Van Gogh

“Painting still lifes is the beginning of everything,” Vincent van Gogh told his students. In the few years he was active as an artist between 1881 and his death in 1890, he painted more than 170 still lifes.

Never before has an exhibition been devoted exclusively to this theme. Yet, so much can be learned from a consideration of Van Gogh’s still lifes. The genre reflects his rapid artistic evolution – from his first experiments with sombre colors to his late canvases, full of expressive power and vitality. This journey takes us from the Netherlands via Paris to the South of France, charting the oeuvre of one of the great pioneers of modern painting.

Birds’ Nests, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Carafe and Dish with Citrus Fruit, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Still Life with Cabbage and Clogs, 1881, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Vincent van Gogh was already 27 when he turned to painting in 1880. In 1881, after a year of self-study and drawing exercises, he switched to the brush and palette.

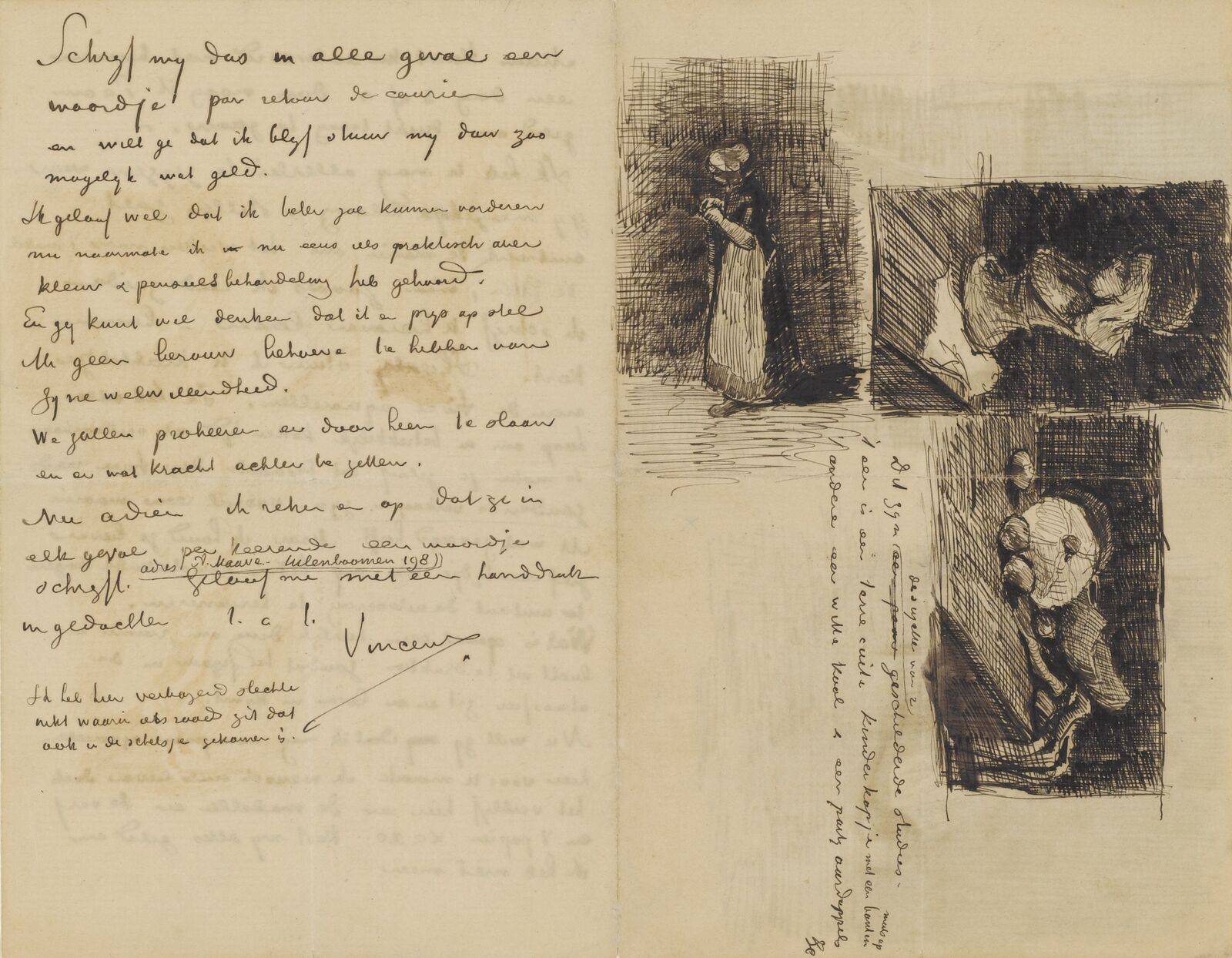

He took lessons from his cousin Anton Mauve, a highly esteemed painter of the Hague School. Still life was a rewarding gateway into his new profession and would always remain a framework for his artistic experiments. Numerous letters from Vincent to his brother Theo van Gogh offer insights into his life and the evolution of his painting.

