Surrealism and Magic

With the Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), the French writer André Breton founded a new artistic and literary current. At its center was the world of the dream and the irrational. The exhibition Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity is the first comprehensive show to focus on the Surrealists’ interest in magic and the occult.

Selected masterpieces by world-renowned artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and René Magritte are featured alongside key works by painters that remain to be discovered by the larger museum-going public, amongst them Victor Brauner, Enrico Donati, Jacques Hérold, Wolfgang Paalen, and Kurt Seligmann. In addition, the exhibition highlights the central contribution of women, which comes to the fore in works by artists such as Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Jacqueline Lamba, Kay Sage, Dorothea Tanning, and Remedios Varo.

Numerous artists were familiar with the work of Sigmund Freud, including his influential study Totem and Taboo (1913). There, Freud had defined the basic principle of magic as the belief in the “omnipotence of thought.” The idea of the human imagination as a magical force that can actively influence reality fascinated the Surrealists. Accordingly, they propagated the self-image of the artist as a sorcerer, magician, and alchemist who, thanks to his or her imagination, can conjure up new, illusory worlds.

The prologue to the exhibition explores the Surrealists’ engagement with magic and highlights the extent to which their fantastic iconography was indebted to traditional occult symbolism.

I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak.

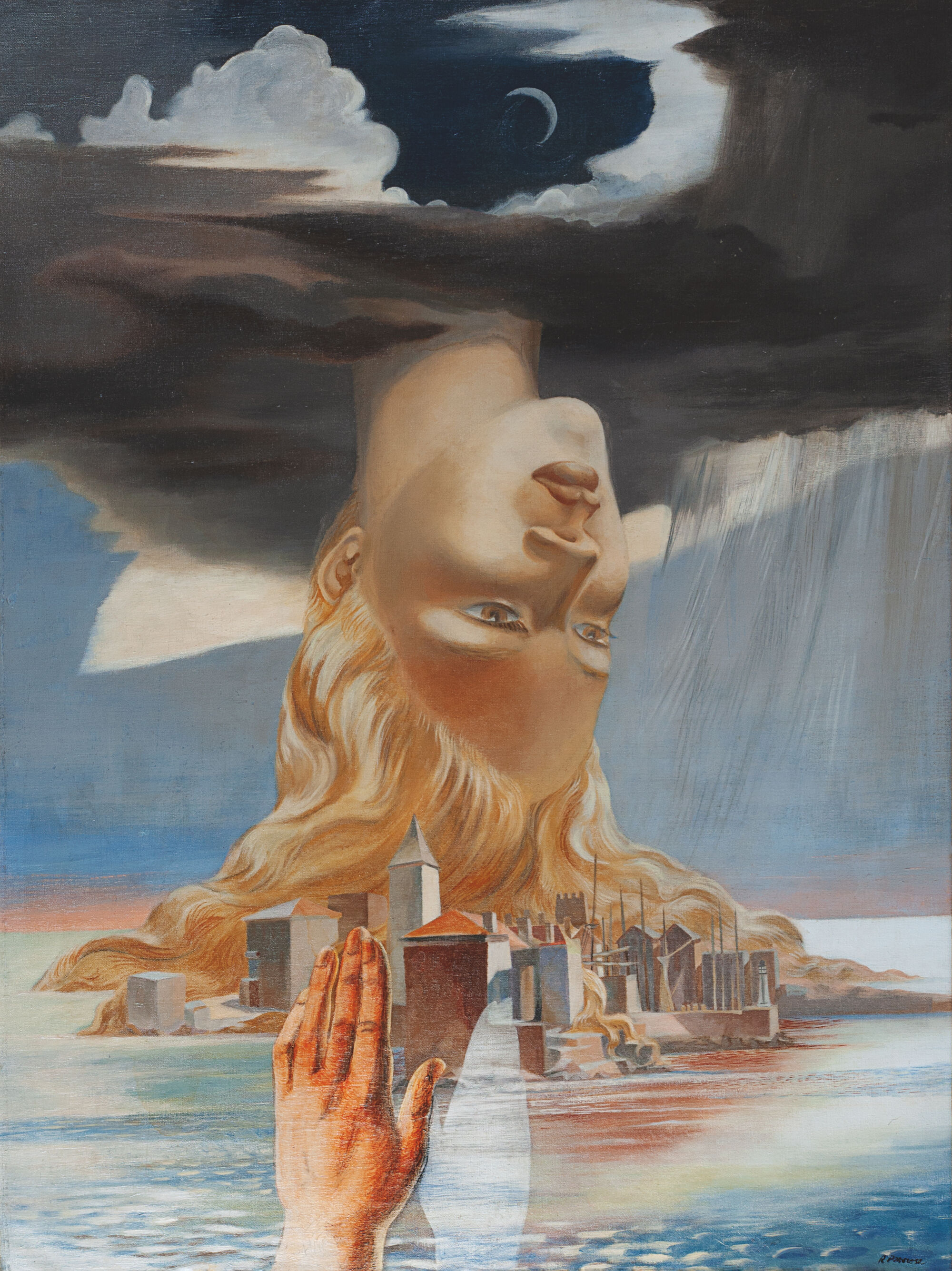

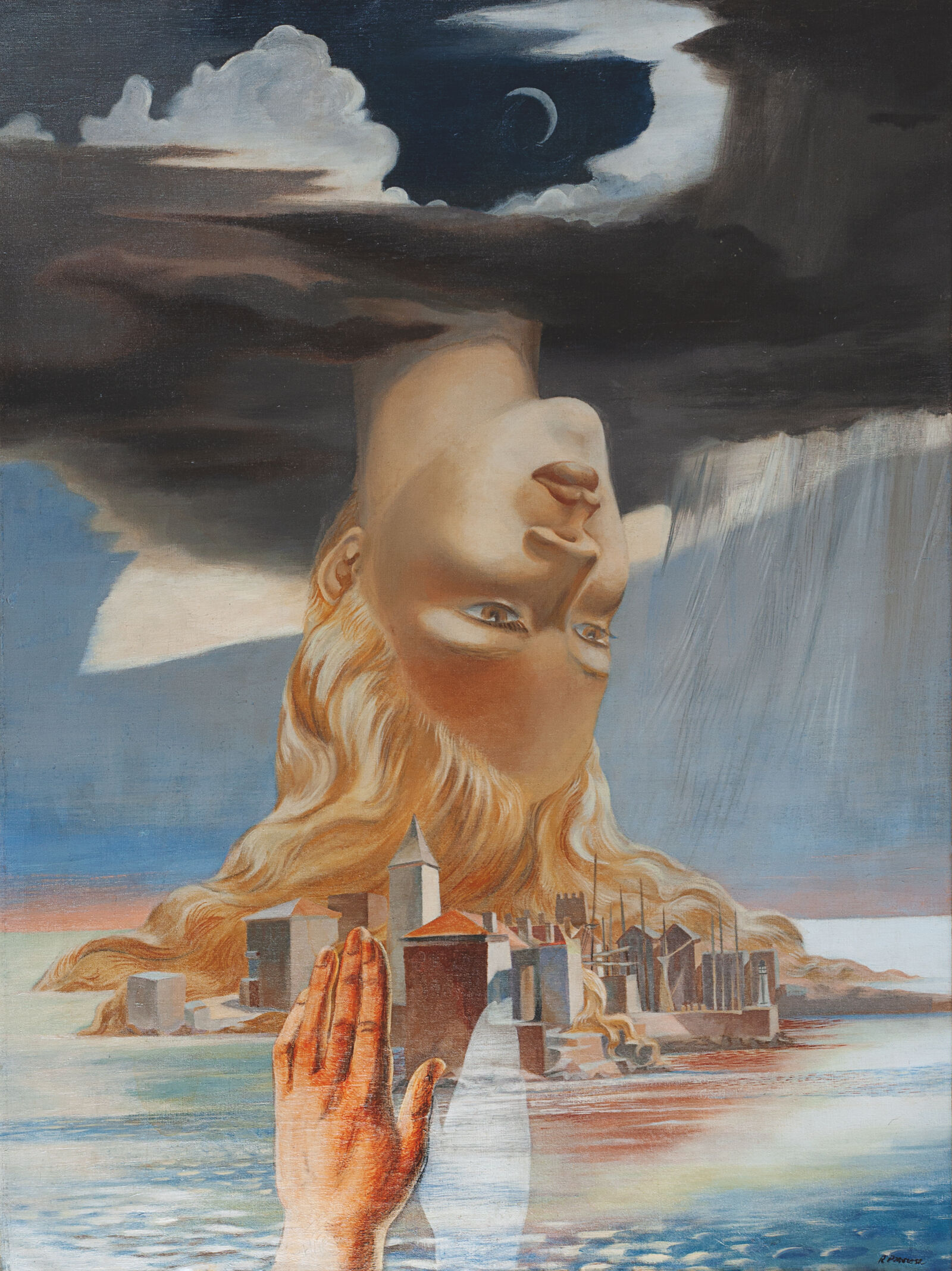

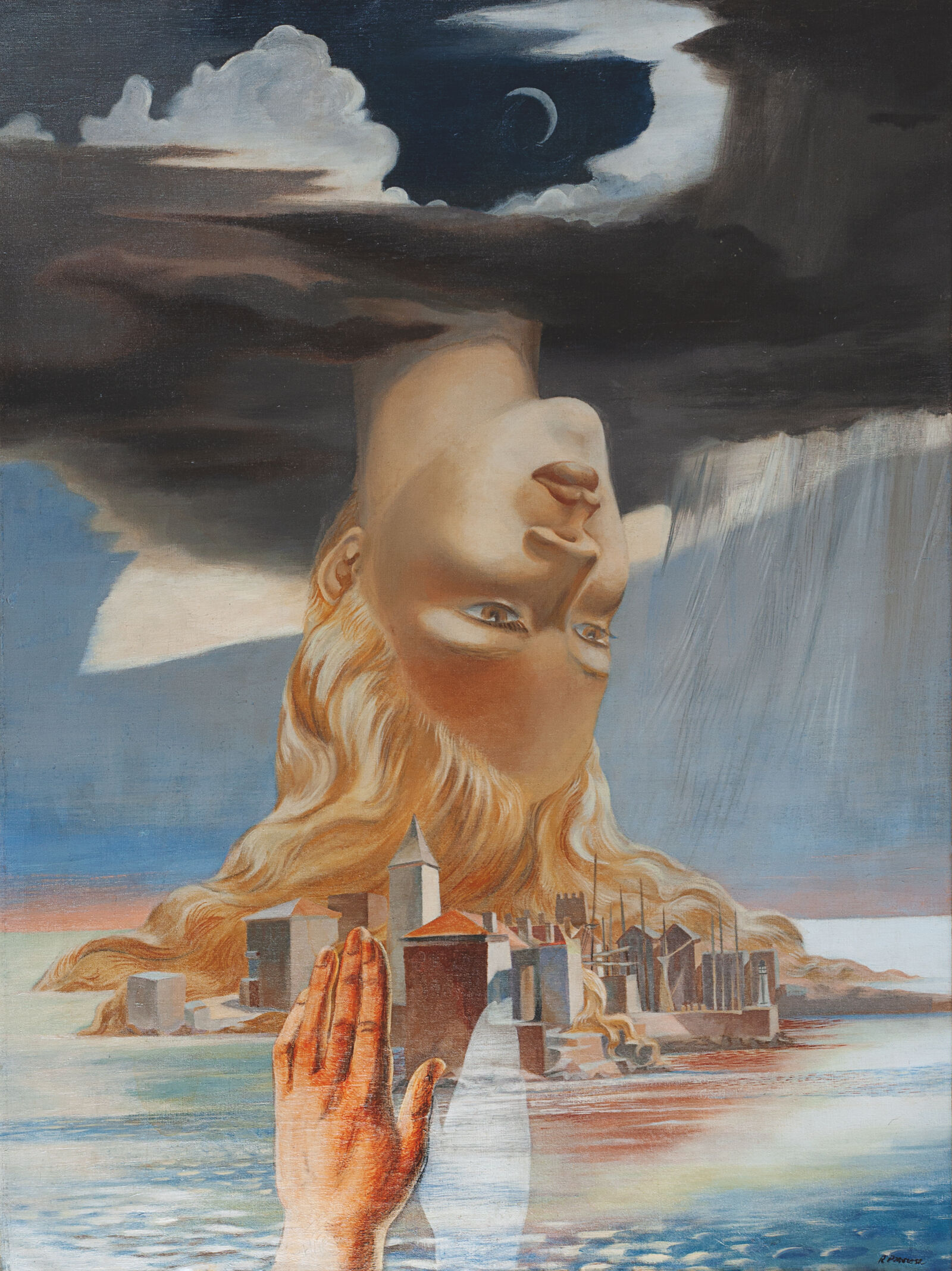

Roland Penrose: Seeing is Believing, 1937, The Penrose Collection

© Lee Miller Archives, England 2022. All rights reserved.

Image: Roland Penrose. Lee Miller Archives, England 2022. All rights reserved. www.leemiller.co.uk

An important precursor of Surrealism was Giorgio de Chirico. With his “Metaphysical Painting “he wanted to give expression to the deep-seated enigma of human existence. Many Surrealists adopted de Chirico’s figurative style. In meticulously executed works, the irrational world of dreams and the unconscious was to take on concrete form. Numerous works depict human protagonists who become participants in magical rituals. In addition, themes of transformation and metamorphosis as well as the regenerative forces of nature also play a significant role.

Giorgio de Chirico: The Child's Brain, 1914, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Moderna Museet, Stockholm

In de Chirico’s painting The Child’s Brain, the closed eyes of the naked man not only symbolize the world of dreams and fantasy, but also introspection and clairvoyance.

