Monet

Claude Monet (1840–1926) was an early and persistent champion of plein air painting, preferring to work outdoors and directly in front of the motif. Key to his artistic vision was the exploration of real places in situ, which required him to respond spontaneously to uncontrollable factors such as weather and light.

His aim was to capture fleeting sensory impressions in an authentic and immediate manner. In this digital prologue to our large-scale Barberini retrospective, we take a brief look at some of the key places that inspired Monet’s Impressionist plein-air painting.

I only know that I do what I can to render what I feel when facing nature and that more often than not, when I try to do so, I completely forget the most basic rules of painting, if indeed there are any.

The Beach at Trouville, 1870, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford

Photo: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Allen Phillips

Monet gained his first experience of outdoor painting in Normandy, the northernmost region of France, which quickly established itself as a hot-spot of the burgeoning seaside tourism in the middle of the 19th century.

The Beach at Trouville is one of his best-known early works. It was executed in 1870, while Monet was on honeymoon with his first wife, Camille. Despite the remarkably free brushwork at play here, the artist rendered the hotels on the right with a keen eye for architectural details. Such an approach was typical of Monet, who always wanted to depict a place’s topography with as much precision as possible.

Apart from Normandy, another place that played a key role in Monet’s early work was the Forest of Fontainebleau.

SIK-ISEA, Zurich/Jean-Pierre Kuhn

Forest of Fontainebleau, 1865, Kunst Museum Winterthur, gift of the Galerieverein, 1934

This natural woodland lay south of Paris had already been explored in the first half of the 19th century by artists of the so-called Barbizon School. It was a popular destination for tourists and had widely been documented by famous photographers. Like his scenes from Normandy, Monet’s paintings of Fontainebleau were aimed at the at affluent bourgeois viewers, whose lifestyle was increasingly defined by travel, leisure and recreation – key themes of his Impressionist painting.

In the second half of the 19th century, the city of Paris had been radically restructured and modernized. With its wide boulevards and sun-drenched parks, the French capital provided the Impressionists with a wealth of welcome new motifs.

Leisurely strolling or flânerie was in fashion, as city dwellers began to spend their spare time in public spaces. In his views of Paris, Monet focussed on a complex interplay of urban architecture, gardens full of light and people engaged in simultaneous activities. He captured each moment with striking painterly freedom.

Railways play an important role in Monet’s art.

The rapidly expanding rail network allowed him to seek out different types of landscape all over France – from the windswept Atlantic coastlines in the north to the light of the southern Riviera. Working en plein air was additionally facilitated by the portable easel box and industrially manufactured oil paints in handy tin tubes with resealable lids.

The Seine at Argenteuil, 1875, private collection

Argenteuil

In 1871 Monet, his wife Camille and their son Jean moved to Argenteuil – a suburb of Paris that was known for its sailing regattas and imposing bridges. For Monet’s artistic tributes to the modern age, this picturesque little town, a popular destination for day trippers, presented a wealth of motifs. Above all, he painted the activities unfolding around the idyllic riverside: walking, sailing and rowing along the Seine. During the seven years he lived in Argenteuil, Impressionism established itself as France’s leading avant-garde movement.

The Seine, I have painted it all my life, at every time of day, in every season. From Paris down to the sea. I have never tired of it: to me it is always new.

By the Bridge at Argenteuil, 1874, Saint Louis Art Museum

Vétheuil

In late 1878 Monet moved to Vétheuil, a sleepy medieval village on the Seine some 65 kilometres north-west of Paris. The rustic surroundings of this remote community led to a turning-point in his art. While he had thus far favoured quintessentially modern, contemporary subjects, he now he focused on pure landscapes and timeless rural idylls. Among his best-known works of this period are his depictions of the so-called debacle – the break-up of ice on the river Seine, which had frozen over in the extremely cold winter of 1880. The series was executed a few months after Camille died of abdominal cancer at the age of 32.

Melting of Floes at Vétheuil, 1880, Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, on permanent loan to the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Giverny

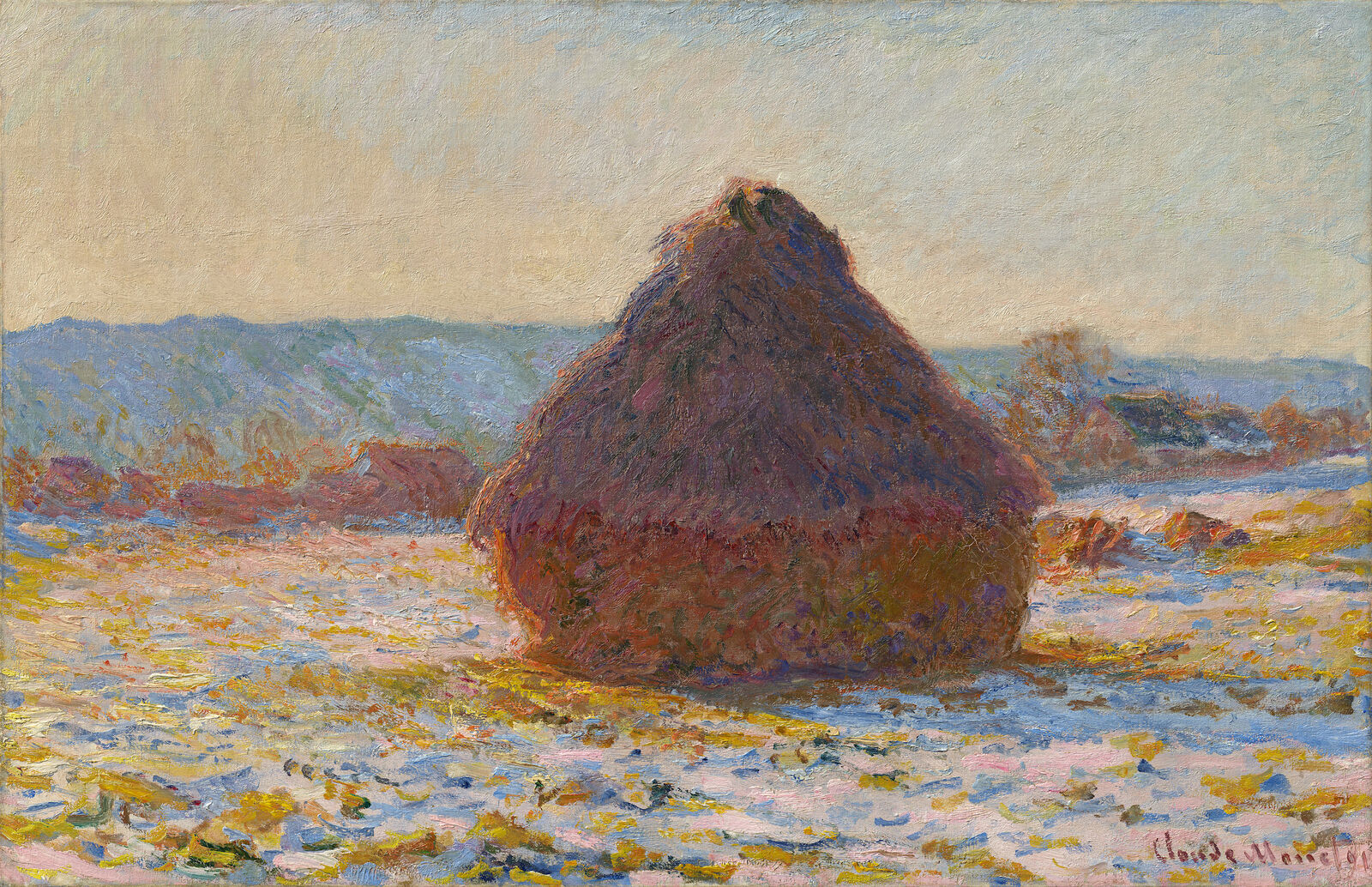

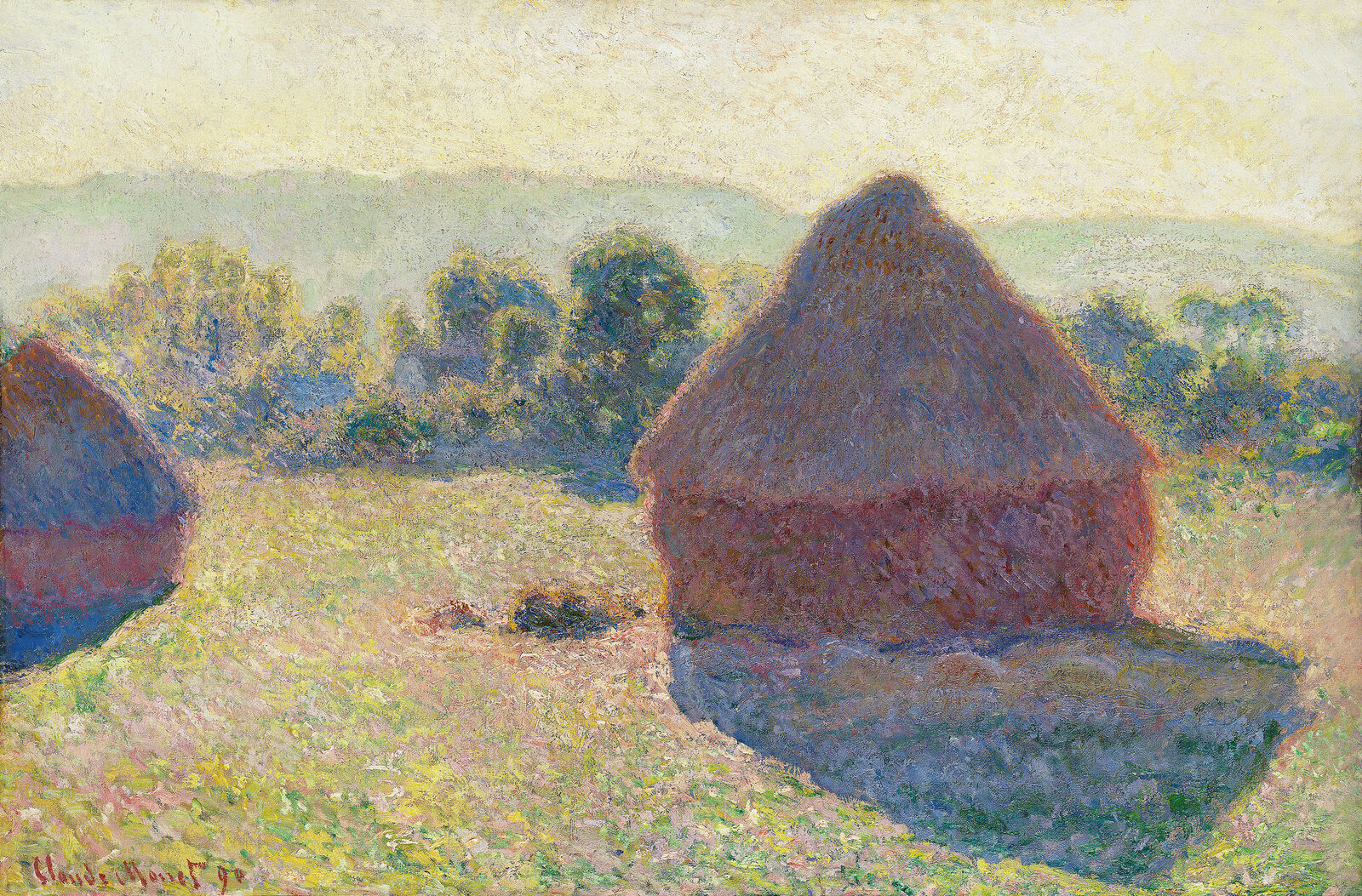

After Camille’s untimely death, Monet began a relationship with Alice Hoschedé, the former partner of one of his major early collectors. In 1883 he moved with her to Giverny, a little farming village in Normandy that was to remain his home until his death in 1926. In his paintings of this area, he surveyed the landscapes around the fertile valley of the Seine, studying rows of tall poplar trees and meadows lush with vegetation. With his depictions of the Grainstacks he developed his famous serial approach, painting countless variations that showed the very same motif in different conditions of both weather and light.