Vincent an Theo van Gogh, December 1881, The Hague, Letter 192, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Now I’ve come from him [Mauve] with a few painted studies and a couple of watercolours. Of course they aren’t masterpieces and yet I truly believe there’s something sound and real in them, more at least than in what I’ve made up to now. And so I now consider myself to be at the beginning of the beginning of making something serious. […] Theo, what a great thing tone and colour are! And anyone who doesn’t acquire a feeling for it, how far removed from life he will remain! M[auve] has taught me to see so many things I didn’t see before.

Vincent van Gogh: Smoked Herrings, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Van Gogh acquainted himself thoroughly with Dutch 17th-century painting. He visited museums such as the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam to study the great examples.

He especially admired the fresh, powerful chiaroscuro of artists such as Rembrandt or Frans Hals and he painted his own first works in this dark-toned manner of the Dutch masters. Whereas the Old Masters had often celebrated grandeur and exoticism or used symbols to convey a message, Van Gogh depicted simple, everyday items such as fruit and vegetables.

Vincent Van Gogh: Still Life with a Bearded-Man Jar, 1884, Kröller Müller Museum, Otterlo

Floris Gerritsz. van Schooten: Still Life with Herrings, Oysters, and a Pipe, ca. 1625, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem

Vincent van Gogh: Still Life with Vegetables and Fruit, 1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

In his first still lifes from the period until 1885, Van Gogh focused on objects associated with everyday life in the country: household utensils and, depending on the season, natural produce such as apples, pears, pumpkins or potatoes.

He confined his palette to a few muted tones, mostly shades of brown to which he occasionally added red or green. Initially, he explored the spatial relationship between the objects, but he soon began to address contrasts and nuances of colour.

Still Life with Apples and Pumpkins, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

I made my studies specifically as gymnastics, to fall and to rise in tone.