Magic was a stimulus to thinking. It freed man from fears, endowed him with a feeling of his power to control the world, sharpened his capacity to imagine, and kept awake his dreams of higher achievement.

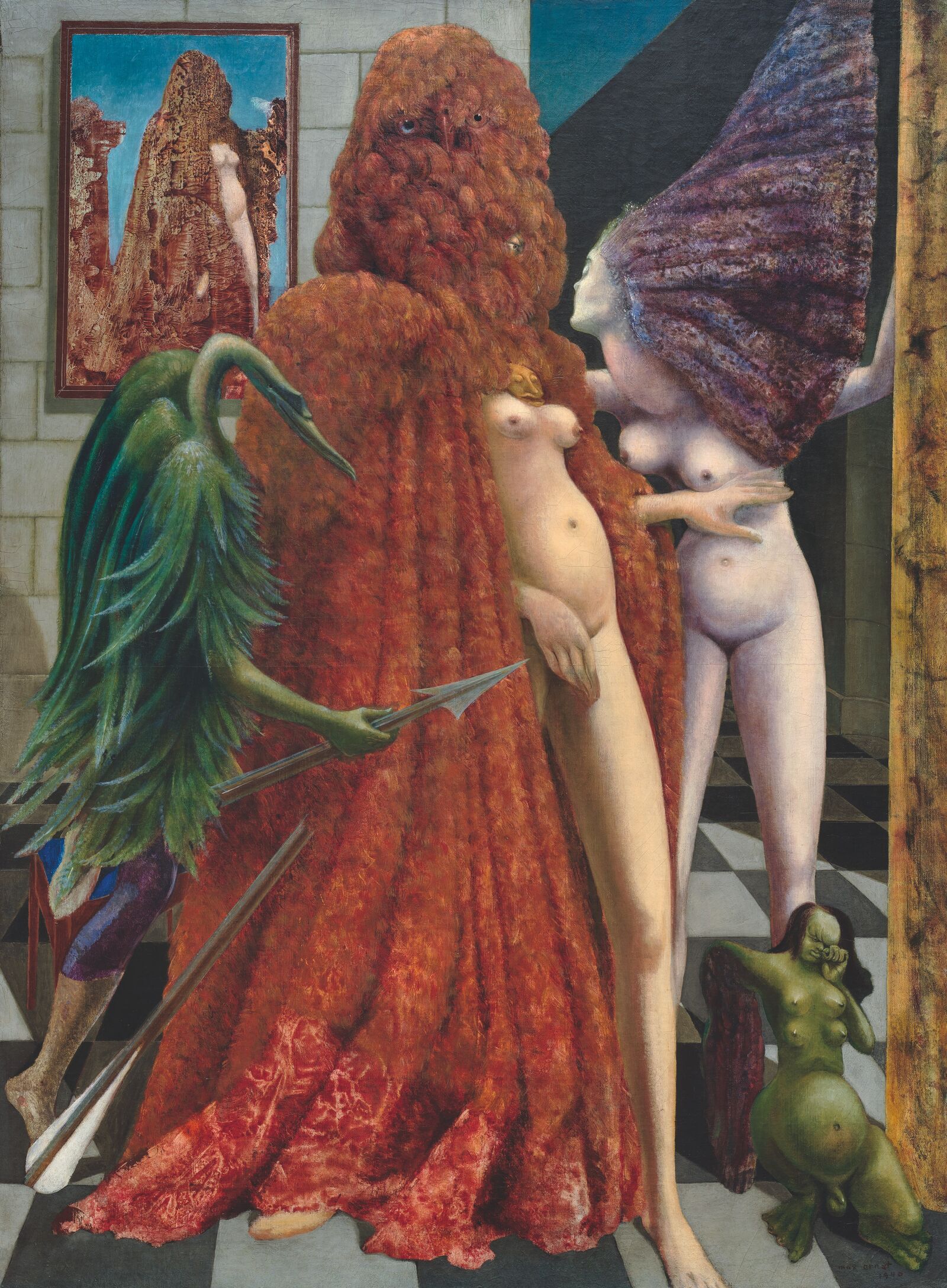

Max Ernst: Attirement of the Bride, 1940, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York)

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, Photo: David Heald

Max Ernst produced his magisterial work Attirement of the Bride as a tribute to his partner, the English Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington. He drew inspiration from traditional Renaissance depictions of witchcraft. As in a magical ritual, the naked seductress is being robed in a majestic feather cloak. As the core signifying color of magic, the luminous red associates its wearer with great magical power.

André Masson was a Surrealist of the first hour. In the 1930s, he produced several works in which the female body is associated with magical renewal. His painting Ophelia references the eponymous heroine of Shakespeare’s drama Hamlet.

Ophelia, a young noblewoman in love with the title character of William Shakespeare’s drama Hamlet, drowns in a state of madness at the end of the play. André Masson combines the motif of her death with allusions to rebirth: Ophelia’s eyes are cast in the shape of blooming flowers, while the dragonfly playing the flute on the right symbolizes metamorphosis and transformation.

André Masson: Ophelia, 1937, The Baltimore Museum of Art

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: The Baltimore Museum of Art, Photo: Mitro Hood

The painting reflects Masson’s fascination with the mythical notion of powerful mother goddesses presiding over the eternal cycle of life and death. His Ophelia is the emblematic embodiment of such magical, feminine agency. The choice of green as the dominant hue is significant, too: it symbolizes the regenerative forces of nature as well as the power of rebirth.

In its early stages, Surrealism was an exclusively male movement. It was not until the 1930s that it increasingly drew female artists into its fold, amongst them Leonora Carrington. The English-born painter executed this depiction of a red glowing witches’ kitchen as a tribute to her Irish grandmother, who had introduced her to the magical world of Celtic mythology when she was still a young girl.

Leonora Carrington: Grandmother Moorhead's Aromatic Kitchen, 1975, The Charles B. Goddard Center for the Visual and Performing Arts, Ardmore, Oklahoma, USA

© VG Bild-Kunst, 2022

Image: Cory D. Blankenship

Carrington associated the preparation of food with magical rites. Fittingly, the circular stone table here recalls a pagan altar. It is surrounded by a protective spell circle that Carrington has inscribed with magical signs. The white goose likely figures as a symbolic companion of the magically powerful “White Goddess” of Celtic mythology.