Grainstack in the Sunlight, Snow Effect, 1891, Hasso Plattner Collection

Grainstacks in the Sunlight, Midday, 1890, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

In my view a landscape does not exist in itself, because its appearance is changing all the time; it lives through what encases it the air and the light that keep altering. (…) For me the subject only acquires its true value from what surrounds it.

Claude Monet: Rocky Coast and the Lion Rock, Belle-Île, 1886, Des Moines Art Center

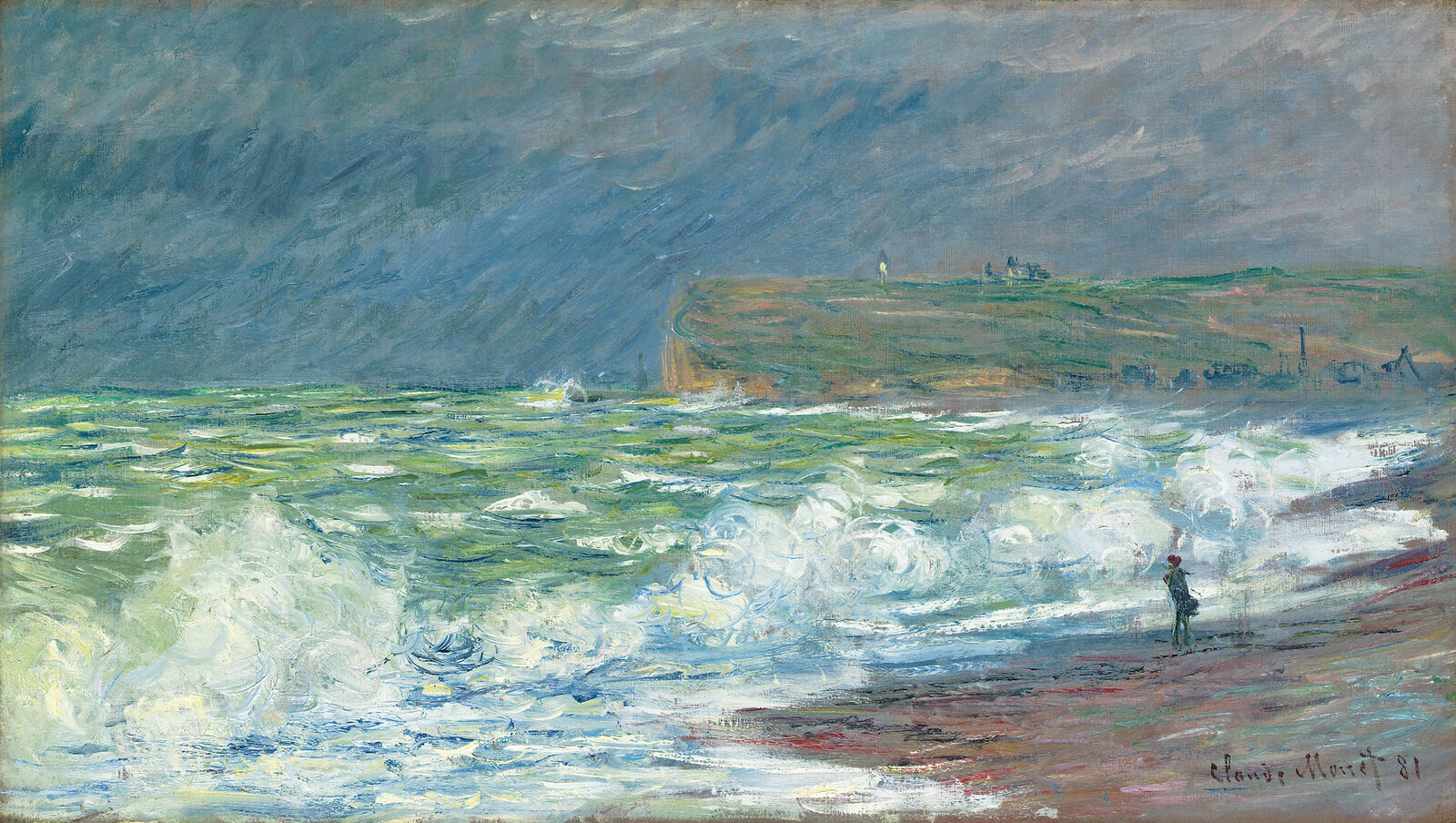

Monet was fascinated by the rugged Atlantic coast in northern France. As the 19th century drew to a close, the view from the cliffs towards the horizon across the wind-tossed sea revived the experience of the sublime which the painters of Romanticism had associated with the primeval power of the sea.

Many of Monet’s coastal scenes suggest an otherworldly, mystical contemplation of nature. In this respect they reflect this region’s highly idealised image as a remote haven as yet untouched by modern progress.

For his landscapes Monet often chose sights that were popular with tourists and symbolic landmarks of the region. In Étretat he frequently painted the Porte d’Aval and the Aiguille – striking rock formations that resembled a tall arch and a needle. In his serial views of these cliffs, Monet strategically shifted from one angle to another. This enabled him to fully exploit the compositional potential, which the the spatial interplay between the two structures offered.

The Beach at Fécamp, 1881, private collection

I was unperturbed by the waves that lapped around and died away a few paces from me. In short, so thoroughly absorbed was I that I failed to see an enormous wave that flung me against the cliff, and I was cast into the foam with all my equipment!