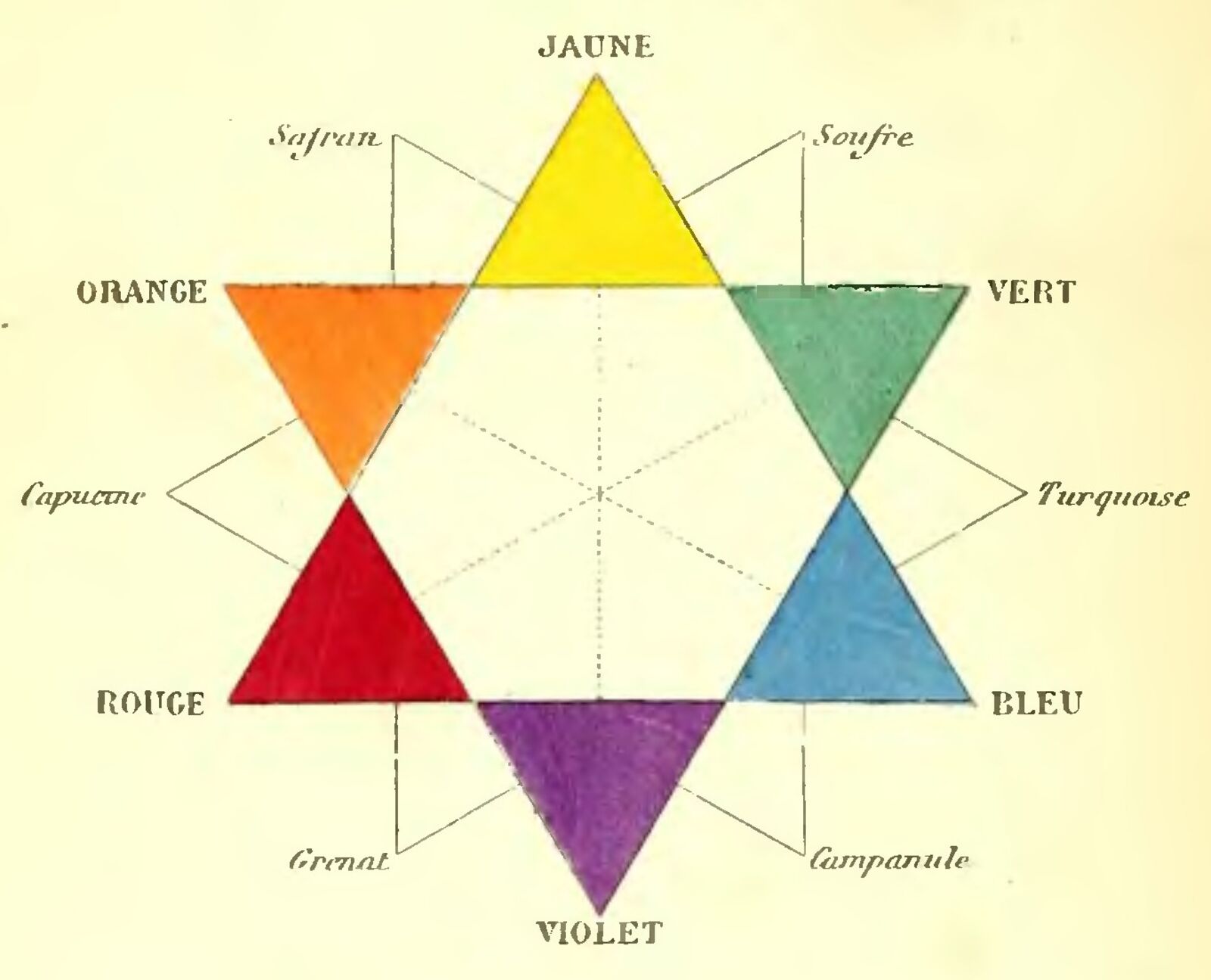

Farbkreis, in: Charles Blanc: Grammaire des arts du dessin. Architecture, sculpture, peinture, 3. Aufl., Paris 1876

Van Gogh read up on the latest 19th-century colour theories in textbooks written by specialists.

Charles Blanc’s Grammaire des arts du dessin (1867), which describes the phenomenon of simultaneous contrasts, made a powerful impression on him. Blanc states that the impact of tones at opposite points of the colour wheel is mutually reinforced by placing them directly next to each other. In his still lifes from 1885, Van Gogh practised no longer describing the shapes of things with lines, but modelled them instead with paint and shades of colour.

Vincent van Gogh: Roses and Peonies, 1886, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

When he moved to Paris in 1886, Van Gogh left not only the Netherlands behind, but also earthy tones and themes drawn from rural peasant life.

In the two years he spent in the French capital, he developed a lighter, richer palette and a personal style. He paved the way for this artistic breakthrough in his floral still lifes, of which he executed more than 30 while in Paris. The motif gave him an opportunity to maintain his links with nature in this new urban setting.

I have made a series of colour studies in painting simply flowers, red poppies, blue corn flowers and myosotys, white and rose roses, yellow chrysantemums.

The stylistic diversity of Van Gogh’s Parisian floral still lifes demonstrates how rigorously he used these canvases to experiment with different painterly techniques.

After working with dramatic contrasts of light and dark, he moved on to serene displays of brightness and colour. He drew input from studies of flowers by contemporary painters such as Adolphe Monticelli, Claude Monet and Édouard Manet. Flower painting was extremely popular in Paris at the time: middle-class buyers liked to hang the decorative motifs on their walls. Van Gogh, too, hoped this choice of subject-matter would make it easier to sell his work.