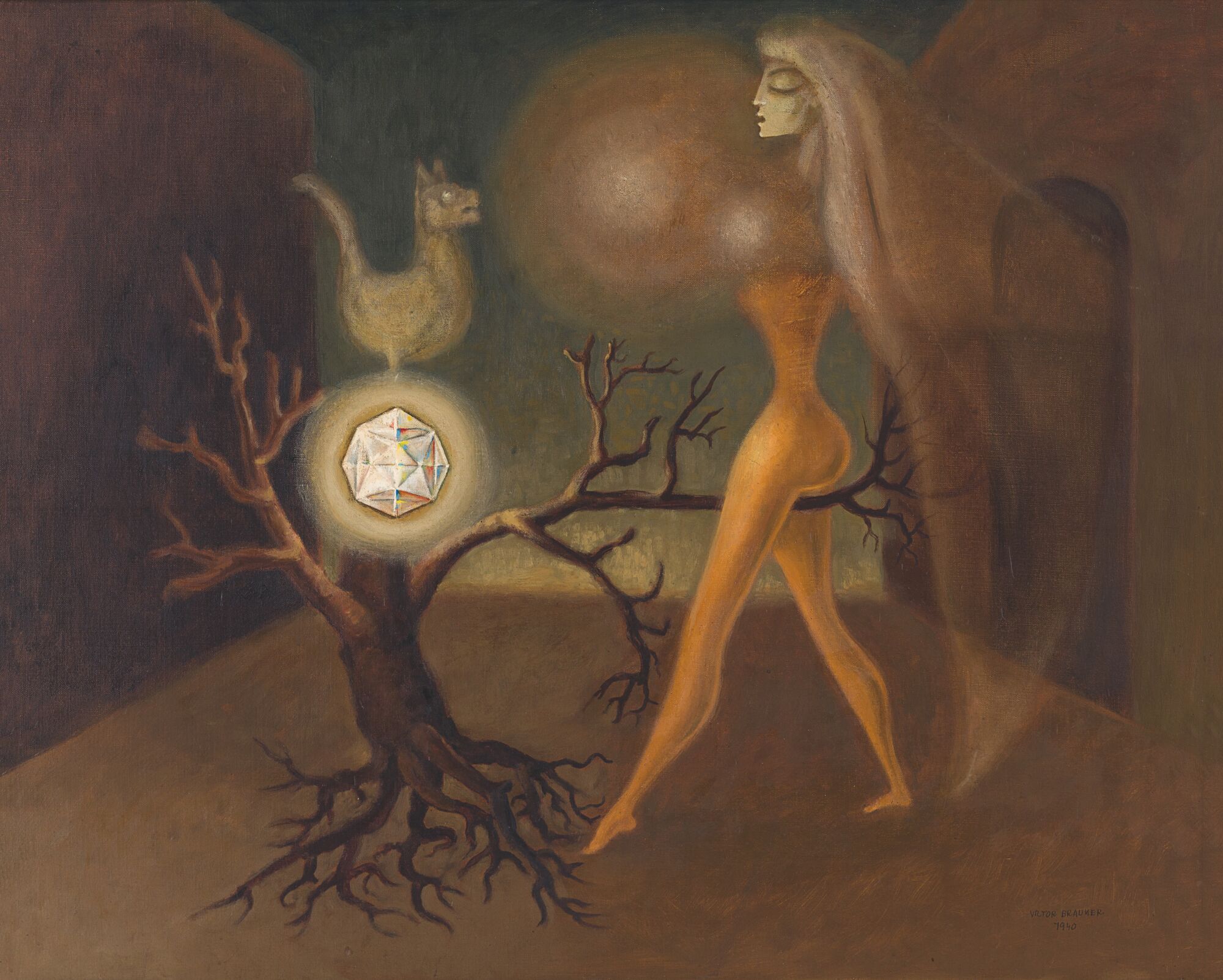

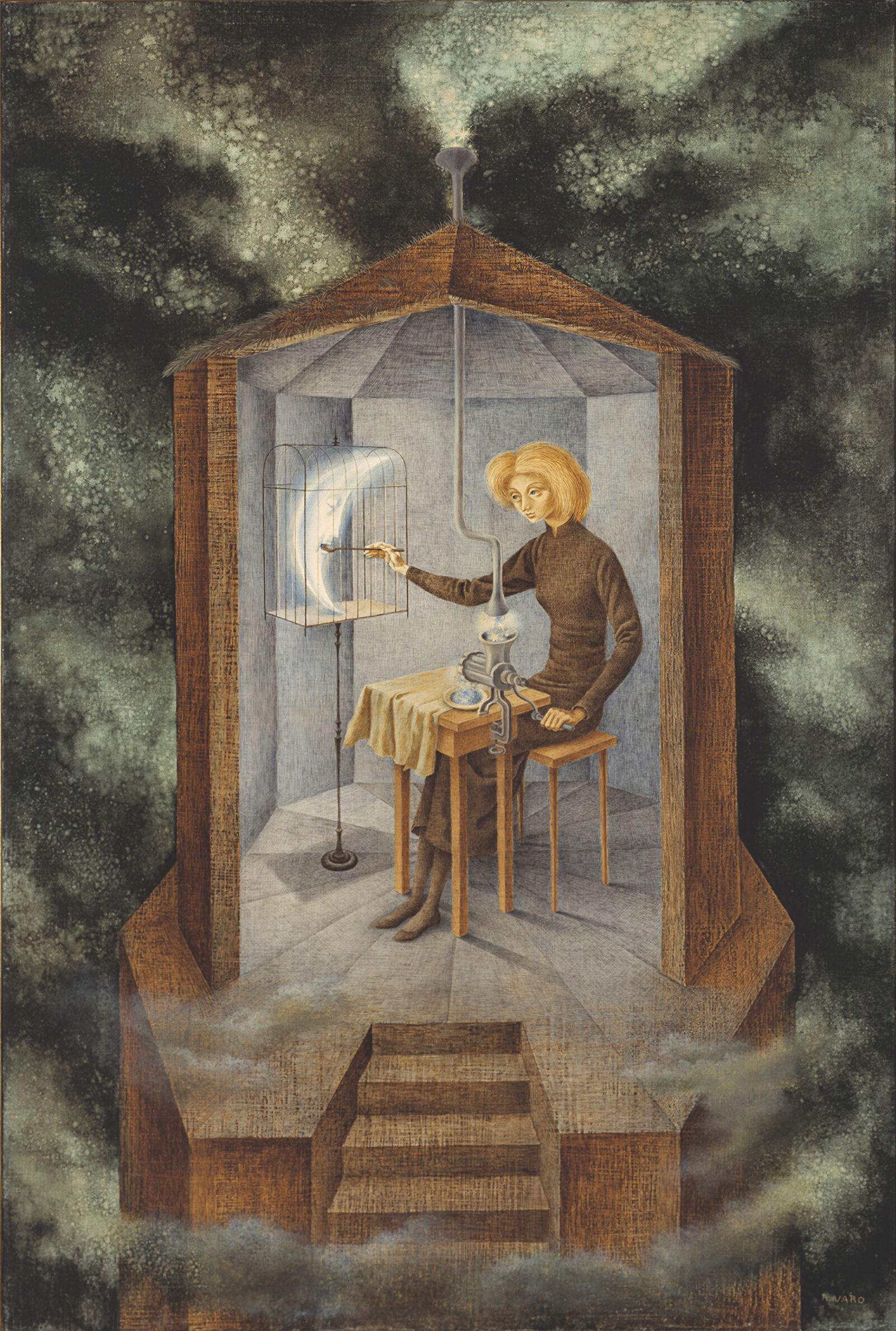

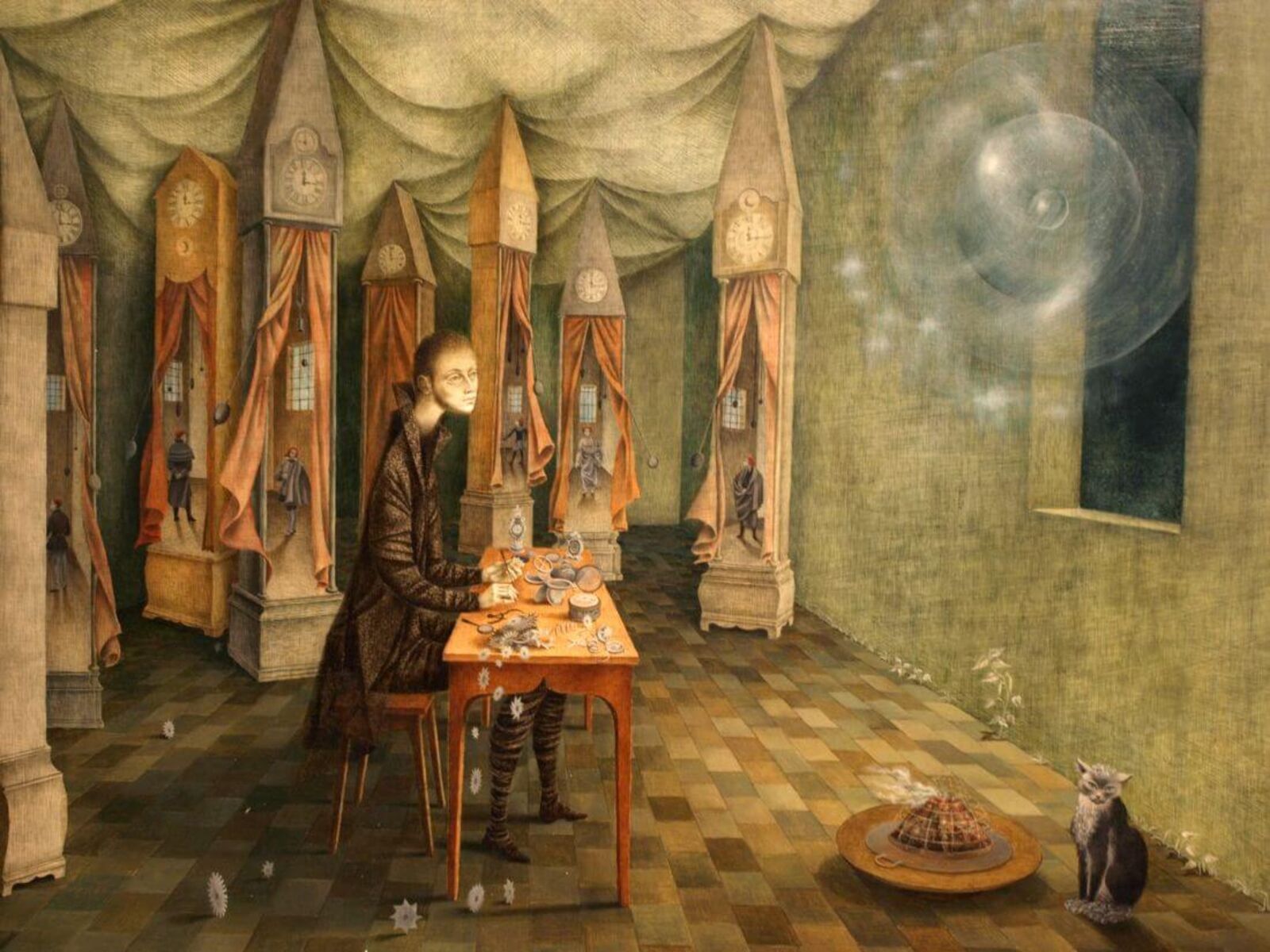

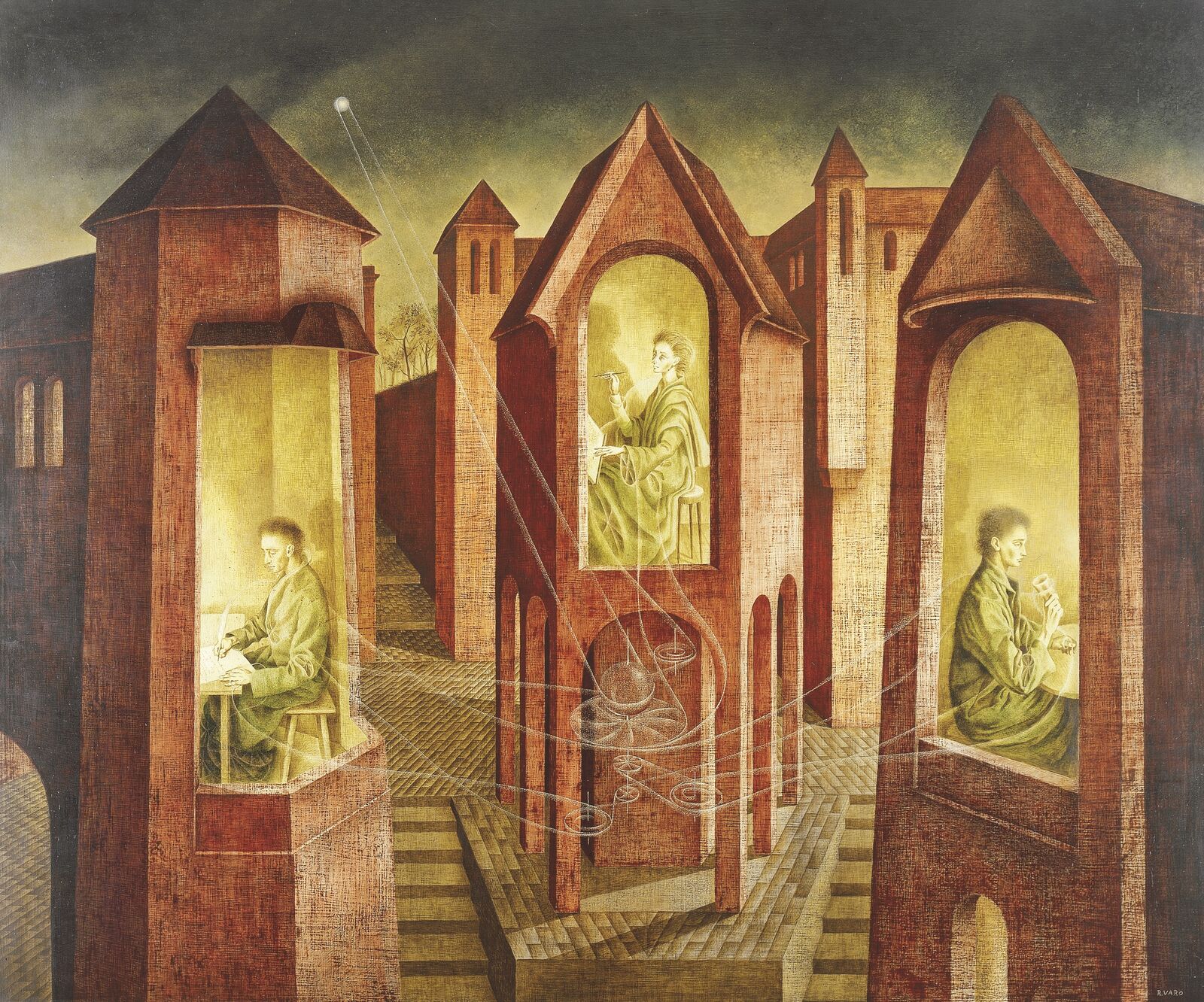

Like Leonora Carrington, the Spanish artist Remedios Varo also found a connection to Surrealism in the 1930s. Many of her works combine magical scenarios with allusions to science and technology. Varo’s constant recourse to fantastic machines was directly related to her keen childhood memories of the detailed drawings of her father, who had worked as a hydraulics engineer.

A young blonde woman grinds star matter into a celestial pablum. With this magical nourishment the cosmic nurse nurtures a sickly crescent moon.

Varo’s paintings are captivating for their fine painterly execution. Her clockmaker is both a scientist and a magician. The cat in the lower right is probably his magical companion animal.

Victor Brauner: The Philosophers' Stone, 1940, Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Saint-Etienne Métropole

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Photo: Cyrille Cauvert

Many Surrealists looked to the symbolism of alchemy – an ancient science centered on processes of material transformation. In alchemy, the fusion of the elements and the concommitant production of the Philosophers’ Stone is symbolized by the “Royal Wedding”: the sexual fusion of man and woman, fire and water, golden sun and silver moon, red king and white queen – for the Surrealists, a symbolic expression of the omnipotence of desire.

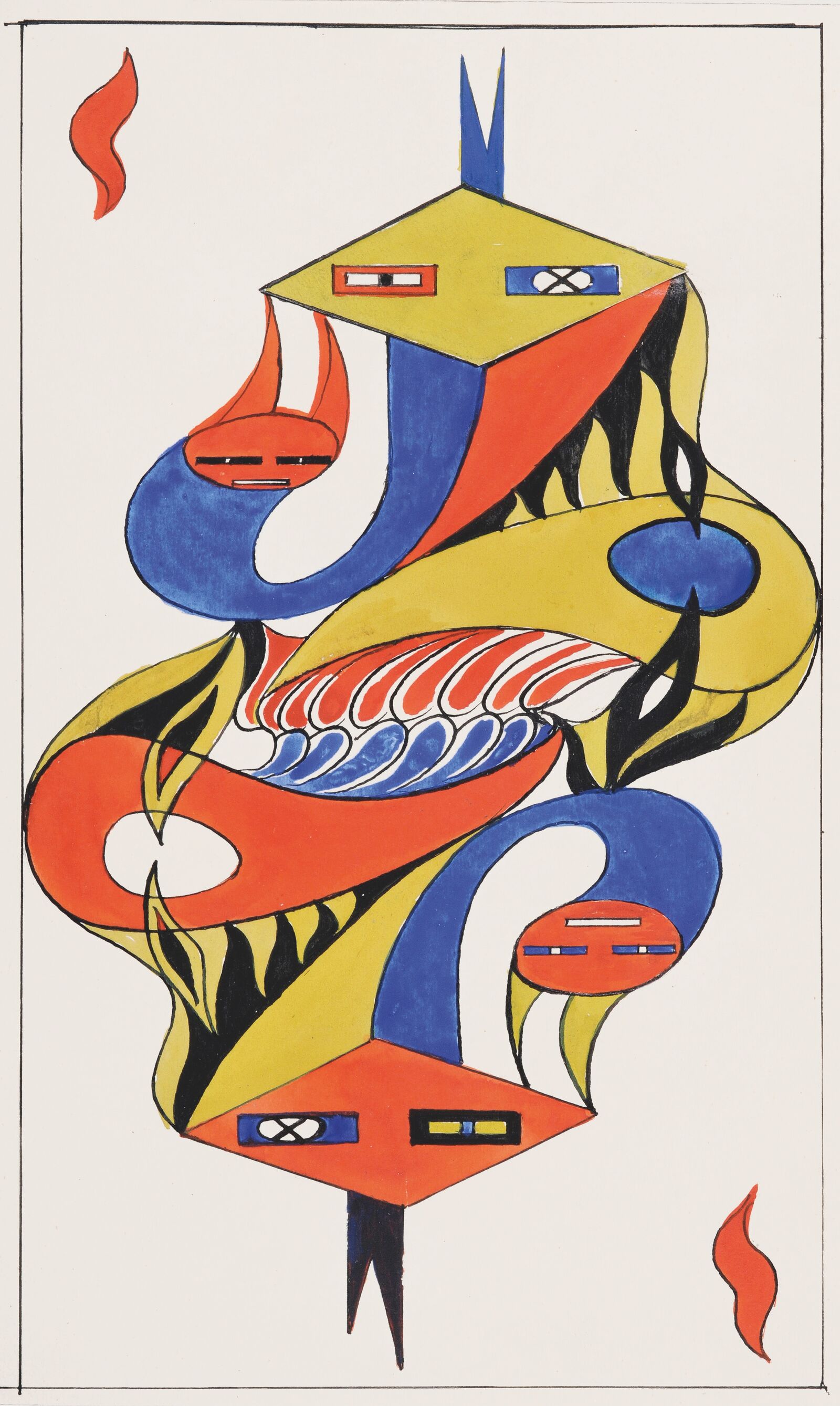