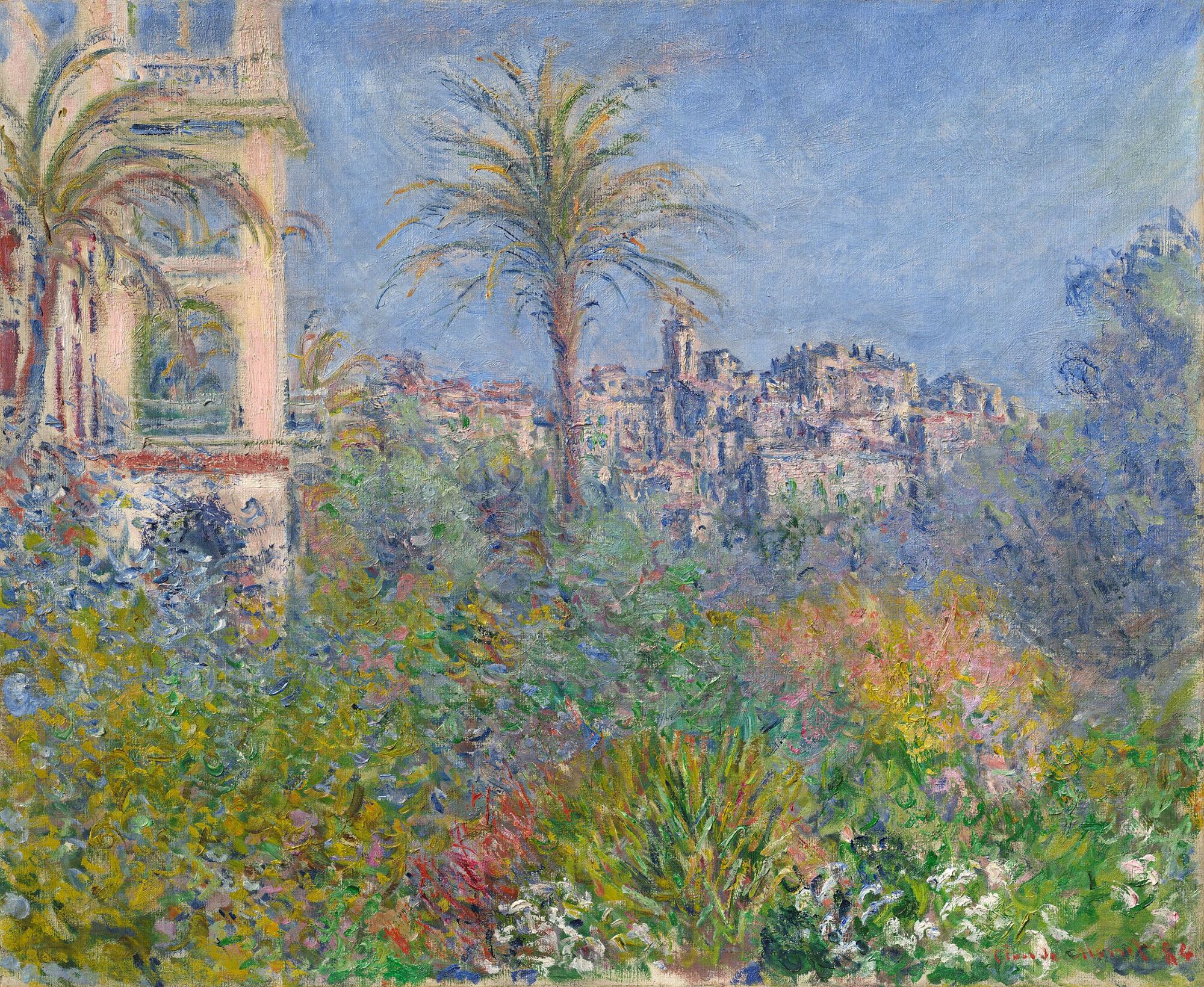

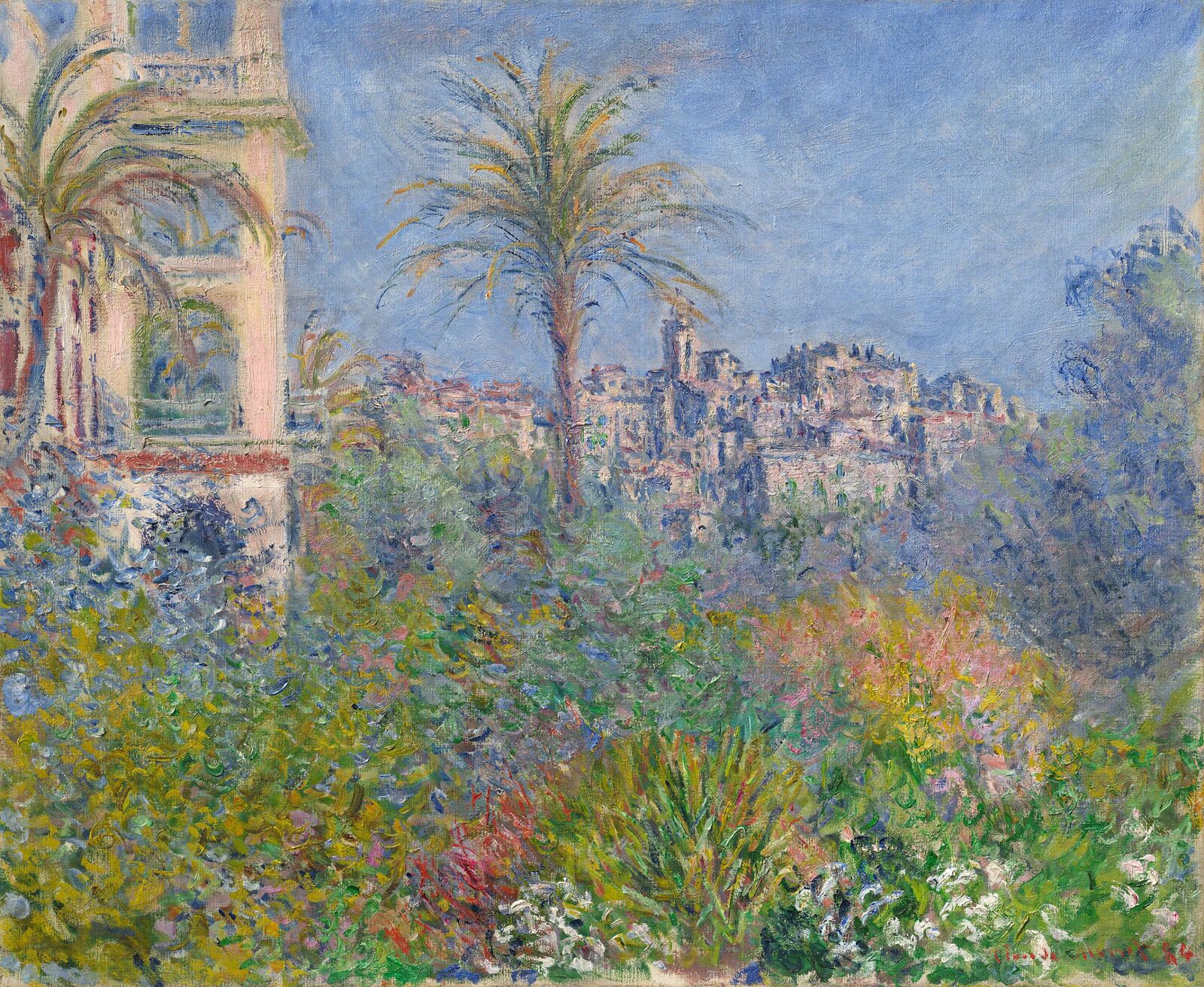

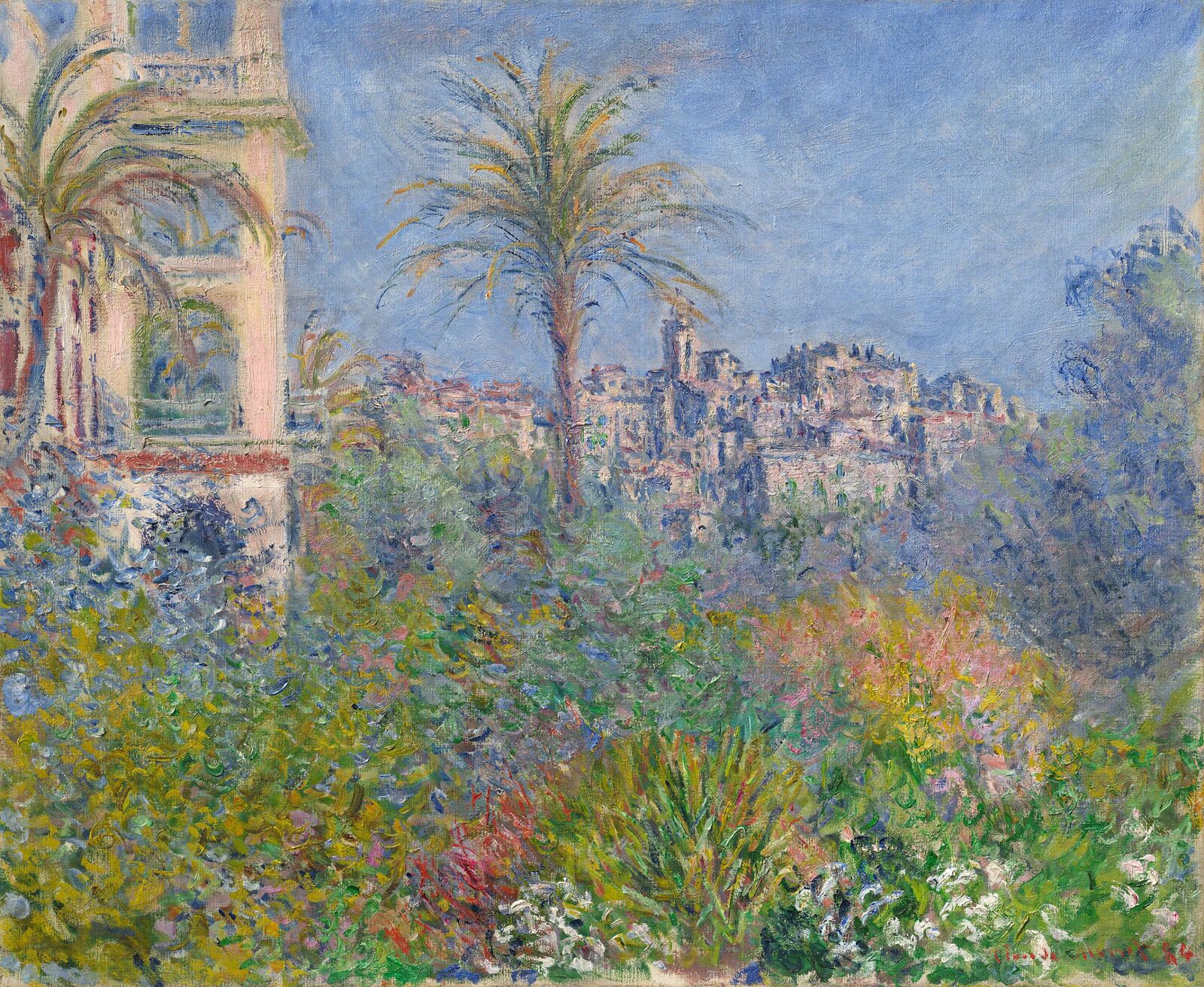

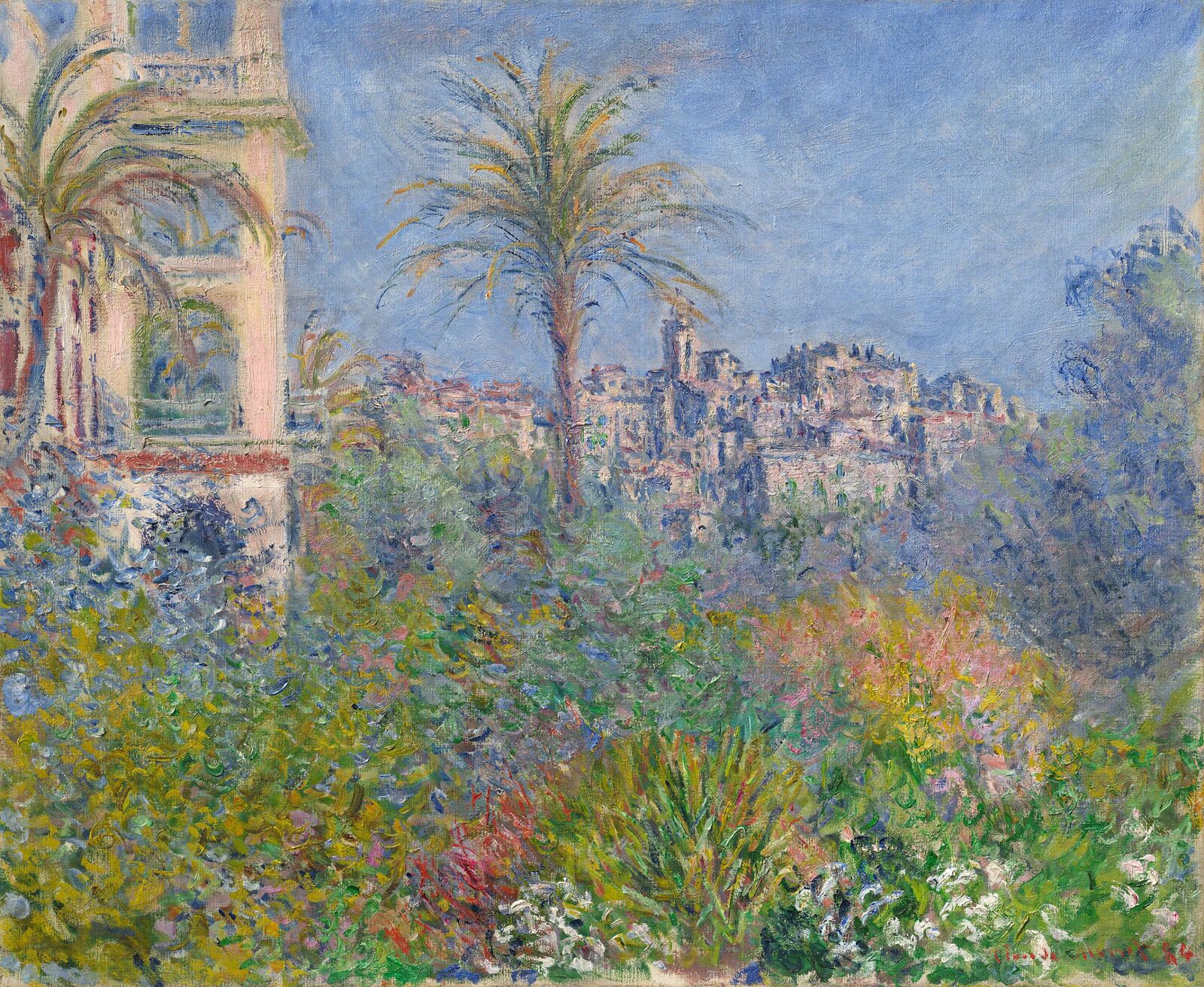

Claude Monet, Villas in Bordighera, 1884

Hasso Plattner Collection, Museum Barberini

In 1884 and 1888 Monet embarked on two longer painting stints to the Mediterranean. The bright colors and lush vegetation of popular travel destinations such as Bordighera and Antibes inspired him to paint numerous sun-drenched scenes of this earthly paradise.

For an artist accustomed to the cool tonality of Normandy, the piercing Riviera light came as a welcome change. He wrote enthusiastically to his friend Théodore Duret that he would need a palette of diamonds and sparkling precious stones to do justice on canvas to the jewel-like colours around him.

These palm trees will be the death of me; besides, the motifs are extremely difficult to capture, to place on the canvas; everything is so dense (…) but when one looks for motifs it is very difficult. I would like to do some orange and lemon trees standing out against the blue sea, but I cannot find any the way I want them. As for the blue of the sea and the sky, impossible!

