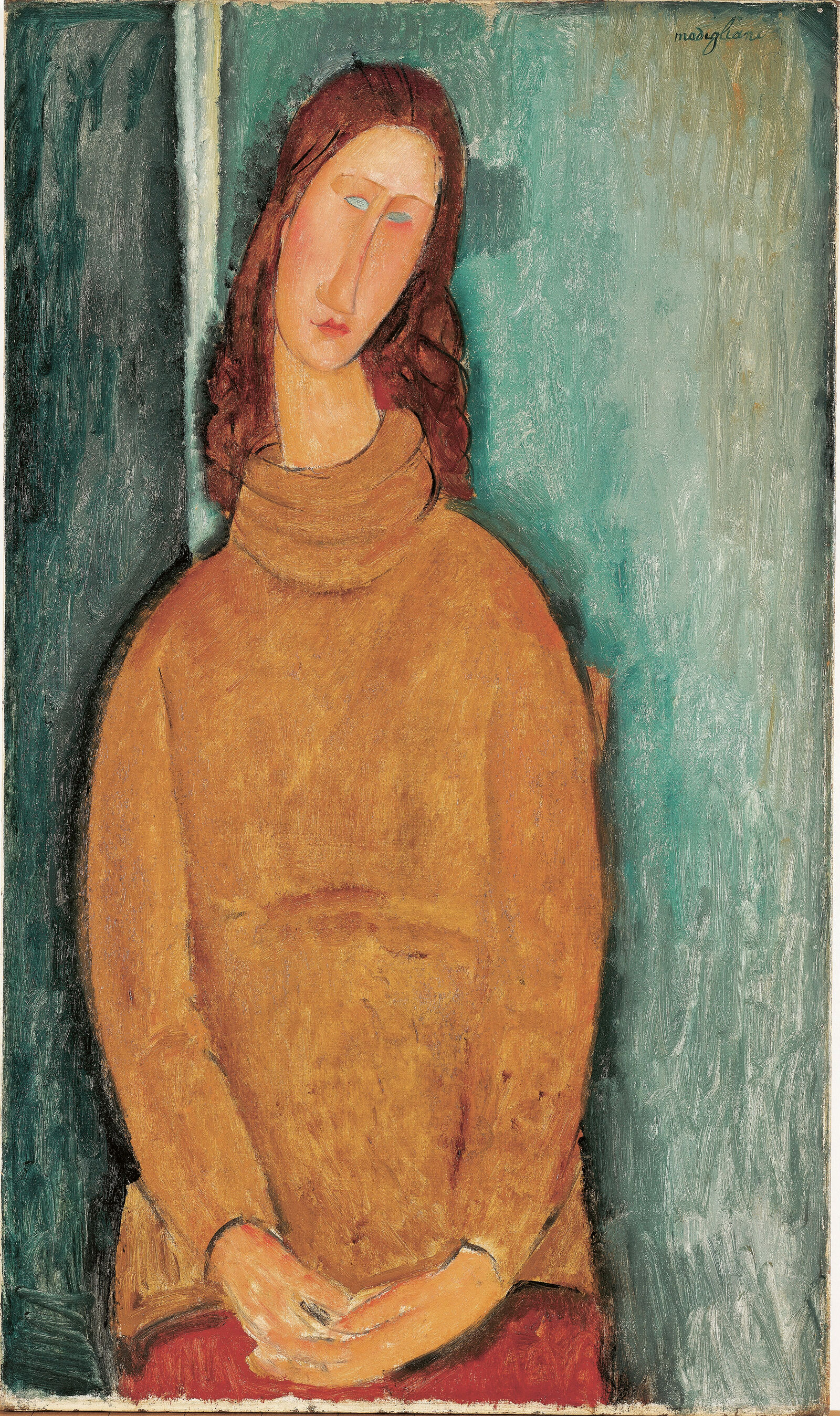

Amedeo Modigliani: Jeanne Hébuterne in a Yellow Sweater, 1919, Ohara Museum of Art, Kurashiki

Jeanne’s copper-red hair frames her tilted face like the veil of a Madonna, while her bright blue eyes gaze into the void. Modigliani never portrays his companion in men’s clothing, as with the numerous femmes garçonnes in his oeuvre. Her casual turtleneck sweater, on the other hand, recalls student garb of the 1960s or 70s.

Modigliani once again falls ill to tuberculosis, more seriously than ever. Back in Paris, he dies on January 24, 1920, at the age of only thirty-five. The next day Jeanne, seeing no hope for the future, takes her own life.

Struck down by death at the moment of glory

This horrific end casts a long shadow across Modigliani’s oeuvre — even as his works are finally beginning to gain notoriety in Paris and even London and the artist is beginning to enjoy success. Be that as it may, the unconventional women Modigliani portrayed so sensually and seriously reveal just how far ahead of his time he really was.