Victor Brauner: The Surrealist, 1947, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Photo: David Heald

Victor Brauner’s The Surrealist builds on the iconography of the tarot – a deck of cards that has been used for divinatory purposes since the 18th century. As a template he took the card “The Magician,” which symbolizes willpower and creativity. The four attributes of the figure (wand, coins, chalice and dagger) represent the alchemical power over the four elements and indicate that the magician is in possession of the elixir of life and thus also of immortality.

In his painting The Lovers, Victor Brauner combined the iconography of two different tarot cards: “The Magician” and “The Priestess.” The meeting of the magically powerful figures is supposed to symbolize the wedding of the alchemical royal couple. This is also referred to by the scepter of the magician, which combines the attributes of golden sun and silver moon.

Victor Brauner: The Lovers, 1947, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: © bpk, Berlin: CNAC-MNAM / Photo: Philippe Migeat

Brauner’s painting The Lovers was dedicated to André Breton and was a centerpiece of the International Surrealism Exhibition held in Paris in 1947. The show was entirely focused on themes of myth, magic, and alchemical regeneration.

Max Ernst, who had emigrated to New York, met the US-American artist Dorothea Tanning in the early 1940s. Their shared interest in alchemy and the occult underpinned the artist couple’s motivic dialogue. Both Ernst and Tanning were avid chess players and associated the figures of king and queen with the traditional iconography of alchemy.