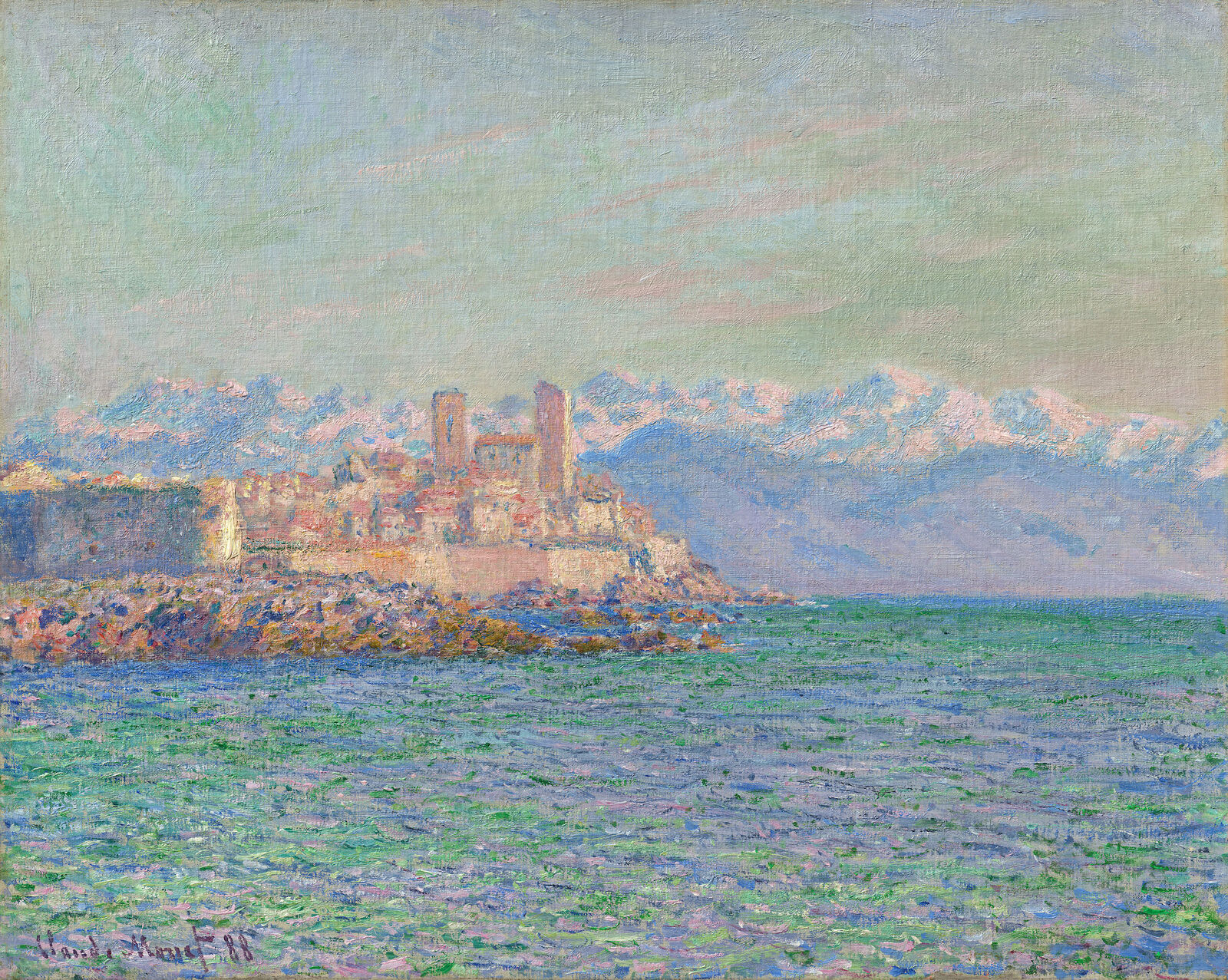

The Fort of Antibes, 1888, Hasso Plattner Collection

In his letters Monet often describes the need to obtain a sense of a new landscape, to find his way around an unknown area before he can begin translating it into paint. He often felt his way forward gradually by trying to depict a motif from different angles. In his views of Antibes too, he captured the old town from a variety of perspectives.

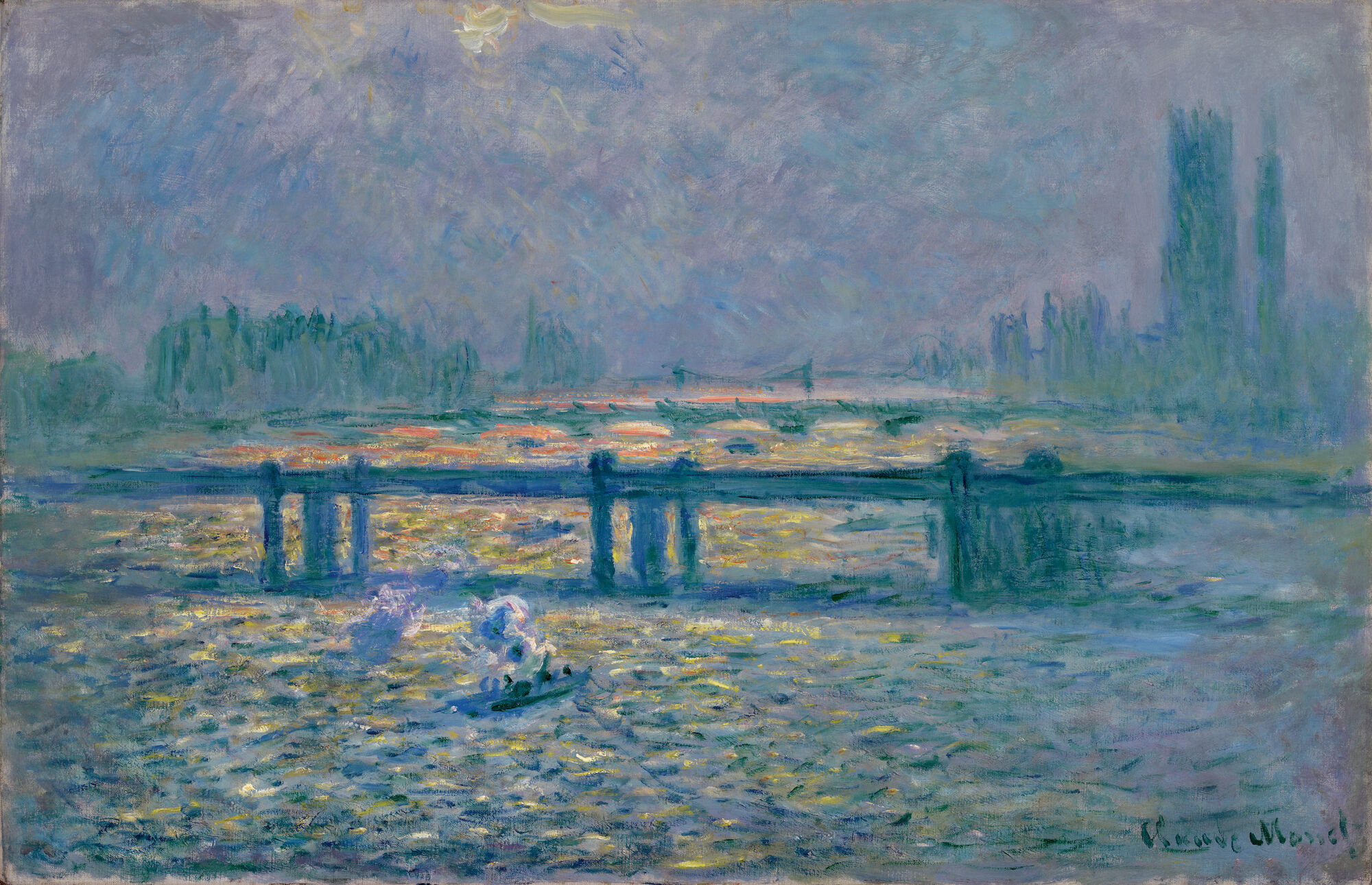

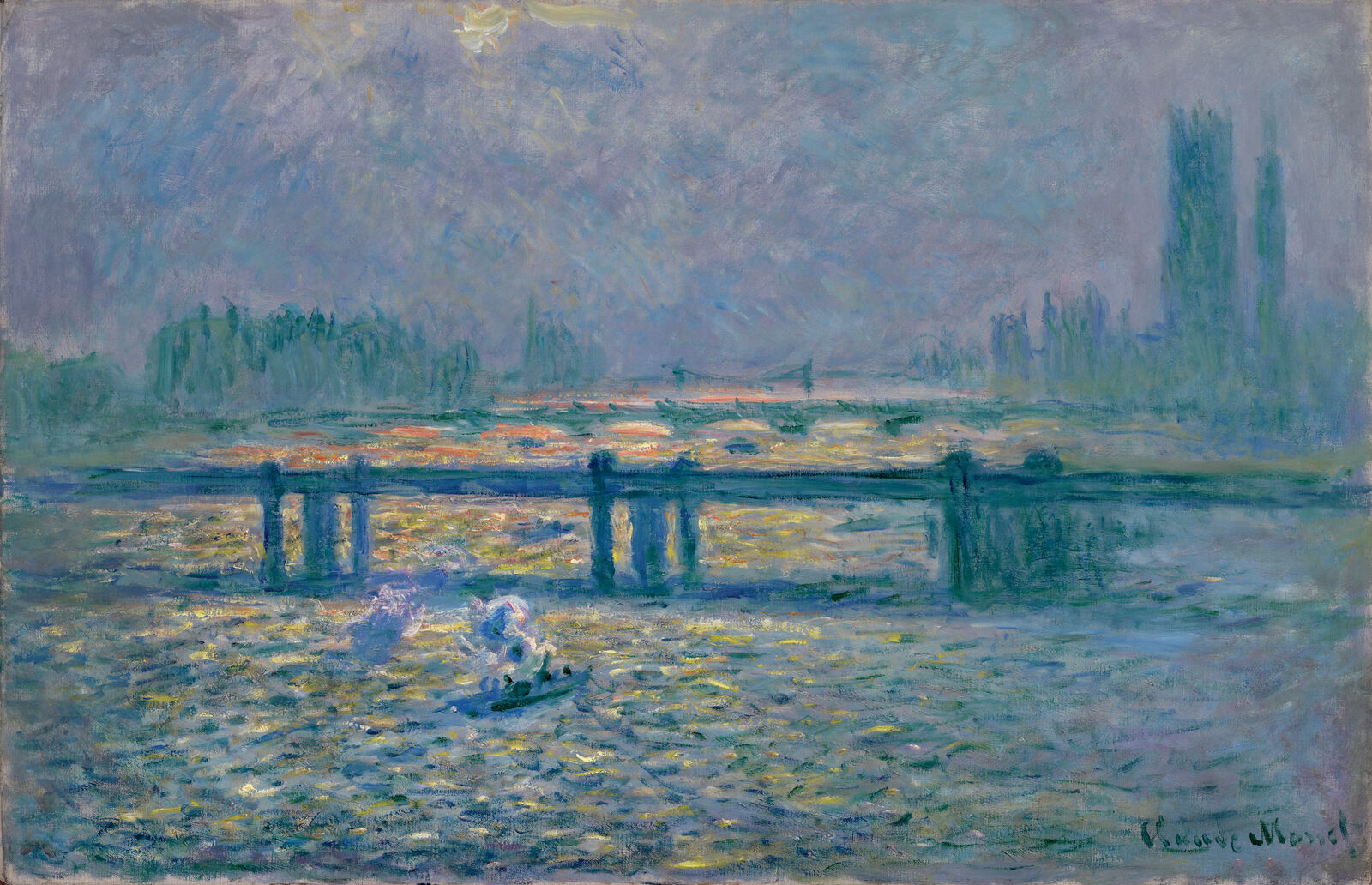

Charing Cross Bridge, Reflections on the Thames, 1899–1901, The Baltimore Museum of Art

Mitro Hood

For three consecutive winters from 1899, Monet spent several weeks in London, which he had already visited in the early 1870s.