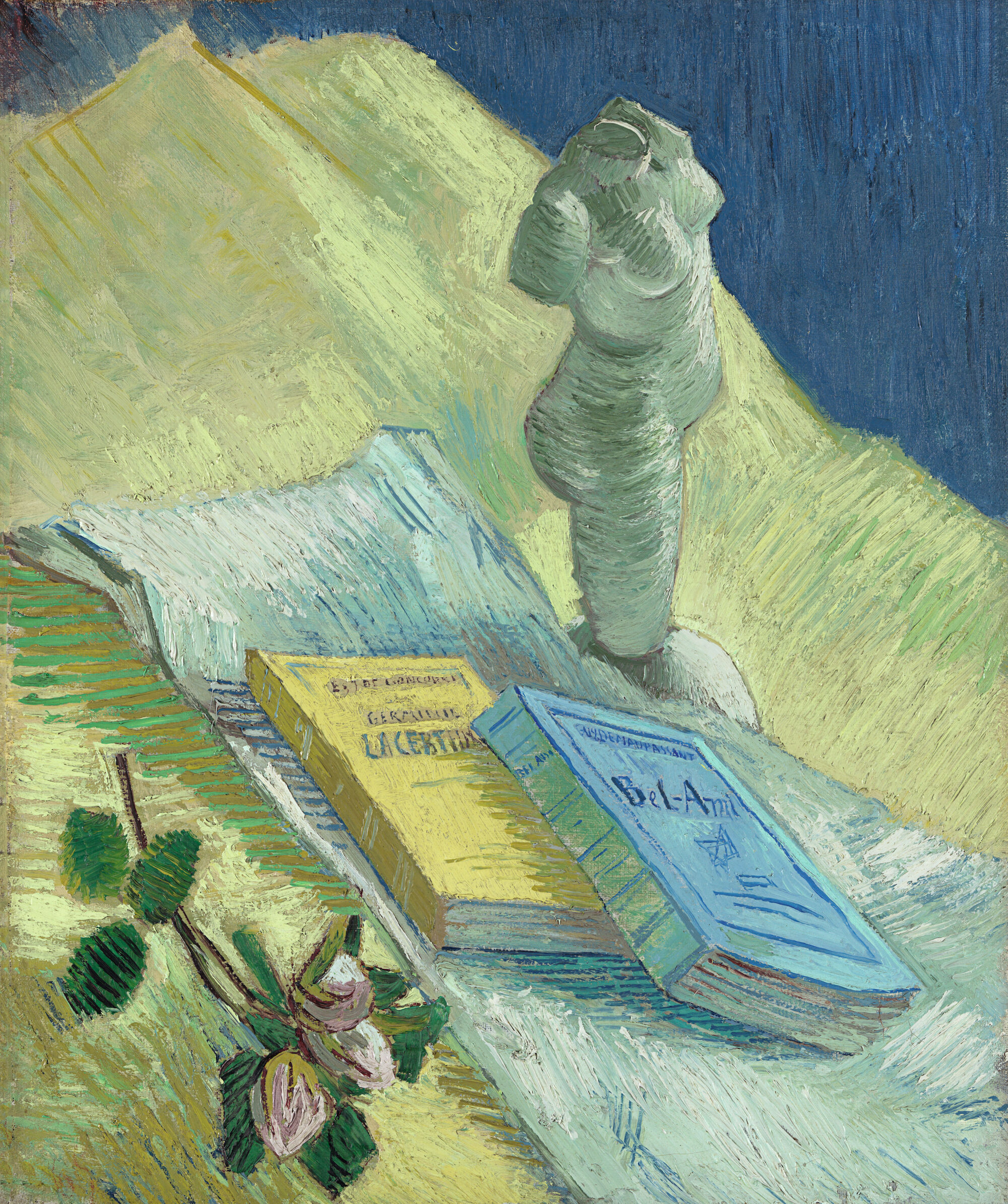

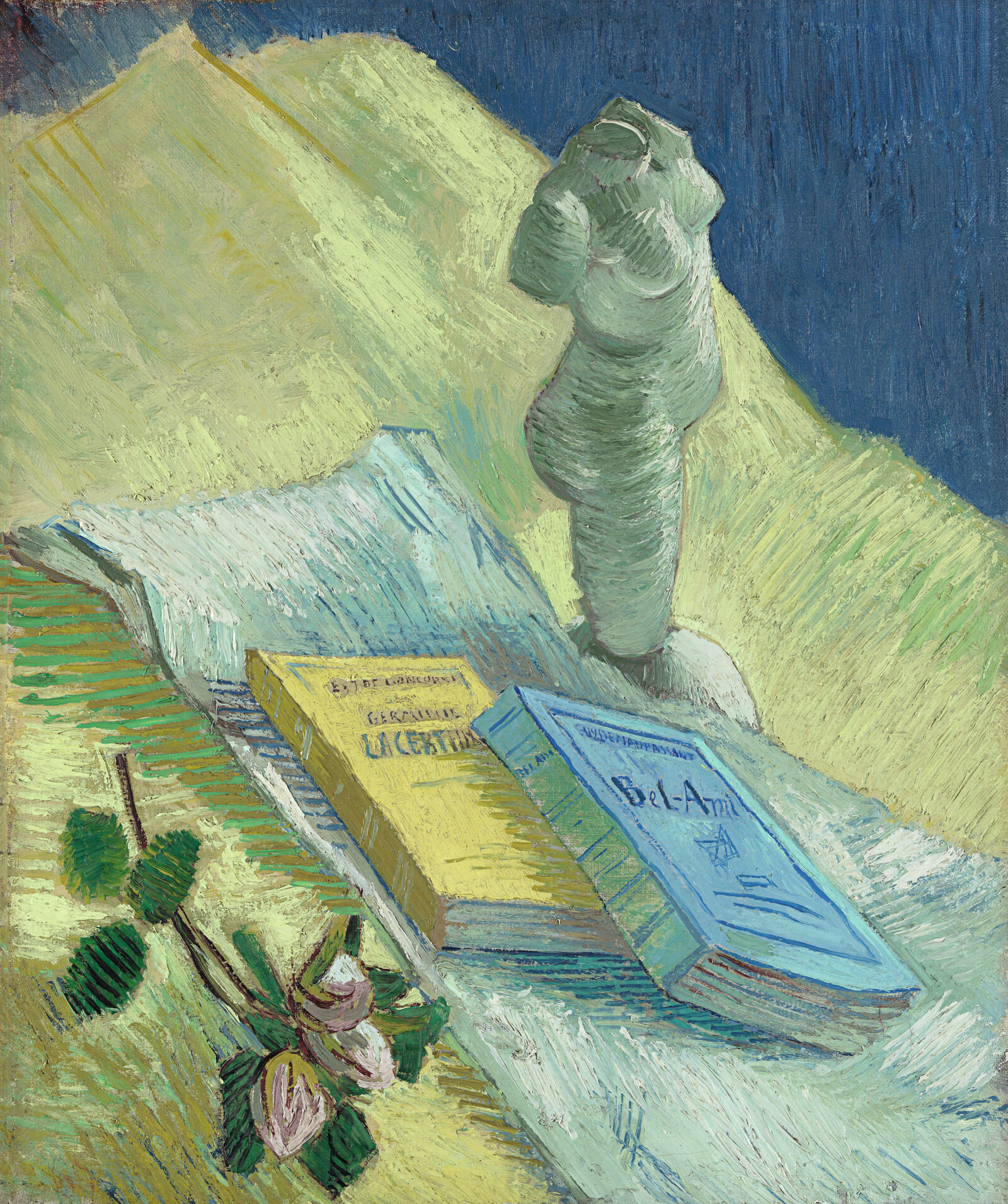

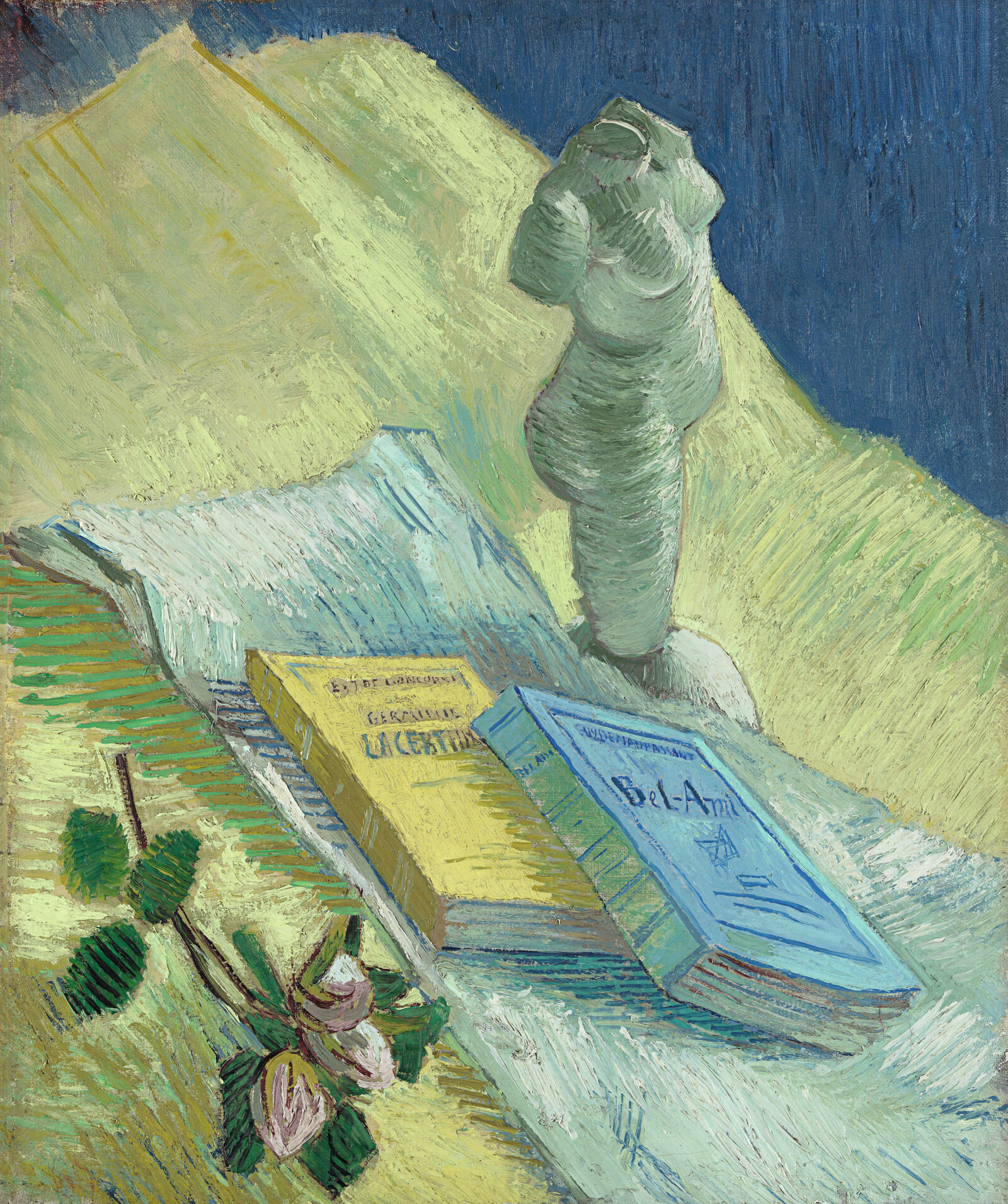

Still Life with Plaster Statuette, 1887, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Apart from Japanese colour woodcuts, works by the impressionists and pointillists were among Van Gogh’s major artistic discoveries in Paris.

Although he felt no allegiance to either of these movements, he drew salient input from their various approaches. By the time his stay in Paris came to an end in 1888, he had forged his own distinctive style: he was shifting away from simply depicting reality and injecting dynamism into the purportedly static genre of still life, as if the painter’s emotions had been absorbed by the objects shown and as if the colours had a life of their own.