Max Ernst: Der König, der mit der Königin spielt, 1944, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Photo: Avshalom Avital

Ernst’s 1944 sculpture The King Playing with the Queen can be read as a symbolic self-portrait in which Max Ernst “plays” with Dorothea Tanning as his alchemical queen. The motif also has erotic and sexual connotations.

Leonora Carrington also devoted herself to the motif of the “Royal Wedding”. Like Brauner’s Surrealist, Carrington’s Necromancer is based on the iconography of the tarot card “The Magician.” With black, white, and red, the three symbolic colors of alchemical transformation dominate the picture. In the necromancer’s clothes, black and white also signify the fusion of opposites such as above and below, male and female, day and night – and thus the “Royal Wedding.”

Leonora Carrington, The Necromancer, ca. 1950, Private collection, courtesy Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco (Photos: Nicholas Pishvanov und Carter Andereck)

Leonora Carrington’s sorcerer, a necromancer, wants to bring to life the animal that is enclosed in a glass vessel to the right. The blue eggs symbolize rebirth and rejuvenation, the luminous butterflies transformation and metamorphosis.

People speak with justice of the ‘magic of art’ and compare artists to magicians (…). There can be no doubt that art did not begin as art for art’s sake. It worked originally in the service of impulses which are for the most part extinct to-day. And among them we may suspect the presence of many magical purposes.