His best-known depictions of the British capital include views of Waterloo and Charing Cross Bridge. The combination of water, fog and modern stone architecture was an ideal projection screen for his exploration of the most subtle effects of color and light. Because of the constantly changing weather, Monet kept his paintings of the Thames bridges in the state of unfinished oil sketches, which he reworked and completed back in his studio in France.

Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect, 1903, Denver Art Museum

What I like most of all in London is the fog. (…) Without the fog London would not be a beautiful city. It is the fog that gives London its magnificent breadth.

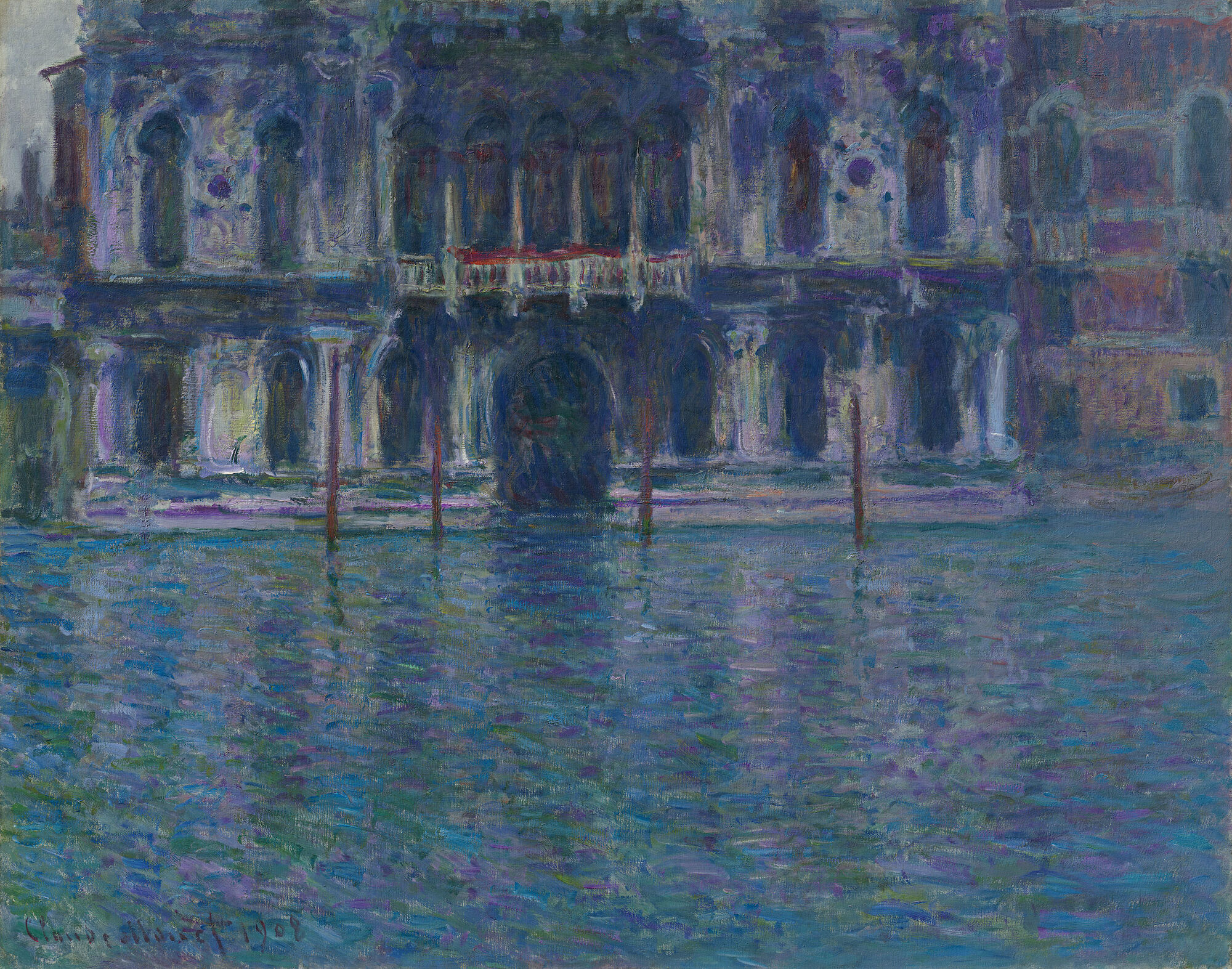

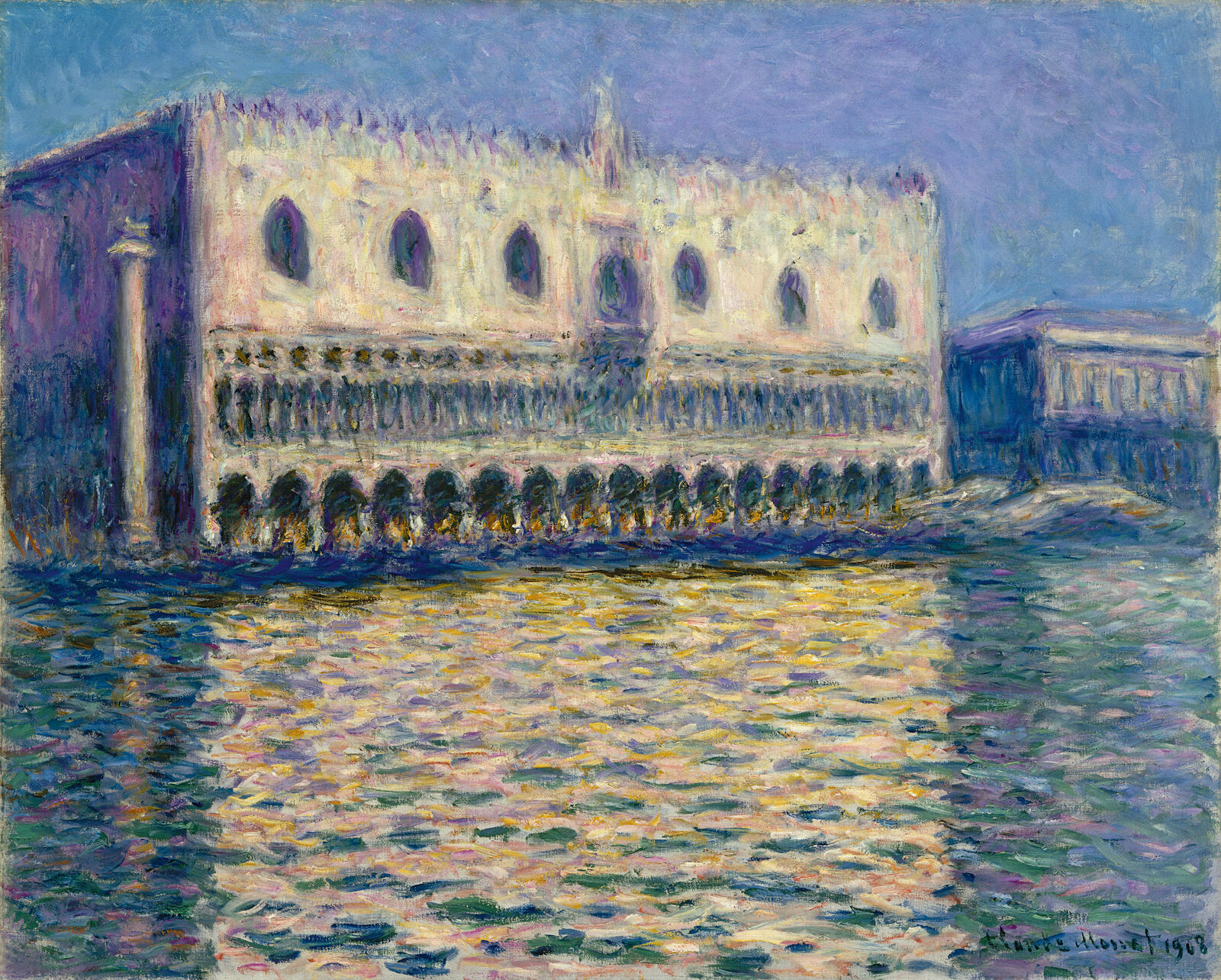

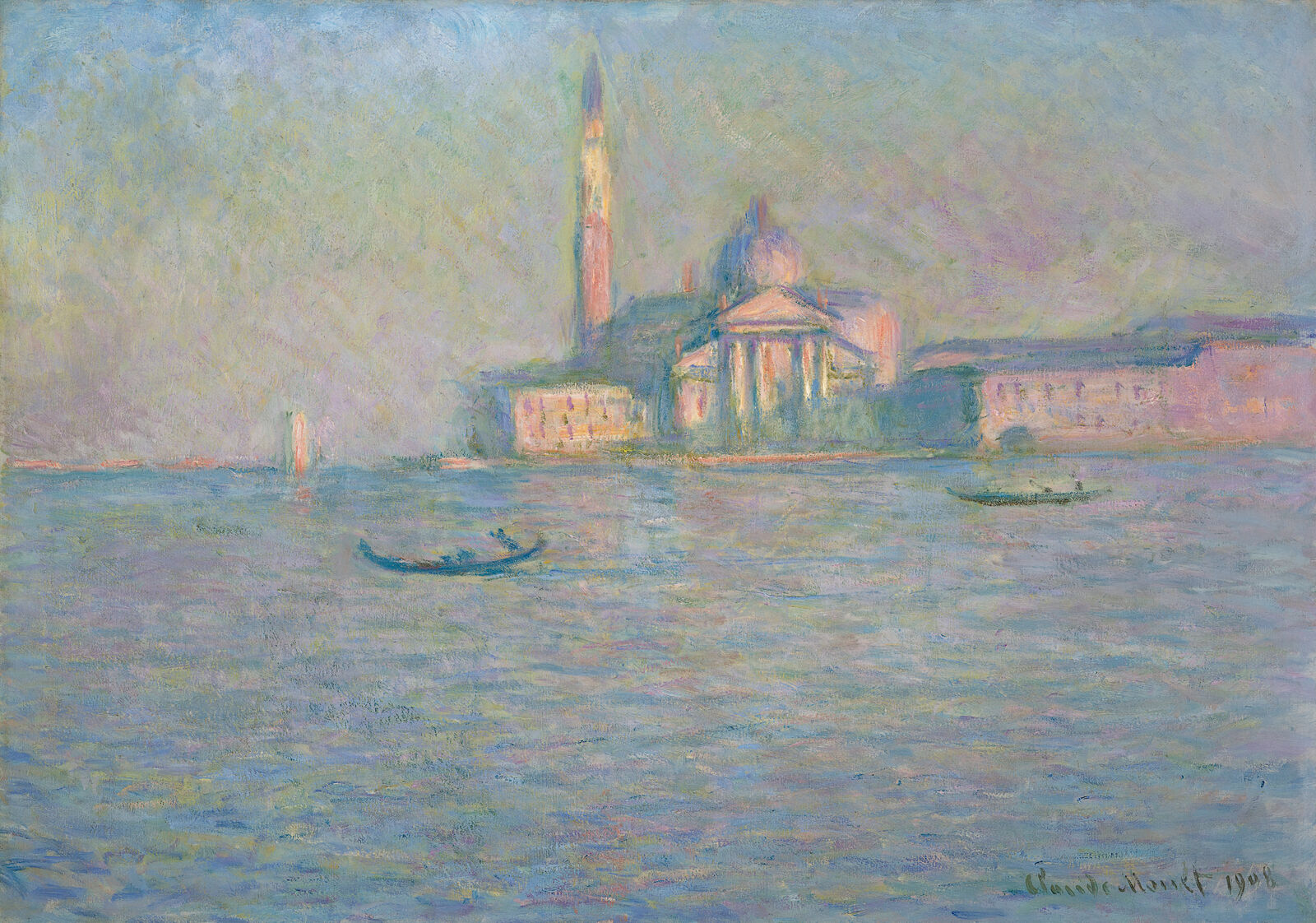

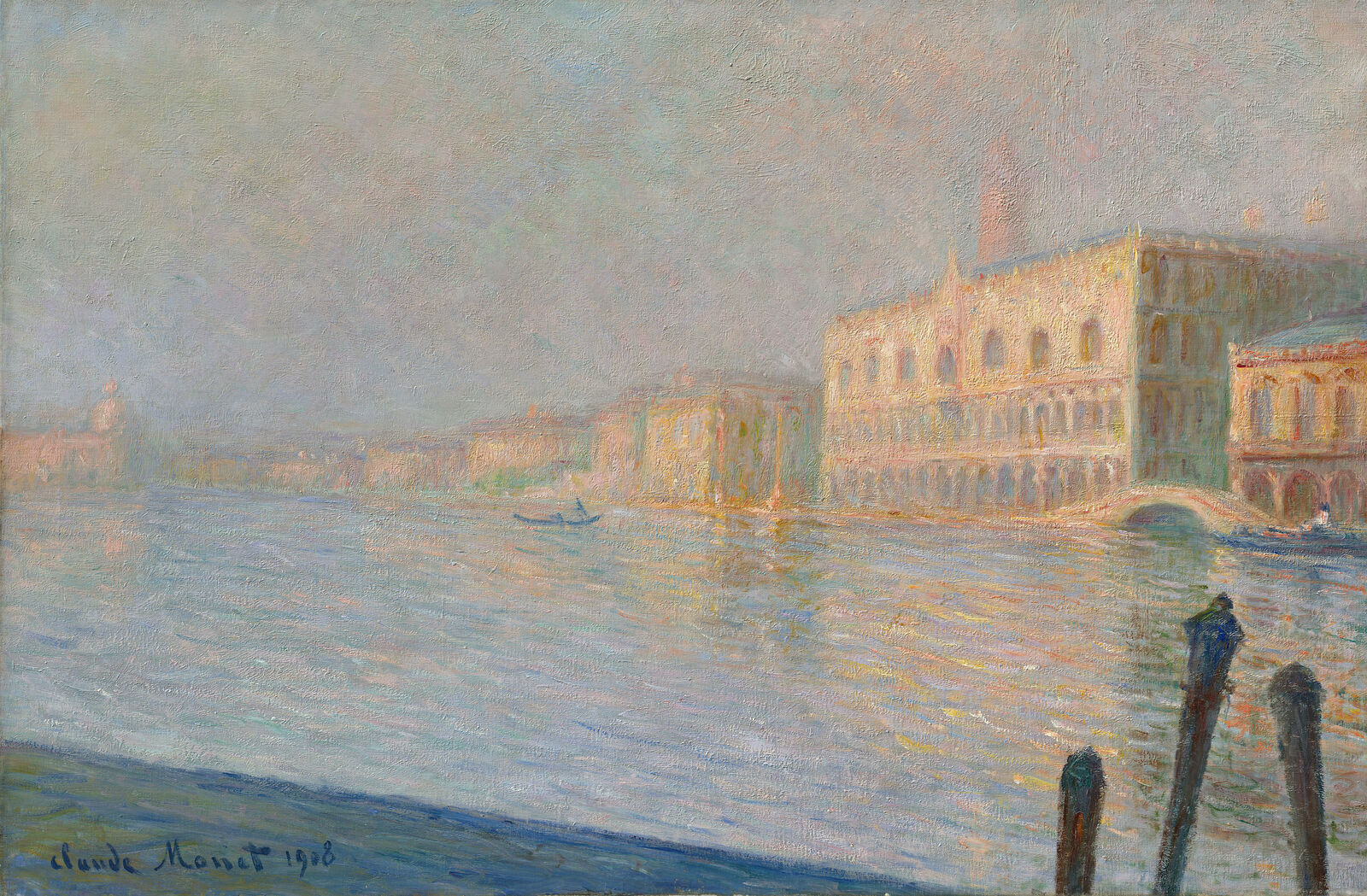

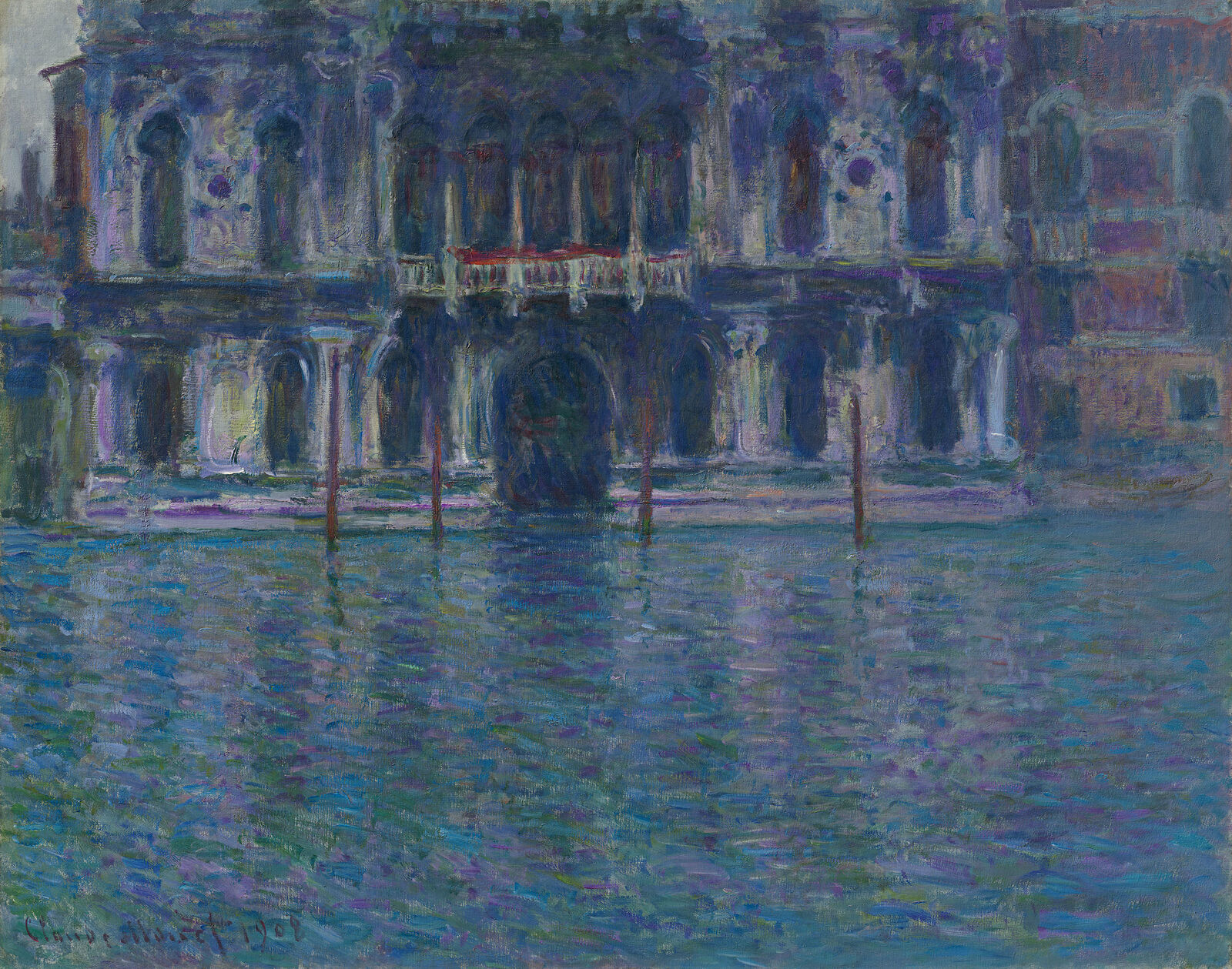

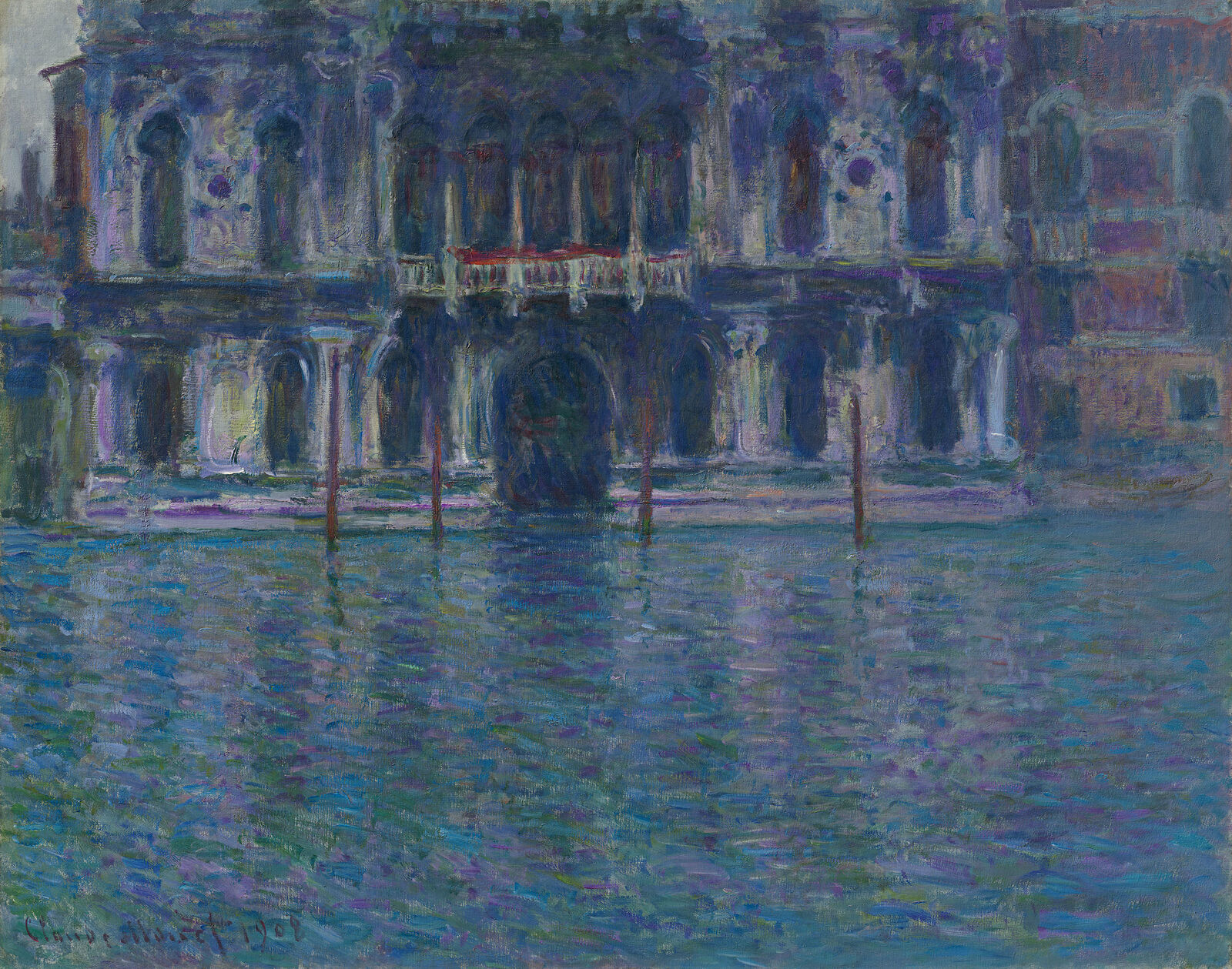

The Palazzo Contarini, 1908, Hasso Plattner Collection

Together with his wife Alice Monet spent several weeks of autumn 1908 in Venice – a city with an almost unmatched record of intriguing generations of artists before him.