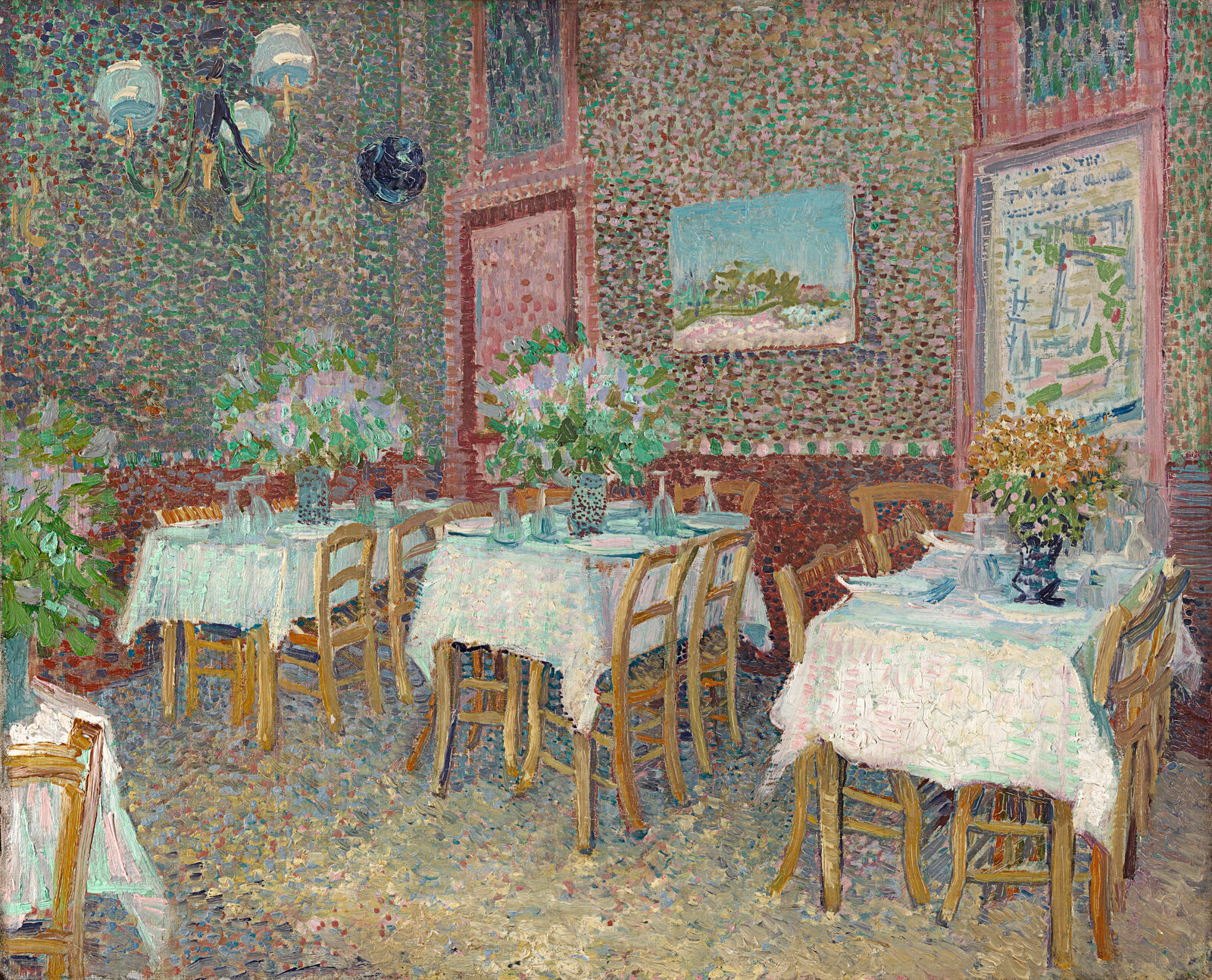

Interior of a Restaurant, 1887, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Carafe and Dish with Citrus Fruit, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

In Paris Van Gogh crossed the threshold into modern art.

He experimented with the dabbing technique of pointillists like Paul Signac, tried applying the paint as thinly as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and borrowed the flatness and perspective of Japanese woodcuts. His visits to the city’s museums also served him as a major source of inspiration. Van Goth catalysed all these influences and experiments into a personal style: dynamic brushwork with strong, parallel strokes of paint, two-dimensional composition and the use of complementary contrasts.

Basket of Lemons and Bottle, 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

In February 1888, after two years in Paris, Van Gogh decided to escape the big city.

In Arles in the South of France he hoped to set up an artists’ community with his friend Paul Gauguin. Fascinated by the Southern light and ebullient vegetation, he worked primarily on landscapes. For many years he had longed to create a painting that consisted entirely of shades of yellow, and he finally achieved this in what is probably his best-known series, the Sunflowers.

In the hope of living in a studio of our own with Gauguin, I’d like to do a decoration for the studio. Nothing but large Sunflowers. [...] Well, if I carry out this plan there’ll be a dozen or so panels. The whole thing will therefore be a symphony in blue and yellow. I work on it all these mornings, from sunrise. Because the flowers wilt quickly and it’s a matter of doing the whole thing in one go.