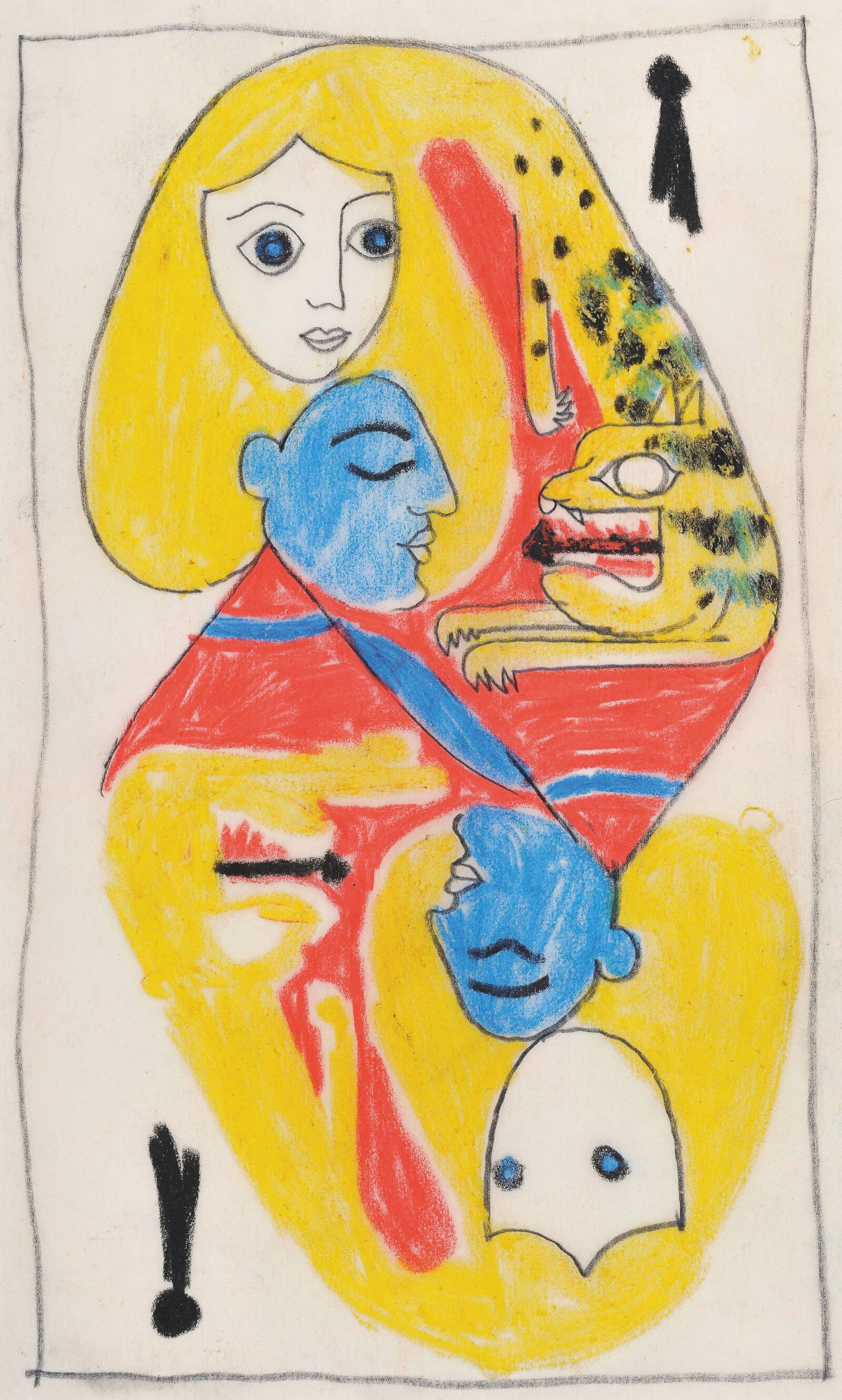

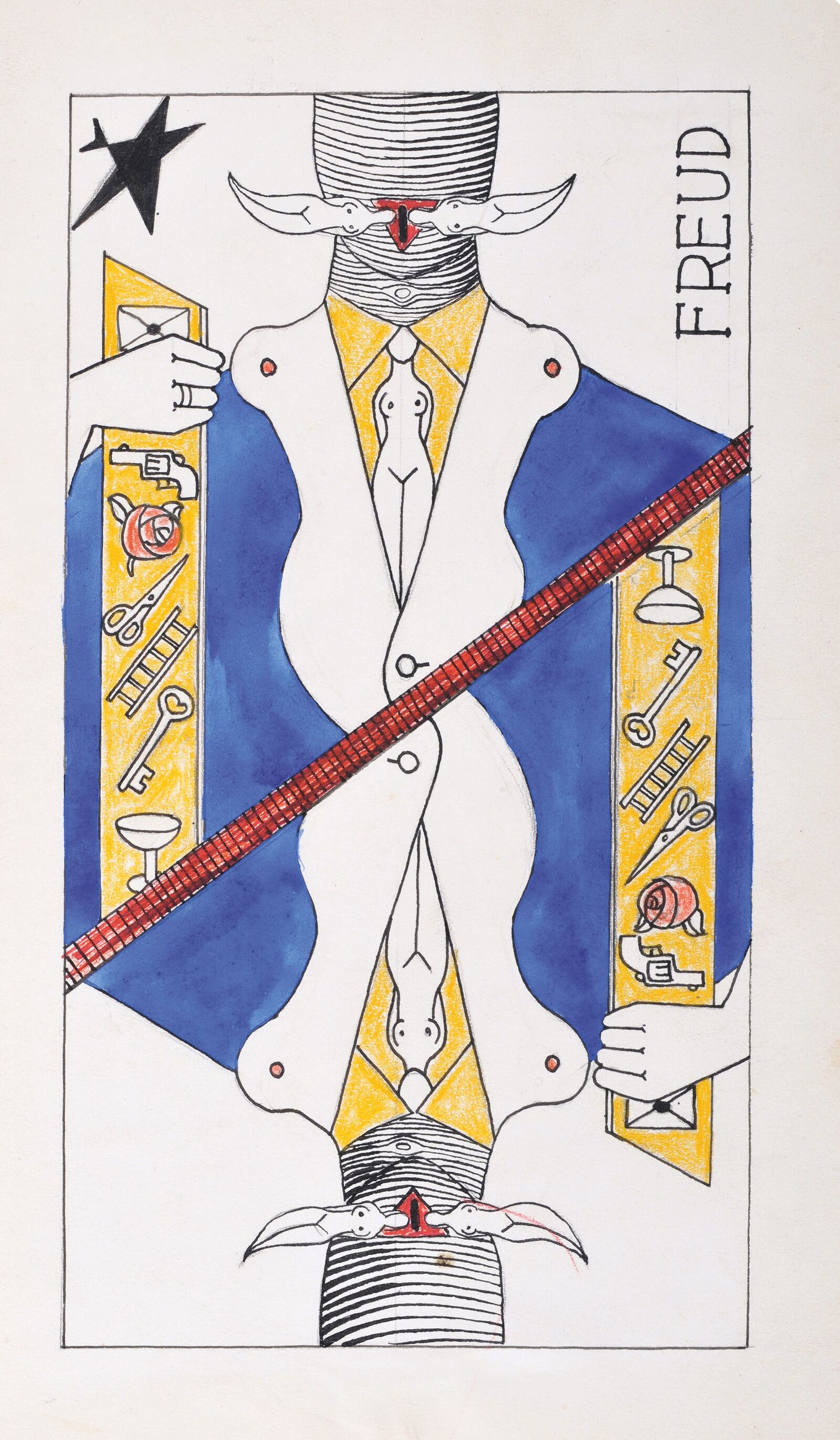

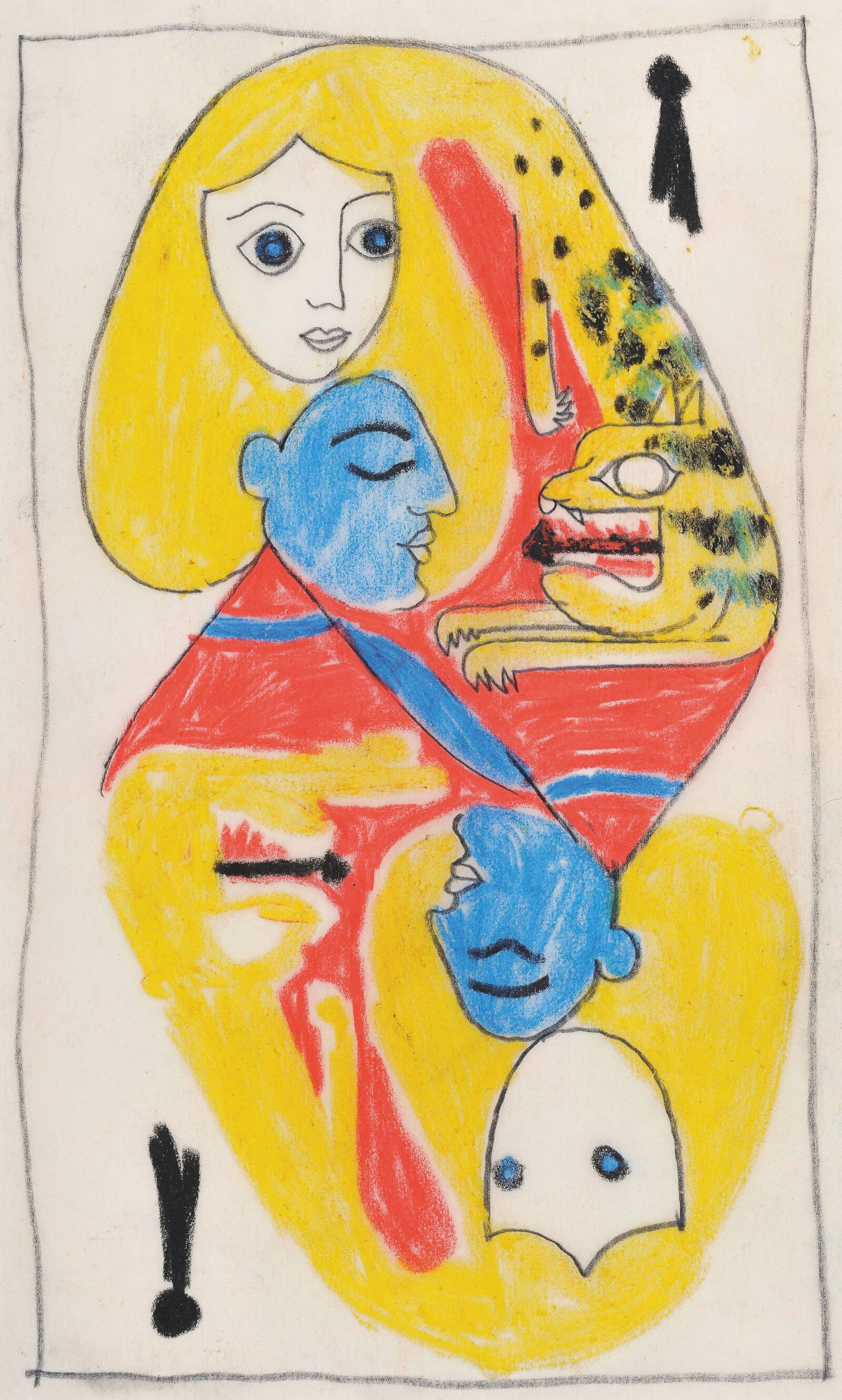

During an extended stay in Marseille in 1941, eight artists produced a new variation of the tarot: a surrealist deck of cards that brims with occult and alchemical symbolism. The four suits (star, flame, keyhole, and bloody wheel) symbolize dream, love, knowledge, and revolution. The trump cards do not show the traditional figures of king, queen and jack, but the occult symbols of magus, siren and genius.

Jacqueline Lamba: Ace of Revolution—Wheel, 1941, Musée Cantini, Marseille

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Abbildung: RMN-Grand Palais / Photo: Jean Bernard

Jacqueline Lamba, André Breton’s partner, was the only woman involved in the production of the Jeu de Marseille. The artists were free to choose the materials and the motifs of the individual cards. In the traditional tarot, the wheel stands for Fortuna, the goddess of fate. Here, it acts as a symbol of revolutionary renewal.

Óscar Domínguez: Freud, Magus of Dreams, Star, 1941, Musée Cantini, Marseille

© VG Bild-Kunst, 2022

Image: RMN-Grand Palais / Photo: Jean Bernard

The writings of Sigmund Freud were an important source of inspiration for Surrealism. Óscar Domínguez celebrated the psychoanalyst as the “magus of dream.” The rose and the pistol represent Eros and Thanatos, the love instinct and the death drive. The depiction of Freud’s body and his clothing contains numerous allusions to sexuality and desire.

Victor Brauner: Hélène Smith, Siren of Knowledge—Locks, 1941, Musée Cantini, Marseille

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: RMN-Grand Palais / Photo: Jean Bernard

In the 19th century, séances came into vogue: spiritualistic sessions in which so-called mediums supposedly entered into contact with the spirit world. Victor Brauner chose one of the most famous of these mediums, the Swiss Hélène Smith, as the embodiment of his “Siren of Knowledge.”

Jacqueline Lamba: Baudelaire, Genius of Love — Flame, 1941, Musée Cantini, Marseille

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: RMN-Grand Palais / Photo: Jean Bernard

The Surrealists were fascinated by 19th-century Symbolist poetry. The choice of Charles Baudelaire as the “Genius of Love” was probably influenced by the writings of André Breton. In his Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), he had hailed the French poet as a precursor of Surrealist literature.

Leonora Carrington: Night of the 8th, 1987, The Penrose Collection

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: courtesy Lee Miller Archives, England 2022. All rights reserved. www.leemiller.co.uk

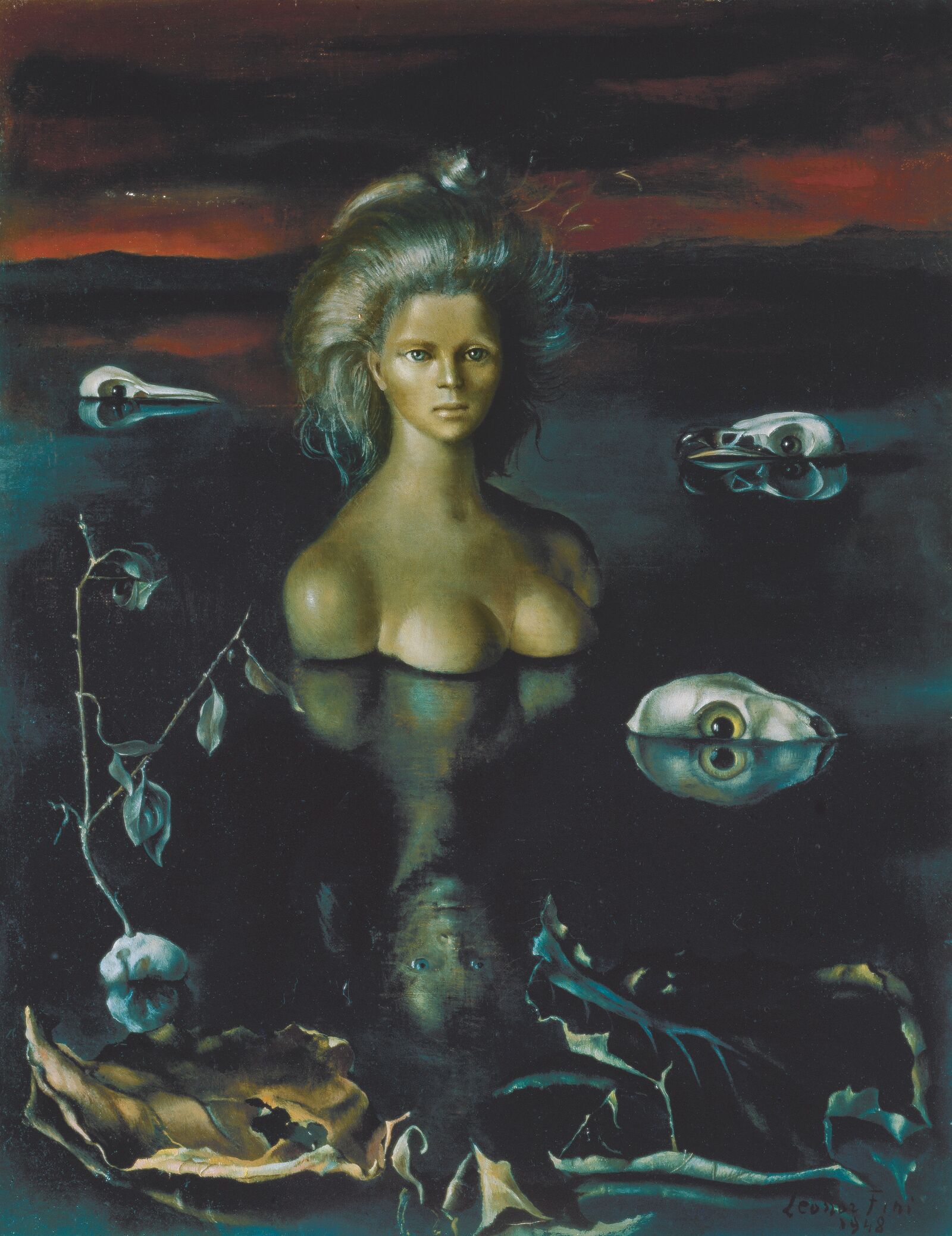

The Surrealists were fascinated by the notion of woman as an irrational and magical being, who is mysteriously connected to the creative forces of nature. Their positive association with the world of the dream and the unconscious was accompanied by cliché-laden stereotyping. Often, the female body is displayed as an erotic object. Female artists such as Leonor Fini and Dorothea Tanning critically countered the images of women produced by their male colleagues.

Paul Delvaux: The Break of the Day, 1937, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York)

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, Photo: David Heald

The female figures in Paul Delvaux’s Break of Day are hybrid beings: half tree trunk, half human. Their anchoring in the ground points to their magical connection to the realm of nature. Delvaux depicts the group as a round dance gathered around an altar-like object. The iconography is a nod to Albrecht Dürer’s 1497 engraving The Four Witches.

René Magritte: Black Magic, 1945, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: J. Geleyns

In René Magritte’s painting Black Magic, the nude woman’s body changes color from a realistic skin tone to a luminous blue. In this way, Magritte refers to her symbolic connection with the sky and the sea. The idealized figure is reminiscent of ancient statues of Venus, the goddess of love.