Like in London, he there focused here on the momentary interplay of striking architectural structures and colorful reflections produced by flickering light dancing on the surface of the water. The iridescent hues and mysterious flows of color endow his Venetian vistas with a remarkably dream-like, oneiric atmosphere.

Simple-minded scribblers and painters had torn Venice away from nature. Claude Monet came to Venice and brought nature back.

The Rio della Salute, 1908, Hasso Plattner Collection

What a shame I did not come here when I was younger and entirely undaunted! Ah well… But I have spent some delightful moments here, almost forgetting I was the old man I am.

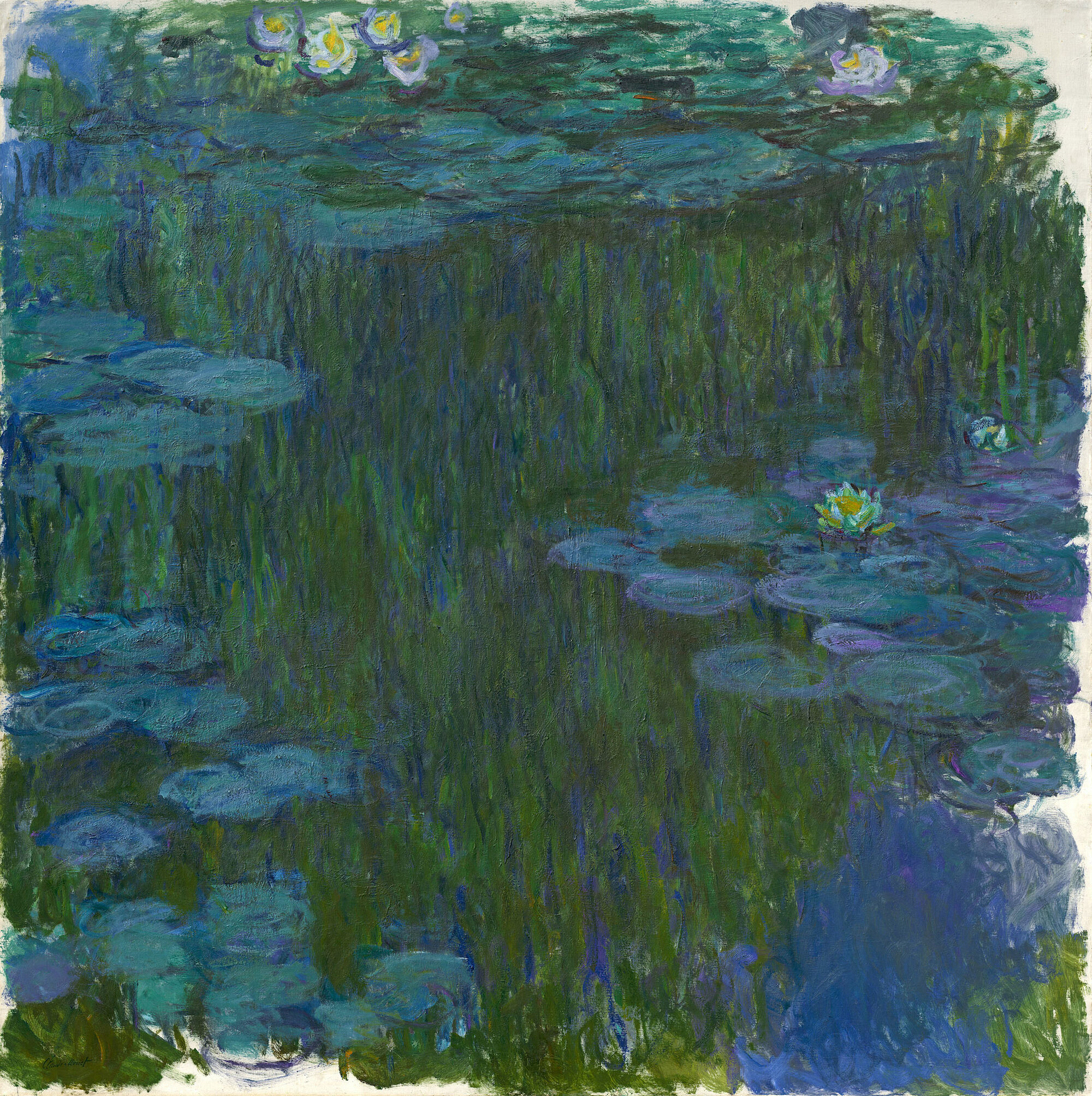

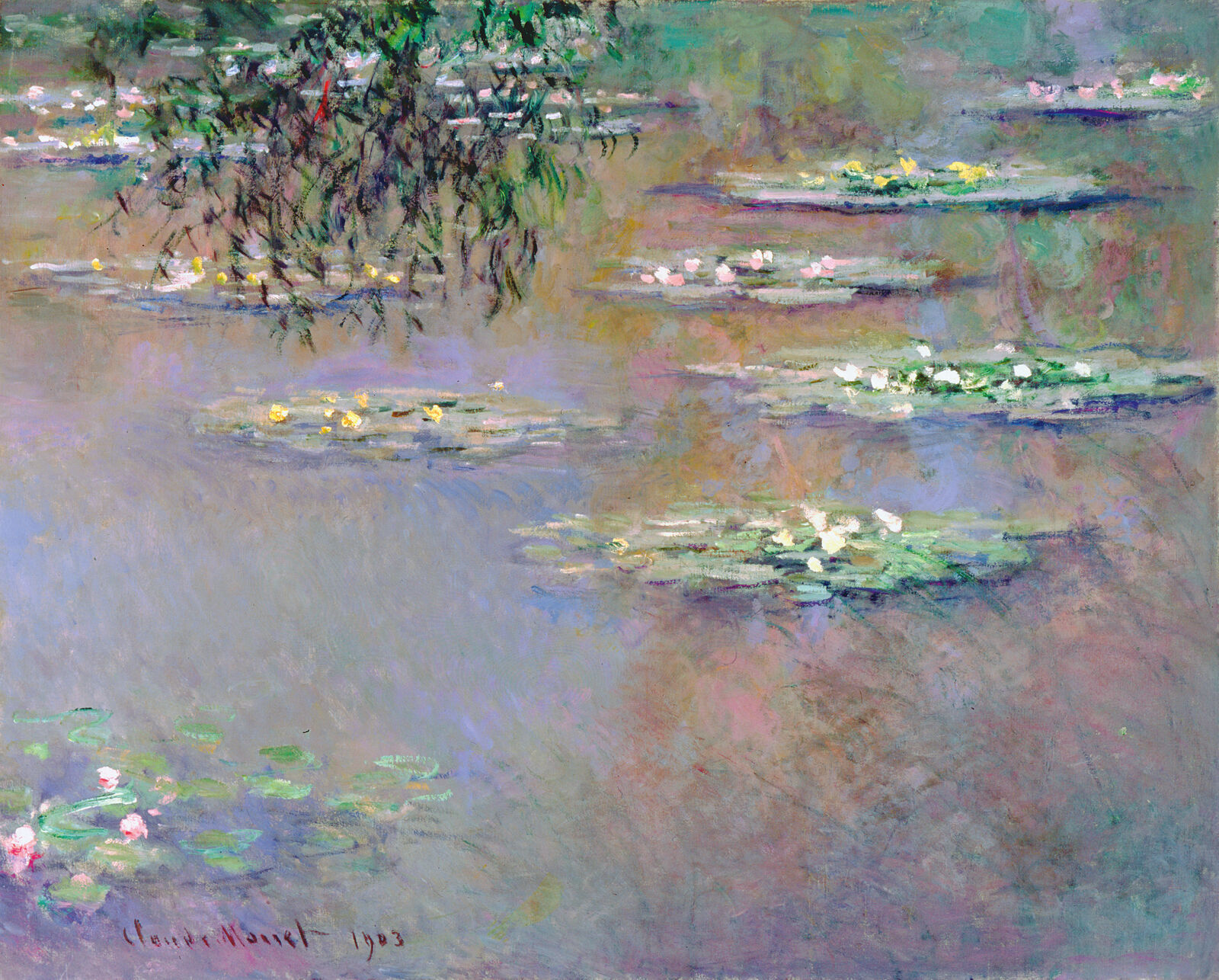

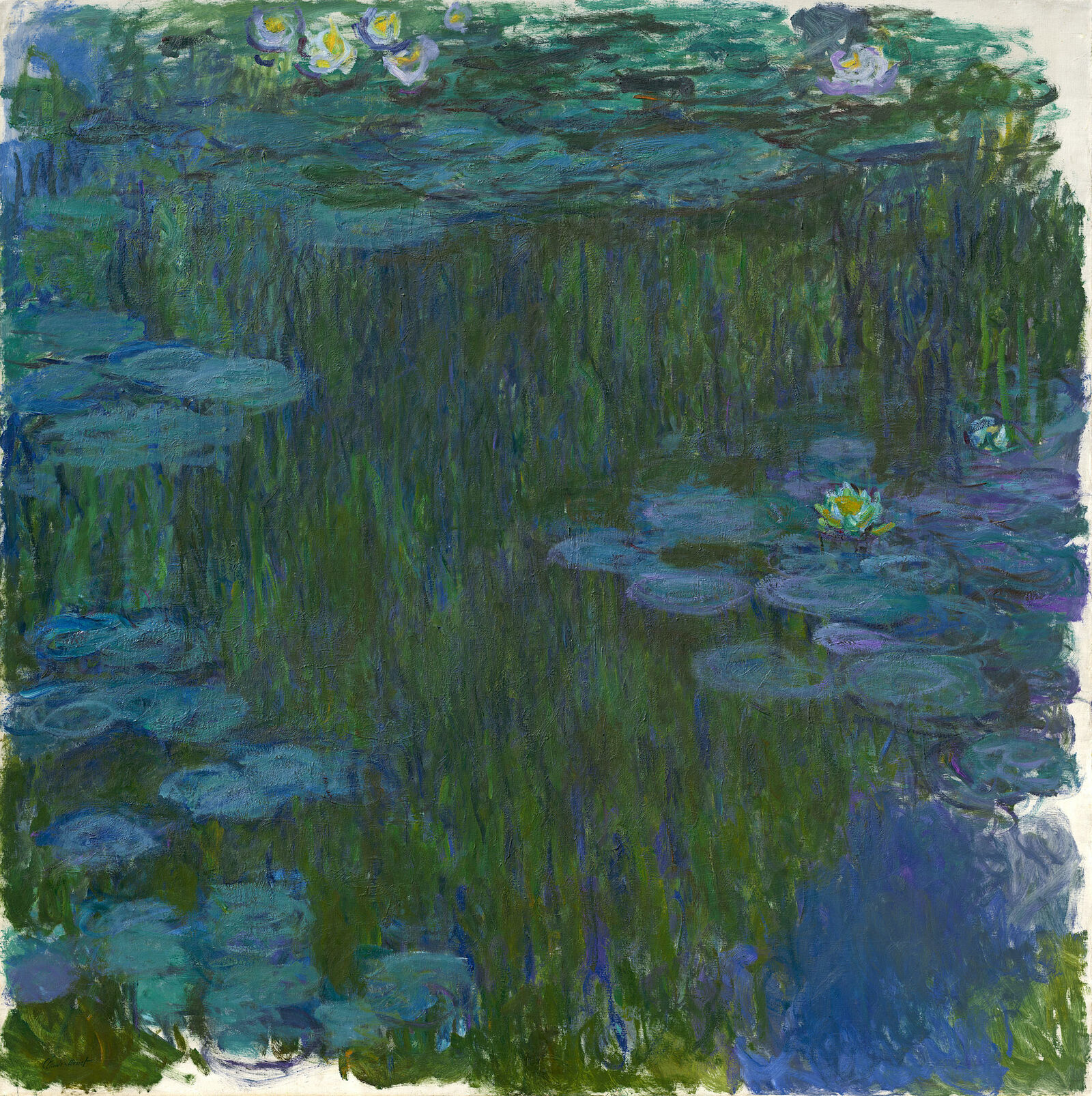

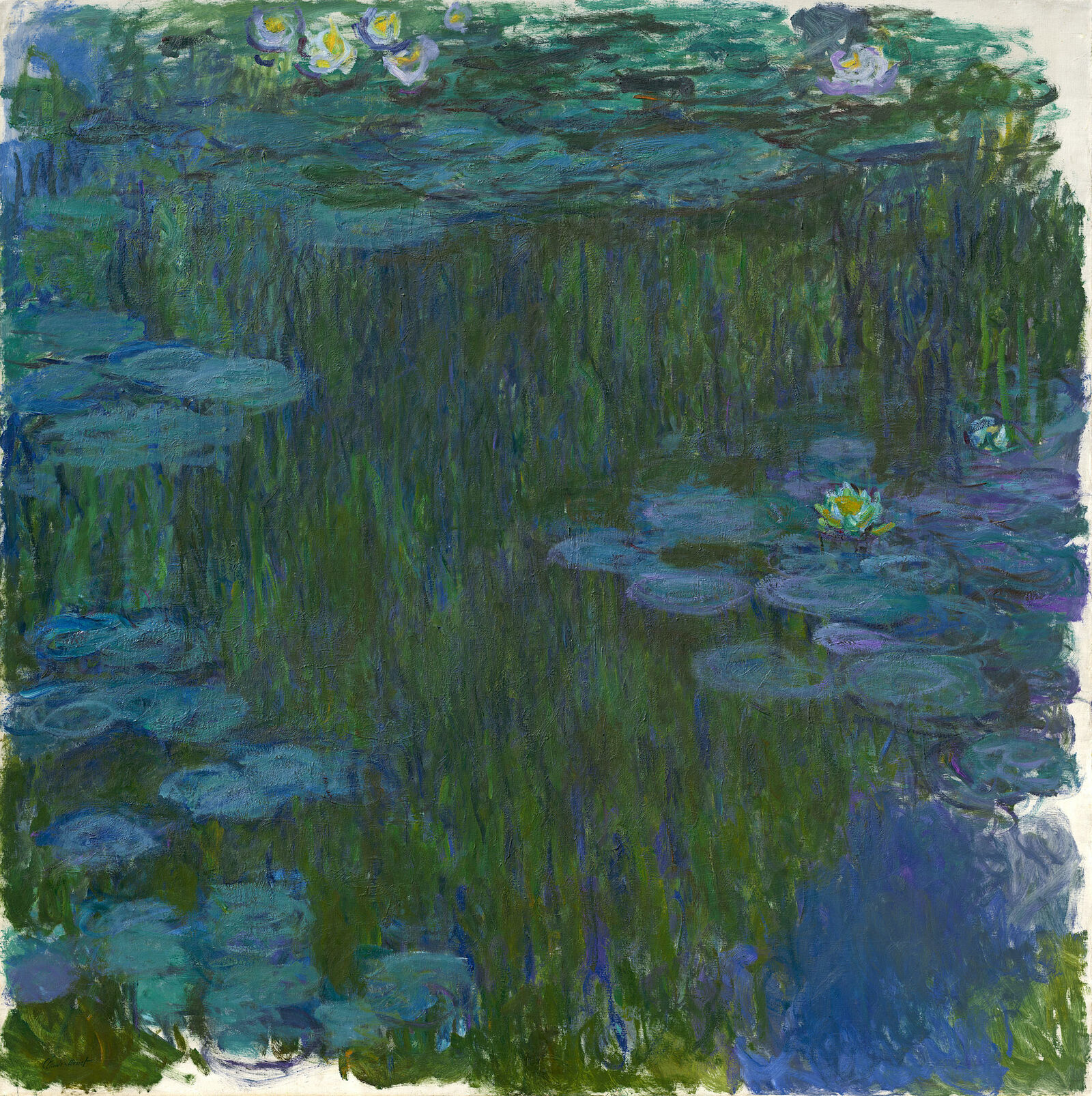

Water-Lilies, 1914–1917, Hasso Plattner Collection

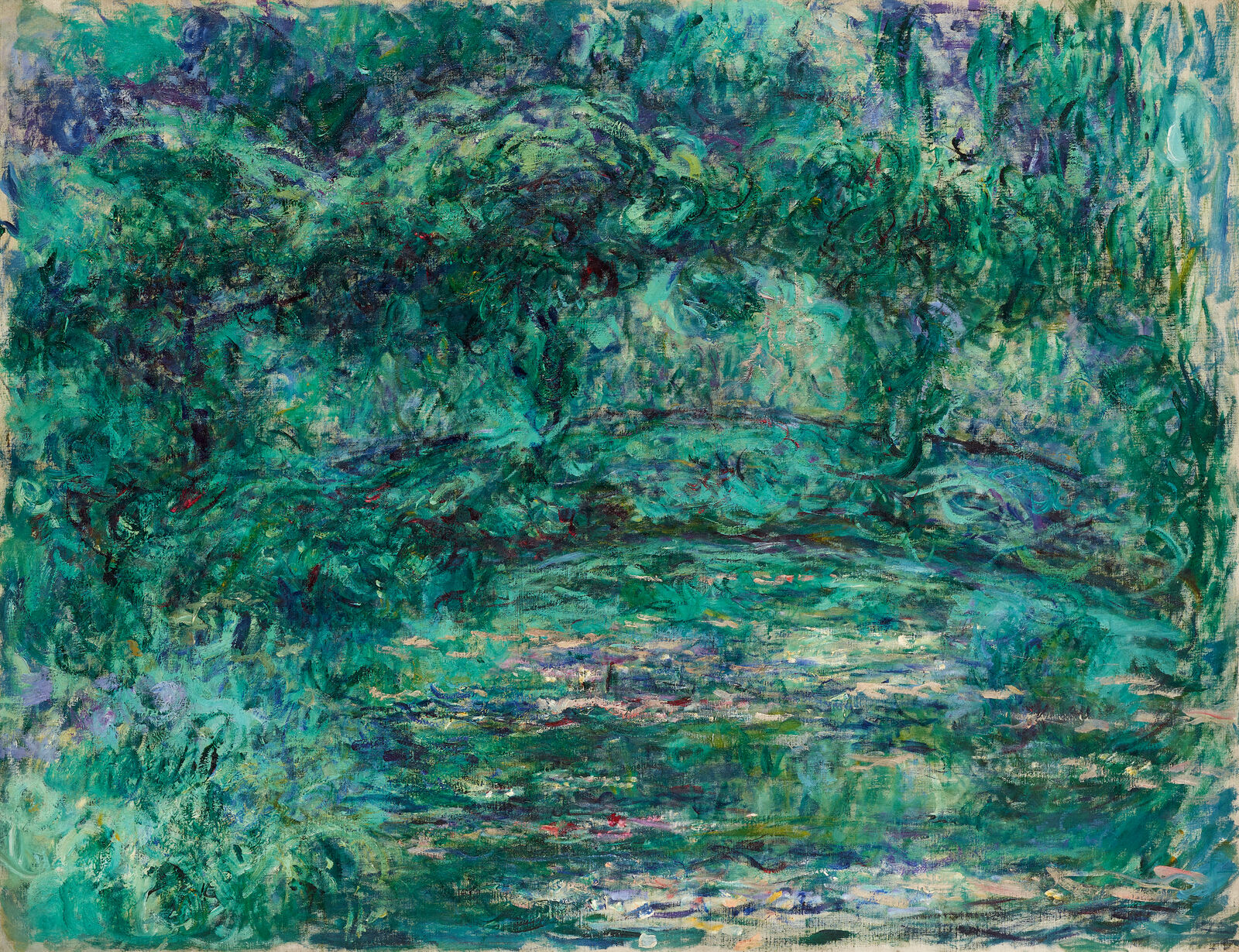

In the 1890s Monet had an opulent water garden laid out for his home in Giverny.

The heart of this landscape was an artificial pond of water-lilies crossed by a wooden bridge in the Japanese style. This elaborate backdrop in Monet’s self-created paradise transcended the category of natural landscapes in his art. This exotic environment was to become the almost exclusive focus for his late work.

It took me a long time to understand my water lilies. I planted them simply for pleasure; put them in without a thought for painting them. One does not discover a landscape in a single day. And then, quite suddenly, the magic of my pond was revealed to me. I picked up my palette. (…) Ever since then I have hardly touched another motif.

The catalogue raisonné of Monet’s œuvre lists about 250 depictions of water-lilies.

Today these works are among his best-known compositions and have become the very epitome of Impressionist art. The expressive coloring and loose brushwork of these paintings made Monet one of the main precursors of abstract art in the early 20th century.

The Water-Lily Pond, ca. 1918, Hasso Plattner Collection

Water-Lilies, 1904, Denver Art Museum

I have no other wish than to mingle more closely with nature, and to live in harmony with her laws (...). Nature is greatness, power and immortality; compared with her, a creature is nothing, an atom.