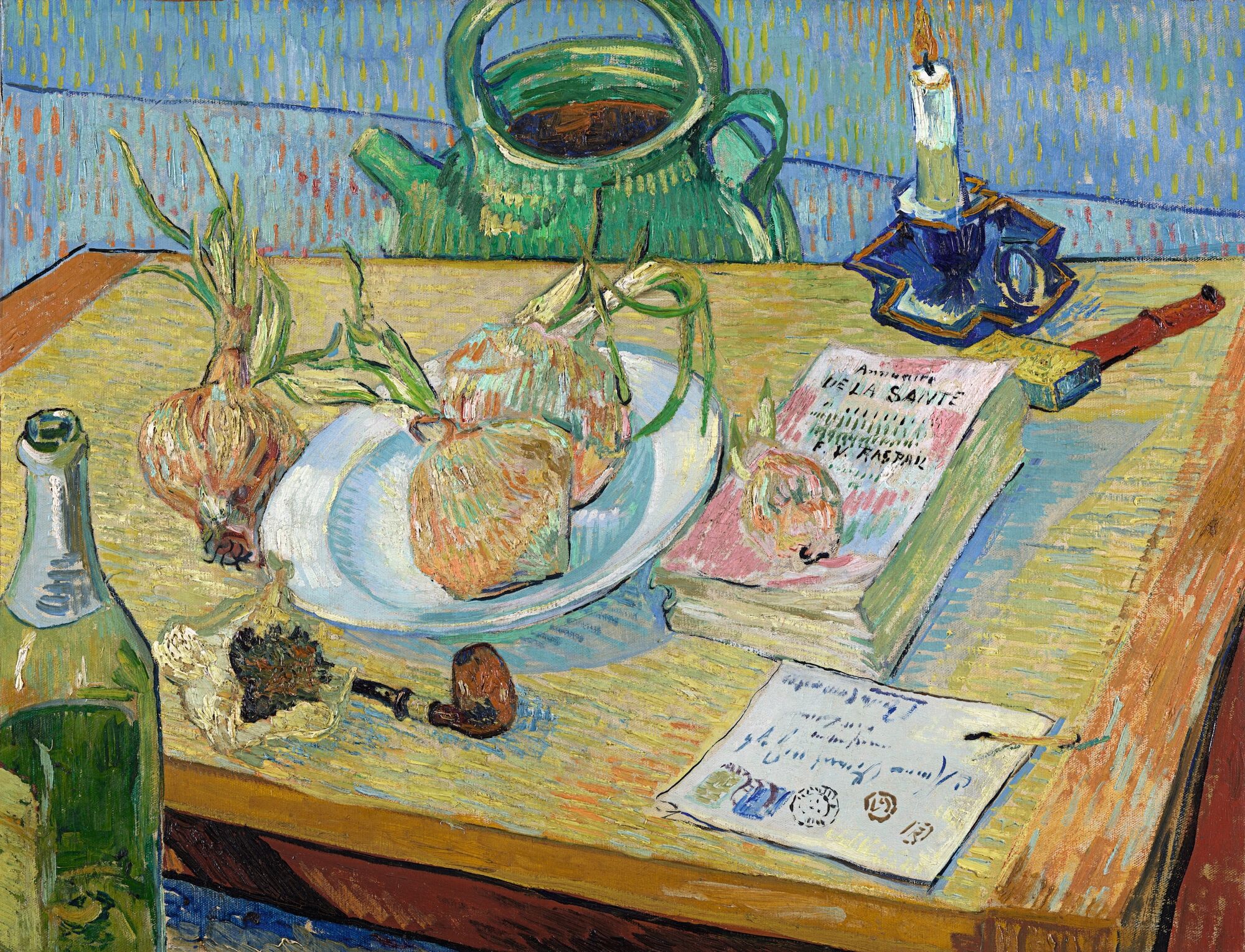

Still Life with a Plate of Onions, 1889, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

In late 1888 the two-month collaboration with Paul Gauguin in Arles came to a dramatic end. During a fierce argument with him, Van Gogh cut off part of his left ear and had to be treated at the local hospital.

In January 1889 he returned to work. His mental state was fragile, however, and a few months later he sought voluntary admission to a psychiatric clinic near Saint-Rémy. There, within the short space of a year, Van Gogh made about 140 paintings, most of them landscapes and very few still lifes.

I’m going to get back to work tomorrow, I’ll begin by doing one or two still lifes to get back into the way of painting.

In Van Gogh’s day, still life were considered to lack passion, serving decorative purposes and consequently unsuited to conveying emotions. Van Gogh’ still lifes, by contrast, often carry a symbolic charge and suggest an existential meaning. The painting Still Life with a Plate of Onions was executed in January 1889, just after his release from hospital in Arles, and it is akin to a self-portrait. The things painted here tell us a lot about Van Gogh’s personal situation.

Still Life with a Plate of Onions, 1889, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

- The tobacco pouch, pipe and empty bottle of absinthe suggest the little pleasures in life to which Van Gogh occasionally treated himself.

- The burning candle stands for Paul Gauguin, whose departure after the argument in December 1888 shattered the dream of an artists’ community after only two months and plunged Van Gogh into a deep mental crisis.

- The letter is a reference to his brother Theo van Gogh and to the importance their correspondence held for the artist.

- The book Annuaire de la santé is a medical journal that Van Gogh had evidently consulted in the hope of improving his physical constitution.

- The onions at the centre of the picture seem to symbolise Van Gogh himself. Onions are associated with tears and a sting of pain, although their green shoots can also signify growth and personal development.

A Pair of Leather Clogs: 1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

After one year in the clinic near Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh moved to Auvers near Paris in the spring of 1890. There the blossoming chestnut trees must have conveyed a sense of great vitality to the artist, who was always receptive to impressions of nature.

In his tireless desire to create, his expressive technique reached its peak. Up until his death on 29 July, he painted almost 80 works in just two months, amongst them ten still lifes.

We [VvG and Dr Paul Gachet] were friends, so to speak, immediately, and I’ll go and spend one or two days a week at his house working in his garden, of which I’ve already painted two studies, one with plants from the south, aloes, cypresses, marigolds, the other with white roses, vines and a figure. Then a bouquet of buttercups. [...] But in the last few days at St-Rémy I worked like a man in a frenzy, especially on bouquets of flowers. Roses and violet Irises.