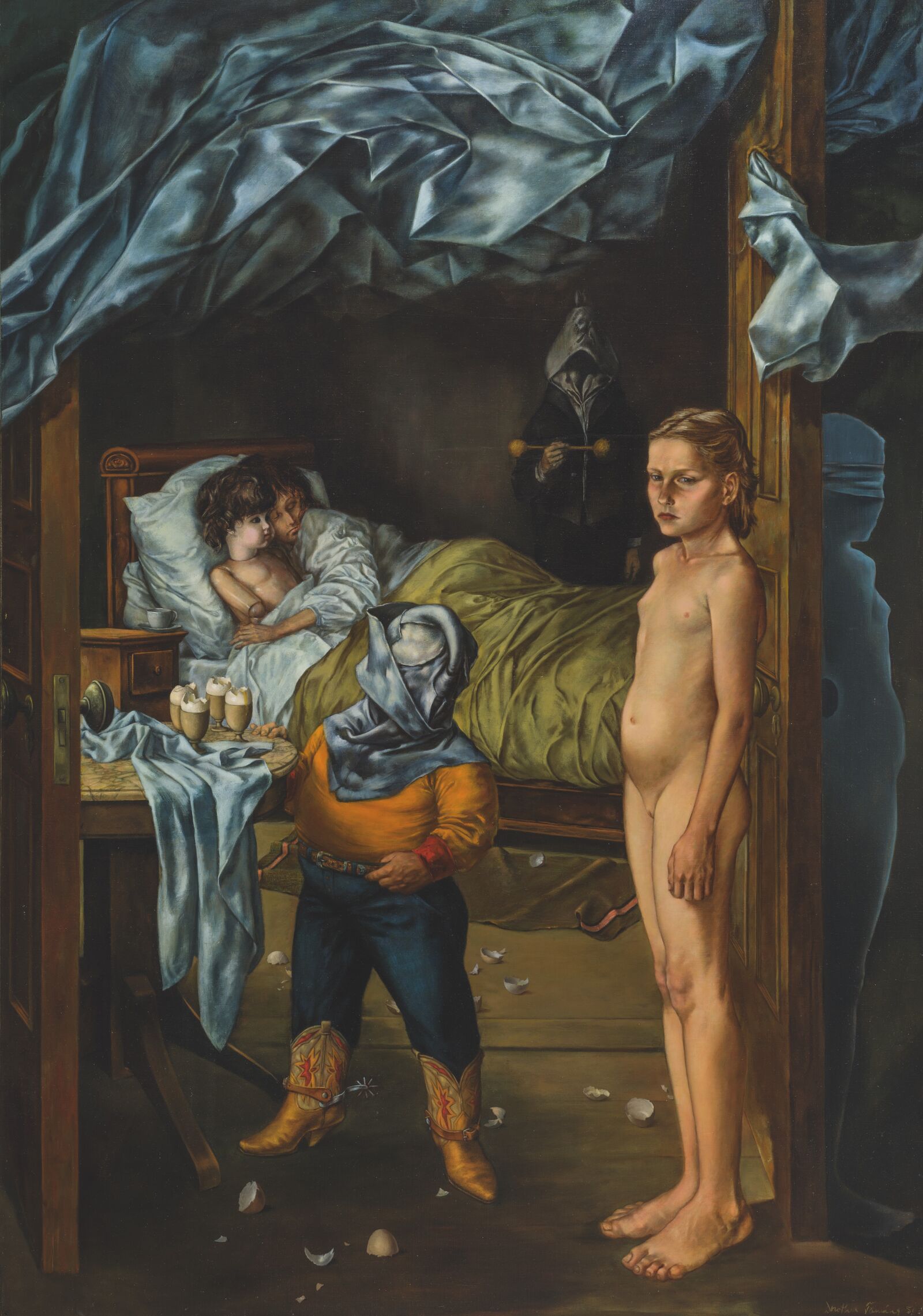

In 1936, the New York Museum of Modern Art organized the exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, which was key to the spread of Surrealism throughout the United States. Dorothea Tanning was among the many American artists to join the movement. Her painting The Guest Room shows a nocturnal nursery in which two ghosts are haunting. The open door symbolized the entrance into the realm of dream and fantasy.

I wanted to lead the eye into spaces that hid, revealed, transformed all at once and where there would be some never-before-seen image, as it if happened with no help from me.

Dorothea Tanning: The Guest Room, 1950-52, Private collection, Courtesy Malingue S.A.

© The Estate of Dorothea Tanning / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Courtesy Malingue S.A., Photo: Florent Chevrot

The eerie atmosphere in Dorothea Tanning’s The Guest Room reminds us of her fascination with Gothic literature.

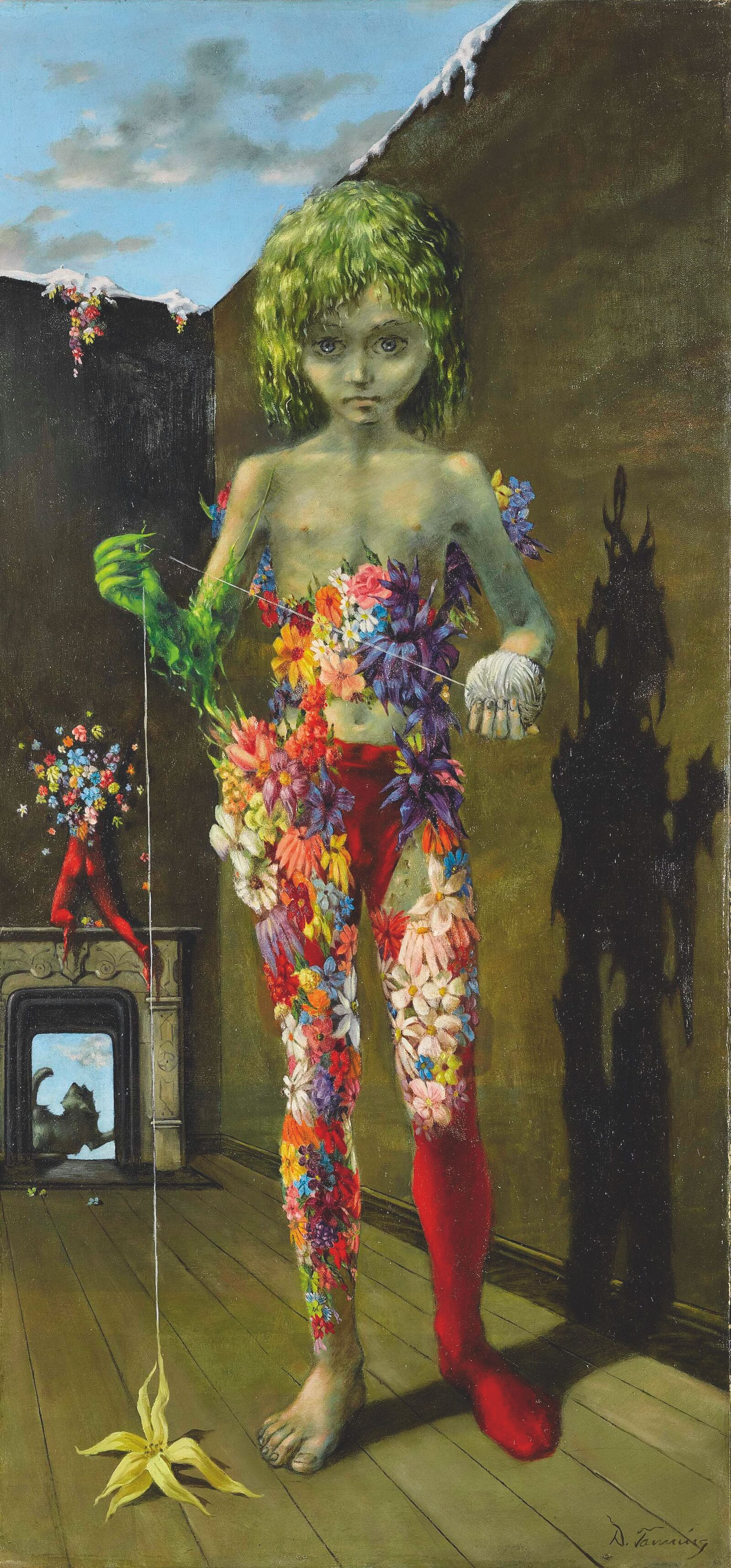

In Tanning’s work The Magic Flower Game, a young girl appears as a self-confident protagonist and looks challengingly at the viewer. In her left hand she holds a white ball of wool, from which she skilfully produces what appears to be a living flower. The girl is also in a state of vegetative transformation herself: her body consists of a patchwork of flowers, and her green hair and plant-like right arm recall the figure of a forest spirit or elf. The wool symbolizes the thread of fate that the girl courageously and actively takes into her own hand.

Dorothea Tanning: The Magic Flower Game, 1941, Private collection, South Dakota

© The Estate of Dorothea Tanning / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Dorothea Tanning’s fascination with children as protagonists in magical, fairy-tale events was intimately linked to her fascination with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1865).

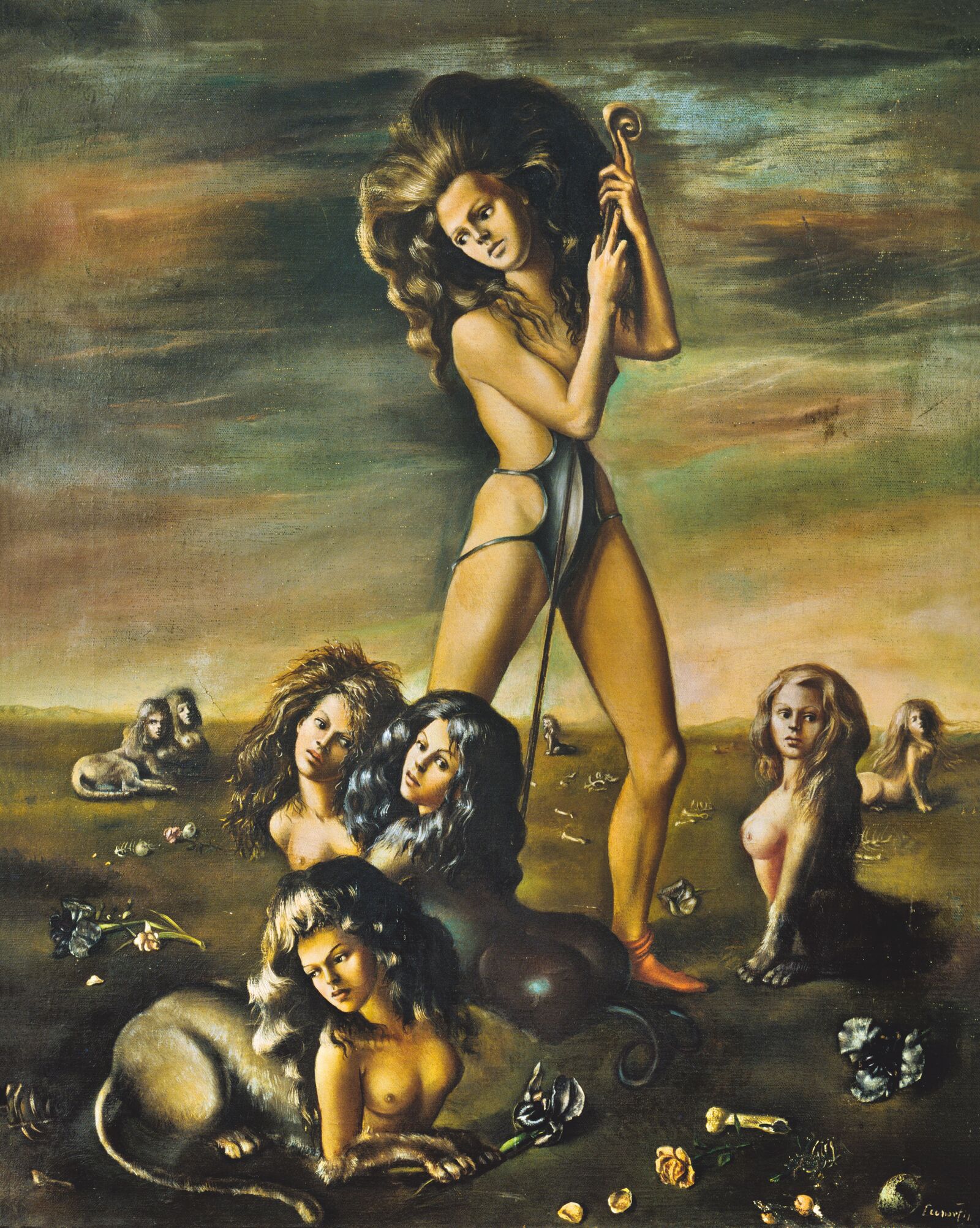

The Argentine-born painter Leonor Fini moved in the circle of the Surrealist movement from the 1930s onwards and dealt with themes of femininity and magic in her works. Powerful women or female hybrid beings dominate the motifs of her paintings. They often appear as participants in mysterious rituals or inhabitants of primeval landscapes. In Fini’s works, woman is at the center of a pantheistic universe, where she rules supreme over the eternal cycle of life and death.

Fini had grown up in Italy and was passionate about Renaissance and Mannerist art. The fine painterly execution of her paintings is a nod to Old Master models.

Here, Fini alludes to the role of maternal goddesses who rule autonomously over life and death, renewal and decay.

With her “combination of half-animal, half-human,” Fini described the sphinx as her ideal, associated with wisdom and power.

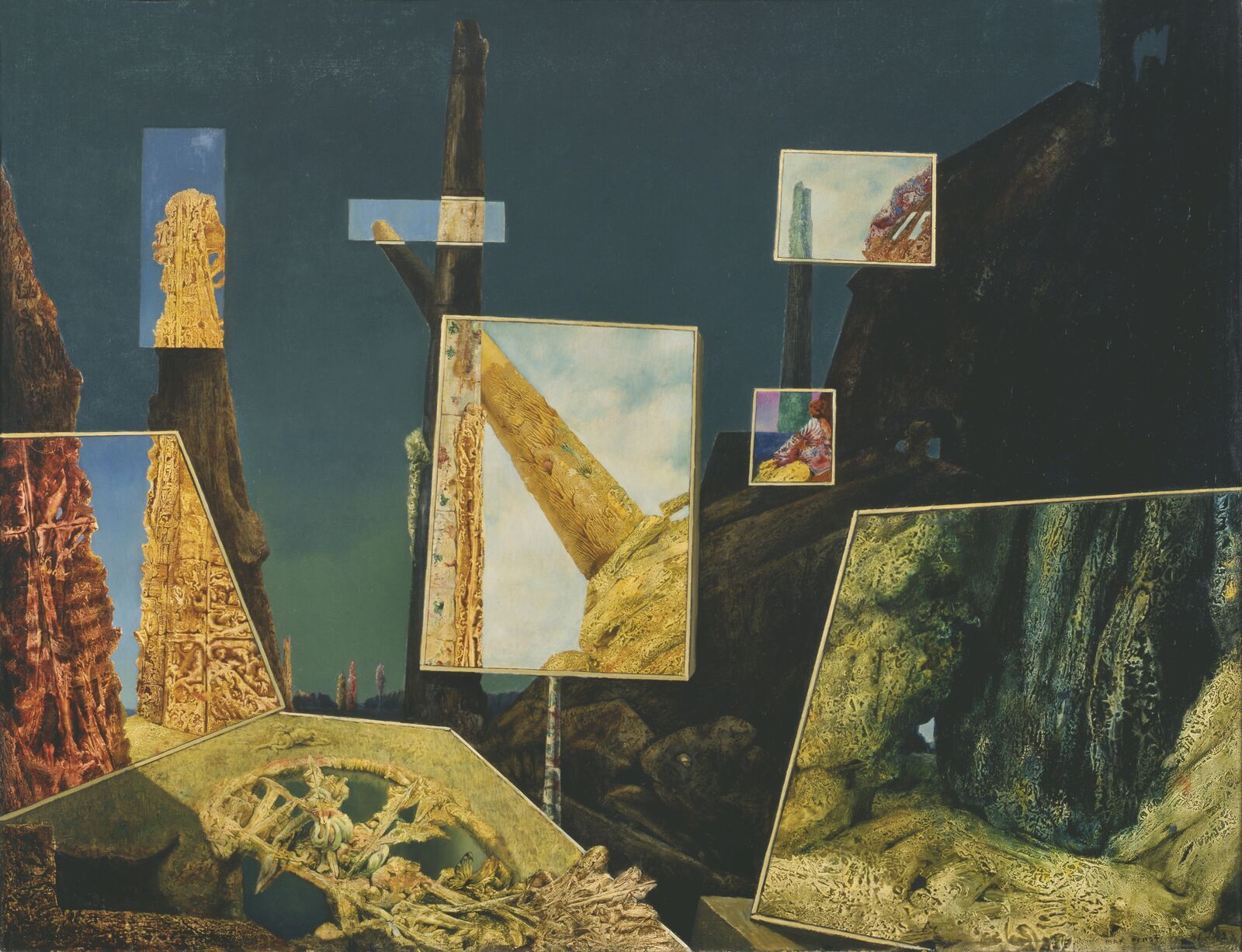

Max Ernst: The Bewildered Planet, 1942, Tel Aviv Museum of Art

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Many artists were inspired by the occult notion of endless analogies, according to which man and nature, the micro- and the macrocosm are dynamically connected. The magical idea of invisible pervading the universe became a metaphor for the unconscious and the depths of the human psyche. Many of their compositions are akin to occult landscapes, intended to visually express the elusive realms of the surreal.

Max Ernst: Day and Night, 1941-42, The Menil Collection, Houston

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: The Menil Collection, Houston, Photo: Hickey-Robertson

In Surrealism, day and night stand for reality and dream, the real and the imaginary. Max Ernst’s painting suggests the resolution of these opposites in a higher reality or “surreality.” Through the magically luminous canvases, the brightness of day penetrates the nocturnal fantasy landscape.

Already in the 1930s, the Surrealists had dealt with the threat of fascism in their paintings. They metaphorically processed the political danger emanating from National Socialist Germany in threatening fantasy landscapes.

Wolfgang Paalen: Magnetic Storms, 1938, Private collection

© Succession Wolfgang Paalen and Eva Sulzer

Image: Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco, Photo: Nicholas Pishvanov and Carter Andereck

In Wolfgang Paalen’s painting, the ghostly thunderstorm formations seem like an abstract representation of the “Wild Hunt”: fearsome spirits that, according to legend, ride on storm clouds at night. The sight of them was supposed to augur imminent war. The composition was executed in the same very year in which Hitler annexed Paalen’s Austrian homeland.

In Roberto Matta’s “psychological morphologies,” hallucinogenic structures are supposed to refer simultaneously to the depths of the human psyche and to the immeasurable vastness of the universe. With their energetic charge, these images were meant to reflect the “battlefield of feelings and ideas” that Matta associated with World War II.

Roberto Matta: Years of Fear, 1941, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, Photo: Kristopher McKay

By the early 1940s, Roberto Matta had fled to the United States. With its garish color scheme and blazing flames, Years of Fear resembles a futuristic depiction of hell. The complex spatial design reflects Matta’s training as an architect.

The US painter Kay Sage had visited the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris in 1938 and made the acquaintance of André Breton in the same year. Most of her works depict fantastic architectural scenes, often located in indefinable, futuristic-looking urban settings.

Kay Sage: Tomorrow is Never, 1955, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© The Estate of Kay Sage / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In Tomorrow Is Never, four imposing wooden scaffolds tower far above the clouds. Three of the complex lattice constructions are filled with huge linen cloths. The writhing fabrics seem like animate beings who are locked in a magical prison. The painting was created shortly after the death of Sage’s husband, the Surrealist painter Yves Tanguy. If the fabrics can be interpreted as shrouds and thus as symbols of death and transience, they also conjure up the idea of a ghostly haunting.

In many of his paintings, Yves Tanguy used his meticulous, veristic technique to make mineral, rock or cliff formations appear against gently modulated, horizonless backgrounds. The motif harkens back to Tanguy’s childhood memories of the Breton region of Finistère: his parents’ homeland, known for its dolmens and menhirs: monumental stone pillars of prehistoric times that were associated with myths, rituals, and sacrificial cults.

Tanguy was fascinated by the menhirs and dolmens of Brittany. His dreamscapes are populated by formations of minerals that seem magically animated. They illustrate the idea that natural objects are animated by ghostly forces.

In the 1940s, Tanguy made several paintings that hark back to his experience of World War II. Here, the sharp edges of glass and configurations convey a sense of aggression.

Leonora Carrington: The Pleasures of Dagobert, 1945, Private collection

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Image: Tim Nighswander/IMAGING4ART

The title refers to the Merovingian king Dagobert whose bloodline, according to legend, was supernatural. In her painting Carrington combines stylistic borrowings from late medieval art with alchemical allusions to the power of the four elements. She executed the composition using the traditional tempera technique, in which pigments are mixed with egg yolk.

In the Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1929), André Breton called for the “occultation” of his movement: the programmatic examination of occultism and magic. Nevertheless, the Surrealists rejected belief in the supernatural as such. Instead, they understood the surreal as an “absolute reality,” in which the boundary between dream and reality is magically suspended.

Everything tends to make us believe that there exists a certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imagined, past and future, the communicable and the incommunicable, high and low, cease to be perceived as contradictions. Now, search as one may one will never find any other motivating force in the activity of the Surrealists than the hope of finding and fixing this point.